Addiction in Australia: Why the ‘Just Say No’ message is not getting through

OUR largest drug and alcohol service provider for the young has a new take on addiction, saying the idea of telling kids “no” and hoping for the best is creating more harm than good.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

‘JUST say no.” It’s a sentiment heard commonly inside the walls of dimly lit high school classrooms or on our television screens, closely followed by a quickly spoken, “authorised by the Australian Government, Canberra”.

It’s a hard message for most young adults to digest when the discourse of sex, alcohol and drugs is opened in our schools and at the dinner table, especially when the message comes from preaching teachers and parents who have most likely engaged in one or all of these at some point in their lives.

It’s also proven to be totally ineffective.

According to Matt Noffs, who operates the Noffs Foundation — Australia’s largest drug and alcohol treatment service provider for young people under 25 — this idea of telling kids “no” and hoping for the best is creating more harm than good.

“We see in the US a system of abstinence-based sex-ed, telling kids to not have sex, which is totally ridiculous, and they have one of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the Western world,” he says.

“In France you see they have sex-ed based on pleasure and how you please your partner, and saying this is a part of life and will be a part of your life, and they have some of the lowest pregnancy rates.”

MORE STORIES

CELEBRITY BIKIE LINKED TO ROLEX REBIRTHING RACKET

HEARTBREAKING RITUAL OF MURDERED BIKIE’S MOTHER

In a similar fashion, Noffs believes the conversation about all things addiction needs a revamp for the modern world, which led him to write a book with psychologist and Noffs Foundation frontline worker Kieran Palmer.

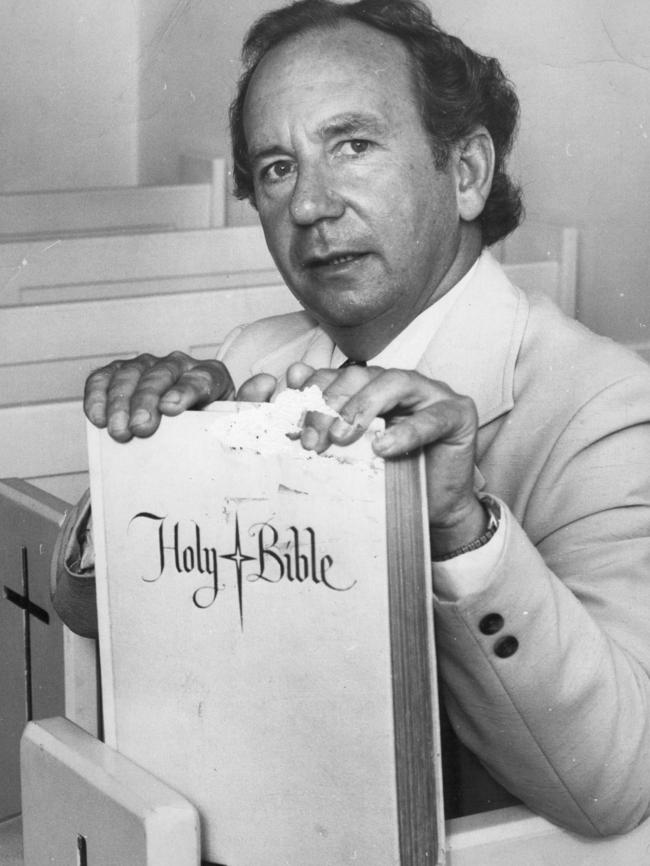

Noffs is the grandchild of Reverend Ted Noffs who, with his wife Margaret, established Sydney’s Wayside Chapel and co-founded Lifeline in 1963.

He comes from a family line that has been dedicated to changing the conversation around addiction, from being a stigmatising part of society to a natural part of the human mind.

“Addiction is quite simply a function of our brain, and in terms of you and I, when someone becomes addicted to heroin it’s like when you first fall in love,” he says.

“Your brain is primarily focusing on this object or subject and is preoccupied by the thought of this person, but in a few weeks, your brain will recalibrate, those chemicals become more subtle in your brain.”

His main goal is for people to understand that addiction affects all of us and is something we need to understand in order to make modern changes on how we fight the war on drugs.

“The only difference is, the person who has gone through the same mechanism with a drug like ice or heroin, they’re just not going to have that same recalibration,” he says.

Noffs was also the figurehead for Australia’s first pill-testing trial — at Canberra music festival Groovin the Moo in May — and says modern technology like this is vital to help kids be safe when moving in the world of drugs.

“Australia is one of the wealthiest and healthiest nations on the face of the planet, so that’s part of our mandate and our vision to make Australia the safest country when it comes to drugs,” he says.

“With addiction, when we understand it, when we separate it from that image of the person in the alley shooting up and as purely negative, it actually becomes really useful in itself and in inspiring young people.”

The way parents speak to their children about drugs also needs a reboot in his eyes.

“When we talk to kids about drugs we think of it as binary — that the opposite of saying no to drugs is saying yes to drugs — and that’s not the case,” he says.

“My kids are under 10 and we’ve already started talking about it.”

Noffs says he has never tried ecstasy himself, and while he doesn’t like the idea of his own kids trying it he believes it would be stupid of him to think they aren’t going to try drugs at some point in their lives.

“My way of talking to them about it is not scaring them but not saying to them it’s OK either,” he says.

“We should be saying to them, ‘listen, I don’t like the idea of using drugs because there are people out there who get hurt and there have even been young people who have died from this. However, if you decide you are going to experiment with it, I want to know and I want to be the first person you call if you get into trouble.’”

Another controversial point Noffs discusses in the book is society’s reliance on smartphones, and believes that the money used for ice ads could be better used for prevention against smartphones addiction.

“When the ice ads originally came out, most parents with ice-addicted kids felt that they couldn’t come forward and talk about it after that. They felt that they would be seen as monsters. So the government needs to put aside the politics and think if it’s actually helping people,” he says.

“Smart phone usage is ubiquitous and ice use is not, and we know smart phones addiction can cause mental health issues, so doesn’t it make perfect sense that the money should be spent for this instead?”

Originally published as Addiction in Australia: Why the ‘Just Say No’ message is not getting through