‘Succulent Chinese meal’ man was trail-blazer for viral fame

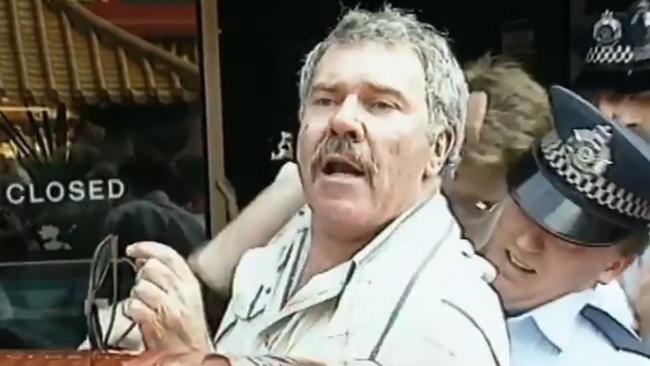

Jack Karlson was not merely a famous man, but one of the first to have achieved fame in what many older Australians still view as a strange, almost inexplicable manner.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Democracy manifest” indeed.

Jack Karlson may no longer be in a position to enjoy a succulent Chinese meal, but the ex-jail bird has certainly left us a legacy of no small importance.

It’s not incidental that his death has been recorded by the BBC, the Times of India and, perhaps most tellingly, “The Hollywood Reporter.’’

Because Karlson was not merely a famous man, but one of the first to have achieved fame in what many older Australians still view as a strange, almost inexplicable manner.

Karlson was one of the first “memeified’’ human beings on the planet.

To be memeified (a word still languishing in the “suggested words’’ category of the Collins Dictionary) is to have achieved a sort of ‘’flash fame’’, to have met with the approval, or at least the fleeting attention, of millions of people.

And Karlson and his fellow memeified travellers achieve their success in the most democratic manner possible.

Without press agents or publicity tours or even the skills of the make-up artist or costume design department, Karlson’s little one-act play of street vaudeville, which didn’t even require a written script, captured enough public attention to be rightly described 15 years after its release as a cultural phenomenon.

There are music videos and wine bottles carrying his legacy as well as a full-length documentary to be released next year. There’s even, reportedly, a racehorse called “Democracy Manifest’’

The only question lingering in the air is … why?

Twenty years since the first video was uploaded to YouTube in April of 2005 (Me at The Zoo) social media has changed the nature of fame, utterly.

Once it was the province of a selected few. Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were, just 50 years ago, one of the most famous couples on the plane.

Their celebrated film, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,’’ may have attracted millions of viewers, been nominated for 13 Academy Awards and selected for preservation by the Library of Congress.

But Liz and Dick could never have competed with “Charlie Bit My Finger’’ _ a 2007 viral video featuring a boy nibbling on his brother’s finger which had attracted 897 million views by 2022.

When Karlson’s video was posted online in 2009 the one minute and eight second piece , filmed in 1991, swiftly attracted over four million views.

How an ageing criminal protesting his arrest in a sonorous voice and describing a Chinese meal as “succulent’’ could command such attention for such a prolonged period is almost impossible to rationalise or explain.

It may be that our taste for realism in film which, experts tell us, can be traced back to the Italians and the French offering a challenge to classical Hollywood in the early 20th Century, has now spilled out beyond the control of the script writers, the directors and the producers.

Hollywood is not at risk, actors are still finding well-paying jobs and those streaming services are doing just fine.

But with the advent of social media, we the public have clearly developed a thirst for what might be termed “uber reality,’’ and we are getting it, in truck loads.

As Karlson himself said:

“Gentleman, this is democracy manifest’’