‘The incredible manoeuvre that saved 18-month-old baby from drowning’

A valuable skill young Zac Moana learnt in infant swimming lessons saved his life when he fell in the pool. Here are Laurie Lawrence’s tips for all parents.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was one minute, maybe two, that her toddler was out of sight.

Zac Moana, 18 months, had been happily playing with his older siblings and cousins at his grandparents’ house but his mother, Jane Moana – acting on an instinct to lay eyes upon her youngest son – went to investigate.

Horrifyingly, she found him unresponsive in the pool.

With the pool fence closed and Zac floating face up in the water, Moana jumped in, pulled him out, screamed for help and immediately began CPR.

Fortunately, all ended well for Zac. He regained consciousness and was discharged from hospital with no lasting damage, noreven any memory of his close call.

Moana, of Palm Beach on the Gold Coast, credits his infant swimming lessons with saving Zac’s life.

‘I was in tears’: The gripping inside story of fight to save QLD from COVID

Hannah’s untold story and the heart-wrenching goodbye

All of Moana’s five children – Blaze, 14, Caiden, 12, Lily, 10, Macy, 6 and Zac, now 4 – began swimming lessons at the Laurie Lawrence Swim School when they were four months old. One of the key skills childrenlearn in swimming lessons is rolling onto their backs to float.

Moana, 41, a primary school teacher at Elanora Primary School, was herself trained by Lawrence when she was a child.

She says the memories of her son’s terrifying close call on Valentine‘s Day, in February 2018, will be forever seared intoher mind.

“I’ve got no doubt his swimming lessons saved him,” Moana says.

“That instinct to roll on his back and get his face out of the water is from his swimming lessons.

“The outcome was the best it could possibly have been … I remember seeing some white foam coming out of his mouth. But hehad no fluid on his lungs or any brain issues.

“We say it was only one to two minutes that he was out of sight but if he was face down for those minutes it could have beena very different outcome. I still have visions of what could have been.’’

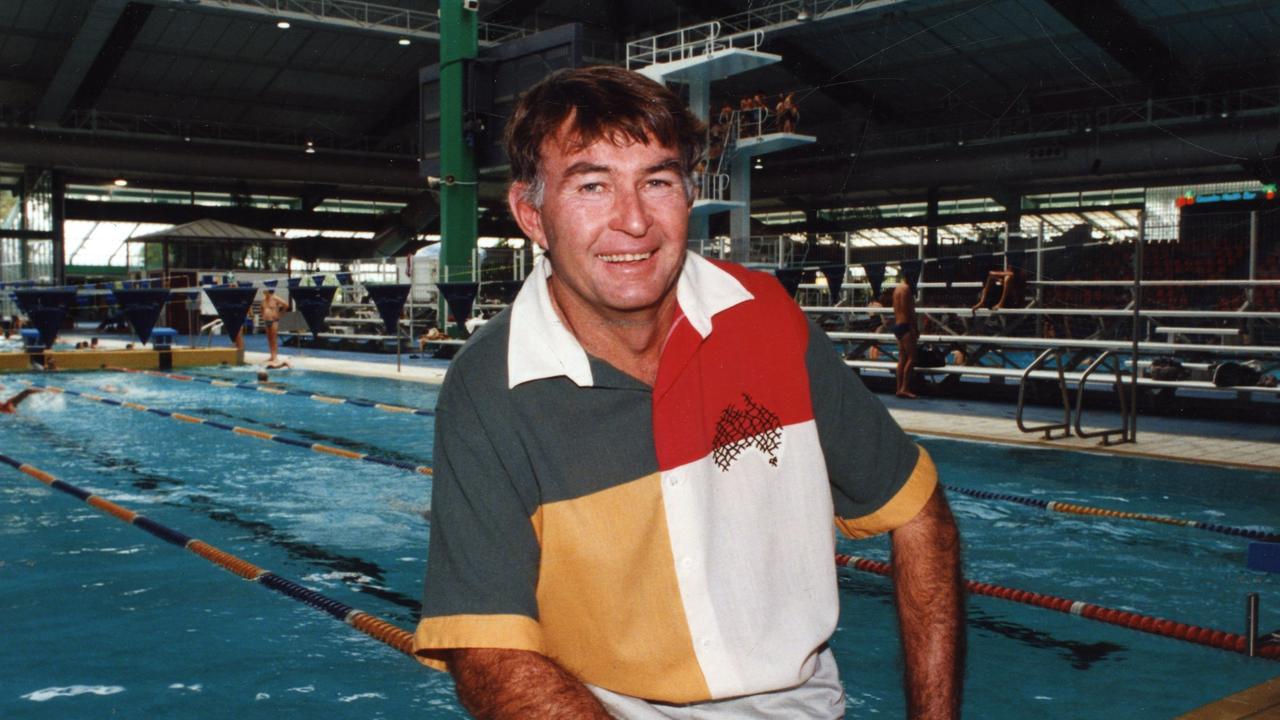

A child lost to drowning is a terrible thing. For Laurie Lawrence, it’s like a kick in the guts. A passionate and outspoken pioneer of water safety and infant swimming lessons, the former Olympic swimming coach has been the face of the Kids Alive Do the Five program for 20 years. Over that time, the number of children under the age of five who have drowned in Australia has fallen from 63 in 1999/2000, to 12 in 2019/20 (as stated in Royal Life Saving national drowning reports).

Though the numbers have vastly improved, Lawrence, 79, of Currumbin on the Gold Coast, says he won’t be satisfied until that figure is zero.

“When I hear about a child drowning, I feel for the parents,” he says. “I know accidents can happen and it just makes me determined to get those stats down to zero.

“That’s 12 families that have lost a little child to drowning last year. That’s a minibus full of kids.’’

Lawrence, who established his Laurie Lawrence Swim School in Queensland in 1966, officially began the national Kids Alive Do the Five water safety program in 2000.

His three daughters all work in the business. Emma, 36, is the managing director of Kids Alive, while Jane, 45, and Kate, 41, own the Laurie Lawrence Swim School at Burleigh on the Gold Coast. His grandchildren – Emma’s kids Evie, 11, and Harper, 8, and Kate’s 16-month-old twins Nate and Sophie – are also part of the action, featured in swimming demonstrations and monthly videos of their swimming progress.

Lawrence advocates beginning water awareness for babies from birth, pouring water on top of their forehead and letting it run over their face while in the bath. Formal swim lessons then start at four months.

He reveals he is “extremely fearful’’ with regards to the swimming safety of his youngest grandchildren, who have been having lessons since four months of age but are still too young to be able to swim independently.

“I know with the twins, I’m extremely fearful because they are 16 months of age and they can’t swim yet,’’ Lawrence says. “They can go under water and hold their breath but they are not yet independent in the water. It will take until the age of about two to be able to play and dive down to the bottom of the pool and get up.

“They may get it earlier. Jane, my eldest daughter, could do anything at 20 months. I’m hoping the twins will be as good as Jane was at 20 months – though still supervised, of course.

“But until then, it’s a fear. Kate has just bought a house on a lake. It’s fenced at the back but I’ve still reversed the gate so it doesn’t open out on to the water. I also put on a magnetic latch and hinges that automatically shut the gate if it’s opened.

“These two are beautiful, mobile kids ... and it only takes one little thing to happen, and they are so quick. If they fall over on the ground, they cry. If they fall in the water, there’s no sound.’’

Lawrence says he fell into the role of national swim safety advocate “by accident’’.

The seeds of the role stretch back to the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, South Korea, where Lawrence was coach of the 200m freestyle gold medal winner Duncan Armstrong.

When Armstrong won, Lawrence – exuberant and jumping for joy – animatedly declared to a television reporter, ‘Why do you think we come here for? Silver? Stuff the silver – we come for the gold!’. It caught the attention of government officials, who later asked him to promote pool fencing (introduced in Queensland in 1991).

“When I got back to Australia, Queensland led the world in preschool drownings per capita,’’ Lawrence says. “We had more drownings in Queensland per capita than any other place in the world. We had 27 drowning under the age of five in Queensland alone.

“The government wanted to bring in pool-fencing legislation and it wasn’t really palatable … no one wanted to fence their pools.

“They said, ‘Let’s get that silly bastard who jumped around at the Olympic Games to go around and tell people to fence their pools’.’’

Lawrence was paid by the Queensland government to travel around the state, educating the public about the five main causes of most drownings: unfenced pools, open gates, and lack of swimming skills, supervision and CPR skills.

Over the next few years, Lawrence watched as drowning statistics went down but then his government funding stopped. However, with no continued education campaign, Lawrence says the drowning numbers went back up.

The Kids Alive program was launched nationally in 2000 with federal government funding and, in 2009, a water safety DVD (replaced in 2019 with a Living With Water book) was distributed free as part of a new parents’ Bounty Bag. More than two million DVDs were given out, with 261,000 books distributed in the 2019-20 financial year.

Lawrence also created his World Wide Swim School, an online platform for parents, coaches, teachers and swim schools that features videos of his grandchildren’s swimming development. It now has 10,000 members in 100 countries.

Lawrence didn’t learn to swim until he was 10 years old. Afflicted by a lung disease called bronchiectasis throughout his childhood, he had part of his lung surgically removed at age 10, and his doctors advised he take up swimming to strengthen his lung function.

His father, Alan “Stumpy” Lawrence – formerly a shearer’s cook and publican at Winton and Townsville – took up management of the Tobruk Memorial Baths at Townsville as a result. The pool, on Townsville’s foreshore, was the training location for the 1956 and 1960 Australian Olympic teams in the golden era of Australian swimming.

Living in rooms above the entrance of the pool, Lawrence grew up getting autographs from the likes of swimming greats Dawn Fraser, Murray Rose, John Konrads, Lorraine Crapp and David Thiele.

Lawrence later moved to Brisbane when his parents separated, attending St Laurence’s College and then Kelvin Grove Teachers’ College.

A keen rugby union player, Lawrence was selected for the Australian team for the 1964 tour of New Zealand.

He worked as a physical education teacher, then moved back to Townsville and began teaching kids to swim at the pool. He married his wife Jocelyn, now 66, in 1974.

Lawrence was part of Australia’s Olympic swim coaching team for the 1984 (Los Angeles), 1988 (Seoul) and 1992 (Barcelona) Olympic Games, with his best-known proteges including Steve Holland, Tracey Wickham, Jon Sieben and Duncan Armstrong. Then, with a brief to “unite, inspire, motivate and relax’’, he was the official team motivator for the Games in 1996 (Atlanta), 2000 (Sydney), 2004 (Athens) and 2008 (Beijing). He also coached Australian swimmers at the 1982 and 1986 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane and Edinburgh.

Lawrence was inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame in 1991 and awarded the Australian Sports Medal in 2000.

He has also been honoured in the International Swimming Hall of Fame for coaching and infant aquatics.

Everyone needs life mottos, and Lawrence’s are these: The standard you walk past is the standard you accept (“if you are teaching or coaching or doing stuff, don’t be satisfied with crap’’); and the people you meet on the way up, you see on the way down, too (“so treat ’em right, my father used to say’’). He takes pride in the difference his swim schools and education programs have made to child-drowning statistics.

But it is also personal. He is touched by the stories of families he has known over the years. One of his daughter Emma’s friends, who was with her four-year-old brother when he drowned in a dam, now brings her own children to his swim school.

“The experience of losing her brother is still burnt indelibly into her soul,’’ Lawrence says.

“She didn’t think she’d be able to bring her kids to the pool but now she’s so proud of herself, because her two kids are learning to swim and they love the water.”

Another woman has sent Lawrence a Christmas card every year for 40 years, grateful for him teaching her daughter to swim after losing her other daughter to drowning. Her daughter is now a psychologist. Hearing those things means the world.

Laurie Lawrence’s latest book, Stuff the Silver, We’re ... Going for Gold, available from laurielawrence.com.au

Kids Alive Do the Five:

- Fence the pool

- Shut the gate

- Teach your kids to swim, it’s great!

- Supervise! Watch your mate

- And learn how to resuscitate