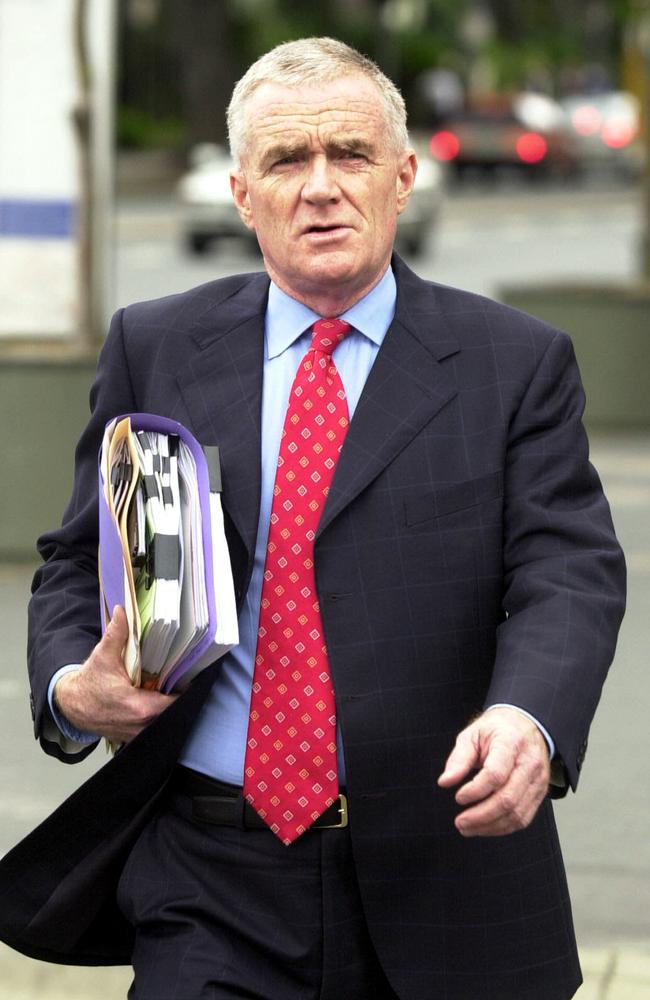

If ever Queensland had a legal lion it would have to be Terry O’Gorman and, even as this lion enters his winter, his roar remains undiminished.

For a lengthy period there in the late 20th Century O’Gorman represented a sort of political book end in this state.

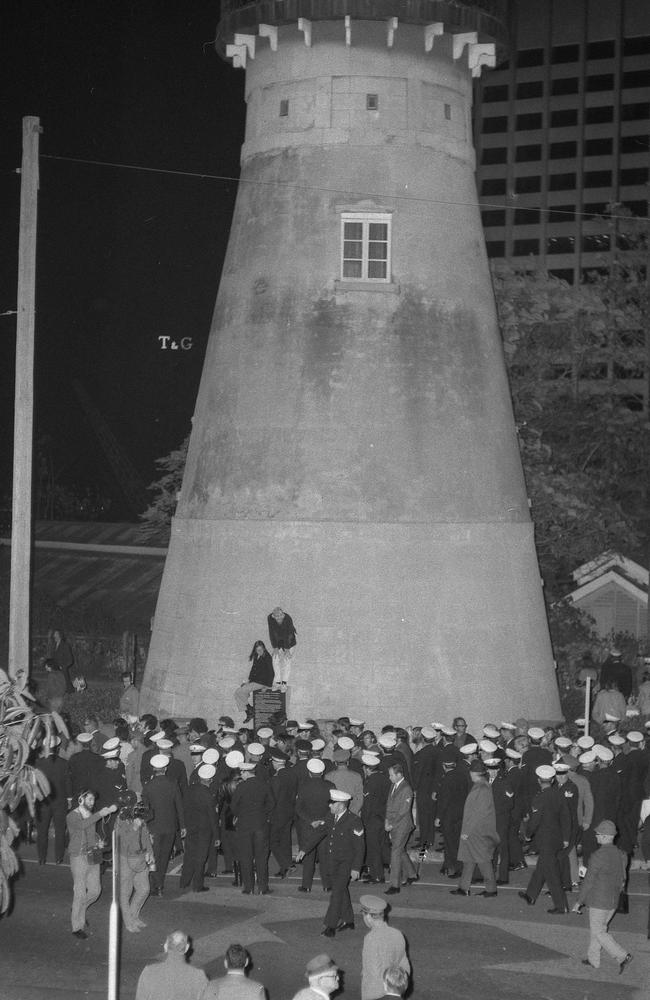

At the right side of the spectrum was Premier Sir Joh Bjelke Petersen, loudly declaring we couldn’t march in the streets.

At the left side was O’Gorman, even more loudly declaring that we could.

With the benefit of hindsight, O’Gorman can be declared the definitive winner of that contest as well as the victor of numerous other clashes with various courtroom antagonists strewn across the decades.

He’s devoted himself to one simple theme encapsulated in the raison d’etre of the Queensland Council for Civil Liberties, a state institution he has been involved with almost since its inception — “defend and preserve civil liberties.’’

It’s a testament to his status that the newly retired 73-year-old received his Order for Australia for services to the legal profession 34 years ago.

He’s also the recipient of the Law Society’s Outstanding Accredited Specialist Award, the Queensland Law Society’s President’s Medal and almost certainly a host of other accolades he hasn’t bothered telling me about as he chugs a Byron Bay Premium lager while digging into a steak at the Breakfast Creek Hotel – a pub he loves largely because he can walk home from it.

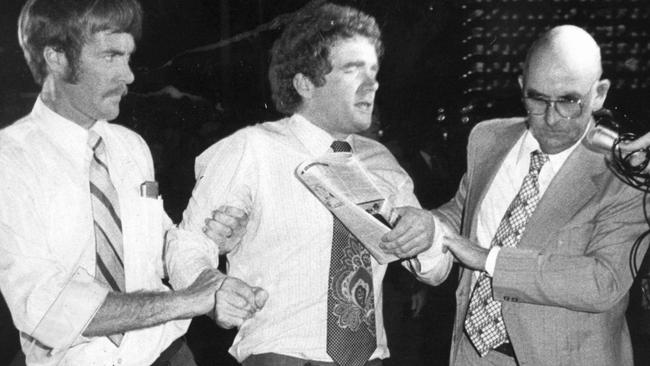

But don’t for a moment think O’Gorman, who played a pivotal role in the corruption-busting Fitzgerald inquiry with his celebrated cross examination of Sir Joh, is some political cliche stuck in a leftist groove.

“Believe me, I have had plenty of arguments with the left,’’ he reassures me dryly.

One, which he will pursue even in what might be better termed his “semi retirement,’’ is the rights of defendants in the courtroom, particularly those in rape cases.

The right to silence and the duty of the prosecution to disclose all evidence in its possession relevant to the case (including evidence that may assist the defence) are now in jeopardy, he believes.

That puts him at odds with large tracts of the political left which, in the wake of the Me Too movement, are calling for law reform in rape cases.

But criticism doesn’t appear to have ever troubled him.

“The pendulum has swung too far,’’ he declares in that distinctive voice, polished by decades of courtroom clashes, which brooks no argument.

He grew up in Nundah with 15 siblings in a family which seems to have been possessed by some sort of genetic seam of gold.

His own worldly success is challenged by various brothers and sisters. One of them headed the Queensland Police Union, another reached a senior position in the Australian Taxation Office, another went to the law and became a QC (unlike Terry) yet another retired as an Assistant Police Commissioner, and three more became nuns.

He credits his mum and dad as worthy parents.

“It was far from a privileged upbringing, but it was a very solid Catholic upbringing,’’ he says.

He’s more than willing to give a nod to the Catholic Church which he had largely walked away from by his early 20s, partly because of support from the pulpit for Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, but which gave him and his siblings the intellectual tools to take on the wider world.

”They provided a first-class education,’’ he says of St Patrick’s College Shorncliffe where he was school captain, and where his academic brilliance led to the scholarship which enabled him to attend university and study law.

One teacher, knowing he was not from a wealthy family, would buy “The Bulletin’’ (a then popular political magazine) and hand it over to O’Gorman each week after he had finished reading it, telling the boy to consult him if he had any questions about the articles.

His vocation regarding civil liberties began early in his career.

Soon after joining the Aboriginal Legal Service in Brisbane in 1976 it became blatantly obvious to him that many of his clients were being “fitted up’’ for crimes, signing confessions they had never made.

“That was in an era where the ‘verbal’ was flourishing,’’ he recalls of pre-Fitzgerald Queensland.

A number of senior Brisbane barristers had been trying to do something about it for years, getting nowhere.

O’Gorman, whose counter offensive against the outrage once involved smuggling his own tape recorder wrapped in newspaper into the Brisbane Valley Police Station, became determined to call police out, going above and beyond the call of duty to do so.

When he was asked by Derek Fielding, then president of the QCCL, to represent a group of “hippies’’ living in Cedar Bay in the Far North and being harassed by police, he trekked through wilderness to reach his clients.

“I was wearing a lime green safari suit that my mother had given me as a present when I graduated university,’’ he recalls.

When he arrived he was greeted by a group of naked women on a beach and so, adopting the “when in Rome’’ philosophy, discarded the suit and took statements from his clients in his underwear.

It may be redundant to mention he has a good sense of humour, but despite the gravity of his work he clearly relishes the comic side of life.

There has to be a long-running O’Gorman family joke in the fact that Queensland police, in the midst of a 70s street protest, arrested his cop brother, who was monitoring the protest in plain clothes.

They threw brother “Bluey’’ into the paddy wagon thinking he was “Terry.’’

“A case of mistaken identity,’’ twinkles O’Gorman, still delighted by the fracas.

Yet there’s little humour in what he sees as a dramatic erosion of rights in our court rooms, especially regarding defendants’ rights in rape trials.

While he acknowledges the crime as one of the most serious in the criminal code, he doesn’t believe it is one which requires the abandonment of hundreds of years of legal precedent, especially in the realm of the right to silence.

He often finds himself in agreement with journalist Janet Albrechtsen’s columnists with the News Corp owned Australian newspaper, who regularly writes about the dangers of eroding defendants’ rights in rape cases.

O’Gorman says judges presiding over some rape cases where the evidence is thin can advise a prosecutor during a trial to seek advice from their superior about abandoning the case.

“They (the prosecution) come back and say they have been directed to continue,’’ O’Gorman says.

“Why? Fear of the publicity of the complainant complaining to the media …’’

Ultimately, he wants to see the establishment of a National Criminal Cases Review Commission dealing with miscarriages of justice.

That pursuit is not specifically prompted by his concerns about rape trials, but reflects his belief that the absence of such a body is a glaring omission in our justice system.

Review commissions already exist in Commonwealth countries like Canada and New Zealand after the English set one up decades ago, prompted by irregularities in the arrest and incarceration of Irish nationals accused of terrorism.

Up to 60 per cent of the cases the English Commission come down on the side of accused.

The idea has been on the agenda of the Standing Council of Attorneys-General for years but O’Gorman sees no movement on it, partly because there are few political points in defending the rights of the falsely accused.

As he says, few people care about victims of a miscarriage of justice until they themselves, or one of their loved ones, are falsely accused.

At the moment you can appeal a conviction, and if you lose you can go to the High Court, but only if the High Court gives you leave to appeal.

“And that rarely happens.’’

Two Eye Fillets, one side of greens and two Byron Bay schooners dispatched, O’Gorman is going to walk it off with a stroll to his home nearby.

There’s flies aplenty in the Spanish Garden restaurant, but that’s not the fault of the pub, just part and parcel of a Queensland summer.

It’s been a great lunch — nine out of ten.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Tragedies, triumphs … and that ‘Mr Potato Head’ moment

With a lifetime of tragedies behind her, the woman who finally ousted Peter Dutton on her third attempt knows a thing or two about perseverance. Here, she tells her story, and exactly what happened with that ill-fated fundraiser.

Ten seconds of glory: Inside Queenslander’s journey to sprint perfection

Lachlan Kennedy joined an exclusive club when he became just the second Australian to break 10 seconds in the 100m at the national championships. Re-live our interview with the sprint star and see how he got to this point.