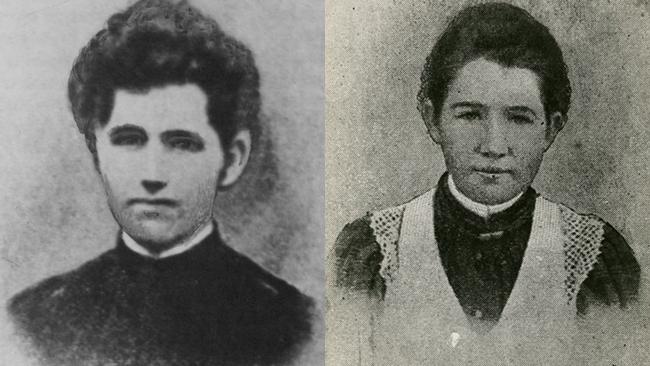

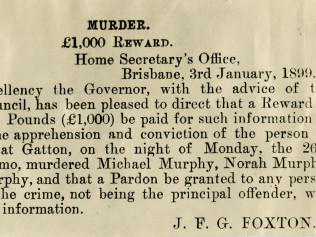

Cold case murder: Deaths of Michael, Norah and Ellen Murphy still a mystery 120 years on

TWO sisters raped and bashed to death, their brother shot. Did the brother-in-law who found their bodies know more about the crime? Or was it a revenge attack by a convicted criminal?

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“IS it unusual,” William McNeil began, “for them to be away so long?”

It was December 27, 1898, and William was at the breakfast table with his in-laws.

Michael, Norah and Ellen, his wife’s brother and sisters, had taken a horse and buggy for the 10km trek into the Queensland town of Gatton the night before.

There’d been a dance on in town and the girls had wanted to go. It wasn’t unusual for a country dance to go all night but the sun had risen and work had started on the Murphy family’s Tent Hill farm. They should have been home.

They’d taken William’s cart, an unreliable contraption that had confounded three blacksmiths. The horse they’d taken was slow and deaf.

“It might not be too safe,” William commented. He wondered whether the buggy, with its wobbly wheel, had broken down.

“If one of them had walked from Gatton, they could be here by this time.”

They talked about what could have gone wrong. But by 8am, concern had turned to alarm.

“Michael and the girls didn’t come home yet,” he’d told his wife Polly before breakfast. A mother to his two children, Polly was partially paralysed and had never fully recovered from childbirth.

She and the children lived with her parents. William stayed on weekends when he was home from work.

“Really? Are you joking?” she asked him.

He saddled a horse and headed for Gatton.

Outback mysteries: Answers shrouded in Australia's red dust

Wanted posters: Bushranger turns tables on colonial rulers

He followed the road for several kilometres, stopping in at the creamery to ask whether they’d seen the cart go past. They hadn’t.

Another several kilometres on he spotted wheel tracks turning into a paddock on the Moran property. The tracks were from his cart — he could see the marks from the wobbly wheel.

Why had they turned off the road?

He followed the tracks into the paddock. He’d expected to see a road leading to a house.

But there was nothing.

The tracks took him down a ridge before leading him to the right, where one paddock met the next.

He went on foot from there, leading his horse for another kilometre.

That’s where he found them.

It had looked like a pile of clothes at first, the cart and horse nearby.

The horse was lying down. Soon he’d see it was dead.

The pile of clothes was Norah.

She was lying on her right cheek, her feet pointed to the west. He knew she was dead from the ants on her face.

William would later tell police he’d found his brother and sisters-in-law dead.

He didn’t use the word ‘murdered’, even though Norah, left on a neatly-spread blanket, had her hands tied behind her back and a leather strap secured tightly around her neck.

Her head was bashed in, her skull exposed.

A 5cm cut made its way down the left-hand-side of her face.

She was near-naked. She’d been raped. Her killer had torn at her clothes, at her skin with his fingernails.

Michael and Ellen were nearby, their bodies placed back to back. Michael had been shot and bashed, his skull caved in from the brutal assault.

His sister had been bashed and raped. Scratches covered her legs.

They lay together, Ellen’s hands bound with her handkerchief.

William didn’t approach Michael and Ellen. He jumped on his horse and kicked it into a canter, heading for Gatton.

He stopped at the Gilbert Hotel and asked after the police sergeant.

His brother and sisters-in-law were lying dead in the Moran paddock, he explained. A man told him where to find the sergeant and he continued on.

Several locals followed William and Sergeant William Arrell back down the road towards Tent Hill.

He left them at the Moran property and continued on to the Murphy place.

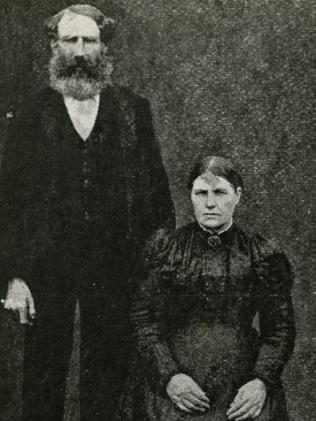

It was 10am when he rode up to the farmhouse. Their mother, Mary, met him at the door.

“Have you seen the children? Are they coming?” she asked.

He answered the second question. “No,” he told her calmly.

“Why?” she asked.

“They were dead and murdered in a paddock up at Gatton, with their hands tied behind their backs and their heads bashed in.”

She looked at him in shock.

She screamed and cried. “Oh my God, my poor children!” she sobbed.

She screamed their names. Michael. Norah. Ellen. She cried out for them over and over.

They saddled horses and Mary rode with her son-in-law to see the bodies of the children.

They arrived to find the police sergeant gone. He’d left two men guarding the bodies while he rode for the telegraph office. They’d need help from Brisbane.

It was the beginning of a series of police blunders that would help ensure the killer was never caught.

Sgt Arrell returned to a crowd of 40 people trampling the crime scene. One handed him one of the murder weapons — a piece of bloodied wood used to bludgeon the siblings.

Mary Murphy was sobbing over the bodies of her children, begging to be allowed to take them away from the paddock where they’d been killed.

The sergeant wanted the Murphy siblings left in place until the medical examiner arrived, but eventually succumbed to the wishes of their grieving mother.

When Dr Von Lossberg arrived at 4pm, he discovered the bodies had been taken to the pub, where two local ladies had undressed them and laid them out.

His inspection was cursory only.

He missed the bullet lodged in Michael’s skull, discovered later when the chief inspector of police ordered the bodies be resumed and a second autopsy conducted.

Von Lossberg would later claim he was suffering from blood poisoning. That the police had rushed him. That he ordered the bodies not be buried so he could conduct a more thorough examination.

A funeral for the Murphy siblings was held on December 28, without a burial order from the doctor.

It was the largest funeral ever seen in a country area.

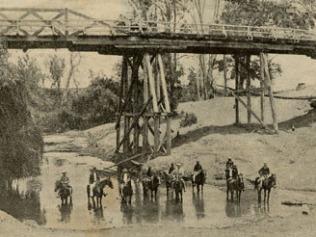

About 1000 people came to farewell the trio, with row upon row of horses and carts lined up along the cemetery fence.

They watched as Mary sobbed bitterly for her children.

Handwritten investigation logs show police called for the assistance of Aboriginal trackers the day Michael, Norah and Ellen’s bodies were found.

“Forwarding two black boys to Gatton,” was the only entry for December 27.

Had 40 people not tramped through the crime scene, their expert skills may have assisted police. But it was useless.

The Muphys were questioned extensively. Did they have any enemies? Had they received any threats? Had they upset anybody? Did the girls have “sweethearts”? Jilted lovers?

They watched William through narrowed, suspicious eyes.

His wife Polly was questioned. Had he gotten up during the night? Why did he sleep in his clothes? Had he come to bed with his boots on?

Of course not, she told them. He slept in his clothes so he could get up if the baby woke.

THE SUSPECTS

Thomas Ryan

Suspicion fell on Thomas Ryan early on, a labourer and drover who had courted Polly for years before her marriage to William.

He’d been confronted by Mary, several years earlier, after she put a stop to the blossoming relationship.

Thomas was not good enough for her daughter. He was too fond of a drink.

He came to police attention as early as December 28, when an entry in the log recorded “re Ryan family (character of)”. A reference to police taking a statement from Thomas was made the following day.

When questioned by police, he denied saying he would have his revenge on Mary for robbing him of his sweetheart.

He told them he was at home with his parents in Gatton on the night of the murders. His mother would later swear that was true.

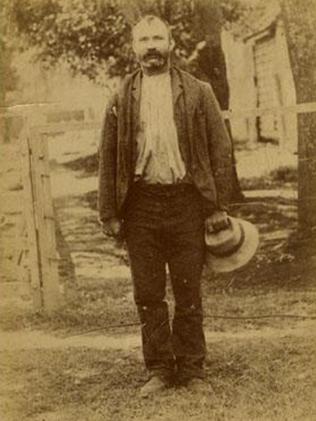

Richard Burgess

On November 30, 1898, Richard Burgess was released from St Helena Island prison in Moreton Bay.

He’d been jailed for attacking an elderly woman, taking a bullet in the arm from her son who came to her rescue.

It was not his first time in jail. He’d been convicted on charges of attacking women no less than 13 times.

With a tent and swag, Richard had been making his way across Queensland.

He matched the description of a bearded man seen near Moran’s paddock on the night of the 26th.

Police initially believed he was within 20 miles of Gatton the following day.

He’d put up a great fight when police came to arrest him on January 8.

“It is not known what evidence the police have, but outsiders do not attach much importance to the arrest,” one newspaper report read.

And they were right. Days later, the charges were dropped.

Further investigations had given Burgess a solid alibi. He wasn’t in the area at the time of the murders.

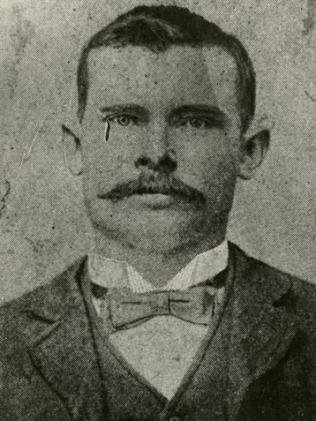

William McNeil

Police questioned William closely about his movements on the night of the 26th and about his movements on the morning of the 27th.

Why had he said the Murphys were “lying dead” in the paddock? Why not murdered?

Why had he gone to bed in his clothes?

Why had he paid for the funerals when the Murphys had the money to do it themselves?

They questioned his wife, his mother-in-law.

Mary became furious with police over their interest in her son-in-law. They became exasperated with her.

A police magistrate would later reprimand her for the evidence she begrudgingly gave at the inquest into her children’s deaths.

“I think I am justified before closing this inquiry in remarking that I am greatly astonished at the extreme apathy of the blood relations of the victims,” he said.

“They appear to have done nothing.

“They had a number of horses at the farm, but these were not offered to the police.

“Their evidence, too, has been most unsatisfactory, and also very contradictory, especially with regard to the horses which were in the vicinity of the farm on the night of the murder.

“The relatives of the deceased appear to have treated the whole business as ‘kismet’ and acted as if they wished to have the whole matter buried in oblivion.”

Polly was also called to give evidence before the inquiry.

She struggled under examination from Inspector Frederic Urquhart.

“Can you really swear that your husband did not go out?” he asked.

“An oath, you know, is not taken for nothing.”

The minutes ticked by and Polly said nothing.

“Did you hear my question Mrs McNeil?” he asked.

Polly told him she had.

“Have you no answer?” he continued.

“No,” she replied.

He tried again.

And again.

She turned her head from him.

“I would not press her anymore,” the police magistrate eventually said.

The townspeople began to suspect William too.

When he returned from a trip to Toowoomba in January, he discovered many had already convicted him of the murders.

Locals refused to speak to him. The women in a boarding house where he stayed would not serve him.

“The police ought to arrest me if they have any suspicions I committed the crime,” he announced.

Mary had no suspicions that her son-in-law was responsible. And she made it clear to investigating police.

“They are a damn lot of traitors,” she railed.

“May God grant they have some troubles themselves before they die.”

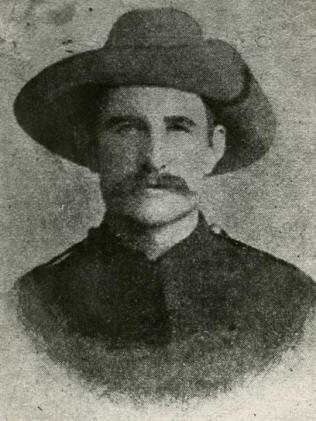

Thomas Day

Thomas Day, 22, had arrived in town in December, taking on a job as the “butcher’s boy”.

By January, he was on his way. He didn’t like the food.

He enlisted in the military and later deserted. He was never heard from again.

He was never properly questioned, to the fury of the Police Commissioner.

Some locals, including the Murphys, believed only a “stranger” to town could have carried out the murders. To them, Thomas was a stranger who should have been questioned.

More than 70 years later, a Brunswick Heads man would make a startling deathbed confession, claiming to be the butcher’s boy and the person responsible for the brutal murders of Michael, Norah and Ellen.

He claimed to have left the gun in a tree stump, telling two friends where it would be found.

Police looked into his story but were not convinced. No gun was recovered.

A gang

Author and researcher Stephanie Bennett believes a gang of youths — led by a man with a hatred for Michael Murphy — carried out the murders.

She believes the man, a career criminal who used more than 200 aliases, met Michael when he was sent to Longreach as a special constable to keep the peace between shearers and pastoralists.

Michael recognised the man as a criminal and announced him as such in front of a crowd of men.

He was arrested and jailed for a year.

He told fellow inmates he would have his revenge once released.

“It’s all there, in the records,” she said in one interview.

True Crime Australia book extracts: Bigwig | Eugenia | Stalked: The Human Target | Noose

- This is an edited version of a story first published in November 2014