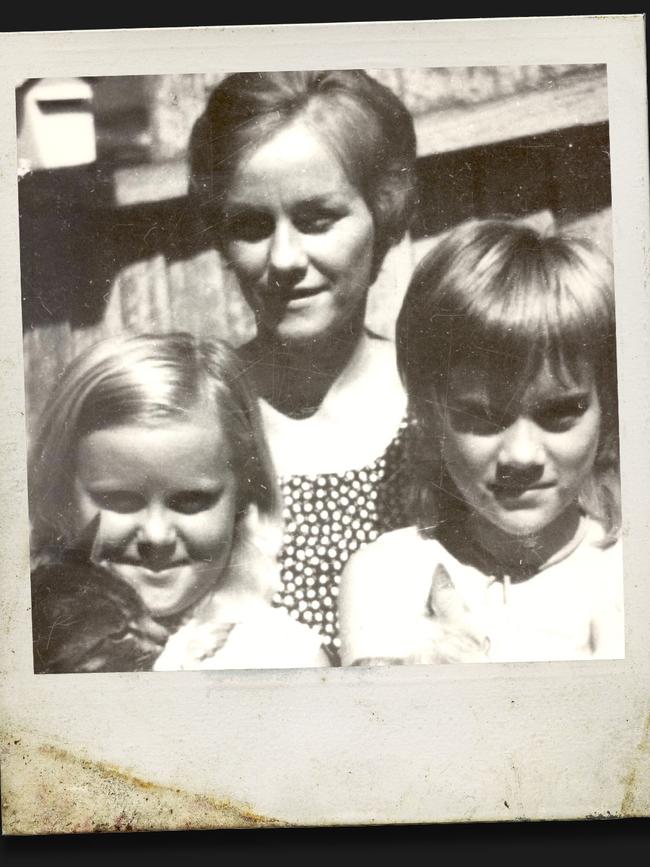

NOT a year would go by without Barbara’s brother, Graham Ogden, religiously telephoning police on January 16 – a date etched in the family’s annual calendar and as important as any birthday – and asking if there had been any developments in the case of his missing sibling and his two nieces, Vicki and Leanne.

As Graham’s nephew, Brian Ogden, would later reportedly say: “You can feel very alone when you have members of the family missing and don’t know what’s happened to them. Every time someone else goes missing, you feel for them.

CHAPTER 2: Mass murder at Whiskey Au Go Go

CHAPTER 3: The night a family vanished

CHAPTER 4: The murder of Mrs X and her children

“It’s a very dark and lonely place. It’s a part of family history that’s just blank and that’s wrong.”

Meanwhile, that run-down cottage over at 6 Dorchester St sat there virtually unchanged since Barbara and the girls vanished. There was a newish fence, installed decades later, but by and large the place had remained eerily the same since that long, wet summer of 1974.

On January 16, 2014, however, Graham Ogden would receive some news he’d always hoped for but had never anticipated.

In the lead-up to the 40th anniversary of the disappearance and presumed murders of Barbara and her two little girls, the State Crime Command’s Homicide Squad Cold Case Unit decided to revisit the case. It was, at the very least, a gesture to the McCulkin women and their family that these victims had not been forgotten. It was also an opportunity to appeal for new witnesses and information after the case had lain dormant for so long.

Then Homicide Detective Acting Superintendent Mick Dowie reportedly appealed to members of the public who might know something of the murders.

“If you are sitting at home trying to justify your silence to protect this gang, your ethics and morals are not worth considering,” Dowie said.

“The thing that goes to the heart of this is the children. It is a major threat to murder two innocent children and someone, anyone who has got information that could solve that would have to have had that weighing on their conscience for 40 years.

“These are two young girls who were murdered for nothing … what you believe happened may not be the case, you may be protecting people for all the wrong reasons.”

The public was reminded that a $250,000 reward was still active.

Dowie and his team, including Detective Sergeant Virginia Gray, then set about the laborious task of interviewing potential surviving witnesses and key players and tracking documents. They followed a similar trail to that of detectives Marshall and Menary more than 30 years earlier.

The Cold Case Unit, however, would also work in tandem with the Crime and Corruption Commission to extract as much new evidence as possible. Many witnesses were called before the CCC – with its coercive powers – throughout 2014.

This time around, too, the passage of time gave police an advantage.

One key witness eventually made a decision to tell what he knew of the era and the fate of the McCulkins, and that was former Clockwork Orange Gang member Peter Hall.

He would later explain to the court he was a different person now to the one he had been in the 1970s. That he had his own family. His evidence proved that the old adage of silence among thieves no longer applied.

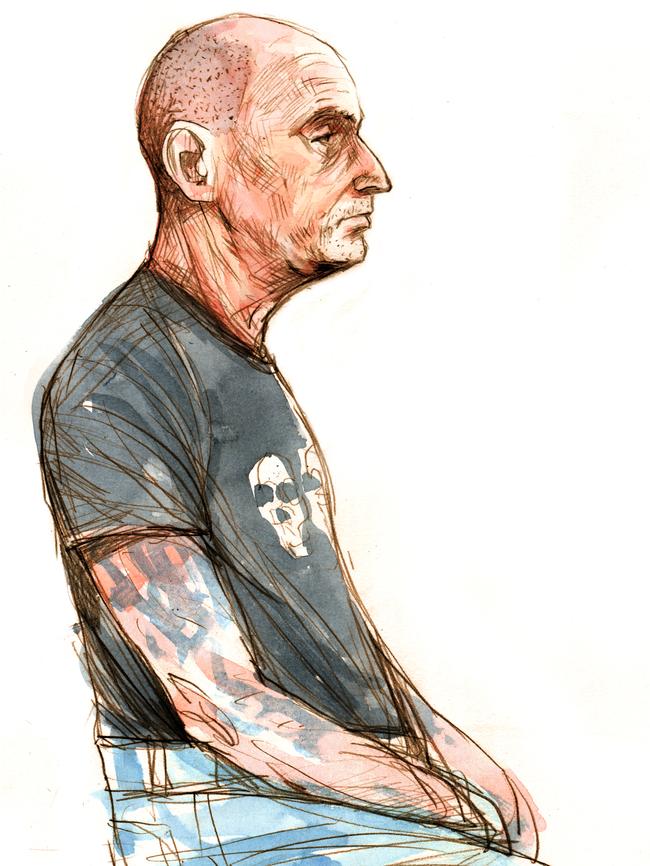

Other key witnesses followed, and in late 2014 Vincent O’Dempsey, then 76, and Garry Dubois, 67, were arrested and charged with the murders of Barbara and the two girls. The shadow of this crime had finally caught up with both men.

After both were committed for trial in late 2015, their trials were split, and Dubois appeared in Supreme Court number seven on Monday, November 7, 2016 before Justice Peter Applegarth. Dubois was charged with three counts of murder, two counts of rape and deprivation of liberty. He pleaded not guilty to all charges.

During the three-week trial, his former friend from the Clockwork Orange Gang, Peter Hall, admitted to the jury that he, Tommy Hamilton, Keith Meredith and Shorty Dubois had blown up Torinos nightclub in Brisbane in February, 1973, as part of an insurance scam. He also said that following the Torino blast the gang feared that they would be put under the spotlight following the inferno at the Whiskey Au Go Go 11 days later.

Hall said that the following year, just a couple of days after Barbara McCulkin and her daughters vanished, Shorty Dubois had allegedly confessed to being involved in the disappearance of the McCulkins. Shorty had admitted he and Vince O’Dempsey had taken them for a drive on the night of January 16, 1974, in Vince’s distinctive orange Charger to bushland near Warwick, O’Dempsey’s old home town.

Hall told the court Dubois told him that O’Dempsey had taken Barbara aside and strangled her, and then ordered him to rape one of the McCulkin girls, which he did reluctantly. Dubois then supposedly alleged that O’Dempsey killed them all.

It took the jury just 10 hours to find Dubois guilty of murdering Vicki and Leanne and of manslaughter over Barbara’s death. He was also found guilty of deprivation of liberty. His sentencing was postponed until after O’Dempsey’s trial, slated for 2017.

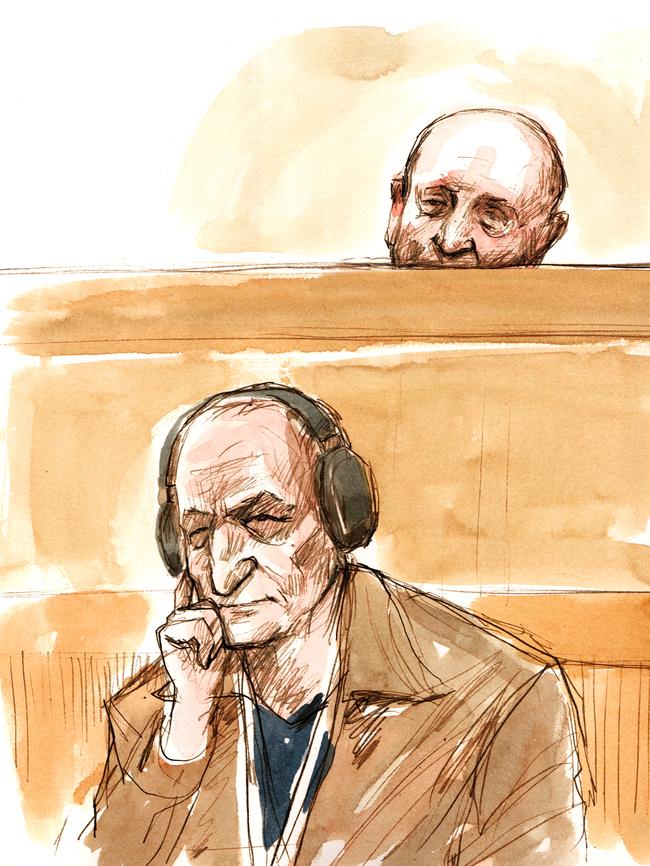

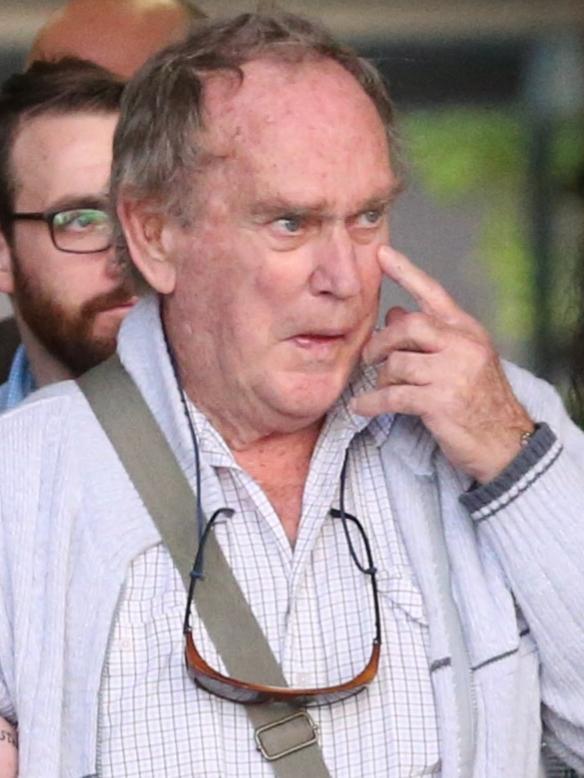

At 10.02am on Tuesday, May 2, this year, O’Dempsey was led into the dock for the start of his trial, also before Justice Applegarth. He stood charged with three counts of murder and one of deprivation of liberty.

At his committal and in other court appearances prior to the trial, O’Dempsey appeared in his customary leather jacket, open-necked shirt and thongs.

For his trial, he was attired in a charcoal grey suit, a white or blue business shirt with a tie and slip on black shoes. He walked to and from the dock with a slight pigeon-toed shuffle, just as Billy McCulkin had described his gait to police all those years ago.

The prosecutor was David Meredith. O’Dempsey was represented by Tony Glynn, QC.

O’Dempsey also pleaded not guilty to all charges.

At 12.03pm on that first day, Meredith began his outline of the prosecution’s case, and opened with the torching of Torinos on February 25, 1973, followed by the massacre at the Whiskey Au Go Go on March 8 of that year.

It was clear from the outset that these two events – the fires – would remain front and centre throughout O’Dempsey’s trial, and indeed these crimes were mentioned on almost every day of the hearings. Meredith also outlined the connections between a volley of criminals back in the 1960s and ‘70s in Brisbane, and that Barbara’s knowledge of who was responsible for the Whiskey atrocity may have been reason enough to keep her quiet.

“It is not suggested at all that Billy or Barbara McCulkin had anything to do with the Whiskey fire but their knowledge or claimed knowledge may be relevant to her death,” Meredith told the jury.

“Also, it is not suggested that Garry Dubois had anything to do with the Whiskey fire but the suspected connection between it and the Torino fire would provide a motive for Dubois and O’Dempsey (as a friend of Dubois to) keep Barbara McCulkin quiet.

“It may not sound a sufficient motive or even a sensible one, but there never is for murder.”

More than 60 witnesses were called, including Hall, family members, neighbours, work colleagues of Barbara, school friends of the McCulkin girls, former detectives, ex-wives and lovers of O’Dempsey and even a prison inmate who earlier this year had been in the same unit as the accused at the Arthur Gorrie Correctional Centre, outside Brisbane.

The inmate, with the help of police, secretly tape recorded O’Dempsey making threats to trial witnesses and giving up certain admissions about the death of Barbara McCulkin.

O’Dempsey allegedly told the inmate that Barbara McCulkin had to be dealt with, and that in the past when you were paid to do a job, you did the job.

It was a trial that witnessed some unusual disruptions, the details of which were suppressed by Justice Applegarth. In addition, court security measures were increased with the arrival of certain witnesses.

But throughout, O’Dempsey remained impassive behind the green-tinged glass of the dock. Occasionally he waved and joked with members of his family who sat in the public gallery immediately behind him.

Across the aisle, behind the media seats in the courtroom, Barbara’s brother Graham Ogden and his family turned up each and every day for the trial. They had waited for more than half a lifetime to see justice for Barbara and the girls, and not a minute of the trial would transpire without their attendance.

Outside the court, too, the two police officers most responsible for resurrecting this extraordinary case – Gray and Dowie – came and went, milling with fellow police officers, saying “G’day” to the Ogdens, taking notes in court.

As Meredith underlined in his opening address: “This is an old case.”

And it was. The evidence of many witnesses, since deceased, were offered in the way of statements to police and records of interviews produced in the long history of this case. And some elderly witnesses shuffled in and out of the witness stand, their hearing challenged in the cavernous courtroom.

The jury too was taken back to a Brisbane of the early 1970s, to Valiant Chargers and black and white television, photographs of pop star Elton John on the wall of one of the McCulkin girls’ rooms and records by Donny Osmond, and the great Brisbane floods of 1974.

It was a case often steeped in nostalgia. But this was no reverie.

This was about the cold-blooded murder of a defenceless young mother and her two children. This was about three lives being senselessly deprived of a future.

Nothing was more chilling than the sequence of black and white photographs taken by police inside the abandoned house at 6 Dorchester Street shortly after the disappearances, and tendered to the court as evidence about halfway through the trial.

There was the hallway into the loungeroom of the house. The cracked linoleum on the floors. The box television with a small arrangement of plastic flowers on top. The dim kitchen and the chipped kitchen table. The dresser in Barbara’s room again bearing a narrow vase of flowers and crowded with cosmetics, and the door with a white bathrobe hanging from a hook behind it.

One of the girls’ rooms, the single bed made and with two stuffed dolls resting on their backs, their heads on the pillow. The spare room cluttered with a large old wardrobe and boxes of discarded bags and toys, and on the wall a poster for the Walt Disney children’s movie Million Dollar Duck. Another of the girls’ rooms, with a pair of roller-skates by the door.

The sparse loungeroom with the well-used couches and the sideboard with glassware on display and framed photographs of Vicki and Leanne as babies.

And finally the sewing table in the loungeroom, with a child’s dress still caught under the needle. The chair that Barbara used is pushed back slightly from the table and at an angle. It was not impossible to imagine her last moments in the house, half-standing and moving that chair back just enough to release her slight frame from the sewing table. An angle that, in the picture, promised she would return, slip into that space again, pull the chair up once more and get back to her sewing.

The photos showed no blood. No violence or disturbance. It was not your typical crime scene.

What the pictures recorded was the precise moment of a great loss. What gave them their eerie power was the stillness of what was there, which just served to underline the profound absence of what wasn’t there, and that was the life of the McCulkin women.

With Dubois already behind bars, O’Dempsey – the amateur boxer, ballistics expert, pimp, thief, gunman and murderer of Warwick, Queensland – was also finally found guilty of the deaths of Barbara May McCulkin, Vicki Maree McCulkin and Barbara Leanne McCulkin.

According to evidence given during the trials, O’Dempsey had once called his little sidekick, Shorty, “nothing but a rapist”.

But O’Dempsey’s own ex-fiance, Kerri Scully, had offered her own assessment of Vince. She told the court he had confessed to her he had committed 33 murders.

“If you try and arrest him he will try and kill as many of you as he can,” she told the committal hearing of both the accused in late 2015.

“There are no real gangsters anymore but back in those (Vince’s) days there were – he was at the top of the top.

“His nickname is the ‘angel of death’.”

After decades of speculation and fear, one thing finally became crystal clear. These two old gangsters would die in prison.

EPILOGUE

THIS is what could, and should, have been. Today, Barbara McCulkin would be 77 years old, and in her retirement, after a happy second marriage following the collapse of her first to Billy McCulkin all those years ago, her days would be filled with looking after her precious cats, sewing, and visits from her grandchildren.

They’re teenagers and older now, the offspring of their respective mothers, Vicki, 56, and Leanne, 54, but it’s a close-knit family.

Sometimes Vicki and Leanne might take their elderly mother for a drive around the Brisbane that Barbara knew from her earlier years in the city.

They might pass the site of the Milky Way snack shop in Adelaide St where Barbara worked in the early 1970s, now one of numerous office towers in the CBD.

A return to their previous home at 6 Dorchester St, still as ramshackle and haunted as it was in their day, filled with so many bad memories of their violent husband and father, Billy, and the procession of his gangster mates in and out – Vince, Shorty, Tommy, Johnny and the rest of them – would probably not be on the cards.

As a counterpoint, they might go and see the old Red Hill Skate Arena in Enoggera Terrace, now just a charred ruin after a fire in the early 2000s, but for so long the epicentre of happy childhood moments for the McCulkin girls.

Sitting outside the ruined skate rink, Vicki and Leanne would remember coming there every Saturday night with Barbara when they were carefree children. Here was a place of laughter and fun, a sanctuary away from the squalor and violence and hate of Dorchester St.

The girls might recall zooming round and round the concrete rink, one lap after the other, with Barbara quietly watching on. In the joyful giddiness of skating, there she was, their mother, the only solid, reliable anchor in their young lives.

But this is not how it is or how it was ever going to be.

Two cheap hoods with a propensity for rape and violence made sure of that on a humid night in January, 1974.

The brutal, callous, cowardly murders of Barbara and the girls had been, for almost half a century, a black hole in the criminal history of this city, a void that we blanched at peering into for fear of what we might see.

Over years, then decades, this mystery fossilised, refusing to yield its secrets. So much so that it was creeping towards that rare and frightfully exclusive category of crime – the perfect murders.

But new evidence stemming from a brilliant police investigation, coupled with a sterling prosecution, changed all that.

It is impossible to gauge the sort of wreckage a crime of this magnitude and longevity leaves in its wake. There is the impact to the immediate family and friends at the time. Then as they grow old, the deaths ripple onward and outward through to the next generation, and the next. That is the horrid reality of these murders. The shadows grow longer, darker and colder as each year clicks over. Yet Barbara and the girls remain unchanged, in photographs and in memory.

Today, thanks to the unwavering faith of the McCulkin family and relatives and the remarkable work of not just contemporary detectives who finally brought this case to a close, but that of their predecessors in the Queensland police force, the McCulkin murder case can finally be taken off the books.

The chief investigators this time around were either toddlers or not even born when this crime took place. Some of them have their own children now, some the same age as the McCulkin girls when they vanished off the face of the earth.

The investigators, though, and the family of the victims, know too well that there will always be questions that the trials never answered, and that the loss never ends.

This case has haunted generations of police, ordinary Queenslanders, and even criminal associates of the accused who have carried their respective burdens for more than 40 years.

The biggest question remains – where are Barbara and the girls?

Until they’re brought home to their family, this case will never been closed.

CHAPTER 2: Mass murder at Whiskey Au Go Go

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As we move into winter what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As we move into winter what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.