Then and now: How Brisbane CBD’s skyline has changed in the past 100 years

Brisbane CBD’s skyline has changed significantly over the past century with the commanding presence of various iconic buildings. See photos from the archives of Brisbane’s evolution.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Brisbane’s skyline has evolved drastically over the past 100 years and it is set to change again as the city barrels full steam toward the 2032 Olympics.

From City Hall’s commanding presence in the 1930s and the Story Bridge’s arrival in the 1940s to the making of South Bank after Expo 88, the face of Brisbane has evolved as iconic new buildings popped up.

Now experts believe the city’s image and skyline will noticeably change again ahead of the Olympics, driven by an architectural renaissance.

University of Queensland’s School of Architecture deputy head Dr Antony Moulis said the Games would “clearly fuel” the momentum of the city’s architectural development, with ideas of sustainability and urban resilience at the forefront.

We take a look back at the buildings and projects since the 1920s which have shaped what Brisbane looks like today.

SCROLL DOWN TO SEE PHOTOS OF HOW THE SKYLINE HAS CHANGED EACH DECADE

THE CHANGING FACE OF BRISBANE’S SKYLINE

Brisbane’s evolution over the past 100 years has been driven by the city’s growth and subtropical climate, heralding the arrival of skilled architects and hoards of people.

University of Queensland Emeritus Professor Peter Spearritt said one of the most dominant moments in terms of Brisbane’s skyline was the opening of City Hall in 1930. It remained a dominant part of the vista until the 1980s.

“When construction first began, Brisbane was just one of 20 municipalities, but in 1924 the state parliament voted for just one huge metropolitan council, the only capital city in Australia to have such a body,” Professor Spearritt said.

“The City Hall, symbolic heart of Brisbane, opened in 1930, and towered over the rest of the city. But when building height limits were lifted it became overlooked by high rise office and later apartment blocks, and has lost much of its majesty.

“Its clock tower is visible from both sides of the river … it really was the most notable thing in the skyline until the Story Bridge opened in 1940.”

The Story Bridge was constructed in July 1940, connecting the northern and southern suburbs of Brisbane, and is the longest cantilever bridge in the country.

Professor Spearritt said not much by way of prominent architecture construction occurred from then on until the development of the first high-rise and mixed-use residential development, Torbreck, built between 1958 to 1960.

“And of course, it wasn't in the CBD. It was on Highgate Hill,” Professor Spearritt said.

“But it is interesting … because briefly it [was] the tallest building in Australia.”

Professor Spearritt said Brisbane’s timber and tin houses, mostly built between the 1870s and the 1960s, remained the city’s most important architectural and heritage attribute.

“The Brisbane City Council, over successive administrations, can be proud of its efforts to retain this heritage,” Professor Spearritt said.

“Brisbane was a charming and rather old fashioned river port city until the 1960s, when the wharves were demolished and the freeway disfigured the city side of the river.

“Neither the Council nor the State Government recognised the colonial charm of Brisbane until the demolition of the Bellevue Hotel [in 1979] made the public realise that the city was losing a lot of its charm.”

By the 1960s and 1970s, “rather nondescript office blocks” were built in the city centre, Professor Spearritt said, as Brisbane’s development was largely overshadowed by the Gold Coasts’.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Professor Spearritt said the city began to attract some famous architects like Harry Seidler who built The Riverside Centre, which has 40 storeys and is 146m above ground, in 1986.

“It [was] getting some notable office blocks [during that time],” Professor Spearritt.

ICONIC BUILDINGS

University of Queensland’s school of architecture deputy head Dr Antony Moulis said Craigston on Wickham Terrace by Atkinson and Conrad in 1924 stood out as an early iconic building of Brisbane displaying revival style character.

“The Torbreck Apartment Building on Highgate Hill by Job and Froud, 1957-1961, remains one of Brisbane's most iconic projects and introduced the city to modern living,” Dr Moulis said.

“Other mid-century works include Karl Langer‘s strict modernist Department of Main Roads built in 1967 and the SGIO building by Conrad Gargett and Partners built in 1971.

“Clearly, Robin Gibson and Partners’ work on the Performing Arts Complex, Art Gallery and State Library through the 1970s and ‘80s reshaped the image of Brisbane.”

Professor Spearritt said in the 21st century, all of Brisbane’s tallest buildings, with the exception of the Government Office building, had been residential towers.

“This harkens back to 1957 when Torbreck at Highgate Hill emerged to briefly be the tallest building in Australia,” Professor Spearritt said.

THE EXPLOSION OF GROWTH

The World Expo 88 was a time of significant growth in Brisbane, ushering in more than 15 million visitors from around the globe and promoted Queensland as a top tourist destination.

Dr Moulis said the making of South Bank in the wake of Brisbane‘s Expo 88 marked the moment when the city’s urban infrastructure experienced its most significant growth.

“That impetus continues through to today with Brisbane‘s Olympic Games now on the horizon.”

Vecchio Property Group’s managing director Sam Vecchio said over the past 100 years Brisbane also saw increased infrastructure construction at the start to mid 2000s when council relaxed its zoning laws to allow “new and more transformative” properties from industrial to residential in zones like Teneriffe and West End.

“Multiple developers from down south and overseas started a big wave of development in the city,” Mr Vecchio said.

“The greatest change to Brisbane‘s skyline has happened in the last decade.

“The arrival of apartment living to inner areas such as South Brisbane and Teneriffe has altered the way we see and experience the city. It‘s given Brisbane a new sense of urbanity.”

However, Professor Spearritt believes that it was the 1970s when Brisbane began to truly take off, as before then, the city was “remarkably backward”.

“Its railway lines were not electrified until 50 years later than Sydney and Melbourne,” Professor Spearritt said.

“It redeemed itself in the 1990s with a clever busway system, with both the city council and the State Government agreeing to hang fast busways off the freeway system, especially to the south of the city.”

LOOKING AHEAD

With the preparation of the Olympic Games well underway in Brisbane, experts believe the city’s image and skyline will noticeably change.

Dr Moulis said the games would “clearly fuel” the momentum of the city’s architectural development, with ideas of sustainability and urban resilience at the forefront.

“The Games will be an important global event but its legacy for the city will also be important, even more so,” Dr Moulis said.

“The legacy development of South Bank that occurred post Expo 88 points the way to what the city must aim to achieve.”

Mr Vecchio said once the economy improved, there would be another wave of construction coming as Brisbane continued to be a city that attracts people and businesses.

However, Professor Spearritt believes the biggest architectural challenge facing the look and feel of central Brisbane was how it would retain some sense that it was Australia’s only subtropical capital city as well as honouring its historic charm.

“Brisbane is still to come to grips with the fact much of it is built on a flood plain,” Professor Spearritt said.

“Some heritage structures are now properly protected, but Brisbane as a city is still inclined to think that new is best.”

—

Ahead, we have collated a series of historic pictures of Brisbane CBD’s skyline over the decades, from the 1920s to today.

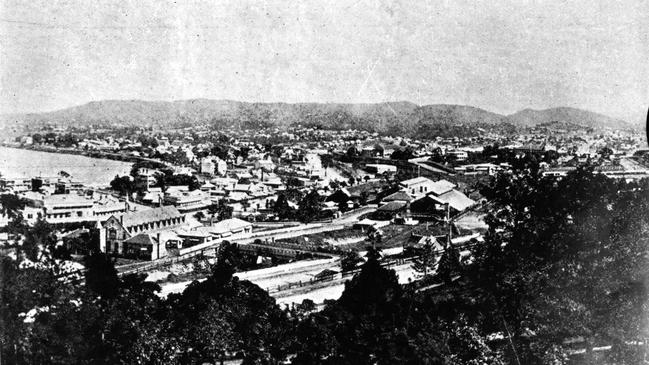

1920s

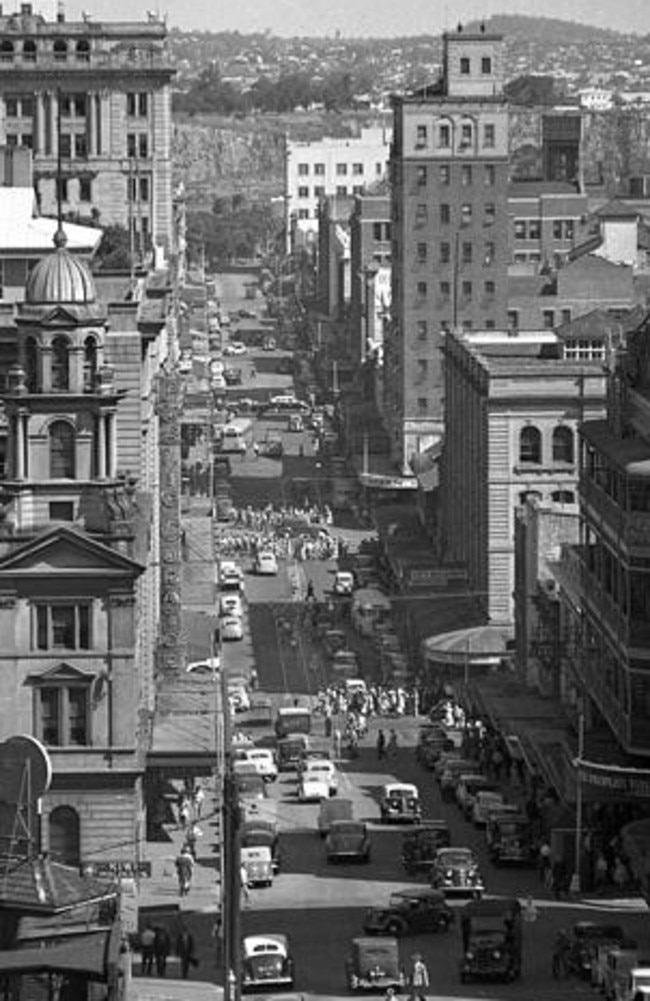

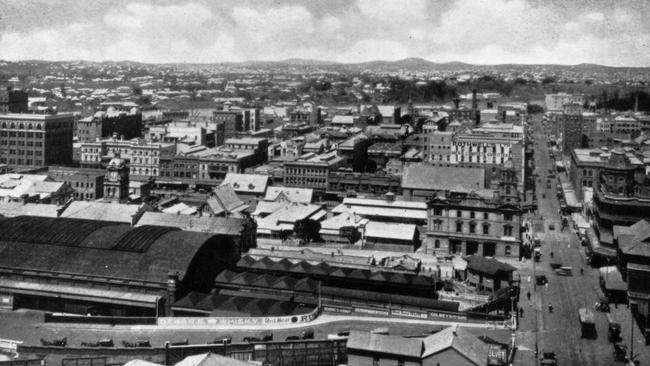

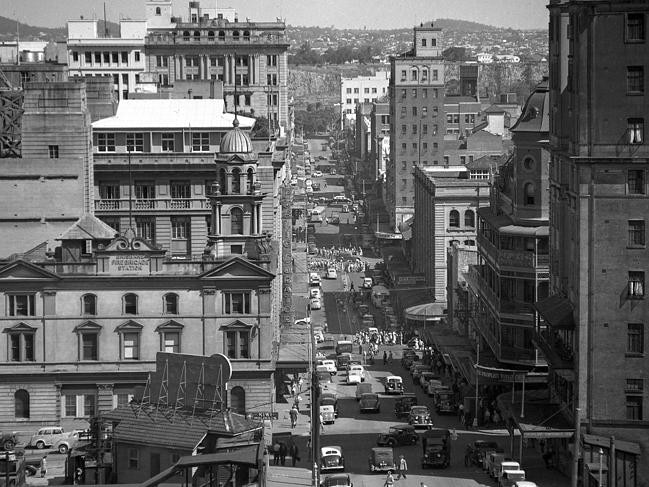

1930s

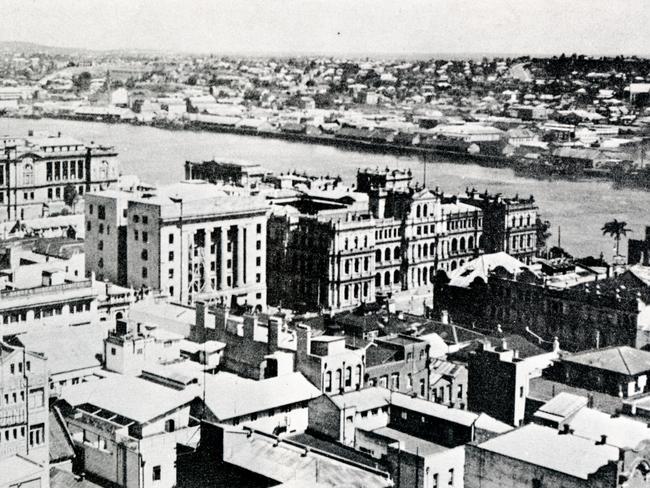

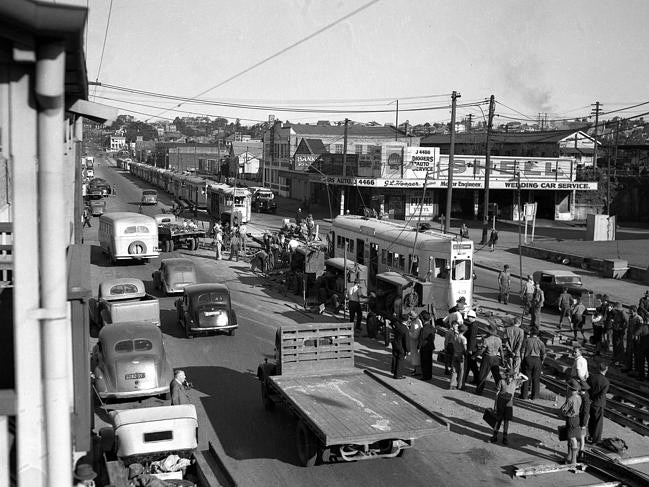

1940s

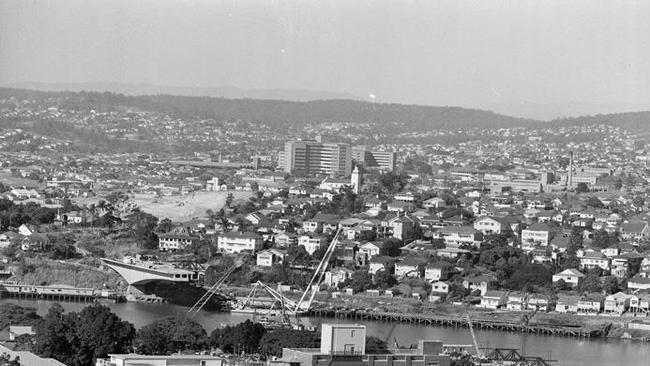

1950s

1960s

1970s

1980s

1990s

2000s

2010 – 2020s

More Coverage