PREDATOR: The revelations that shocked a jury

It was clear the crime Leonard John Fraser was accused of was evil, but no one was prepared for what would be revealed when the jury returned the guilty verdict

Mackay

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mackay. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Read PREDATOR PART 1: KEY TO MY HEART before starting PART 2: FILTHY ANIMAL below.

THERE'S a certain amount of instinct that comes with being a journalist.

Knowing which stories are worth chasing and when something serious is developing is required on the job.

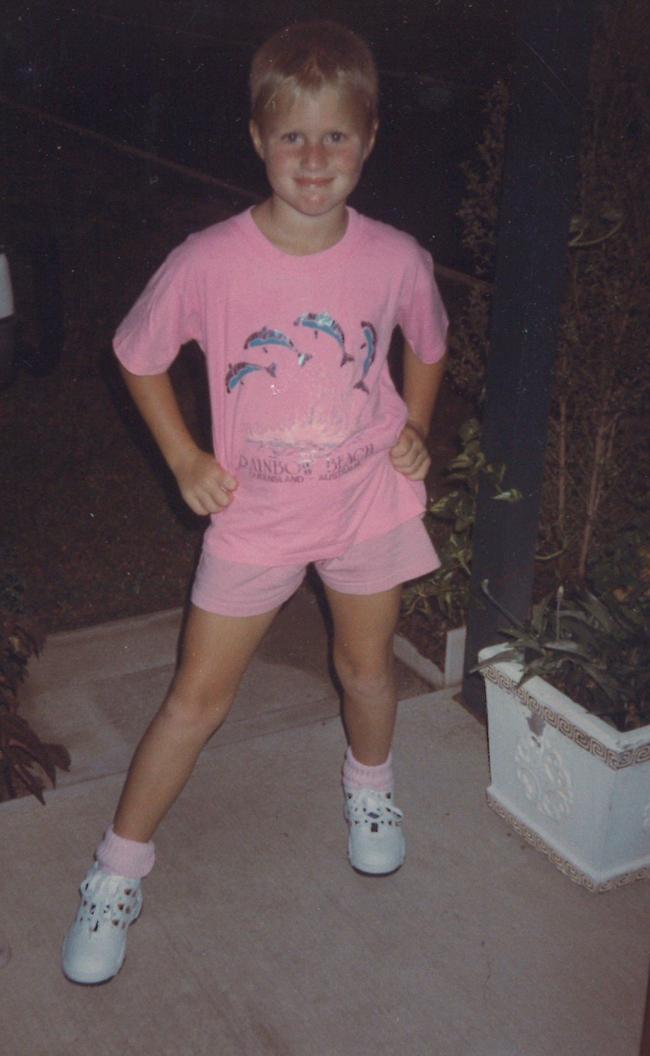

On the afternoon of April 22, 1999, The Morning Bulletin newsroom became frenzied as the first reports of Keyra Steinhardt's abduction filtered through.

He's now editor of The Morning Bulletin but in 1999 Frazer Pearce had been in Rockhampton about six months.

Frazer and his wife had moved up north from Tamworth in country New South Wales.

Although Frazer didn't initially cover Keyra's abduction or the search, as a court reporter he followed the case right through to the murder trial in Brisbane.

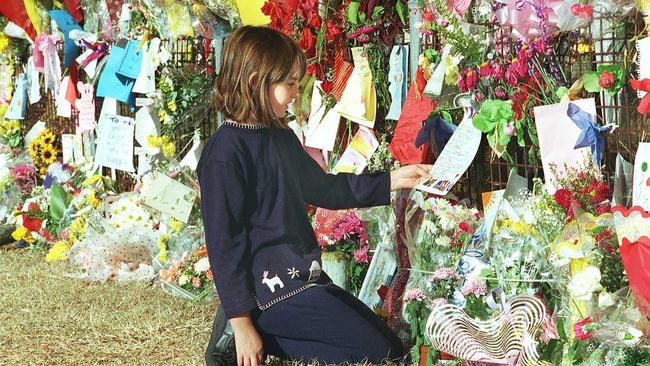

Reflecting on the desperate two-week search for Keyra, Frazer said there was an "elevated emotion" which could be felt through the whole community.

"It was a fairly animated, dynamic newsroom, and of course, always that element of 'we can't believe it's happened to us' and trying to get our heads around it and the enormity and why it had happened," he said.

Frazer was on a day off when the news broke, but the search for Keyra dominated the newsroom agenda for the next two weeks.

"Then of course, that moment they found the body, all hope had been lost."

It was clear from the start of the trial that this crime was evil, but no one was prepared for what would be revealed when the jury returned their verdict.

A KILLER'S TRAIL OF FORENSIC CLUES

Leonard John Fraser was charged with child stealing on April 22, 1999, just hours after he attacked Keyra.

He was charged with Keyra's murder after taking police to her body on May 6.

The committal hearing, where a magistrate decides if the evidence is strong enough to go to trial before a jury, were held in Rockhampton.

But the community anger was vitriolic.

John Schalch, then editor of The Morning Bulletin, wrote in an opinion piece on April 23, the day after Keyra was abducted.

It perfectly articulated the feelings which would intensify as more details about the crime became public.

"There was desolation and despair at the utter and tragic waste of such a young and innocent life," he wrote.

After Fraser was committed to stand trial, his defence team successfully argued the local community was so angry that there was no chance he'd get a fair trial in Rockhampton.

The trial was moved to Brisbane and started on August 14, 2000.

The Morning Bulletin sent Frazer down to Brisbane to cover the four-week trial.

"I remember the pressure on the first day," Frazer said. "I remember incredible pressure because you think I just don't want to blow the trial.

"You're always worried you're going to make a mistake that could cause a mistrial. But even though that wouldn't really happen, it was just a constant stress."

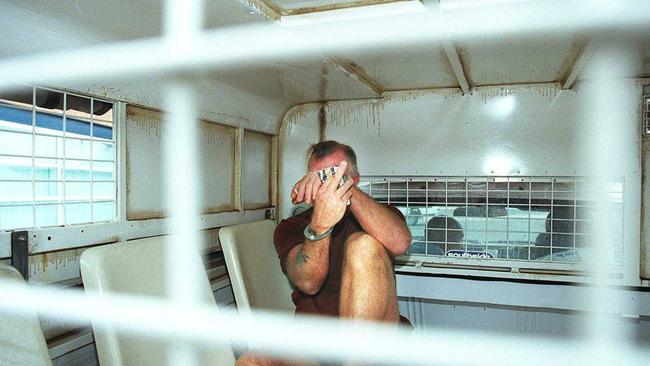

In the court room, Frazer and the other journalists were sat just metres away from the accused.

The key evidence presented through the trial included hours of interviews where Fraser spewed self-indulgent ramblings and 'hypothetical' scenarios.

Senior Sergeant Carl Burgoyne, one of the lead detectives on the case, explains he was constantly trying to misdirect the investigation.

"Fraser was an interesting person to interview, I'd describe him as pure evil. He had no remorse for his actions, protested his innocence, right from the get go," Carl said.

In court, Fraser was emotionless as the evidence was presented against him.

He had left a trail of forensic clues. There were 500 pages of evidence, 149 exhibits, 100 witnesses, 150 photos and dozens of hours of video and audio recordings.

Keyra's cause of death was never able to be determined, but her skull had been fractured and her throat cut.

Police also couldn't confirm if Keyra had been sexually assaulted, but they alleged that was the case given Fraser had a history of sexually-motivated crimes.

This theory was strengthened when Fraser revealed to detectives that he wouldn't tell them where he'd dumped Keyra until DNA evidence on her body had decomposed beyond use.

It's worth noting here that Fraser always maintained he was "not a child molester". But it's hard to judge what's fact and fiction given how many times his story changed during police questioning and later in prison.

Tiny drops of blood and a hair confirmed Keyra had been in the boot of Fraser's car, the same make and model as the one spotted speeding away from the crime scene.

There were also traces of Keyra's blood on a knife hidden in a peg basket in Fraser's house.

Of course, the most compelling evidence against Fraser was his appalling criminal record, the one thing which couldn't be revealed during the trial.

WHAT THE JURY COULDN'T KNOW

When someone is on trial in Australia, their criminal history is supressed. It's one of the fundamental elements of our justice system.

In Fraser's trial, prosecutors had to be extremely careful when eyewitness Ben Robson took the stand.

Ben drove past Fraser at the scene. Ben recognised him as a former inmate at Etna Creek prison north of Rockhampton.

The problem was how to explain in court why Ben had recognised Fraser, without also revealing he had been in prison.

It almost slipped out during cross-examination, and those in the know held their breath.

But the judge decided it wasn't obvious enough to sway the jury.

There was, however, a real concern they wouldn't convict.

Frazer said the main debate focused on the timeframe on the afternoon of April 22 and how Fraser managed to get from the attack site in Dean St, to Callaghan Park on the riverbank, to Rockhampton Yeppoon Rd where Keyra was eventually found.

In the end, it was close and the jury had to be put up in a hotel overnight as they debated the outcome.

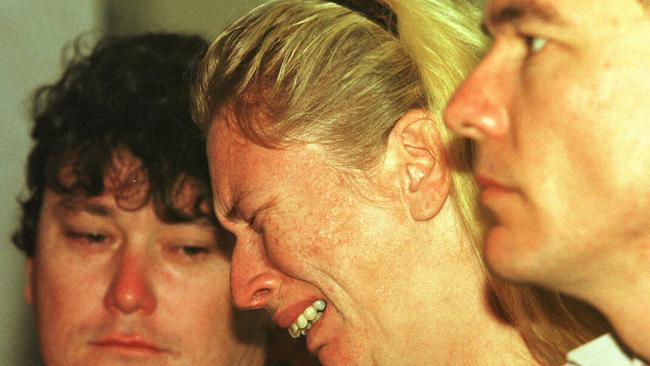

One word, guilty, brought gasps of relief, excitement and joy from the courtroom's public gallery.

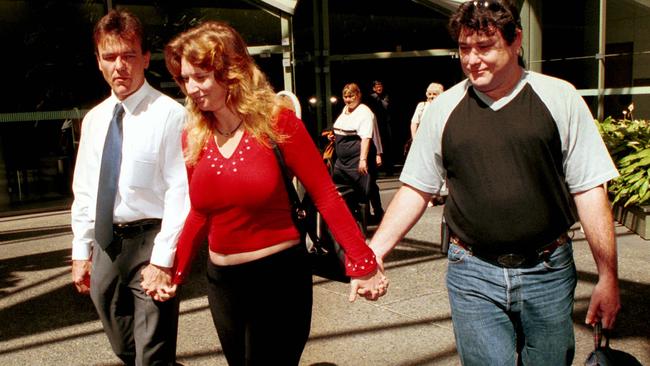

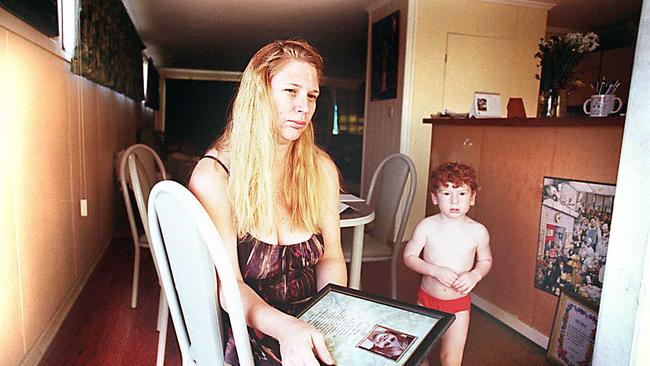

Keyra's mum, Treasa Steinhardt, had been first to give evidence and stoically sat through each day of the trial.

"After the fourth week, being there for that long and then finding out the verdict of it, I was joyful," she said. "Apparently, he gave us a dirty look, but I was excited. I was just relieved he was going to jail and never coming out. That she (Keyra) actually got him in there."

Treasa has shared with us a letter she wrote to herself during the trial. Letters were like journals for Treasa, who would also write to Keyra even after she died.

This letter was dated Monday, August, 21, 2000.

For some reason I didn't want anyone around me, I must have went to the toilet five times to cry quietly to myself. I felt empty and lost and no one could help me, it had nothing to do with the court room or hearing anything. I just wanted to cry when I felt like crying.

I'm crying because it's not fair - I always said why my daughter?

I'm scared to look at anyone or smile at anyone just in case it hurt my daughter's case. I cry again as I feel this may be the reason why I cry. I feel I don't wish to lose her case for my stupid action.

For Frazer, the strongest memories of the trial are the moments when members of the jury started to hear about Fraser's shocking criminal history.

"One of those moments I will never forget in my life will be the guilty verdict and then the prosecutor reading through Fraser's previous criminal history and the incredible relief in about three or four members of the jury, who were visibly moved with just displaying an incredible relief, a mixture of relief I think and anger," he said.

"They were obviously the people who had difficulty, because of all the circumstantial evidence, in finding a guilty verdict."

MAKING A MURDERER: LEONARD JOHN FRASER'S LIFE OF VIOLENCE

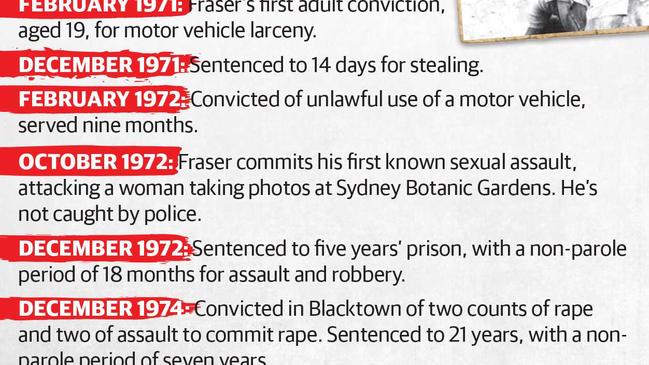

Fraser was born in the North Queensland town of Ingham in 1951, but his family moved to Sydney when he was six.

At 14, he dropped out of school and was soon convicted of his first criminal offences, sentenced to 12 months in a Gosford boys home for stealing.

Throughout his teenager years, Fraser continued to appear before court until he committed his first known sexual assault.

It was October 1972. Fraser attacked a 37-year-old French tourist as she took photos in Sydney Botanic Gardens.

He struck her from behind and brutally beat and raped her.

The woman's injuries included a fractured cheekbone.

She was a mother of two young children, visiting Australia with her husband for a conference.

But Fraser wasn't caught by police. In fact, they wouldn't find the culprit for two years.

Between October 1972 and June 1974, Fraser was in and out of prison on robbery and dishonesty charges before setting out on a sexual assault rampage where he raped one woman and attempted to assault two more.

As police interviewed Fraser about those attacks, he confessed to raping the French tourist back in 1972.

In December 1974, Fraser was sentenced to 21 years in prison for those attacks.

During this time, a prison psychiatric examination found Fraser to be a psychopath with no impulse control. He was 23 years old.

Despite this report and the violent assaults he was convicted of, Fraser served just seven years of the 21 he was sentenced to before being released on parole.

Fraser returned to North Queensland where he broke into a house in Mackay and was sentenced to two months' jail for the aggravated assault of the woman living there.

From 1982 to 1985 Fraser had a relationship with a Mackay woman. The pair had a daughter together, but there's no public record of what happened to her or her mother.

But Fraser could only lead a normal life for so long, soon returning to his predatory ways.

He stalked a woman during her beach walks at Shoal Point near Mackay for several days before brutally raping her and leaving her for dead in the sand dunes.

In handing down a sentence of 12 years' jail, Justice Des Derrington said Fraser was a dangerous and violent rapist who failed to realise the enormity of the cruel and cowardly crimes.

He told Fraser his victims would consider him "the equivalent of a filthy animal".

This time, Fraser wasn't getting out early. He served every second of his sentence at Etna Creek just north of Rockhampton.

But the guards knew even as he left that it was a matter of when, not if, they would see him again.

Fraser was released in January 1997, when he lived in the coastal town of Yeppoon and then the tiny former gold mining town of Mount Morgan.

By 1998, Fraser was settled in Rockhampton and a familiar face among the city's underbelly and he started preparing to attack again.

'WHEN KEYRA DIED, I DIED'

Fraser's last day of freedom had been April 22, 1999. The day he killed Keyra.

He was sentenced to life in prison for her murder.

During sentencing, Treasa read out a victim impact statement. She's allowed us to re-print parts of it here:

Keyra - she has a big heart, if you didn't know her by now you will. She always helped others, everyone in our street knew of her. She always had to go to school just after 8am in the morning. She'd say hello to everyone and play. She even got to manage the afternoon school bus. Keyra has done a lot in her short life but I always thought she was going to be here with me. My life is over, what can I say. When Keyra died, I died. It's so hard to tell someone what we are going through unless they've been there. No sleep, bad dreams, crying every night, yelling at everyone, blaming everyone, not eating, the house is a mess, bills pile up. These are only some things. She was my mate: friend and daughter, number one. Keyra - key to my heart.

THE TRAUMA OF LIFE AFTER DEATH

While that statement illustrates how Treasa was feeling in the immediate aftermath of the trial, she also spoke to The Morning Bulletin about what happened when the trial, the quest for justice, ended.

"I don't know what I would have done if they never got Keyra back," she said. "I went back to work, I had to go back to work to keep myself busy."

Treasa and Blair had been engaged but, she explained, this was mostly so Keyra could have the same last name as her little brother Connor.

"When she was killed I even said it to all of my family: 'well, what's the use of being married'," Treasa said.

"So, we weren't going to get married. But because Rockhampton heard about us to be married, it sort of threw us into that and it sort of made me forget and focus on something else. So we got married. That lasted one year, not even a year."

When the trial was over, Treasa had to return to a sense of normal life. Although it was obvious things could never be the same.

"I would come home, and I didn't feel like doing anything," she said. "I didn't want to be a mum. I didn't want to give Connor any attention. I just felt that I'm not a mum anymore. So, he suffered.

"I took him out to the allotment where they found Keyra and I thought about killing ourselves, him and me. And he was laying on my lap and I looked at him and I couldn't do it because he was so innocent and it was selfish and unfair that I would take his life just for me to be with my daughter. So, I said that I was leaving."

Treasa left Connor with his father Blair and moved out of Rockhampton. But, the depression and suicidal thoughts lingered with her. At the end of this series, we're going to explore how she re-built her life and eventually found peace with being a mother to Connor again.

"What really hurts is that someone took her life for no reason," she said. "If she was to die of car accident, cancer, I can accept it. That is a reason, an explanation. But no human has a right to take another human's life."

There is a reason Keyra died though, and it's an uncomfortable truth. Keyra died because the legal system made a terrible mistake in letting a predator out of prison.

But Keyra wasn't the only person failed by our legal system, a number of other women were too. At home in Rockhampton, four other women were missing and it was beginning to look like a serial killer had been at work.

PREDATOR PART 3: UNLIKELY HEROES will be released next Monday.

ABOUT PREDATOR:

This series is based on interviews with Treasa Steinhardt, Snr Sgt Carl Burgoyne, Eddie Cowie, Frazer Pearce and Allan Quinn. Michelle Gately also reviewed original Morning Bulletin reports (with thanks to the History Centre at Rockhampton Library), interview transcripts (provided by Treasa Steinhardt), and court documents.