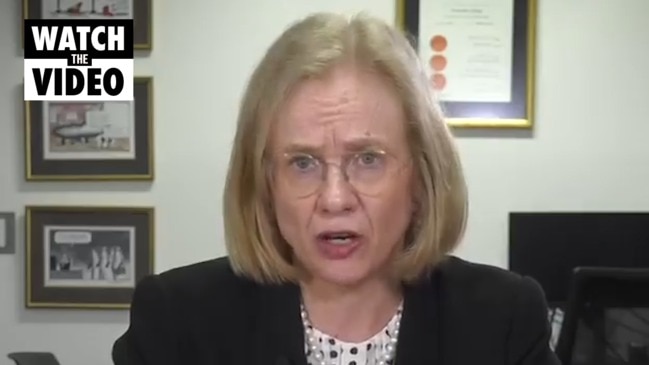

The real Jeannette Young: What you didn’t know about the State’s CHO

After a January meeting about a mystery virus spreading in China, Chief Health Officer Jeannette Young had a feeling of dread that she knew it would turn into a nightmare. Now she’s revealed the inside story of the fight to save Queensland.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Jeannette Young fights back tears as she emerges from a national hook-up of Australia’s chief health officers.

It’s mid-January and many Queenslanders are off enjoying their weekend, oblivious to a brewing overseas health crisis that’s starting to occupy some of the country’s best medical minds. Cases of a “mystery” virus are mounting in China.

Some patients are critically ill and on life support.

Others have died.

The contagion, a new type of coronavirus yet to be officially named, has already started spreading outside of China, with cases detected in Thailand and Japan.

Although the World Health Organisation is weeks away from declaring a pandemic, and Australia is still free of the infection, Young clicks out of the briefing with an inner sense of dread.

“I came out in tears. I thought: ‘I don’t want to do this.

This is going to be terrible for everyone. I just thought this is going to be a nightmare. And in hindsight I was right,” she recalls.

As tears welled in her eyes, Young grabbed her mobile phone and called her husband, Professor Graeme Nimmo, who was spending the weekend at Mooloolaba, on the Sunshine Coast.

Predicting what lay ahead, that she was about to be thrust into having to navigate Queensland through medically uncharted waters – the first coronavirus pandemic in history – she pleaded with him: “Graeme, you’ve got to come home. Now. I can’t do this without you.”

That night, as most Queenslanders enjoyed their Saturday evening, Young and Nimmo, a respected microbiologist on pre-retirement long service leave, discussed what needed to be done to keep people safe.

“He’s just been critical,” Young says.

“He’s my sounding board and so often, he’d go: ‘Oh, I’d just have a rethink about that one if I was you’. He’s always very, very wise. He’s exceptional. He can tell me things, genuinely, and say: ‘You’ve not got that right’.

He is the perfect person to be married to when you’ve got a pandemic, or you’re a chief health officer who doesn’t know anything about pathology and infectious diseases. It’s been a great team, purely by accident.”

Apart from his sage scientific advice, at the end of every day since then, as she’s arrived home from work stressed and exhausted, he’s had a “lovely meal” waiting on the table for her. “I’m so lucky,” she says, smiling.

The couple had an introduction to pandemic management in 2009, the year swine flu spread across the globe.

At that stage, they were both working – Nimmo as Queensland’s director of microbiology and Young was four years into her role as chief health officer.

They had two daughters still at home, the youngest then just eight.

“That was just a warm-up for this one,” Young says from her seventh-floor office at Queensland Health headquarters in inner-city Brisbane.

“I was lucky to do that one, in hindsight.

“I hated it at the time. I didn’t stop for six months. We were both flat out and we had young children. That was so hard. In the end, I got a nanny in because I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t manage. It was such hard work.”

Her weight plunged to 51kg. “There was nothing left of me after swine flu,” she confides. “I just can’t eat when I’m stressed, it’s terrible.”

Young vowed she would never lead Queensland through another pandemic, but here she is, 11 months into her second, the worst in a century.

She’s shed weight again, but tips the scales at a much healthier 55kg this time, thanks to Nimmo’s cooking and care.

Queensland’s pandemic virus numbers are also faring well – fewer than 1300 cases have been recorded, including six deaths.

That’s way short of modelling released by Young in March, based on what was happening overseas. At that stage, the data suggested 1.25 million Queenslanders could be infected in the first six months of the pandemic, with up to 250,000 needing hospital admission and potentially 12,500 deaths.

To put the projected deaths into perspective, that equates to every person in a town the size of Warwick, about 130km southwest of Brisbane, dying from the infection.

The enormity of what Queensland faced gave Young sleepless nights in the early days of the pandemic.

She would mull over her decisions, pondering: “Maybe I should do this or maybe I should do that’.”

Adding 30 minutes of daily exercise into her routine after getting out of bed at 5am has helped. She spends the time on her home treadmill, exercise bike or pilates machine.

“That’s really anchored me,” she says.

Young is Australia’s longest-serving chief health officer after 15 years in the job in Queensland.

In the midst of more than 60 million cases of the new virus across the globe, including 1.4 million deaths, she’s credited with being the architect of one of the most successful pandemic responses. But the praise sits uneasily on her shoulders.

“Seriously, I’m only one person,” she says with genuine modesty, sipping from a cup of tea, her favourite brew.

“Try not to make it about me. I’ve got this enormous team that is just brilliant. Each one of them is an expert in their own right. When brought together, they’re unbeatable. It’s been a magnificent joint effort.”

After years of handling cyclones and floods, Queensland, she says, knows how to manage disasters.

“We have really good systems in place. Our government works well with the senior bureaucracy and Queenslanders understand what needs to be done. The Queensland public has done the hard work during the pandemic. Their willingness to listen and abide by restrictions has made the most difference. If it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

But few working in the world of public health responses doubt Young has played a pivotal role in protecting Queenslanders from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. She’s acted decisively and politicians have listened.

Three days after that January 18 national hook-up of health chiefs, she fronted a news conference called to encourage adults planning overseas travel to get a measles jab, if they had not already been vaccinated.

Part-way through, the subject changed to the “novel coronavirus”. She was the first of Australia’s chief health officers to raise concerns publicly about the mysterious, highly contagious infection.

It was a deliberate strategy, she says, to begin preparing Queenslanders for what she feared lay ahead.

That week, she told her staff to go and enjoy the Australia Day long weekend because after that they would be “bunkering down”.

On Saturday, January 25, the first case of the new virus was recorded in Australia – a man in Melbourne.

The same day Young “stood up” Queensland’s State Health Emergency Co-ordination Centre, or SHECC – the medical equivalent of a war room.

It’s been going 24/7 since. Queensland confirmed its first SARS-CoV-2 infection on January 28. A day later, Young declared the virus a public health emergency – before any other Australian state and even before the WHO.

In pop culture terms, University of Queensland virologist Associate Professor Ian Mackay likens Young to Captain America, part of the fictional team of super heroes, the Avengers, in the 1960s comic book series, resurrected on film in the 21st century.

“The amount of expertise I saw in that SHECC is absolutely awe-inspiring,” he says.

“It’s like watching the Avengers assemble. Setting up SHECC really early on, with all the experts that were needed to start collaborating, was a great move and had Queensland in a really good position right out the gate.”

After spending three months working with Young inside the SHECC, Mackay describes her as a mix of humanity, intelligence and strength.

“Soldiers follow leaders into battle,” he says. “I would follow her anywhere. She’s smarter than me by about 1000-fold and is across everything.”

Goondiwindi Regional Council Mayor Lawrence Springborg, one of seven Queensland health ministers Young has served as chief health officer, says the state owes her “a great deal of gratitude”.

“If you compare what’s being done … around the rest of the world, where you’ve got very developed western-style medical systems and quite affluent societies, there has been manifest failure,” the former health minister in the LNP Newman Government says.

“We have not seen that here in Queensland. We’ve all got our opinions and opinions are fine. We can all have them because we need to debate and discuss things. But someone has to sit down and has to gather all the evidence and work out, among all that, what is the correct thing to do to keep people safe. I think she’s done an extraordinarily good job.

“From a health perspective, we’ve got virtually zero untraced community transmission in Queensland, which is a credit to her and our systems. That’s given people confidence.

“It also means that our health system, which has been put on a hyper situation of alert, has been able to cope.”

Young grew up the eldest of three sisters on Sydney’s North Shore with childhood dreams, not of becoming a doctor, but of a life on the stage as a professional ballerina. Ballet touched her intellectually, having to remember complex choreography, as well as physically and musically. “When I was four or five, it was just one of those things that most little girls seemed to do and I stuck with it,” she says. “I loved the ballet but it wasn’t going to be a career. I might have dreamt about it, but … it couldn’t be. I wasn’t good at it.”

She only decided on medicine in her final year at St Ives High School, a co-educational government school with the motto Optima Optime, Latin for “the best possible things in the best possible way”.

“No one had ever been a doctor in my immediate or extended family, or a nurse, or anything health related at all,” Young says.

“It wasn’t a burning ambition from when I was a young child that I wanted to be a doctor. But I’m glad I chose medicine.”

After completing what was then a five-year medical degree at the University of Sydney, she spent two years as an intern and resident doctor at Westmead Hospital, in Sydney’s west, before accepting an advanced traineeship there in emergency medicine.

“We had so many gunshot wounds,” she recalls. “There was a lot of trauma. It was a really busy, busy emergency department.

“You have to learn to make really quick decisions … based on the information in front of you. You couldn’t say: ‘Oh it would be really nice if we had this and this and this’. You just had to go with it.” They were mostly good days, those times in the ED for the then 20-something Young. Every shift brought something new, something unexpected.

“You can really save lives, you’re doing it on the spot and you use all your skills,” she says.

But sometimes, as in all hospital emergency departments, lives were lost, regardless of the skill – or will – of the medical teams involved.

One such night is still burned into Young’s memory although a quarter of a century has passed since. Eight people on her shift that day, mostly young patients, died in separate incidents – car accidents, asthma, “other terrible things”. “Every awful situation happened that night,” Young says.

“I’ll never forget it my entire life. It was just one of those horror, horror nights.”

She called in one of the hospital pastors to help her with the distressed families. And then, after the patients’ loved ones had left the ED, their lives changed forever, the pastor sat down with Young.

He was the only person who “realised how traumatised I was,” she says. “I was struggling.”

Her move into medical management came six-and-a-half years into her career as a doctor – not because she was burnt out working in the ED, but because she had her first baby, Rebecca, in 1991. “I loved working,” she says.

“There was no way on Earth I ever intended stopping work. But emergency medicine is 24/7 and not conducive to having a baby. It was truly, truly awful trying to find child care. I couldn’t believe it.”

Westmead Hospital threw her a career lifebuoy. Young was offered a job in medical administration as the hospital’s medico-legal officer and with it, on-site child care, which at the time had a three-year waiting list. After three months’ maternity leave, she took the office job.

“They wanted me to do a job that they couldn’t get anyone else to do,” she says. “There were just heaps and heaps of medical reports that needed dictating and managing and they needed someone to do it.

“It was a pretty awful job, but I got child care. I just thought it was so important to keep working. Once you stop working, in so many areas, you can’t go back. When I was on the medical board … all these women who hadn’t been in medicine for 30 years wanted to return. I just said: ‘You’re going to have to go back, do your medical degree again and start over. You’ve got to keep that connection’.”

As she reminisces about her life, the 57 year old is convinced women can successfully juggle family and career.

“I actually think you can have it all, with hard work,” she says. “You’ve got to work out what’s important in life and I don’t know if it’s that important to have a clean and tidy house. I like a clean and tidy house, but someone else can do that for you. I believe in outsourcing everything you possibly can, even if it means you don’t have much of your salary left because I just thought: ‘it’s so important to keep working’.”

After six months as Westmead’s medico-legal officer, Young was promoted to clinical superintendent of medical services, responsible for management of junior doctors. Juggling work and a toddler, she also completed a Master of Business Administration at Sydney’s Macquarie University, studying part-time.

“That was so much fun,” she says. “I found my medical degree sheer hard work because I was terrified that if I didn’t understand something … one day someone would die because I hadn’t understood that concept. I found it really hard, whereas the MBA, who cares?”

However, it was the MBA that transformed Young from an introvert “who couldn’t explain myself” or talk in front of a group, to someone able to speak confidently in front of anyone, about anything.

Two decades on, she draws on those skills constantly as one of Queensland’s most recognisable women.

Day after day she’s stood beside Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk, and former health minister Steven Miles as the face of the pandemic, simplifying complex medical messages to the masses. But it’s not stardom she covets. “I don’t want to be a celebrity – just a chief health officer giving the best advice she can,” Young says.

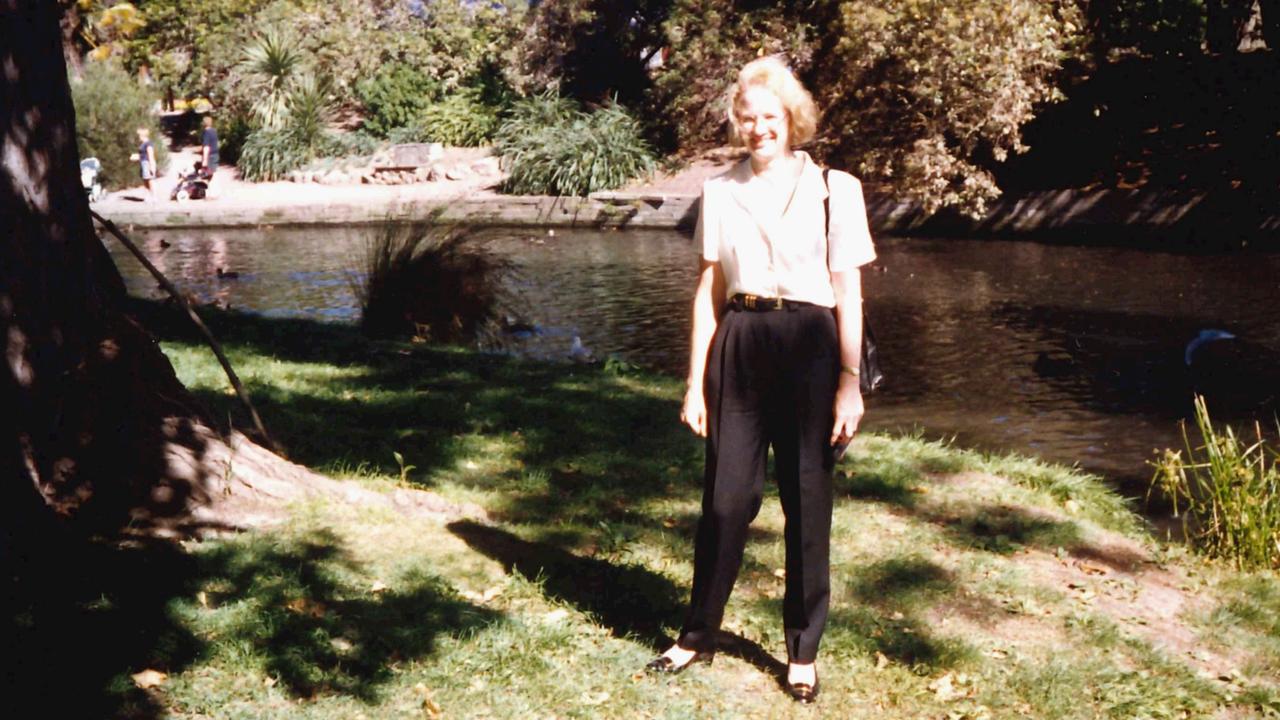

Had it not been for Queensland’s heat, she may never have moved north from NSW. She was a 31-year-old divorced single mum when she left Sydney to live in central Queensland, accepting a role as Rockhampton Hospital’s executive director medical services in December, 1994.

Rebecca was three. “I was looking for the next step – either to be a deputy at a big place, like Westmead, or to go and be a director at a smaller place,” she recalls.

Directors’ jobs were being advertised in two regional centres on the eastern seaboard – Rockhampton and Ballarat. “I chose Rocky based on the climate,” she says. “I love the heat, I absolutely love it.

“I think some people thought I was weird to go from Sydney up to Rockhampton. A few people told me: ‘Ooh, going up there, a single mum’.

It was the best decision I ever made. Rocky is a great place to bring up children.”

The job came with a house inside hospital grounds. In the evenings, she held meetings on her veranda. And during the night, if she was called on to sort out problems at the hospital, someone would come down to look after Rebecca.

“They were so good. They just looked out for us. I was very, very young. They took a real risk on me,” she says.

Halfway through her four years in Rockhampton, she was given a mobile phone. It was huge by today’s standards. But it freed her to take Rebecca exploring on weekends.

“Prior to that, I was pretty well stuck, because I was on call all the time,” Young says.

“It’s my own fault. I like to be in control. I was just on call, that’s what I did. But then, I got this mobile phone. I just said to Rebecca: ‘Let’s go and explore’.

After that, every weekend, we’d go somewhere. We’d go camping, down to Yeppoon or Blackdown Tablelands or up to Airlie Beach and a couple of the islands we got to know really well.

“We’d go sailing. There’s beautiful, beautiful places. I could not understand why it was so hard to recruit doctors. It was just impossible. I spent my entire time doing recruitment. That’s actually why I left because after four years … I thought: ‘I can’t keep doing this’.”

In January, 1999, Young started work at Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital as head of medical services.

She met Nimmo in her first fortnight in the job – working through a hospital IT system issue together. The new pathology computer system for the hospital, due to be implemented in six months, had to be rolled out immediately after water leakage into the server.

“We met together, over a computer every morning for a week,” Young says, with a laugh.

About 15 months later, they married.

The couple have a teenage daughter together, who is still at university. Their 20th wedding anniversary in March was meant to be celebrated on a six-week European holiday, with a five-day hike planned from Dijon to Beaune through vineyards and quaint medieval villages in France, and tickets to the Bolshoi Ballet in Russia.

“Ooh, it was going to be wonderful, it was going to be bliss,” Young says. But like so many other Queenslanders, their plans were quashed by the pandemic.

Young has had a torrid year. She’s had to make agonisingly tough decisions on domestic borders and hotel quarantine that have forced some families apart at times of tragedy and pushed businesses to the brink and beyond.

Death threats resulted in her receiving 24-hour police protection and she’s faced accusations of lacking compassion.

“I’ve had very, very few critical or nasty comments,” she says, in response to the attacks.

“People have genuinely been absolutely lovely. And the people who haven’t, often it’s because they genuinely have been badly impacted. It’s hard for people who have got sick relatives, it is really difficult. It’s terrible to not be able to see your family.”

Young knows. She has not physically seen her own daughter Rebecca, who is 33 weeks pregnant and living with her husband in Victoria, or her elderly parents and sisters in Sydney, since the borders closed in March.

“I’ve been desperate for that border to open,” she says. “It’s the longest I’ve gone not seeing them.”

The way Young explains it, closing Queensland’s borders in March was Public Health Principles 101.

“That was an awful decision to even think about doing,” she admits.

“Public health protocol is you try and minimise movement of infectious people. You don’t want people coming from a high area of infection to a low area of infection because it will just spread it and continue to spread it. I am a very, very conservative person. I’m always going to take the safest outcome.”

Queensland will never know how many lives Young has protected through the complex decisions she’s responsible for under the Public Health Act.

“That person you’ve stopped coming into Queensland to see their relatives, did that stop 50 cases?” she says.

“You don’t know because you’ve stopped them. The problem with prevention is you don’t know what you’ve prevented unless you go and look overseas at what’s happened. When I saw what was happening in New York, when they were digging those mass graves, our numbers were doubling in Queensland every four days and I was thinking: ‘We’re about to be overrun’.”

Instead, with Young at the helm, the coronavirus curve has been smashed in this state, but she warns SARS-CoV-2 is here to stay.

Queenslanders will need to remain vigilant. Some of those infected will face long-term consequences, potentially for the rest of their lives.

“Every disease for some people can cause catastrophic outcomes,” she says. “But this one causes more, I think, it really does, and we won’t know for a long time because this is a new disease that’s going to be in the world now going forward. There’s no way we can eliminate it.”

But after a gloomy year, Young is looking ahead to 2021 with excitement, not fear.

“I think next year will be fantastic, absolutely fantastic,” she says. “As long as people just keep that fundamental response, which is: ‘If you’re sick, stay home,’ then we’ll be fine.’’

PREGNANT MUM’S LIFE OR DEATH DECISION AND HER DRAMATIC WORLD-FIRST SURGERY

SURGEON KNEELS BESIDE TEEN WHO IS JUST DAYS FROM DEATH

As results from multiple COVID-19 vaccine trials show success, she’s already turning her mind to the next phase of Queensland’s response.

The logistics are enormous. To fully vaccinate every Queenslander, about 10 million doses will be needed, with the rollout planned to begin in March.

“They need to finish all the trials and the processes, all that has to happen,” she says. “It will be a perfectly safe vaccine. There are no short cuts. I hope to be one of the first people who lines up to get jabbed.”

But first she plans a visit to see her grandchild in Melbourne, borders permitting.