Lachlan Kennedy joined an exclusive club when he became just the second Australian to break 10 seconds in the 100m at the national championships. Re-live our interview with the sprint star and see how he got to this point.

Last out on the track is Gout Gout, the 17-year-old running sensation who, it’s fair to say, most of the spectators at this Maurie Plant athletics meet are here to see, and almost all expect to win.

Except, perhaps, those who’ve been following athletics closely in the past couple of years – and one bloke who happens to be sitting within earshot of another sprinter’s coach.

“Lachlan Kennedy is going to win this,” the man says to his friend beside him.

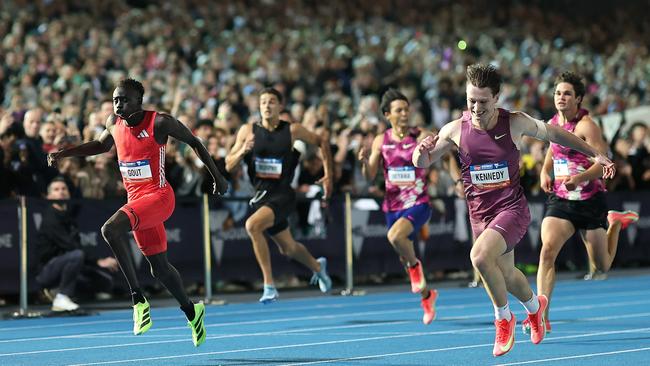

And, exactly 20.26 seconds after the start, Kennedy, 21, does just that, in what sports pundits will later call the “upset of the decade”.

And while it might have seemed like Kennedy came out of nowhere when he came out of the blocks, the truth is, this remarkable young man who likes to be called “Lachie” – “don’t call me Lachlan, it makes me feel like I’m in trouble with my mum” – has been training consistently and steadily improving his personal best times for the past four to five years. He also won silver in the 60m at the World Athletics Indoor Championships in Nanjing on March 21.

It was his coach, Andrew Iselin, who overheard that comment in the stands, and who watched his young charge do what everyone said couldn’t be done.

He’d also watched Kennedy, a former rugby union player who switched to athletics in Year 11 at Brisbane’s St Joseph’s College Gregory Terrace, also win the 100m earlier that day. Kennedy - good natured and good humoured - says that while he loved playing footy, he realised pretty quickly that running suited his mindset, body, and “I also enjoyed the idea of not getting hit”.

“I was a very competitive person by nature, but that side of me didn’t manifest itself in rugby because it’s a team sport so it’s a lot harder to stand out,” Kennedy says.

“Especially the position I played, I’d just stay on the wing, I would get my hands on the ball four or five times a game, but I’d score most of the time,” he grins.

“One day, one of our coaches at school – Gaz – he’s a legend, big shout out to Gaz – said to try running, because he’d noticed I was fast.”

How fast? In his first open time trial, Kennedy, then 17, recorded the fastest time on track. At his first meet, the 100m in the Greater Public Schools (GPS) track and field competition he came third in an elite field of runners.

“I was pretty shocked actually,” he says. Since then he has proved ‘Gaz’s’ (real name Gary Munday) instinct right. And by the way, that shout-out to Munday is very much Kennedy’s style.

Friendly, polite and respectful, he’s a weapon on the track and a cheerleader off it. He calls his mother Rachel “an absolute legend”, his father, Simon “a big dog”, his coach Iselin “a trouper”, and fellow Queenslander Gout Gout? Well, he’s, in Kennedy speak, “the G Man”. And according to Kennedy, the G Man is “deserving of all respect”.

“The G Man? That’s my boy, hell yeah,” Kennedy smiles widely.

“I mean he’s obviously four years younger than me, so we haven’t spent too much time together. But he is such a sweet person. Such a good bloke. Every single interaction I’ve had with him has been positive.

“I can’t help but smile when I’m around him.”

All that bonhomie doesn’t mean Kennedy doesn’t want to beat him, though. He really, really does.

And despite the shockwaves at Maurie Plant he has bested Gout before, at smaller, so-called “shield” meets, the weekly/fortnightly events organised by Queensland Athletics. But not, he grins, for a while.

“In my first big race last year (the World Under 20 Championships) Gout broke the current Australian record in the 200m, and he absolutely whooped me. I had him around the bend, but then he just ran me down.”

The Maurie Plant meet was the first time Kennedy’s raced Gout Gout since the worlds, and it was a race so close – like all these elite sprints are – “I could hear the G Man coming”.

“I could hear him closing, I mean his foot is so light but yeah, I could hear him breathing. He closes like nobody else.”

Except this time, he couldn’t close on Kennedy who raced a PB, 0.7 of a second faster than his previous best of 20.9.

“I was shocked, it was pure emotion. 0.7 seconds is crazy. Crazy, right? That just doesn’t happen. It’s unheard of, especially at this level.”

Except it did happen, and when it counted.

And while Gout Gout’s coach Di Sheppard later said that her superstar sprinter was “angry” at Kennedy’s boilover victory, Sheppard made it clear her runner’s disappointment was directed at himself, not the man who stole his thunder.

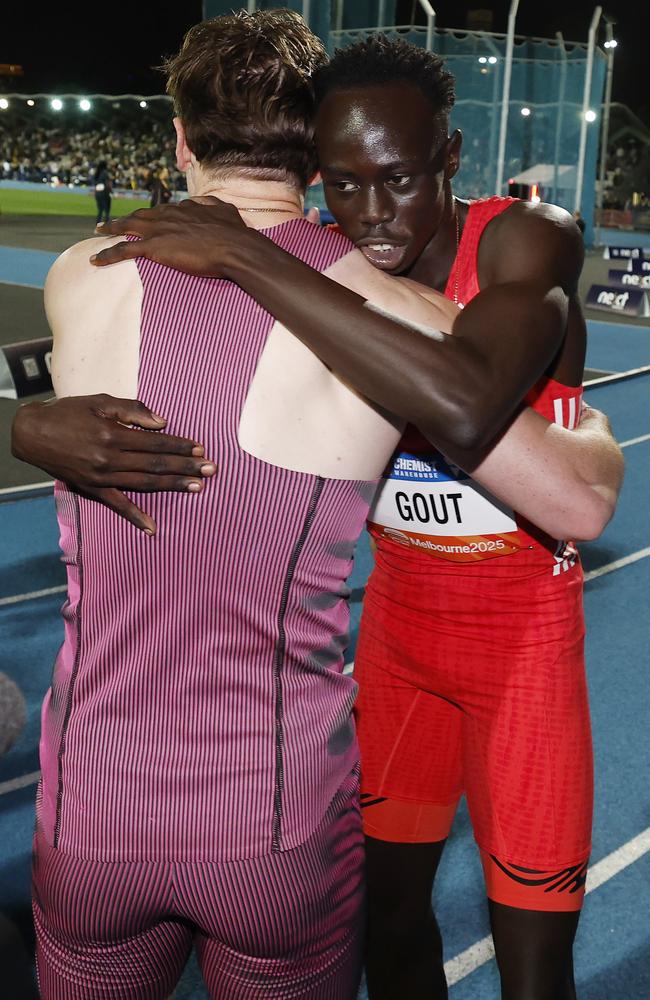

The vision of the two sprinters embracing at the finish line is now an image for the ages, and, Kennedy says, a true depiction of their relationship.

“We hugged it out, of course,” Kennedy says.

“I make sure after all my races I always take a bit of effort to make sure to tell everyone ‘good race’. I went to Calab first, obviously because that’s my boy (third-placed Calab Law, another Queensland rising star, also trains under Iselin) and then I went to Gout. I don’t know if he’d be upset or disappointed, but he was fine, he was chilling. I just went up to him and I said, ‘Hey, great race man’ and he’s like ‘Hey, man, you killed it’, and I was like ‘Thank you bro, appreciate it - and I’ll see you in Perth’.”

And when the two runners – and Law – do face off again at tomorrow’s 200m at the Australian Athletics Championships in Perth, no doubt it will once again be a full house. Athletics is enjoying a spike (pun intended) in popularity at the moment, and much of that can be attributed to Gout Gout, whose blistering times have seen him compared to Usain Bolt. And while some might grumble at most of the spotlight shining on “the G Man”, Kennedy is not among them.

“What is that saying? A rising tide lifts all the boats. Well Gout is that tide. He’s killing it. He’s the fastest 16-year-old ever and he’s bringing so many people to our sport,” he says.

“We had 1.2 million people watching our race worldwide. That’s good for everyone.

“And how he handles all the attention, I just can’t imagine doing all that, it would just drive me insane, even what I’ve been doing in the last couple of weeks since the race … I’ve had a taste of some of that media attention and I can see how it might feel like a lot.

“But he gets it all the time, and he is in Year 12, the toughest year of his life, the hardest year of school. I just have so much respect for him, it’s all respect. That’s real resilience. I mean he’s a good kid, no, he’s a great kid.”

The same could be said of Kennedy, although at 21, he’s no more a ‘kid”, so a better description would be a good man.

And the same resilience he attributes to his rival, could also be given to Kennedy, who has Type 1 diabetes. Diagnosed at 15, he – quite literally – has not let it slow him down.

“I think I was about to turn 16 when I was diagnosed,” he remembers.

“I was losing a lot of weight, I was going to the bathroom like 20 times a day – I was like that’s not normal – I lost a heap of weight, I was thirsty all the time, and my mum and dad, well, we put two and two together. Mum’s dad, my grandad has it, and so does my younger sister Milly. I was a bit upset at first, but I was like, ‘okay, all right, let’s deal with it’, and my parents were devastated at first but then they did the same. I mean my grandad is still kicking. He’s like 85 and the regime and the treatment is so much better than it once was.”

Kennedy rolls up the sleeve of his jacket to show a small disc attached to his arm.

“So I’ve got the CGM here (continuous glucose monitor) on my arm that measures my levels and then I’ve got the pump (Kennedy lifts his shirt and points to his stomach) here that gives me insulin,” he says. “I change the one on my arm every 10 days, and I change my pump site every four days. Years ago it used to be like 10 to 15 needles a day and now it’s like maybe five needles a fortnight.”

He gives a huge smile.

“I’d like other young people to know that getting a diagnosis doesn’t mean the end of anything. It’s very manageable.”

Then he adds the mantra of seemingly every young person today, whether they’re serving you a coffee at a cafe or dealing with diabetes –“It’s all good.”

Kennedy credits his parents Rachel and Simon for his positive attitude. Also his work ethic. And his determination. And just about everything else. “I was born in London but we moved to Brissy when I was really young, we have always lived on the southside.

“My mum is an accountant and my dad is the acting CEO of a property management company. He’s a big dog. He’s pretty cool, my dad. He’s the hardest working person I know, he’s taught me how what you get out of life depends what you put into it,’’ he says.

“And my mum … what can I say? My mum is a legend. She has always put me, and my younger brother (Henry, 16 and Emily, known as Milly, 18) ahead of anything else. Ahead of herself. All the time.

“As soon as I got diagnosed with diabetes, she was just on to it ... my parents are really proud of me, but all they really care about is that all their kids are happy and healthy.”

There’s another person who really cares that Kennedy, who is also studying a Bachelor of Engineering/Commerce at the University of Queensland, is happy and healthy – Iselin. Previously coached by Russel Hansen (another person afforded “legend” status by Kennedy), and who was based at UQ, Kennedy has been with Iselin since late 2023.

In 2024 Iselin took him all the way to the Paris Olympics and a place in the men’s 4x100 relay team.

An Indigenous mentor and tutor at Brisbane’s Nudgee College and coach at the Mayne Harriers Club in Windsor, Iselin knows all about the power of hard work and resilience.

At just 17 years old, he suffered a stroke, cutting his own promising athletics career short. Caused by a bad fall on the football field and a later, slow-forming blood clot, Iselin had to learn to crawl, and walk again, eventually competing as a runner as an athlete with a disability.

Better placed than most in the art of getting back up again after a fall, Iselin’s motto is to “coach the person not the athlete”.

“If I’ve done my job right,” Iselin says, “I want to help them (his athletes) become better people as opposed to them hitting goals performance wise. I want my athletes to respect everyone and treat everyone how they want to be treated. I want them to give back to society as much as they can, I want them to give more than they take.”

Does he also want them to win? Iselin chuckles. “Absolutely.”

For his part, Kennedy says Iselin “lets his athletes steer their own path”.

“He’s not the type of guy who is in your face, he’s not going to force you to do anything,” he says. “What Andrew has really helped me with is to enjoy this. To just keep a level head and keep a relaxed demeanor, to have fun, and enjoy it all. I have the utmost respect for him. He’s had to overcome a fair bit and he’s shown us all how to do it.”

The two also enjoy healthy banter. Asked to describe his runner, Iselin offers “goofy white boy”, and says that lately his athletes have been teasing him about putting on “a little weight around my middle”.

“Don’t listen to him”, Kennedy interjects, “he gives as good as he gets.” They laugh, and Kennedy says Iselin has indeed helped him to become “a better man”.

“He’s just a trouper. He’s been through a bit himself and comes up smiling.”

Iselin has taught his athletes, Kennedy says to “just do your best, try to enjoy every moment – and run as fast as you can.”

Shout-out to Lachlan Kennedy. Also a trouper. Also resilient. Also a real contender. It’s all good.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Forgotten Aussie TV star’s sad personal battle

He was a fixture of Aussie television but behind the laughter lay a spiralling battle.

Grandmas’ surprise wedding role for bride and groom

What started as a simple dance request became an extraordinary love story spanning two countries.