Outback mysteries: Answers shrouded in Australia’s red dust

Australians and tourists alike are drawn to the grandeur and mystery of the Australian outback, but when disaster — or a killer — strikes our vast land does not give up its secrets easily.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Peter Falconio is probably the name that first comes to mind when Australians think of outback mysteries.

The disappearance of the British backpacker after he and girlfriend Joanne Lees had the horrific misfortune to encounter Bradley John Murdoch on the Stuart Highway in 2001 makes headlines to this day.

Mystery letter: Is this what really happened to Falconio?

But the location of Falconio’s body is just one of the many secrets still hidden in the dust of our vast and often unforgiving land.

CHRISTOPHER LIMERICK

Petty thief Kumanjayi Limerick — known as Christopher — was just 20 when his badly decomposed body was found at the bottom of Nobles Nob, an open cut mine near Tennant Creek.

And while his 2000 death remains a mystery, it was back in the news this year with the death of another man — former All Black Keith Murdoch.

Murdoch sought obscurity in the Australian outback after becoming the only New Zealand rugby international to be sent home from a tour in disgrace after punching a security guard in Cardiff in 1972.

He was shattered by the incident, and over the years gave a surly send-off to any reporter that had the temerity to track him down.

But he couldn’t avoid the limelight after failing to appear at the 2001 inquest into Limerick’s death and being sought by Northern Territory police as a critical witness.

Murdoch was one of the last people to see the Aboriginal man alive after catching him breaking into his home, not for the first time. A neighbour gave evidence of hearing a confrontation on October 6, 2000, and threats from “the Kiwi bloke”.

But when he was eventually tracked down and did give evidence, Murdoch told the coroner he could not recall the incident at all. Meanwhile, in a rare media interview, he denied there was anything suspicious about his own disappearance from Tennant Creek as he was travelling to find work.

Limerick went missing shortly after the claimed confrontation and his body was not found until three weeks later, after a witness came forward saying he had seen someone matching his description at the mine on October 7 or 8, but hadn’t stopped to help.

The coroner did not believe Limerick could have reached the mine site, about 15km out of town, on his own and referred the case back to police.

“I believe the crimes of unlawful assault on the deceased and deprivation of his liberty may have been committed in connection with death,” he said.

But the following year police said they had completed their investigation with no charges laid.

Murdoch, who was never directly accused of any crime, slipped out of the public eye again until his death, aged 74, made headlines in March this year.

What really happened to Christopher Limerick, and how he came to die at the mine site, disorientated and dehydrated, remains unknown.

TANJA EBERT

In August this year, police in South Australia offered a $200,000 reward for information leading to the recovery of Tanja Ebert’s body.

The mother of two young sons had been reported missing a year earlier, and in a shocking development just days later her husband Michael Burdon, 41, killed himself while police were at their Oulnina Park Station property investigating.

Detectives were convinced her body was hidden somewhere at the remote property, The Advertiser reported in August, and that her husband may have discussed the death of his wife with family or friends.

“We suspect there (is a) person or people who do know the circumstance of Tanja’s death,” Detective Sergeant Paul Ward told the paper.

“There are aspects of the investigation that have come to light that lead us to believe that.

“At times people protect others reputation within the community. What we would do is ask those people to put that aside.”

Mr Burdon told police he last saw his 23-year-old wife on August 8, 2017 when she left the family car at Roseworthy after an argument as they headed home from a family trip to Adelaide — an account they have since rejected.

She was reported missing two days later, and on August 16 — just hours before Michael killed himself — police said they were treating her disappearance as a murder investigation.

Searches of the 410 square km property have failed to find Ms Ebert, who was originally from Germany, but police have said “everything leads us to believe she is there”.

Ms Ebert moved to the property, some 360km north of Adelaide, after meeting her future husband while travelling around Australia in 2012, but by the time of her death she was said to be unhappy in her marriage and to have spoken about leaving.

Offering the reward, police said Ms Ebert’s husband remained the only suspect in relation to her suspected murder.

Police have urged anyone with information to contact Crimestoppers online at crimestopperssa.com.au or by calling 1800 333 000.

“Police want to be in a position to give her young children answers about what happened to their mother,” a spokesperson told True Crime Australia.

RAYMOND AND JENNIE KEHLET

“IT’S about the most remote area you can find on the planet,” West Australian Police Commissioner Chris Dawson said of the outback site that saw the death of Raymond Kehlet and the disappearance of his wife Jennie.

In March 2015, the couple, both in their late 40s, had set up camp about 26km north of Sandstone, in the state’s north, on a prospecting trip.

Authorities were only alerted to the fact that they were missing about a week after they were last seen, when their emaciated dog wandered alone into the Sandstone caravan park.

On April 8, Raymond’s body was found at the bottom of a mineshaft about 1.8km from their well-equipped and intact campsite — but despite an extensive air and land search there has been no trace of mother-of-three Jennie since.

In October last year, the WA Government offered a $250,000 reward for information leading to the conviction of the person or persons responsible for Raymond’s death and Jennie’s disappearance.

“The death of Ray is being regarded as a suspicious death and homicide squad are involved. You can join those dots together,” Mr Dawson said at the time.

The couple’s family issued a statement hoping the reward would “bring together the missing pieces of our family’s tragedy”.

“The last two years have seen our family caught in an agonising and exhausting limbo, desperate for answers and for closure,” it said.

Police have told True Crime Australia there have been no new developments since the reward was offered.

PADDY MORIARTY

The disappearance of Paddy Moriarty and his dog has exposed long-running tensions between the handful of residents in Larrimah, a speck on the map about five hours south of Darwin.

Police believe the 70-year-old met with foul play, and followers of the case, which has received international coverage, are keenly awaiting Coroner Greg Cavanagh’s findings after an inquest commenced in June.

Paddy was last seen on December 16, 2017 leaving Larrimah’s Pink Panther Hotel, which he visited every afternoon, on his quad bike with his dog.

The inquest heard of a long-running feud between him and town pie cook Fran Hodgetts, and colourfully-worded verbal clashes with both her and her gardener Owen Laurie, both of whom denied any involvement in his disappearance.

The coroner was told of one incident where Ms Hodgetts threw a dead kangaroo over Mr Moriarty’s fence, only for him to then place it under her kitchen window, The Australian reported.

The NT News said the inquest also heard Ms Hodgetts had made a string of complaints about Paddy to police, dating back as far as 2010 — including theft and petty vandalism — but there was no evidence to support the claims.

Mr Laurie said a comment he’d made about “the first murder in Larrimah” if anyone messed with his garden was a joke.

And Ms Hodgetts insisted neither of them knew what happened to Paddy. “I just want the f---ing thing to be over,” she said. “How do you think I feel? How can I make pies with all this going on?”

Former barman Richard Simpson was also asked if he’d had anything to do with the disappearance. “I’m too tired to be doing nonsense like that, and besides, Paddy was my mate,” he said.

Meanwhile Detective Sergeant Matt Allen said almost 100 statements had been taken as part of the investigation and Paddy’s body would have been found “if he was above ground”.

No date has yet been set for the inquest to resume.

MISSING: The people who vanished into thin air in the NT

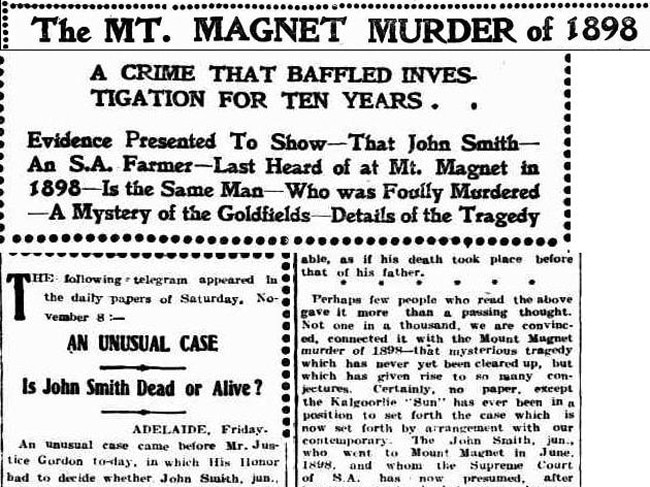

MOUNT MAGNET MINE MURDER

One of the nation’s oldest outback mysteries centres on a gruesome discovery at the Mount Magnet mine in Western Australia.

In 1908, the Sunday Times laid out for it’s readers the evidence it believed finally identified the victim of an “atrocious crime” — the murder and dismembering of a man whose body parts were found in several mine shafts in the state’s goldfields 10 years before.

Whether the theory — originally put forward by the Kalgoorlie Sun — was correct is impossible to say, and no one was ever brought to justice, but even after all these years the case makes for intriguing reading.

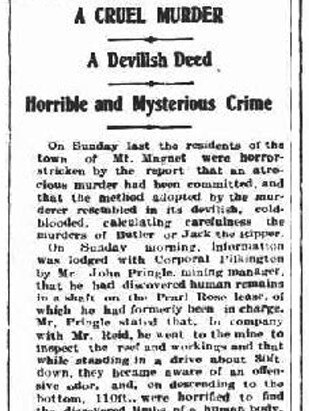

As part of it’s report, The Times reminded readers of the horrors of the killing by reprinting contemporaneous reports from the Mt Magnet Miner under the heading: A Cruel Murder; A Devilish Deed, Horrible and Mysterious Crime.

Comparing the 1898 atrocity to the work of Jack the Ripper, the Miner told how two men checking a mine had noticed an offensive odour and on “descending to the bottom, 110ft, were horrified to find the dissevered limbs of a human body”.

With police called, the search began for other body parts, and at a shaft some way away another strong odour was apparent — this time leading to the discovery of a head and part of a body.

Jessica Barratt, who has researched the case extensively for history blog The Dusty Box, says the final pieces of the body were not found until 1902, when a prospector came across them in another mine shaft, tied in a rotting chaff bag.

An inquest went ahead before then, and established the victim had been in the prime of life “stoutly and strongly built”.

But his “skull had been crushed in by a violent blow”, with “a great gaping hole in the head over the left temple” and “the limbs had been carefully dismembered with almost surgical accuracy”.

The jury could only determine that a man, unknown, had been murdered by person or persons unknown, on a date unknown.

Ten year’s later attention was drawn to a case in Adelaide to determine if a farmer, John Smith, from Narracoorte, was dead or alive for the purposes of settling his estate.

Smith had headed to Mount Magnet in June 1898 and “had disappeared from mortal ken”. The Supreme Court concluded he was dead.

Comparing the descriptions of the mystery man and John Smith, the Times reported a match — “Even from the scanty details furnished at the inquest it was clear that the man who had vanished and the man who had been found down a shaft were of an age, much of a physique, much of a height”.

A member of Smith’s family accepted the theory, though Smith’s mother clung to hope. “The description we are sorry to think is only too sure,” the relative wrote. “We were forced to the conclusion, many years ago, that he had never lived long in the West.”

The suggestion was he was murdered for his money.

But even the Times accepted they couldn’t prove the connection: “We leave it to the public to arrive at their verdict on the case we have sought to make out.”

Originally published as Outback mysteries: Answers shrouded in Australia’s red dust