One monstrous day in May, a child killer changed our lives

Little Stacey-Ann Tracy was raped and killed in 1990. Thirty years later, journalist SHERELE MOODY examines how Stacey's death impacted the lives of six women.

Sunshine Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sunshine Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Little Stacey-Ann Tracy was raped and murdered in 1990. Journalist SHERELE MOODY tells the story of how Stacey's death impacted the lives of six women over the past three decades.

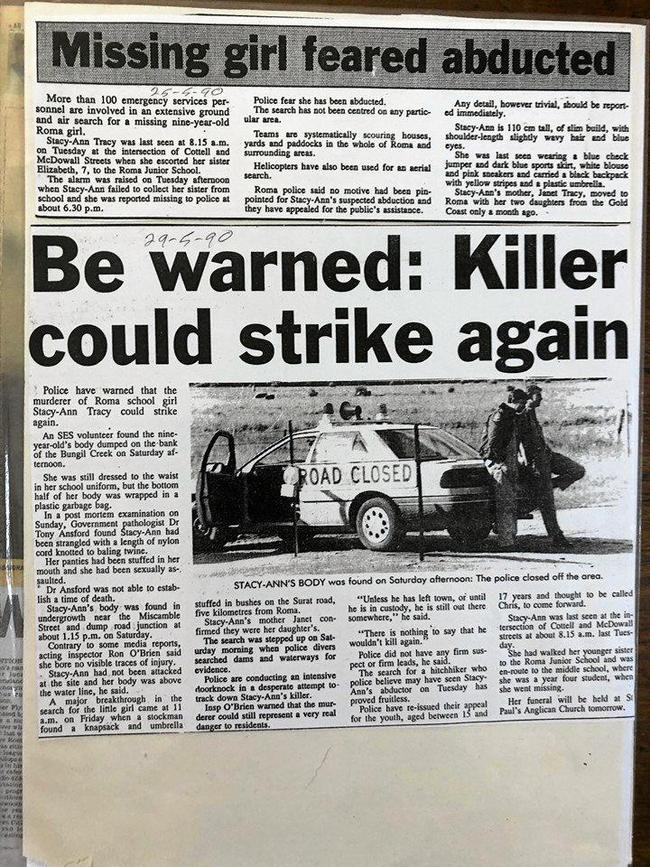

THEY found her small broken body slumped against a tree in the undergrowth by a dry creek bed.

She lay a few metres from a roughly hewn track connecting the nearby town to its rubbish dump, the heavy bushland shielding her from the view of passing motorists.

For four long cold miserable nights, she was crumpled against that tree - a nine-year-old girl scared of the dark discarded in death like rubbish.

In a rushed attempt to hide his hideous actions, he tossed her away with all the murderous accoutrements in place. A window blind cord wrapped tightly around her neck, its fibres cutting into her delicate pale skin; a splash of brightly coloured material grotesquely spilling from the corner of her mouth; a bruise, the size of his fist, darkening one of her cheeks.

Bizarrely, he tried to preserve her modesty, sliding her legs and waist into a used black garbage bag. Beneath the rumpled plastic her underpants were missing, her netball skirt askew.

A torn scrap of paper, covered in handwritten names and numbers, clung resolutely to one of her toes - a calling card of sorts unwittingly left behind by her killer.

The autopsy showed she had been raped before - and after - she died.

He shoved her own underwear down her throat to silence her screams during his vile assault. When she did not choke to death on the material, he strangled the remaining life from her body with the blind cord.

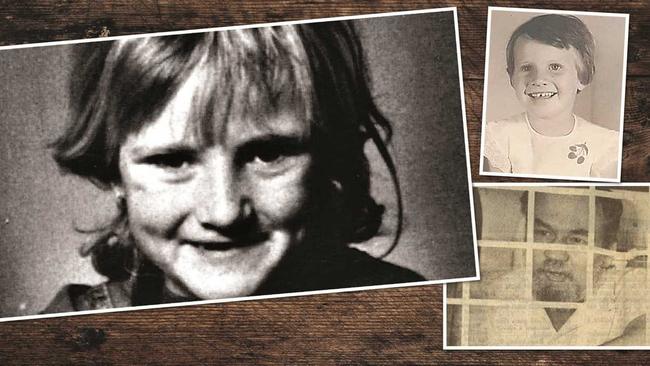

Her name was Stacey-Ann Tracy. He was Barry Gordon Hadlow.

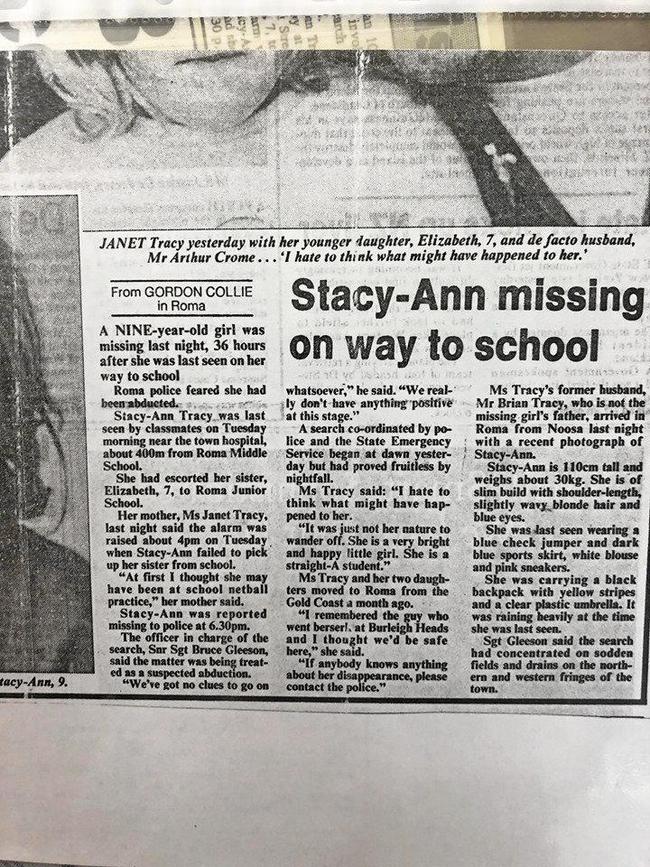

She disappeared as she walked to school in the Queensland town of Roma on Tuesday, May 22, 1990.

This is the story of that one monstrous day in May and the impact it had on Stacey-Ann's sister Elizabeth Tracy, her mother Janet Mills Clarke, her grandmother Joan Mills, her best friend Charlie Shaw, the detective who put her killer behind bars and the journalist writing this article.

'WE GOT THE LIFE SENTENCE. STACEY GOT THE DEATH SENTENCE. HE GOT BED AND BREAKFAST'

ELIZABETH Tracy was born 18 months after her big sister Stacey-Ann.

They may not have been twins, but the siblings were mirror images of each other. Both slightly built, blonde-haired blue-eyed lasses adored equally by their family.

While their physical features were eerily similar in that special sisterly kind of way, their personalities were worlds apart.

Stacey was a people person and a talented singer and dancer, blossoming in front of a crowd.

She was whip-smart, a dedicated student, popular with her peers and surrounded by large groups of friends. Her favourite sport was netball.

From the time she could walk and talk, she showed a fierce streak of independence.

Yin to Stacey's Yang, Libby was shy and reserved. She preferred her own company and that of close family. A learning impairment meant she struggled at school. Sport was not her thing but losing herself in the pages of her books was.

The differences meant nothing though, their bond was deep and abiding. It was a bond that could only be broken by death.

"We did everything together," Libby, now aged 37, says.

"Anywhere she went she'd say 'Libby's coming with me' - whether I wanted to go or not.

"I would have followed her anywhere."

Libby was often bullied and her big sister was not one to take the attacks on her sister lying down.

Libby recalls the day an older boy knocked her face first into the green grass of their school oval.

Stacey raced across the grounds and decked the young lad.

"She was always sticking up for me," Libby says.

"She felt she had to protect me."

Stacey shouldered the consequences of her actions with aplomb, not complaining after copping a dressing down from the principal and being sent home on suspension.

It was a small price to pay to keep her sister safe.

PURE EVIL: The child-raping murdering monster we can't name

From Michael Jackson and Madonna to the Rubik's Cube and the fall of the Berlin Wall, only those raised in the 1980s can truly understand the uniqueness of that flashy decade.

Like most young girls growing up then,' Stacey's fave toy was her Cabbage Patch doll and she would sing along to the synth-heavy energetic anthems blasting from her mum's radio or the cassette deck.

"She really loved Belinda Carlisle and her song Run Away Horses," Libby says.

"She'd drive us crazy when we went in the car, because she would always play that song on the cassette player.

"When the song ended, Mum would have to rewind it so she could listen to it again."

Libby was just seven years old when Stacey's song was silenced.

May 22, 1990 dawned wet and gloomy in Roma as a gentle rain soaked the town.

As was their habit, Libby and Stacey rose around 7am, donning the school uniforms their mother neatly laid on the end of their beds the evening before.

Janet was crook that morning, so the girls helped themselves to cereal and watched cartoons.

They kissed their mum goodbye and headed off on the short walk to the Roma Junior School campus where Libby's class was based.

"We had this little clear plastic umbrella," Libby remembers.

"We were both huddled under it.

"I'd lost mine, so she came into my class to help me look for it in the lost and found."

Stacey search for the umbrella was interupted as Libby's teacher urged her to hurry to her own campus, lest she be late for class.

"Stacey gave me a kiss and a cuddle and said 'I love you Lib. See you later'," Libby says.

"I said 'Yep, I love you too. Will see you then'.

"That was the last time I ever spoke to her or saw her alive."

Libby's day was quite ordinary until the clock's hands ticked passed 3.45pm - the time when Stacey was due to meet her so they could walk home together.

By 4pm, staff at Libby's school were concerned that the girl was still there so they contacted Janet.

Libby and Stacey had never known violence, their family made sure they were protected from the world's dark sides.

It was this shielding of their innocence that meant Libby could not imagine the worst outcomes for her sister.

Abduction, murder, rape - these were very much alien concepts yet she felt a dark foreboding alongside her worry and confusion.

That first evening without Stacey was a chaotic blur.

Janet and family friends searched the streets, school grounds, parks, ovals and public spaces to no avail.

Police came, asking Libby to repeat the morning's events over and over until she fell into bed at midnight, exhausted and broken.

"It was really daunting but I answered their questions the best I could," Libby says.

"I told them what had happened and the last conversation we had.

"I was worried and wanting to know what happened to Stacey.

"I wanted her to come home. It was really scary."

The next day, Libby went to stay with trusted friends who were under strict instructions to keep the youngster away from television news broadcasts and the daily papers. Janet did not want her exposed to speculation about her sister and what might have befallen her.

Libby was still at the friends' house on the day Stacey was found, her mother refusing to bring her home until her grandmother arrived from Melbourne to help break the news her sister was dead.

Losing Stacey-Ann was the first time Libby had faced death - she was far too young to fully understand the implications.

"My grandmother had to tell me about Stacey because Mum couldn't get the words out," she says.

"It was overwhelming.

"I don't think I totally realized that she was dead."

MORE FROM SHERELE MOODY: With small steps for Hannah, we can end the terror at home

Exactly a week after Stacey disappeared, Libby and her family gathered in the chapel at Roma's funeral home to say their goodbyes to the youngster.

In a small white coffin, surrounded by soft pink velvet, the little girl's body lay.

The mortician did their best to hide the injuries left behind by her killer.

Make-up covered the bruises on her face and the rope marks around her neck. She was dressed in a pink and white frock speckled with flowers and adorned with stripes.

A delicate gold bracelet clung to her little wrist and a golden chain with a heart-shaped locket graced her neck.

Too small to see into the coffin, Libby stood on a stool so she could kiss Stacey for the last time.

"I'll see you again soon," she told her sister.

Libby says when her lips touched Stacey's cold skin, she understood the true meaning of death.

"That was really hard to deal with," she says.

"It really broke me.

"I was sad for a very long time."

The crowd at Stacey's funeral was one of the biggest Roma had ever seen.

Graziers and grain growers, farm hands, shop assistants, teachers, doctors, uniformed police, detectives, industry leaders, politicians, SES volunteers, grandmothers, grandfathers, children and teenagers - it seemed on that day that there wasn't one person in Roma who was not touched in some way by Stacey's death.

After a moving service with traditional hymns and prayers and fond memories shared about her short life, Stacey's coffin was carried to the hearse and driven the small distance to the local cemetery.

Stacey is one of 4268 people buried in that cemetery. Her grave is covered by a neat pink and white tiled slab.

Sometimes, kind townsfolk place flowers in the vases that sit by her bronze memorial plaque.

Life after losing Stacey was tough for Libby.

Her family made every effort to keep the violent details of Stacey's passing under wraps, but the children of Roma were not so thoughtful.

Libby never fitted into the town like Stacey did. She wasn't the popular girl and those around her let her know it.

"After she died the other kids would tell me it should have been me who was raped and murdered," she says.

"They were really nasty.

"They were older kids and they should have known better."

Hadlow's decision to kill Stacey has had life-long ramifications for her sister.

It was nearly impossible for Libby to bond with anyone outside of her family and on the rare occasions that she started to get close to others, she would hold a part of herself back.

She feared those she loved would be taken away like Stacey was.

In a way, this terror has doggedly followed Libby throughout her life.

Even now, she prefers her books and her little dog Dobby to the company of people.

She is extremely close to her mum and grandmother but Libby has never married and cannot see herself having children.

"I don't think I would be as shy and reserved as I am because she would have made sure I met people and that I had friends and went out," Libby says.

"We got the life sentence. Stacey got the death sentence. He got bed and breakfast.

"I wouldn't wish this pain on anyone."

THE MIRACLE CHILD

STACEY-ANN was never meant to be, yet by miracle she existed.

Stacey's mother Janet had just turned 18 when doctors explained there was no chance she would ever have children.

Her inability to conceive, they said, was because of Janet's own rocky start to life.

Janet's mother fell pregnant with twins.

It's not known why, but one twin died in utero. The other twin - Janet - survived. As Janet grew within her mother's womb, her body absorbed her sibling's foetal tissue.

Known as vanishing twin syndrome, the loss of a baby this way occurs during the first trimester of about 30 per cent of multiple pregnancies.

While the syndrome doesn't impair the mum, surviving female twins are often born with the congenital condition didelphic uterus - or double womb.

Didelphic uterus impacts about 0.5 per cent of women and in the worst of cases it means they most likely won't conceive and if they do fall pregnant, they will miscarry.

After learning she wouldn't have kids, Janet and her boyfriend road tripped from Melbourne to Queensland.

One night in a small caravan at a park in the Brisbane suburb of Carina, Janet fell pregnant.

And - against the odds - she carried her baby to term.

On the evening of May 8, 1981 - after a mammoth 19-hour labour - Stacey screamed her way into the world

"They came to me at 6.30pm and said they'd have to do a Caesarean section if she wasn't born by 7.30," Janet says.

"She must have decided she wasn't having any of that (the operation) - she was born at three minutes to seven."

Janet was smitten.

"She was my world," she says.

"Stacey was such a happy baby - she slept all night right from the first night at home.

"She wasn't a perfect baby because there is no such thing, but she was as good a baby as you could get.

"She was bubbly and always happy - she reached her milestones like any normal kid.

"She was a joy to have - everyone adored her."

Janet remembers waking each night during the first months with her infant daughter, fearing the child's lack of crying and restful sleeping pattern might mask something sinister.

"I would freak out and was up every few hours to make sure she was still breathing, that she was still alive," she says.

"I didn't even go through the normal teething process like other parents do - where they are kept up all night."

BLOOD ON WHOSE HANDS? The epidemic we can no longer ignore

A baby's first birthday is often a time of great celebration for families and that was certainly true of Stacey's.

"For her first birthday, I got her a chocolate ice-cream cake," Janet says.

"I put her in her chair and left the cake a little too close while I went out to get the rest of the family.

"When I came back the cake was destroyed and she was covered in chocolate.

"It was such a funny sight - I couldn't be mad at her."

Always the clown, Stacey would often rope Libby into practical jokes on unsuspecting family.

Sometimes, those jokes went a little too far - like the one time she gave herself and her sister a haircut.

"I came out one morning and there was hair everywhere," Janet says.

"They both had beautiful long hair and it was gone.

"I just cried.

"It was a very bad haircut so we had to take Stacey to the hairdresser to get it fixed.

"She ended up with really short hair for her first day of school - I was absolutely gutted.

"This is one of my fondest and funniest memories of Stacey."

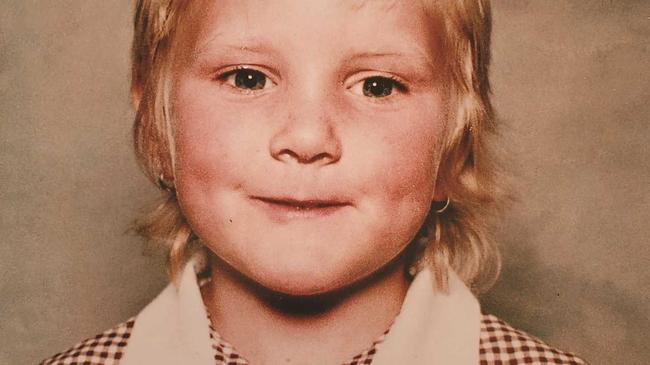

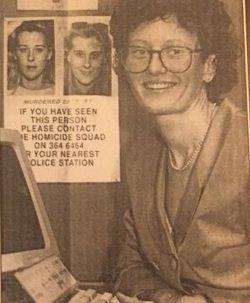

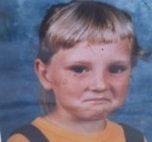

A few weeks after that disastrous meeting with the scissors, Stacey posed for her first school photograph.

Some three decades later, her brilliant blue eyes stare astutely at you. Her cheeky half-smile framed by tiny dimples, her tom-boyish blonde hair fluffing the edge of her uniform.

There's no mistaking the confidence in the five-year-old slightly freckled moon-shaped face peering from the aging photo frame.

"I can only remember Stacey missing one day of school and that was only because she hurt herself after falling off a waterslide," Janet says.

Janet and her girls lived in Melbourne, near their extended family, until 1989 when they swapped chilly Victoria for the balmy climate of Queensland's glitter strip.

A single mother for most of her daughters' lives, Janet had fallen in love with a man who was a "wanderer at heart".

Their move to the Gold Coast was spur of the moment, but it was one Janet believed would benefit her family.

They settled into a home just a stone's throw from Janet's brother at Palm Beach, embracing the coast's gaudy sun-tanned surfer vibe, the warm weather, the friendly locals and of course, the beaches.

On April 8 in 1990 their idyl was shattered, with the family having their first real brush with violence.

That morning, 26-year-old Satan-worshipper Rodney Dale dressed himself entirely in black.

With 666 carved into both of his hands, he dosed himself up on drugs and booze, smeared devil-worshipping words around his Burleigh Heads apartment and armed himself with a gun.

He wrote a short note to his girlfriend: "Deb, gone hunting XXXX".

Casually, he strolled the streets around the Coast, firing the weapon repeatedly and indiscriminately.

One of his bullets killed 77-year-old Kathleen Lewis. He also injured Kathleen's husband Llewellyn and six other innocent bystanders.

MORE FROM SHERELE MOODY: The terrifying life and death of Olivia Tung

This act of violence chilled Janet to the bone.

Wanting desperately to get her daughters out of the area, she agreed when her partner suggested they move six hours away to a place she'd never seen, let alone heard of.

Roma is a thriving agricultural town nestled in Queensland's Outback, some 400km west of Brisbane.

Incorporated in 1867, the town was named after Lady Diamantina Bowen (nee di Roma), the wife of then Queensland Governor Sir George Bowen.

The region's original custodians are the Indigenous people of the Mandandnji Nation.

White settlers embraced the district for its fertile soil, claiming large tracts of land as their own to grow wheat and raise livestock.

By the time Janet and her daughters arrived, it had morphed into the mini-capital of western Queensland and was home to a little over 6000 residents.

Roma had everything a young family needed - a large base hospital, three schools, police and emergency services, fuel stations and a small shopping centre.

With a low crime rate, quiet streets, quant cottages, fresh air and lots of open spaces, it seemed the perfect place to raise to two little girls.

"Yes, to us it was the middle of nowhere," Janet says.

"I'd never been there, but my partner had.

"He was really taken with it and I guess that and the man shooting up the streets where we lived was how he talked me into going there.

"I made the decision to move there because I honestly believed Roma was safe - that my kids would grow up there and we wouldn't have to worry about their safety."

Caring for two little girls and suffering crippling migraines, Janet made ends meet on her meagre pension with the help of her own parents.

Arriving in Roma, they had to wait for a Department of Housing property to become available so they rented rooms on the second storey of the historic Queens Arms Hotel.

Lodging in one of the town's busiest drinking holes was far from ideal, but Janet made sure the girls never went into the bar area.

Had they frequented the bar, chances are high that they would have run into Hadlow who was a regular there.

He and his wife Leonie - mother to eight children - were integral members of the pub's competitive darts team.

Not far from the CBD, the hotel was also an easy five-minute walk from the Roma State College's two campuses.

Libby attended the junior campus's Year 2 class on Bowen St while Stacey enrolled in Year 4 at the middle school on Cottell St.

The walk between classes was barely three minutes and it was one Stacey and Libby made five days a week without problem.

Janet, Stacey and Libby settled well into Roma's laidback way of life.

Stacey in particular embraced her new hometown, joining her school's netball squad and quickly becoming one of the most popular girls in her grade.

On the evening of May 21, 1990, Janet prepared dinner before taking Stacey and Libby's uniforms and under-things out of their cupboards and arranging them neatly on the end of their beds.

In agony from a migraine headache, she had her painkillers and kissed her daughters goodnight.

"I love you. I'll you see you in the morning."

These were the last words she spoke to her eldest daughter.

Early the next day, Janet woke to the rain streaking down the hotel's windows, remaining in bed fighting the agonising pain in her head and listening to the girls chattering as they dressed.

Childish giggles bounced off walls while cartoons played on the TV, young voices falling quiet from time to time as spoons clinked against bowls filled with milky Fruit Loops.

After breakfast, Libby and Stacey popped their heads in to kiss Janet goodbye.

Janet's partner offered to walk them to school or to get them a taxi, but the rain outside was not heavy enough to deter headstrong Stacey.

She cherished the little bit of independence that came with taking her sister to school and she was not about to let the weather rain on her parade.

Shortly after the girls left, Janet made her way to the breakfast table and settled in for her morning coffee and cigarette while planning her day.

It was payday, so she went to the local shops to buy the girls some new clothes and to stock up on groceries before returning to the hotel.

Around 4pm, she received the call from Libby's teacher.

In many ways wise beyond her years, Stacey was not one to shirk her responsibilities so her failure to turn up triggered alarm bells

"She was never late home from school. Never," Janet says.

"This was very much out of the ordinary."

Janet called Stacey's school, only to be told her daughter had not been in class that day and that no one on staff thought to let her know.

"I knew that if she had not made it to school that morning then something terrible had happened to her," Janet says,

"I went searching for her.

"I walked through those streets where she would always walk and I just could not find her."

Janet contacted the parents of Stacey's classmates but this was also to no avail.

At 6pm she reported her daughter missing to police.

A missing child investigation started immediately, with detectives from the state's homicide squad summoned from Brisbane.

"I did not know what to think had happened but the police from the start were concerned she had been abducted," Janet says.

"The police were very quick off the mark; they were just brilliant.

"I can't say a bad thing about the police or their investigation."

There were moments over the following days that Janet believed her daughter would be found safe.

As frustrated and stressed as she was, the mum had no choice but to wait patiently while residents, State Emergency Service volunteers and police searched for her daughter.

Janet did not know it, but one of the people looking for her daughter was the man who killed Stacey.

Two days into the search and the first trace of Stacey-Ann emerged when her school bag was discovered tossed on the embankment of a road not far out of town.

Four days after she disappeared, two men found Stacey's body in the bush near the Bungil Creek.

"I wasn't sleeping - I had not slept at all for days," Janet says.

"I was pacing around a lot. I was smoking too much.

"I didn't go out because I did not want to speak to anyone.

"My stress levels were very high. I was falling apart.

"Then about 1.30pm on the Saturday, there was a knock at the door."

Detective Gayle Hogan, from the Queensland Homicide Squad, and Graham Hall, from Roma Police, were there to deliver the worst news.

"I took one look at their faces and I knew she was dead," Janet says.

The officers explained a child's body had been found and they would need someone to identify the victim.

Janet wanted to wait for her mother Joan to arrive from Melbourne but police needed the identification done as soon as possible.

Behind the Roma Hospital stands an old tin shed. In May of 1990, this ramshackle hut doubled as the town's makeshift morgue.

Inside, Stacey-Ann's body lay on a folded gurney resting atop a large cement slab.

A sheet covered her from her feet to her neck, but her little face was clearly visible.

Janet was not allowed to enter the room to touch her daughter.

Standing in the doorway, a metre or so away from Stacey, Janet could clearly make out a dark hand-shaped bruise on her cheek,

The police told her they thought the brightly coloured material poking from the side of Stacey's mouth was a handkerchief.

"No," she responded. "That's the underwear I laid out for her the night before. It's her knickers."

"I've lived with that image of my daughter for three decades - I have never been able to wipe it out," Janet says.

"I couldn't even touch her or kiss her, because the autopsy had not yet been done.

"No mother should ever have to see their little girl like this. This is what that monster left me with."

Despite her deep shock, circumstances deprived Janet of the time and space she needed to reflect on what had happened to her daughter.

Back at the hotel. a huge throng of journalists, photographers and TV camera operators waited for her arrival.

"The media were really in my face," she says.

"As I got out of the car, they crowded around me, they were jostling me and asking questions about what I saw and what had happened to her.

"I hadn't even had time to process identifying my daughter's body, but they were everywhere.

"It was a really really scary moment for me.

"I just wanted to go home and let it all sink in."

The day after Stacey was found, police let Janet know they had a suspect and that officers were watching his home.

They did not tell her who he was or how they came to find him, but they assured her he would be charged before Stacey's funeral, which was to be held in three days.

True to their word, Hadlow was charged on the Monday with Stacey's murder and with sexually violating her.

While Janet found out Hadlow's name after he was charged, she was kept in the dark about his previous offending.

It was only at his committal hearing a few months later that she learned he had been convicted of child rape at the age of 16 and that he was on parole for the rape and murder of five-year-old Sandra Dorothy Bacon in Townsville when he did the same to Stacey.

In November of 1962, Hadlow lured little Sandra into his home, telling her he had some books he needed her to pass onto her sister.

When she screamed for help he tried to strangle Sandra to death.

Sandra was a tiny girl but she fought for her life. He killed her by stabbing a large hunting knife straight into her heart, later confessing "she wasn't dying fast enough".

After killing Sandra, Hadlow wrapped the bottom half of her body in an old corn sack and tossed her into the boot of his car.

That evening he joined the search for the child, even approaching her mum and dad to tell them he understood their pain because once "his brother had gone missing for four days".

A few days after killing Sandra, cops found her body in his vehicle and they arrested him.

"Yes, I've killed her," he told them.

"I've been expecting you to pick me up".

After serving his 22 years, a sympathetic parole board fell for Hadlow's claims that his new-found love of God and the bible were enough to keep his vile urges at bay.

Janet still holds a lot of anger towards the parole board. She knows her daughter would still be alive if he had remained locked up.

"He was a monster and they let him go," Janet says.

"He had shoved Stacey's knickers so far down her throat that he blocked her airways.

"He raped her before she died and after she died.

"He tossed her out of his car like she was a sack of potatoes.

"I saw a photo of her body that was presented at trial - She was slumped up against a tree.

"No mother should have to go through this."

Janet says she came close to killing Hadlow as he sat in the dock during his trial at Brisbane Supreme Court.

"It was so gut-wrenching for me to hear what he had done to her," she says, revealing she considered grabbing a police officer's gun to shoot the killer.

"I wanted to strangle him with my own hands.

"In that moment, I would have shot him and saved the taxpayers a lot of money."

On March 15, 1991, a jury of seven men and five women convicted Hadlow of Stacey-Ann's murder.

In marking Hadlow's file "never to be released", Justice Tom Shepherdson said a "dreadful mistake" was made when authorities gave Hadlow the keys to his freedom after he killed Sandra Bacon.

Justice Shepherdson said it was clear from a psychiatrist's report given to the parole board, that Hadlow was an ongoing danger, his penchant for sexually violating and killing girls would never be curtailed.

"I cannot understand how anyone who had the opportunity to read the psychiatric report could have allowed you to be released," the justice said.

As he was being led from the courtroom, Hadlow yelled: "I'm being crucified like Jesus".

"They'll get their's the lying dogs," he continued, directing his anger at police, the prosecutor and the witnesses who gave evidence against him.

Unwilling to leave Stacey alone in Roma cemetery, Janet remained in the town for around two years after her death but there were always reminders of Hadlow's actions.

"I'd walk down the street and I'd hear people say: 'There's that woman whose daughter was killed'," Janet says.

"It just became too much, having them remind me all the time of what had happened.

"The last thing I ever wanted was to be away from Stacey but I also had a daughter who was still living and she deserved for me to give her every opportunity and to have a chance to not be constantly reminded about what he did."

It doesn't matter how much distance Janet puts between herself and the town where her daughter died, time and space refuse to let her heal.

The past 30 years have not been kind to the now 58-year-old.

The deep-seated trauma of losing her daughter to such a callous and cold-hearted act of violence means she has taken its toll mentally and physically.

About 14 years ago, Janet had a heart attack and has since had five stents put into the failing organ.

"My doctors believe the heart attack was the direct result of the stress of losing Stacey-Ann," she says.

"I have been on medication since Stacey died because I got the triple booby prize of PTSD, depression and anxiety and it's all thanks to that one person who ended her life and upended ours."

Janet was recently diagnosed with emphysema; she has diabetes and she still suffers from chronic migraines.

Often well-meaning people tell her that life will improve if she forgives Hadlow and lets Stacey go, but this is impossible.

"There's always reminders of Stacey," Janet says.

"Her birthdays, Christmas and Mother's Day - they are always the hardest moments for me.

"Each year I light a candle at midnight on her birthday and it burns until midnight.

"And I do the same on the anniversary of her death and at Christmas time.

"These are times of quiet reflection for me and my family."

Stacey may be gone in body, but her spirit is always close.

A candle flame flickering out in a draft-free room; her framed photo randomly falling from a shelf; the feel of tiny cold fingers softly touching Janet's arm - these ghostly moments are evidence, she says, that Stacey is nearby, watching over her family.

"Stacey will be with me until the day I die," her mum says.

Janet and Libby moved to Bundaberg this year to be closer to her mother Joan.

It's been around 28 years since she visited Stacey's grave.

Janet hopes to make the trek to Roma soon, to lay flowers atop the final resting place of her beloved daughter - but first she must find the strength to face the town where evil wiped out so much promise.

'WHY WOULD SOMEONE WANT TO HURT OUR LITTLE GIRL LIKE THIS?'

"I NEVER thought I would outlive my grandchild," 80-year-old Joan tells me in the weeks before the 30th anniversary of Stacey-Ann's death.

'When she was killed it broke my husband's heart - he changed overnight and he never really spoke her name again."

Joan fell in love with Gordon Mills about 60 years ago at a community dance in Nathalia, a small town in the northern district of Victoria.

Two years later they married, moving to Frankston where they bought the house they would call home for 48 years.

Gordon, like many men of his generation, was a stoic bloke who rarely shared - or showed - his feelings.

The painter and decorator laboured long hours while Joan juggled mothering duties with working in a range of jobs including at a school for hearing-impaired children, in a library and at a local bakery.

Everything in Joan and Gordon's life revolved around their family. They loved their three daughters and their son, raising them in an honest home overflowing with kindness and laughter.

They may not have had much money but their's was a life rich in so many other ways.

They welcomed their first grandchild with open arms, doting on Stacey-Ann and taking her on adventures.

"When she was about 18 months old, we went to the zoo," Joan says, when I ask about her favorite memories of Stacey.

"I took her into the pygmy monkey display and she started yelling 'Look at him Nanna, look at him' while pointing at the monkeys.

"She was so cute that all the tourists were taking photos of her, not the monkeys.

"Stacey was a joy to be with - she was happy and she never caused any trouble.

"People just loved to be around her."

Late in the evening of May 22, 1990, two police officers arrived at the Mills' home.

They were there, they said, to let Joan and Gordon know Stacey was missing and that there were concerns for her safety.

Living some 17 hours from Roma, there was little Joan and Gordon could do other than to hope their granddaughter was found safe and sound.

The stress and worry was made worse by limited communication with Janet, whose only access to them was via the hotel's phone in reception.

Morning and night, Joan called the police station in Roma to get updates on the investigation.

"We were frantic but we always hoped Stacey would be found safe," Joan says.

"It was hard being so far away, but the police were fantastic."

Four days after Stacey disappeared, two cops knocked again on Joan's door.

"It just broke my heart," Joan says of learning her granddaughter had been murdered.

"It destroyed my husband - he just went into shock.

"Neither of us could understand how this happened - why would someone want to hurt our little girl like this?".

Joan booked a seat on the first plane to Brisbane and by Sunday evening she was in Roma.

Distraught and devastated, she set aside her own heartbreak to support her daughter and Libby.

Janet was in no shape to find the words - or the strength - to tell Libby what had happened so that difficult conversation fell to Joan.

"Telling Libby that Stacey was dead was the hardest thing I've ever had to do," Joan says.

"There's no manual for this.

"There are no instructions anywhere that tell you how to get the words out, how to tell a little girl her sister is never coming home.

"I don't know how I did it, but I did.

"I sat her down and I said to her, 'Stacey's not coming home'.

"She asked 'Why, is she sick?

"I said 'No'.

"She said 'Has she run away'. I said 'No'.

"Then she looked straight at me and said, 'Is she dead'. I had to tell her 'Yes'.

"That just broke my heart."

Joan helped organise Stacey's funeral, choosing her burial clothes with care.

"I was in the local dress shop and all they had were the winter clothes," Joan says.

"I wanted her to have a pretty summery frock but they didn't seem to have any in stock.

"The shop owner said to me 'Is this for the little girl who was murdered?'.

"When I told him it was, he brought out all their summer stock so I could choose one for her.

"Stacey loved dresses, flowers and anything that was pink.

"So that's what I gave her - I gave her a dress that she would have been proud of."

Joan carried a lot of anger after Stacey's death, but she felt unable to express her grief because she needed to be strong for her husband, her daughter and for Libby.

One small moment in the dead of night one year after Stacey died, gave the grandmother a chance to embrace her own pain.

"I just never cried - I had to hold myself together for everyone," she says.

"Then on this one night, I woke up to see a little girl in a party dress at the end of the bed.

"She had no socks or shoes on.

"I got up and said to her 'We need to get you some socks and shoes'.

"She said to me: "Nanna, where I live, I don't need socks and shoes. Tell Mummy I'm happy'.

"That just turned the waterworks on for me.

"I thought I was going crazy but Stacey was only buried in a dress - we never put shoes and socks on her."

THESE LITTLE GIRLS WERE FRIENDS FOR LIFE, UNTIL EVIL CAME

CHARLIE Shaw knew from the moment she met Stacey-Ann that they would be great mates.

"I remember seeing this new girl at school and she was really nice," Charlie says,

"She had the loveliest smile.

"I was hanging around with everybody, so I thought I'd befriend her and introduce her to the other kids and show her around the school - you know just hang out with her and help her with our schoolwork.

"We became very close very fast - we fit well together.

"What she could do, I couldn't do and what she couldn't do I could do.

"She was my best friend."

Most days, Charlie and her own sister would stop by the Queens Arms Hotel to join Stacey and Libby on their walk to school.

After school, Stacey and Charlie visited each other's homes or they'd while away the hours at a nearby park.

Charlie and her family lived in the same small unit complex as Hadlow and his family.

Charlie's father and Hadlow struck up a friendship, often helping each other with repairs and the like.

"I always had this feeling that he was the type of person to stay away from," Charlie says of Hadlow.

"There was something about him that really scared me - he just gave off this bad vibe."

Perhaps it was coincidence, or perhaps there was something sinister at play, but on the afternoon before he murdered Stacey, Hadlow came in contact with the youngster for the first time.

The girls were goofing around in the shared area of the units where Charlie lived.

Hadlow wandered into the space and Charlie - a polite well-mannered child - introduced Stacey to him.

After a brief conversation, Hadlow left.

The next morning, Charlie's father asked Hadlow to drive her and her sister to school because it was raining and the family did not have a car.

Hadlow agreed.

Charlie suggested dropping by the hotel so they could give Stacey and Libby a lift.

However, when they got there, the girls had already left so Hadlow dropped the Shaw siblings at school and drove off.

"I really had this very bad feeling that something had happened to her," Charlie says of not seeing her friend in class that day.

As the days passed and the search for Stacey continued, it dawned on Charlie that she might never see her friend again.

"I had a very bad nightmare a night or two before her body was found," she says.

"I'd never had a dream like that.

"When I woke up I realised something bad had happened to her."

It's hard enough losing a friend to murder, but Charlie's experience was made worse by the fact that she had to give evidence at Hadlow's murder trial.

She remembers sitting in the Brisbane Supreme Court witness box, directly across from the monster who ended Stacey's life.

"That was the scariest day," Charlie says.

"It was horrible.

"I was a 10-year-old girl facing somebody who had hurt one of the closest people to me.

"I had to talk while he listened to everything I said and while he watched me.

"It was really scary - I couldn't look in his direction."

MORE FROM SHERELE MOODY: Genius, nerdy, shy, fun - this is the real Priscilla Brooten

Charlie feels her life's trajectory probably changed because of Hadlow's actions.

"I don't remember how I dealt with it but I do know that I was very scared to walk alone and I would often go past where her body was found, and that would bring all the pain back for me," she says.

"It's impacted me as a mum - I am over-protective of my children. I won't let them spend time with people I don't know."

Now aged 39 and mother to four kids and grandmother to one, the Gympie resident says no other friendship had the depth of feeling that her mateship with Stacey had.

"I know that being friends with her made me a better person," Charlie says.

"I still really miss her. I wonder what she would be like now.

"She was a beautiful person and I wish to God it hadn't have happened to her.

"The world would have been a better place with a nice person like her in it."

THE DETECTIVE WHO BROUGHT THE COPYCAT KILLER TO JUSTICE

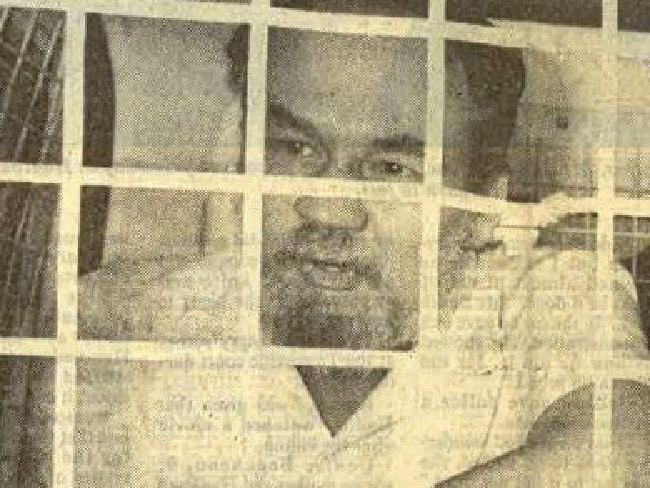

DETECTIVE Gayle Hogan arrived in Roma late on the evening of May 22, 1990 to investigate Stacey's disappearance.

Then a 12-year veteran with the Queensland Police Service, she knew the chances of finding the nine-year-old alive were low.

Gayle joined the force at the age of 19, inspired by an incident that happened to her when she was a youngster.

From directing traffic on the Storey Bridge in Brisbane to dealing with the rough and tumble miners in strife-torn Mt Isa, her time walking some of the state's toughest beats moulded her into a straight-talking no-nonsense ethical cop with a high regard for following the letter of the law.

After a lengthy stint investigating sex crimes, she became the first female detective in what many back then considered policing's elite boys' club - the Queensland Homicide Squad.

Putting emotion aside, the 31-year-old detective approached Stacey-Ann's disappearance calmly and patiently.

She was determined to "dot every I and cross every T", knowing from experience that one misstep could see the killer go free.

"As police officers, we need to keep an open mind about what has happened," she says in a phone interview from Canada, where she has just retired from her role as a chief investigator with British Columbia's police watchdog.

"When we started the investigation there was hope in my heart that she would be OK and that everything would turn out alright for Stacey and for her family.

"But I also needed to be mindful that this outcome might not happen - that meant having a frame of mind that allowed us to gather all the evidence we could find."

Stacey-Ann's killer had a 9½-hour headstart on police, with the youngster being abducted about 8.30am but the investigation not beginning until around 6pm.

Roma's police station is a small neat non-descript building facing the town's main street. It's easy to mistake the cream facade topped by a red roof for a normal family home.

Outside, the well-kept lawn and garden are dominated by a large white cement sign adorned with the QPS insignia and the station name.

Inside, the building is a rabbit warren of offices. Out the back, a short cement path connects the rear of the station with the town's small watch-house.

Gayle and her homicide boss, Detective Sergeant Bob Pease, coordinated their meticulous investigation with Roma's detectives and uniformed officers.

One of their first jobs was searching the police database to track down any potential offenders, including convicted child sex abusers, murderers or other criminals with a propensity for violence against children.

Hadlow rose to the top of the list as soon as the cops read his history.

He may have been able to hide his evil past from Roma locals, but he could not hide it from the police.

While he was their prime suspect, Gayle says their hunch needed to be backed up with evidence including finding items linking him to Stacey and witnesses placing him with the girl or at the multiple scenes of crime - the abduction point, the house where he killed Stacey and the creek where he dumped her body.

"We looked at the people who might have had contact with Stacey," she says.

"We had one person tell us they saw him driving around with what appeared to be a little blonde head visible in the car's window.

"That made us think he might have had Stacey in his car - that really concerned us as we knew there were no children of that age at his home."

Police were stationed near Hadlow's home to keep him under surveillance while detectives took to the streets to speak to locals about what they might have seen.

They tracked down a woman who had given him a lift into town after he ran out of petrol on a quiet road on the day of Stacey's murder.

Searchers found her backpack and umbrella in the area of the breakdown.

A witness who lived next door to Hadlow's home told police he saw a little blonde-haired girl running from the home and a large man fitting the killer's description chasing her down and dragging her back into the house.

Police also found a number of items from Hadlow's home - including a bed sheet - near Stacey's body.

The piece of paper found on Stacey's toe was the real clincher though - it was a darts' score sheet, the other half of which was found in the Hadlow household.

The person who wrote the numbers and names on the paper was Hadlow' wife, Leonie.

While Leonie refused to cooperate with police, it must be stressed that she played no role in the murder of Stacey and was having coffee with a friend when Hadlow committed his vicious crime.

"All of this gave us a clear indication that he was the person responsible for Stacey's death," Gayle says.

"At that stage, and because we felt we had the evidence we needed, we brought him in for an interview."

Gayle and Detective Pease spent hours grilling the 47-year-old, but he consistently denied having anything to do with Stacey's murder.

"No way, no way," he repeatedly told them during the interrogation.

Gayle recalls a frustrating moment when she believed he was on the verge of confessing.

Back then, cops relied on tape machines to record their interviews with crooks.

When the tape ended, the machine gave a loud buzz, ensuring police knew to insert a new cartridge before continuing the interogation.

"There was a point in our interview with him when everything became very, very quiet," Gayle says.

"Sometimes in interviews there are silences.

"We don't try to fill those silences with conversations or questions because we want to allow the suspect a chance to say something they might want to say about the crime - something they might want to get off their chest.

"He was really quiet for some time and I remember thinking he might be about to confess because his demeanor was different.

"Then there was this loud noise - the tape had stopped and the buzzer went off.

"It startled all of us - I really do think it stopped him from talking to us.

"Once the machine buzzed his demeanor changed and he went back to denying it.

"It was very a very frustrating moment for myself and my colleague because we did feel that we were going to get a confession at that point."

Looking into the eyes of a child rapist and killer is something not many people could do without emotion, but calm in the face of evil is something Gayle has perfected over her 40 years in policing.

"It is just so important to remain professional," she says.

"You just don't want any emotion coming through that may impact on getting the best evidence.

"So, no matter what I feel for the individual and what they may have done - it is very important that I just go out and do my job.

"I knew I couldn't bring this child back, but I also knew that I could not do anything that might have impacted on the integrity of the investigation."

One of the most important tools in an investigator's arsenal is the ability to gain the trust of those close to the victims - it's their stories that might hold the clues police need to solve a murder.

Gayle was the primary police contact with Stacey's mum Janet.

"From the start, I wanted to ensure that Janet trusted us and that she knew we were there and we were going to do our level best to find her daughter or - if it was the worse-case scenario - find out who did it," Gayle says.

"The biggest thing was to make sure Janet had confidence in us and that she knew we were there to do whatever we could.

"Looking back now, I do hope that was what I was able to do."

When a murder victim is found, a family member is required to officially identify them by attending the morgue to view the body.

This is a tough process for the loved one but it is also hard for the officers accompanying them.

Gayle was the officer who took Janet to that lonely tin shed where her child's body lay.

"Seeing the body of a murder victim is always hard, but I know this was not as hard for me as it was for Stacey's mum," Gayle says.

"I just wanted to help her to get through the process of identifying her child - I wanted to do it in the best possible way for Janet.

"So yes, it is very emotional, but I have ways of protecting myself and this is important because I need to put my feelings aside so I am able to do the best for the person in this situation.

"I know that if I do my job right, then this process will work out fine."

The meticulous investigation by Gayle and her colleagues meant Hadlow was convicted.

She says she never had any doubts that the jury would find guilty the man the media labelled The Copycat Killer.

"We knew we had the evidence and we always had faith in the system," she says.

The list of killers Gayle has put behind bars is long and includes some of Australia's most heinous individuals.

In 1989, about six months before Stacey was killed, a young woman stalked and murdered a man on the banks of the Brisbane River. Tracey Wiggington committed the crime with three other women, but it was her decision to drink the victim's blood that saw her dubbed the Vampire Killer.

In 1991, Gayle investigated the murder of 19-year-old Cheree Richardson on the Sunshine Coast. Cheree was killed by Bevan Meninga, whose brother Mal is now a Queensland rugby league icon.

She also helped put away Bentley White who raped and strangled to death Robyn Jane Kennedy in 1990; and she was an integral part of the multi-state apprehension of Robert Steele, Leonard Leabeater and Raymond Bassett.

These three thugs went on a two-state nine-day killing spree in 1993, ending the lives of 14-year-old Deborah Gale as wells as Mark Barlow, Anthony Percival, Gordon Currell and Robert Miller.

Born and raised a Roman Catholic, 61-year-old Gayle no longer attends church regularly but stresses that her spirituality and faith in God have helped her get through the many extremely tough moments in her career.

"Religion is just one part of me, but it does not dictate everything I do," she says.

"I do believe in God and all the principles of being fair and honest, making sure I'm the best person I can be and that impacts everything I do."

After leaving the Homicide Squad, Gayle managed Toowoomba's Criminal Investigation Branch and was eventually appointed an assistant police commissioner.

She retired from Queensland Police Service in 2015 and spent the past five years with Canada's Independent Investigations Office, where she oversaw investigations of deaths and serious injuries in police custody.

She expects to return to Australia with her husband Peter in August, with plans to retire in southeast Queensland.

Speaking in the days before the 30th anniversary of Stacey's murder, Gayle reflects on the little girl's legacy.

"This is a time when I think of Stacey and of the people impacted by her death," she says.

"Stacey and all of the other victims stay with me in many ways and I often think about the way they have influenced my role as a police officer.

"As a direct result of investigating Stacey's death ... I was able to make sure our investigation processes improved and my experience ensured those within Queensland Police dealt with a myriad of things better so that people could trust in us as police and in the organisation itself."

MY STEPFATHER, THE MONSTER WHO KILLED AND KILLED AGAIN

ON the day my stepfather was charged with Stacey's murder, I sat on the backstep of the Roma Police Station, looking into the watchhouse.

I stared at him through the wire cage and he stared back at me. Not a word was exchanged. I wanted to yell at him, to ask him why? But I was not brave enough and soon the moment passed.

I was furious at him. I was distraught that an innocent little girl had been subjected to such brutality. And I was concerned for the safety and well-being of my own sisters.

I had many questions for him and the police, but mostly I wanted to know why he chose to rape and murder?

No one has ever been able to answer that question - not the police, the lawyers, the judge or the experts on violence.

And certainly not Hadlow.

Although he made some boasts about his actions to fellow prisoners, he never admitted officially to the killing of Stacey and so he went to his grave in 2007, without revealing why he was the way he was.

Hadlow married my mother barely months after he was released from prison in 1985, with both telling myself and my siblings that he killed a man in a barfight.

Who were we to know better?

Back then, it was very hard to deep dive into a person's history. There was no Google, no online archives of newspapers and no easily accessible databases of violent perpetrators to check.

It wasn't until after he was charged with Stacey-Ann's murder that the truth of his past came to light.

Hadlow was - to be blunt- grotesque inside and out.

My stepfather was a loud obnoxious man who always managed to make himself the centre of attention.

If you told a story, he would tell a similar story but it would be bigger, louder, bolder and more incredible - yet for all his grandiose boasting, he was remarkably efficient at hiding his own horrific secrets.

Standing over six feet tall, Hadlow was a giant of a man with broad shoulders, hefty chest and huge legs.

Slightly arched eyebrows framed his cold piercing eyes.

A deep furrow marked his heavy forehead. His nose was wide and bulbous and a messy greasy greying beard and moustache framed his thick pale lips and hid his protuberant chin.

He called his beard "the soup-strainer" because crumbs of food would often get tangled in it, falling out when he'd stroke the long whiskers.

He rarely bathed, he reeked of BO and his hair was unkempt and straggly, slicked back by a disgusting mixture of Vaseline and scalp grease.

He was morbidly obese, drinking gallons of sugary drinks a day and hoovering down dish after dish of food. His favorite meal was boiled pig or sheep head. He'd eat every part of the poor things - shoving the eyes, tongue and brains in his mouth with dirty fingers - and licking the bones dry.

The thing I remember most about Hadlow though, is his hands.

They were massive and they were cruel, squashing cockroaches with the flat of his palms as they scurried on benches or walls; breaking the necks of puppies, kittens and other tiny helpless animals with a quick twist of his wrist.

It saddens me to know that those repulsive lumps of fleshy meat gripped Stacey and Sandra's delicate throats, squeezing the life out of their bodies.

My mother lived an itinerant lifestyle, dragging her eight kids from home to home across NSW - from Camperdown in Sydney to Casino in the Northern Rivers district.

When I was 15, she headed to Queensland.

Shortly after arriving in the Sunshine State she hooked up with Hadlow.

She seemed to settle down, at first in Toowoomba, before buying a small shack at Gowrie Junction and eventually heading west in 1989.

Their integration into Roma was swift - Hadlow got a job at the local supermarket and toy shop and they enrolled my sisters into the same school the Tracy girls would attend.

Keen darts players, the Hadlows joined one of the local teams, becoming key players and holding prized positions on the committee.

Hadlow fancied himself a good bloke, reinforcing this by signing up to the region's branch of the volunteer-based State Emergency Service.

So well embraced was he, that he played Santa Clause for the town's children's Christmas party - just six months later he would murder Stacey-Ann.

I'm sure if the residents of Roma had known about the monster in their midst, he would never have been able to access children so easily.

And if they had know who he really was, it is very likely that he would never have had the chance to kill Stacey.

They say she was dead within 30 to 40 minutes of him kidnapping her.

It is not known how he got her into his car, but as soon as he did he drove her to an empty house that he and my mother planned to move into that same afternoon.

Surrounded by moving boxes, he placed Stacey on one of my mother's sheets and raped her.

After he murdered the child, he wrapped her body in the garbage bag, changed his clothes - which had blood and other fluids on them - and bundled Stacey, the sheet and other items into the back of his station wagon.

He drove out of town, dumping his victim in the bush by the creek and tossing her school bag at another site.

Later that afternoon, I arrived in town to spend time with my sisters.

He collected me from the bus stop. It was only six or so hours after he murdered Stacey, yet nothing about him set off alarm bells.

In the days before his arrest he was eager and excited about helping search for "the little girl who went missing".

All the pieces fell into place when a large group of uniformed officers and detectives arrived on my mother's doorstep, search warrant in hand.

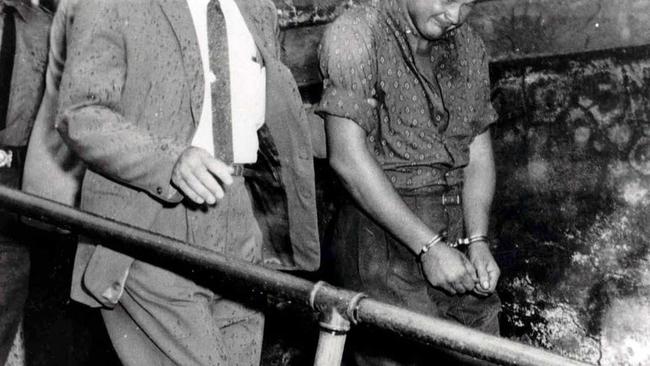

They came looking for evidence. They left with him in handcuffs, protesting his innocence, and the family station wagon on the back of a tow truck.

While Leonie refused to help police and my sisters were too young to shoulder that burden, I chose to do everything I could to make things right for Stacey and her family.

I was a witness for the prosecution at Hadlow's murder trial, providing the evidence police needed to link the darts score paper, the sheet and other items to him and Leonie.

This cost me my relationship with my mother - who has since settled in Ipswich - and damaged my relationship with my siblings. I was labelled a liar by his defence team - a slur that was repeated by the media.

This was a life-changing experience and in many ways it inspired me to follow a career in journalism.

But it still took many years for me to speak about Stacey-Ann. That reluctance to voice her story is gone now and instead, I funnel my anger and sadness over Hadlow's evil actions into advocating for an end to all forms of violence.

I never met Stacey, but I've carried her in my heart for 30 years now.

There are times when I wake in that moment between dark and dawn, thinking about how terrifying that last half hour of Stacey's life must have been.

It's hard to shake off the image of this behemoth of a man perpetrating unspeakable acts of brutality against a fragile child on that one monstrous day in May.

Stacey-Ann was just nine years and two weeks old when her time in our world ended, but the impact of her too short existence is still being felt some 30 years later.

Her life - and death - has marked her family in ways they could never have foreseen.

Her sister Libby, mum Janet and grandmother Joan could have crumbled under the weight of their tragedy, but instead they have found strength and hope in the memories of her laughter, her pranks, her singing, her intellect, her fierce independence and her lust for life.

Her friend Charlie has weathered the ups and downs of losing her best mate and the knowledge that she may never quite find another person to fill the void left by Stacey. Despite her pain, Charlie moves forward one step at a time with grace and fortitude, ensuring her own children are protected from the evil that so often walks amongst us.

Gayle, the detective who worked so hard to bring Hadlow to justice, continues her quest to hold violent people to account.

By telling Stacey's story, we hope that other Australians will be inspired to take a stand against violence.

We cannot change the ending for Stacey, for Sandra or for any of the other children, women and men lost to violence but by sharing their experiences of life and death we may just make our country a safer place.

After murder, hope is all that remains.

*For 24-hour sexual violence support call the national hotline 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or MensLine on 1800 600 636.

News Corp's Sherele Moody has multiple journalism excellence awards for her work highlighting violence in Australia. The Sunshine Coast local is also an Our Watch fellow, the founder of The RED HEART Campaign and the creator of the Australian Femicide & Child Death Map and The Memorial to Women and Children Lost to Violence.

Twitter: @sherelemoody

Facebook: www.facebook.com/sherele.moody