Placed into a loving home at birth Kaydence Mills had every chance of a bright future. But when the state ordered the then-toddler be returned to an abusive home, her death was sealed.

Readers are advised this article includes the name and image of a person who has died.

• National helplines: 13YARN and 1800RESPECT

Removed from the loving foster carer who had raised her from birth and returned to her biological mother, a little girl lay on a red couch with a white floral sheet pulled up to her chest as if she were sleeping.

However a mix of old and recent bruises covering the face of two-year-old Kaydence Hazel Mills told a more sinister story, and soon she’d be wrapped in black plastic bags and discarded like the garbage they should have contained.

It’s not known exactly how many weeks the toddler lived after being released by the Department of Child Safety in late 2016 or how she was killed by her stepfather Tane Desatge.

But evidence shows she did die alone in a living room sometime between February 2017 when she was seen being moved into a Chinchilla rental, and early May, when her mum, Sinitta Tammy Dawita booked a train ticket for herself and her other children but not Kaydence.

The forgotten toddler was missing for years before anyone began looking for her in late 2019.

A six month long covert police operation led to Kaydence’s remains being excavated from the Chinchilla Weir in March 2020, after undercover officers got Desatge to flip on his story and take them to where she was buried.

There, she lay in the unmarked grave among gumtrees on the Condamine River, discarded and broken, for as many years as she’d been alive.

A court would later hear that the day after Kaydence died from injuries caused by the 44-year-old sadistic alcoholic, her body, curled up in the fetal position, remained on the dirt floor of an empty garden shed, while he played the pokies and went shopping to cover his tracks.

A heavily pregnant Ms Dawita helped the father of 11 cover up Kaydence’s murder.

The pair meticulously wrapped her body in several layers of black garbage bags before moving the body and burying her under the guise of a camping trip.

Kaydence’s abuse and neglect began days after the young family relocated 1359km away from her mother’s friends and family in Tully to Chinchilla, two hours west of Toowoomba.

From a loving home to hell on earth

During the murder trial of Kaydence’s birth mother and stepfather, her loving foster mother, Sally Pearson, was the first Crown witness called, her voice wavering with grief from the first word.

Through tears, the married Innisfail woman said one exchange with Ms Dawita, not long before she saw Kaydence for the last time, stood out in her mind.

“When I dropped her back at the hotel (for a visit)… I said ‘can you hold Kaydence and just make sure’, because Kaydence was attached to me right, and ‘just hold her and cuddle her and console her while I leave’,” she said.

“And then Kaydence come (sic) to the (car) window and she’s screaming – wouldn’t you hold your baby?”

Ms Pearson said the last time she saw Kaydence she urged Ms Dawita to reach out if there was ever anything she needed.

“I was trying to call Kaydence for her (last) birthday but then I got a message (from Ms Dawita)… she just said, ‘sorry I missed your call, I was camping, Kaydence is good’,” she recalled.

“That’s the last time I heard from (her).”

Ms Pearson’s mother Lee-Ann Davis-Collier told the court Kaydence became her beloved granddaughter.

She recalled bumping into the family by chance at Kmart in Innisfail not long after Kaydence was removed from her daughter’s care.

“She was very thin, thinner than what I was used to seeing her,” she said.

“It wasn’t the baby that I knew.”

Ms Davis-Collier said she would never forget the look on Kaydence’s face when she tried to run into her arms but was stopped by Dawita and moved along.

“She was just sad. It was heartbreaking for me,” she said.

Slipped through the cracks

Questions emerged from the trial about how a child formerly in state care could be placed in a household with a domestically violent man, who was red-flagged in the child’s file.

Why a child safety officer took so long to follow up on Kaydence’s new home and check on her welfare was also unexplained.

Kaydence’s disappearance only attracted the attention of authorities in September 2019 after her eldest sister spoke about her to a primary school guidance counsellor.

In November 2016, Ms Dawita, 32, undertook countless supervised and unsupervised visits with her three girls, including Kaydence, before the department deemed her fit to regain custody.

During the murder trial in Toowoomba Supreme Court, Kaydence’s first child safety case worker said he raised concerns about Desatge’s criminal history because of the domestic violence he had committed against Ms Dawita.

Desatge had few interactions with Ms Dawita’s caseworkers.

The court was told the department attended the family’s Chinchilla home in November 2018, which was sparked by Desatge beating Ms Dawita after dragging her out of bed by her hair while she was breastfeeding.

Ms Dawita told the Child Safety officer Kaydence wasn’t home because she was living with an aunt in Brisbane, however she didn’t provide the family member’s name, address, or phone number.

No one followed up on Kaydence’s whereabouts.

She had already been dead for more than a year.

Child safety employee speaks out

A former employee of the department with first-hand knowledge of the case said there were some failings in the system, however 95 per cent of the time the department got it right.

“If they didn’t, there would be 100 more Kaydences, 100 more Mason Lees,” he said.

He said it was normal procedure for the department not to physically check in on every child once their case was closed.

“There were no reports, no one was complaining, so the department had no reason to visit,” he said.

Kaydence’s biological father, Robert Mills, told The Courier-Mail he made multiple reports to Child Safety about his concerns for Kaydence’s welfare, but he believed they disregarded his complaints because of his criminal history.

The former employee agreed the department didn’t take Mr Mills’ concerns seriously because of his character and how often parents rang the department reporting issues they had with contacting their child.

“That happens in a lot of custody disputes,” he said.

“One in every couple of hundred calls (on a weekly, sometimes daily, basis) is a real call, but you have to sift through those.”

He said a missing person report should have been logged for Kaydence in October 2018 following the DV incident when the Queensland Police Service and Child Safety visited the home.

“It was a failing on both of the department’s behalf,” he said.

“No one knew where Kaydence was then and she wasn’t at the home when police attended so there was a breakdown in the record collection.”

He said the Child Safety officers who attended the home were relatively new and had limited experience.

The former Child Safety worker said despite minor failings of the departments, the real failure was society as a whole.

“When a child dies, the thing to remember is there can be system failings at the back end of that but along the way, there are filings from society in Kaydence’s case, and in Mason Lee’s case, and even in the case of two (Logan) girls who died in the car.

“There were failings by society, the family in general, and broader society not to actually raise the alarm sooner.

“More children would be safer if everyone had the bravery… (to) call up and say ‘hey I’m worried about this child’.

“We all have a responsibility.”

House of horrors

During Desatge’s trial, where he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to life with parole eligibility after serving 22 years on September 19, the Crown said Desatge beat, ostracised, and eventually murdered Kaydence in “cold blood” because he disliked her biological father.

The detectives who worked the case, the only steadfast onlookers who sat in the public gallery during the trial, hoped he would serve at least 30 years.

The court was told Desatge beat the toddler with a bamboo stick which had a duct tape handle when she had accidents as an extreme form of toilet training.

The suspected murder weapon disappeared after Kaydence’s death - as did all her possessions.

His abuse reached an ultimate low, with the child left to sleep alone and unclothed in a toilet and forced to eat her waste as punishment.

On one occasion, Desatge threatened the child’s mother to do the same while holding her at knifepoint.

On what would have been Kaydence’s 10th birthday, September 23 2024, Ms Dawita was released from jail after serving an 18 month term, while in custody for four years, after she pleaded guilty to interfering with a body, aiding Desatge and lying about Kaydence’s whereabouts.

The domestic violence victim was acquitted of murder and torture before Toowoomba Supreme Court on September 17, 2024.

Justice Sean Cooper contemplated and documented his decision for about six weeks with the trial ending in early August 2024.

He said “in considering whether (Ms Dawita was) liable as a party… for the murder or manslaughter of Kaydence, I concluded that it had not been proved to the relevant standard that (she) intended or implicitly agreed with Mr Desatge that Kaydence should be mistreated”.

Justice Cooper found there may have been numerous reasons that led to her silence and lies, including fear of her abuser if she spoke out, fear of losing her children to the state, or shame that she didn’t do enough to protect Kaydence.

‘Never would have happened if she was white’

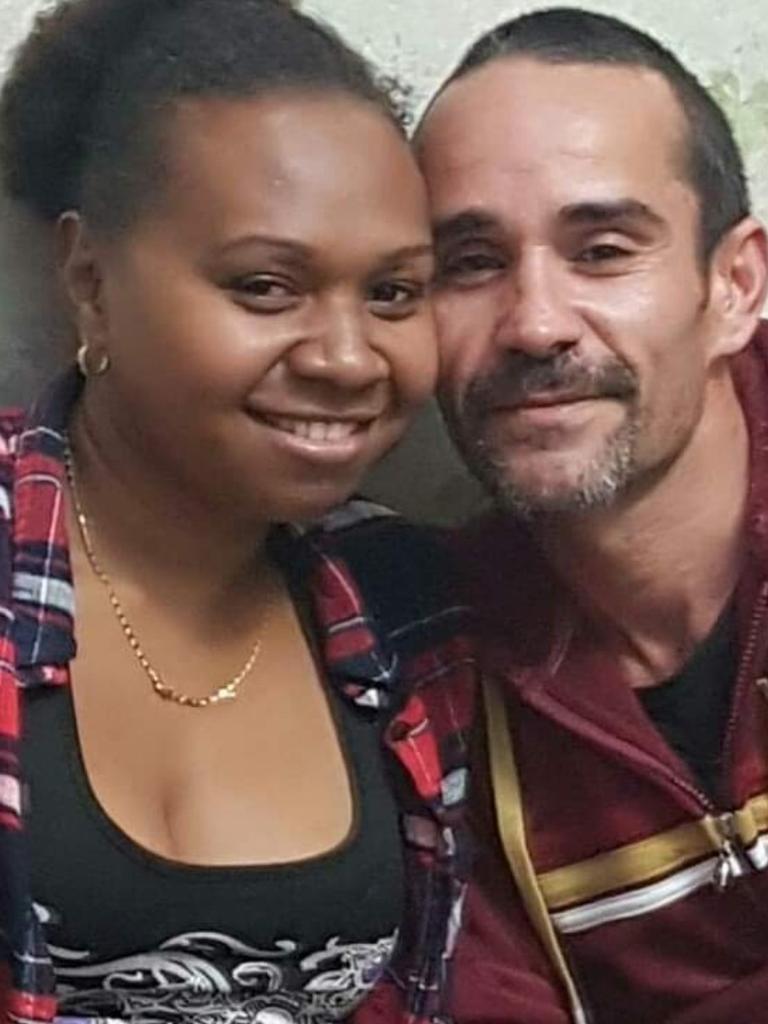

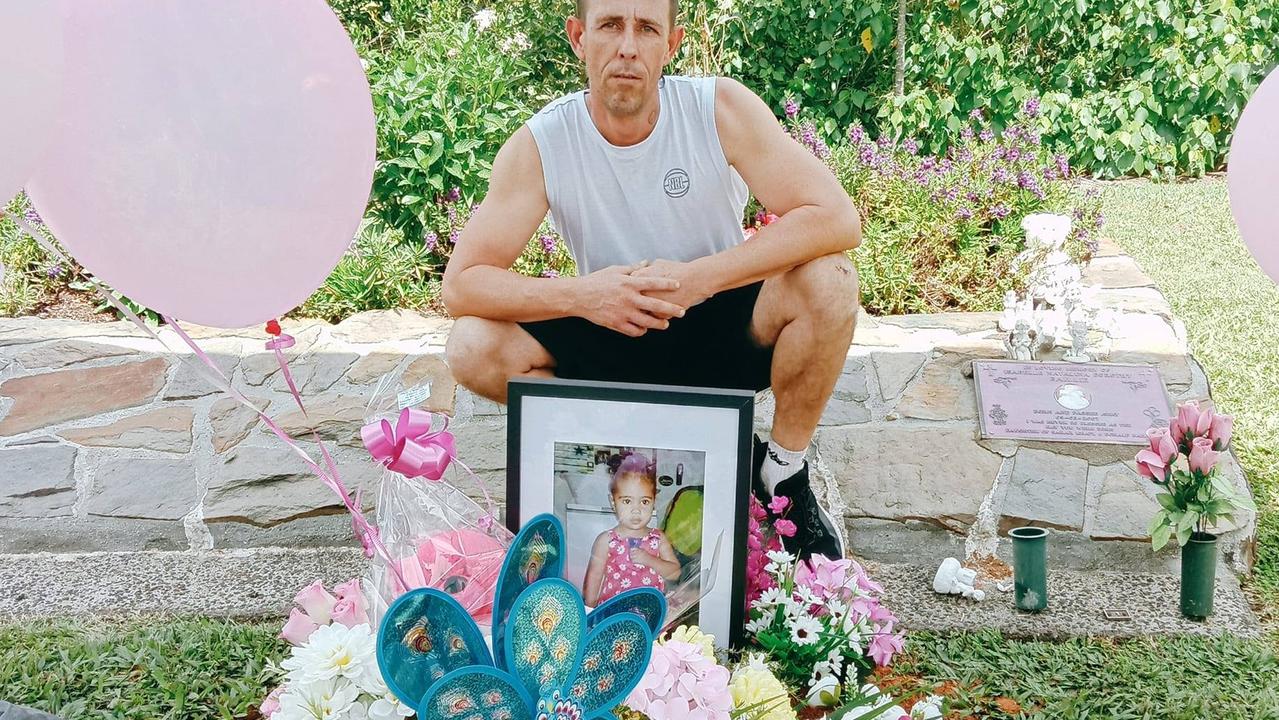

When Kaydence’s body was found, her father Mr Mills, told the Courier-Mail he first raised concerns for her welfare soon after she was placed in Dawita’s care.

The 40-year-old said he continued to make reports because he held grave concerns for his daughter.

The last complaint was made eight months before Kaydence’s remains were found.

Mr Mills believes his repeated requests made to the department about his daughter’s wellbeing were not taken seriously because of his criminal past, and the colour of her skin.

“There’s four documented (reports) since 2016, there’ll be three official documented ones where I have ... spoken to child safety in regards to her safety and wellbeing, because there were no photos of her, there was nothing of her for all these years, I was just getting fed lies and I was getting suspicious,” he said.

“They said ... ‘once a child is back with their biological parent out of child safety’s care, the department’s care, we are not bound by any legal law to investigate unless there is significant concerns of harm or danger to the child’s wellbeing’.”

Mr Mills believes race may have played a role in Kaydence falling through the cracks in the system.

“I think it was swept under the carpet ... because she’s of Indigenous descent,” Mr Mills said, adding that every day he struggled to come to terms with how his little girl came to be “discarded like rubbish”.

Mr Mills said more needed to be done so other innocent children did not suffer as his little girl had.

State’s response to concerns raised

A Department of Child Safety spokeswoman said legislation prevented the department from commenting on Kaydence’s case which was a “terrible tragedy”.

“We are committed to continual improvement and doing all we can to meet the needs of Queensland’s most vulnerable children, young people and their families so as to prevent future harm and deaths where possible.”

The spokeswoman said like all Queenslanders, it was appalled “at the level of cruelty inflicted on an innocent child and the level of deception from those meant to care for Kaydence”.

“We extend our deepest sympathies to Kaydence’s family members and friends and are gratified that the person responsible for Kaydence’s horrendous death has been brought to justice.

“All children have the right to grow up safe, connected and supported in their family, community and culture.”

What’s being done to protect others?

Child Safety Minister Charis Mullen echoed that of her department and said her “thoughts are with her family and community who love and grieve her”.

“My department and its child safety officers perform one of the most rewarding yet most difficult jobs in Queensland,” she said.

Mrs Mullen said the government made “sustained and meaningful reforms to help keep Queensland children safe,” which included a $2.3bn investment into child and family supports services this financial year.

“In the 2024-25 State Budget, our government committed funding for 1403 child safety officer positions,” she said.

“We created the Child Death Review Board, which since 1 July 2020 has provided systems advice to keep children known to the Child Protection system safe.

“We also raised the starting pay last year for child safety officers. As a result, we have seen a 130 per cent increase in applications in the first six months of this year compared to the previous year.

“We have created the role of the Child Safety Chief Practitioner, currently filled by Dr Meegan Crawford, who is implementing practice reforms to support our child safety officers to do their job in what are often opaque and volatile circumstances.”

She said the government was open to making necessary changes to “ensure our child protection system is strong and robust”.

“We will continue to build on this work through our $500m Putting Queensland Kids First strategy.”

What now?

The former Child Safety worker with firsthand knowledge of Kaydence’s case said the Queensland Child Protection Week motto this September was ‘Every child deserves a fair go’.

“That’s what Kaydence didn’t get, that’s what Mason Lee didn’t get, and that’s what unfortunately too many kids don’t get,” he said.

“When a child dies, the thing to remember is there can be system failings at the back end of that but along the way there are failings from society. In Kaydence’s case and in Mason Lee’s case, and even in the case of the two (Logan) girls who died in the car,” he said.

“There were failings by society, the family in general, and broader society not to actually raise the alarm sooner.

“More children would be safer if everyone had the bravery, and it is a brave thing to do, is call up and say ‘hey I was worried about this child’.”

“We all have a responsibility.”

‘Not a drop of rain’: Sunny, breezy break from storm season in store

The Darling Downs is set to enjoy near perfect weather as summer sets off, with stormy conditions in the rear view. See the week’s forecast.

Froyo frenzy: City’s first frozen yoghurt bar sells out in three days

Toowoomba has gone crazy for froyo, with the first ever frozen yoghurt bar selling out only 72 hours after opening its doors. Here’s when they’ll be back up and running.