‘The enormity of it all sank in’: bereaved FNQ sperm donor discovers ‘bonus family’ he never knew existed

After the sudden death of his only son Dr Darren Russell moved to Queensland to make a fresh start. Then he got an email that changed his life forever.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fatherhood came as a shock to Darren Russell. More than once.

The 23-year-old medical student and pool attendant was living in a Melbourne share house when he and girlfriend Janine, a 24-year-old marketing student, found themselves facing an unplanned pregnancy.

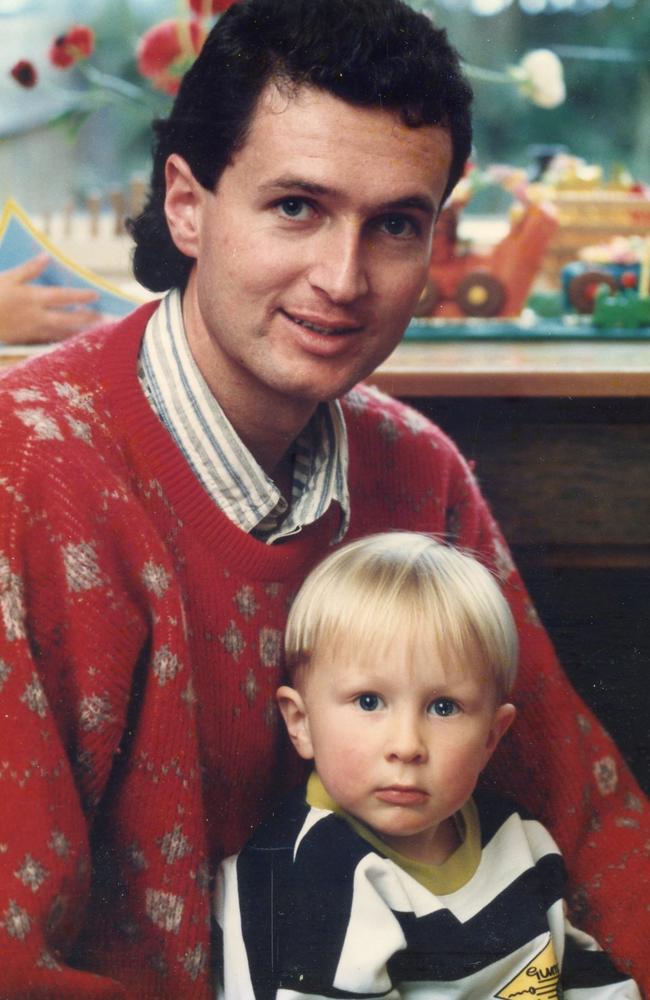

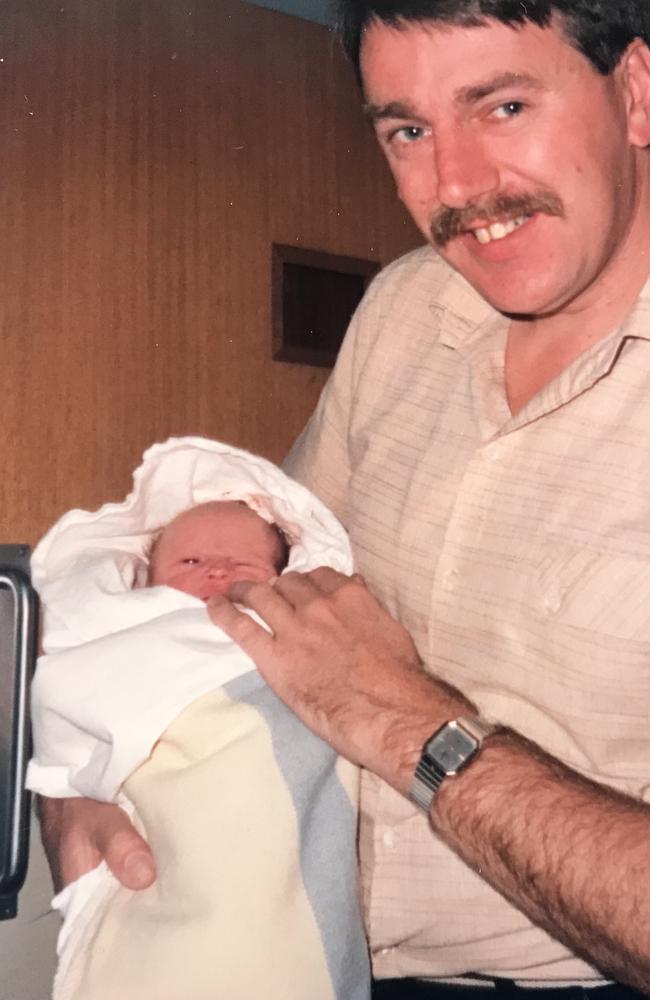

The couple moved in together and Bryn Akira Russell was born on September 19, 1986, the beloved first grandson and first nephew for both sides of the new family.

“(Having Bryn) was pretty amazing … but it was a lot of work.

No one prepares you for that.

We had a home birth and then everyone leaves. You’re left with this baby you’re supposed to know what to do with – how to feed it and how to change it and how to bathe it and how to look after it,’’ Russell laughs.

“But yeah, it was wonderful. I enjoyed all that stuff and the older he got, the more interaction there was with him as a little person, the more I engaged with him and got to love him as parents do with their children.’’

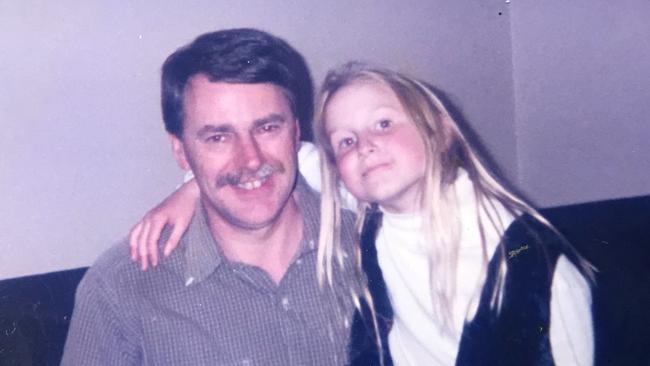

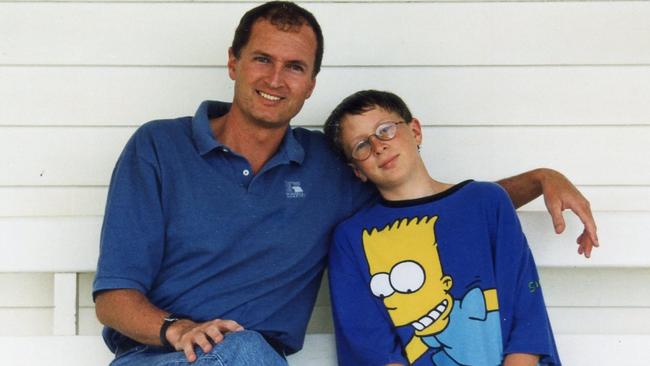

When Russell and Janine’s relationship broke down after five years, they shared custody, living close to each other and schools.

Bryn had keys to both homes, which Russell soon shared with wife Alemka, and loved weekly overnight stays with his late paternal grandma, Ursula.

Father and son shared a passion for judo, reading, swimming, the beach and adventures.

Then one day, seemingly happy, with a good circle of friends and doing well in Year 11, their “delightful, good-natured, engaging, loving” boy didn’t come home.

Bryn took his own life in March 2003, aged 16½.

“Grief of that magnitude, it’s a physical thing. It’s not a sadness. You can almost point to where it is in your chest. The colour drains out of everything. You stop singing. Life is monochrome and you’re going through the paces – get up, do what you need to do, but there’s the lack of joy in anything,’’ says a tearful Russell.

Bryn was cremated, Janine spreading half his ashes in the Gippsland national park they loved to explore together, while Russell keeps half close at home.

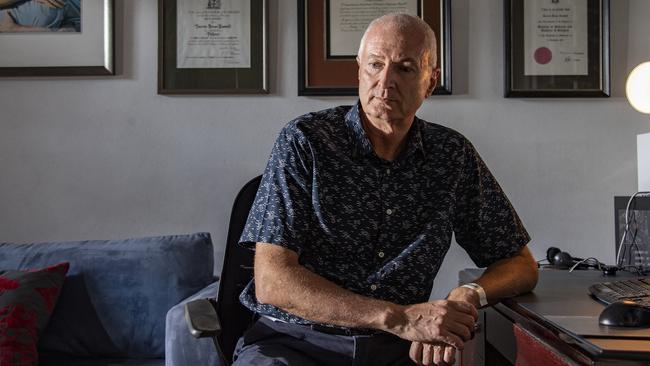

Two years later, Russell and Alemka, a psychologist, took a chance on a fresh start in far north Queensland, Russell accepting the role as director of Cairns Sexual Health, now also holding positions with James Cook and Melbourne universities.

“It was much easier not having to face the reminders every single day, the memories in Melbourne which just kept coming up. Certainly, a big part of our lives was gone and I was no longer a father. That does change things. I missed being a father, that’s for sure.’’

Then fatherhood shocked Russell again.

On June 16 last year, he was notified via an email from ancestry.com of a 50 per cent DNA match with a Victorian man.

Domino discoveries meant that within 12 months to the day, the 59-year-old doctor and associate professor learnt he is the biological father of nine donor-conceived adults, born to seven couples across greater Melbourne.

“Alemka and I were very happy without children; it might have been nice but we had decided not to (have them) and were comfortable with that.

So, to suddenly have nine children and 12 grandchildren thrust upon me totally out of the blue has been, the word I use is discombobulating,’’ says Russell, who is now getting to know most of them and their families.

“Everything you think you know in life and where you’re headed is suddenly up for grabs. It’s new, it’s exciting, it’s a marvellous adventure.’’

Still, he’s painfully aware not all these people even knew he existed, let alone were looking for him.

Several are still reeling from the traumatic betrayal of the only parents they’d ever known, left grappling with the question, who am I?

It had been three years since Russell, on a whim, took advantage of an ancestry.com sale and paid about $130 to confirm his Irish and Scottish roots – with an unexpected fraction of Viking blood.

Every now and then he’d be notified of a match with a distant cousin, interesting but of little consequence.

Then while Russell and Alemka were in Melbourne for a few weeks last year, settling his mum – robbed of independence by dementia, and since deceased – into an aged care facility and preparing her home for rental, the fateful email was opened.

“I Facebook stalked him. He was too young to be my father but he could be my son. He actually looks like me. I was stunned, absolutely stunned. My first thought was, who could I have had sex with in my 20s that had a child I didn’t know about? That’d be unlikely. I was friends with a lot of these women, they’d have told me or I’d have heard something. The second thought was it was a bizarre computer error and a million people around the planet got the same email,’’ he says.

After speaking with Alemka, Russell sent the man a message.

The quick reply explained he’d been conceived with donor sperm and had been looking for his biological father for several years, and had been told the fertility clinic’s records had been lost.

“I really hadn’t thought of the sperm donation at all, that did not enter my head at all. Then the enormity of it all sank in,’’ he says, describing their first online conversation as a delicate dance of consideration for each other’s feelings.

“There’s no etiquette guide here, no guide book on how to interact.

Suddenly there was someone who was my DNA, my biology, my biological son, who had been on the planet 29 years without me knowing.

Then he says, by the way, let’s just rip the Band-Aid off, I’ve got a sister with the same biological father. So, now I’ve got two kids.

“It was very emotional for me, very emotional, and I was quite stunned because I’d not ever contemplated this. I never knew if they used my sperm and, if it had been used, if there had been a pregnancy and someone born as a result. I had none of that information.’’

Russell was raised in Melbourne by late clerk Ursula and car mechanic Brian, 80, with younger sister Jayne, a maths professor, as well as siblings Damian, Natalie, Lisa and Janine from Brian’s second marriage to Carmel.

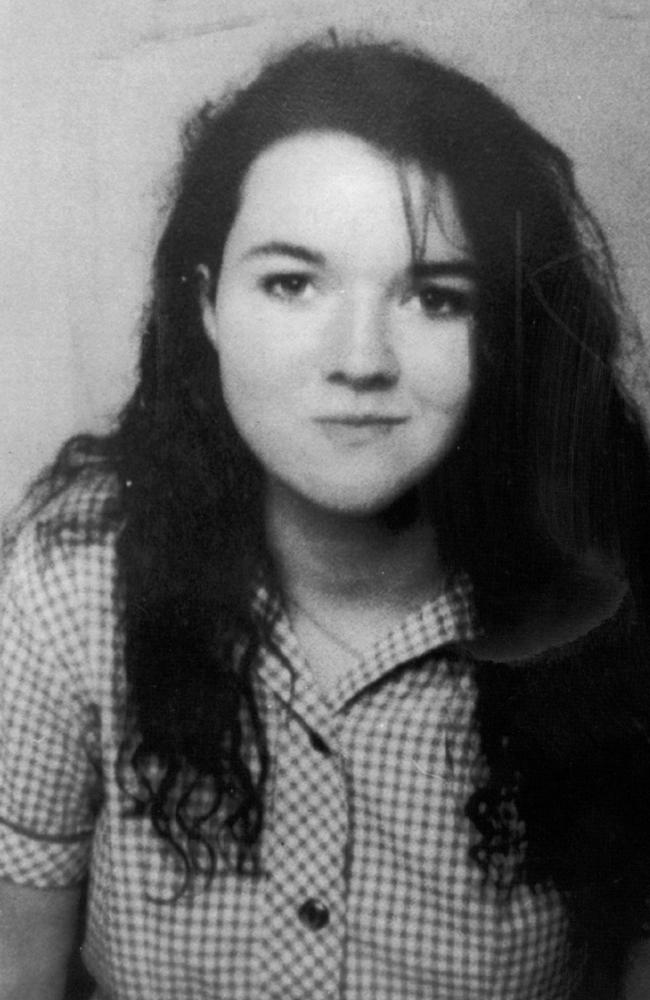

Natalie, 17, was murdered walking home from school in 1993, the last known victim of serial killer Paul Denyer, who is eligible for parole next year.

Fight to keep Frankston serial killer behind bars

Russell enrolled in the six-year University of Melbourne medical degree because he had the marks and liked the idea of helping people.

Already a regular blood donor, he saw becoming a sperm donor a natural extension of his “civic duty” after seeing a poster thumb-tacked to a campus noticeboard – a decision supported by his parents.

“I can’t recall ever thinking through the consequences that what I was doing was helping to create another human. I didn’t think about it much more than I did when giving blood,’’ says Russell.

“You don’t get the name of the person who you donated blood to.”

The process was somewhat more professional than that of a pioneering Queensland clinic run by Dr John Hennessey, where in the late 1970s and ’80s University of Queensland medical students filled out a basic form, underwent an exam and left their sperm donations in a “hole in the wall” of a carpark, taking an envelope containing $10 cash in exchange.

The Courier-Mail revealed Dr Hennessey apparently kept records “in his head” and a veterinarian verified the quality of samples.

’Baby factory’ stories spark search for late donor’s children

Nurse revealed fears of future for students involved in early fertility operation

The Qld baby factory that has our top doctors fearing a knock at the door

On March 17, 1982, Russell, then 19, underwent a physical examination at Prince Henry Research Medical Centre, St Kilda, and filled out a four-page form detailing basic family and health information, physical characteristics, results of blood and semen tests, and agreeing “never to seek the identity of any child or children born following upon the artificial insemination of any recipient of my semen, nor seek to make any claim in respect of any such child or children in any circumstances whatsoever”.

He is unaware – then or since – of any peers who also donated.

The centre’s reproductive medicine arm was established in 1976 by Dr Doug Lording and future Victorian premier Dr David de Kretser, initially recruiting sperm donors among medical students and those of the Victoria College of the Arts. Prince Henry’s, Queen Victoria Memorial and Moorabbin hospitals amalgamated to become the Monash Medical Centre in 1987.

Australia’s first sperm bank was established in Adelaide in 1972 and the first IVF baby, Candice Reed, was born at Melbourne’s Royal Women’s Hospital in 1980.

Once a month for the next 12-18 months, Russell abstained from sex for two to three days before riding his bike or the tram to the red-bricked building, where he collected a key and yellow-topped specimen jar from the lab attendant – “it was always an attractive young woman, always” – and climbed the stairs to the men’s bathroom, walking in past the urinals to unlock the door to a small, dimly lit room.

“There was a kind of bed there and pornographic magazines – I don’t know if they were supplied or if men brought their own inspiration and left them behind – but the worst thing was the faux leopard skin bedcover.

Anytime I see faux leopard or faux tiger, I’m transported back 40 years,” he says.

“I’d produce the specimen into the container – which takes a bit of dexterity – then go back downstairs to the attractive young female behind the counter, hand it over and she would give me a cheque for $10.”

Russell wasn’t, and finds it hard to believe any donors could have been, financially motivated. “It wasn’t a sizeable amount of money.’’

He was working about 35 hours a week as a lifeguard and pool attendant.

At the time, a man’s average weekly wage was $324.40, petrol was 30c/l, a pot of beer around 84c and a loaf of bread 54c.

Informed by the clinic towards the end of 1983 his donations were no longer required as there was plenty in storage, he was never contacted again – apart from a request to be tested for HIV in 1985, which he complied with.

Disillusioned with medicine, Russell took a year off to work, save money and backpack through Southeast Asia.

He was held at gunpoint by Thai soldiers before becoming comrades over karaoke, cared for by “Bangladesh’s No.1 sexy film star, as she described herself” after contracting amoebic dysentery in Nepal, and fled India amid the violent uprising after the assassination of Indian prime minister Indira Gandi.

Arriving home seriously ill, he spent several days in hospital with Hepatitis A, a virus affecting the liver.

Medicine “suddenly made more sense”, having helped fellow travellers with their rashes, bumps and cuts, and experienced first-hand the rudimentary facilities overseas.

Resuming his degree, it wasn’t long before Russell was juggling a new baby with final year exams and work.

Specialising in general practice and sexual health as the HIV/AIDS pandemic gripped the world, he landed a job with Dr David Bradford, founding fellow and one-time president of the Australasian College of Sexual Health Physicians, caring for marginalised patients – gay men, sex workers, drug users.

“I had found my niche. Intellectually it was very stimulating and cutting edge and there were lots of developments happening, so it was very exciting, but also the patients were so grateful and I was able to help them and really became part of their community.

“It was a real privilege to be able to work with people and see their lives.’’

Immediately after learning of his two offspring’s existence, uncertain what to do or where to go for help, Russell started Googling and came across the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority (VARTA).

Formed to regulate fertility clinics, the government-funded organisation also oversees information about people involved in donor treatment procedures.

The state’s right-to-know legislation commenced in March 2017 giving all donor-conceived people, no matter when they were born, the right to know their heritage.

Previously, people conceived as a result of gametes donated prior to July 1988 could not access information about their donors, and from June 2015, only with the donor’s consent.

Russell registered to allow contact. He never considered remaining anonymous.

“I started this process 40 years ago and as my father said (when I told him), we have a responsibility. That is part of the role I took on, though I didn’t realise it at the time.’’

Within a week, he’d heard from Cate Smith, 35, a lawyer who had been looking for him for seven years.

Smith and her brother, 38, who wishes to remain anonymous, lost their parents Allison and Jeff separately to cancer as teenagers and learnt of their origins from their maternal aunt, who revealed their parents always intended to tell them as adults.

The trio exchanged emails.

“Then we had a Zoom (call) and it was a wonderful thing just to see them. I saw Cate’s kids and her partner popped in at one stage. Alemka and I were able to have a lovely long chat with them both,’’ smiles Russell.

“It’s partly like getting to know a stranger but it is someone you’re related to on a DNA level, so there’s almost the feeling of obligation that you should make this work. It’s like a first date. You want to show you’re interested but you don’t want to come across all stalkerish and over-keen – they’ll run a mile; and you don’t want to be too stand-offish. And they’re trying to do the same thing.’’

For her part, Cate says she immediately felt comfortable with Russell and believes her parents would also have liked him and supported their relationship.

“One of the first things (my brother) and I did when we spoke with Darren was to thank him, both for the life we had but also on behalf of our parents, because if they were alive, they would have wanted to. Being parents gave them a lot of happiness and purpose. If he hadn’t done what he’d done, then my parents might not have had the life they wanted,’’ she says tearily.

A similarly emotional Russell credits this simple gesture with allaying his fears of having harmed rather than helped couples as he’d intended.

So, he travels to share a beer at the pub with his ancestry.com emailer One – for ease and to protect anonymity, he refers to them in numerical order of discovery – while One’s sister, Two, does not want contact.

An afternoon picnic in a Melbourne park with Cate and brother Four’s families follows several more video calls and emails.

“Then Cate just happened to drop into conversation that she has eight brothers and sisters through this process. I was like, what, nine?! Nine of you?! Yeah, didn’t they tell you? I’ve got information with all my siblings’ details,” he says. “That was the next thing, to make an application to get in touch with all of them. That was a big decision. This could cause good or it could cause harm, or it would likely cause both.’’

As Russell outlined in his submission to the recent Queensland Parliamentary Inquiry into Matters Relating to Donor Conception Information – arguing for a central registry similar to Victoria’s – he was motivated by a natural desire to have contact with offspring sharing his DNA and give them the chance to know him, to share his family medical history, and a fear others may know of his existence but be thwarted by agencies saying records had been lost or destroyed – as One and Cate had been told.

“Perhaps most importantly, I am struck by the proposition that the donor-conceived person is the only one who did not sign an agreement regarding confidentiality, and yet they are undoubtedly the one most affected. It seems profoundly unfair that actions taken by their parents, the clinic involved and me … would be unable to be questioned by the person born as a result,’’ Russell submitted.

VARTA – which also provided information to the Queensland inquiry and is due to report imminently – sent registered letters, in what Russell considers the “least worst” method, to five people connected to him, saying it had information about their births and to talk to their parents or call a provided number.

Two recipients had grown up knowing they were donor-conceived and were happy to be contacted. Three did not know.

The bottom fell out of their worlds.

For Riley, person Six, a 38-year-old health worker and single parent of one from Geelong, the letter arrived on yet another day working from home in the middle of yet another lockdown.

Neither of their younger brothers got one.

They called the number listed and spoke to the counsellor.

The man Riley called Dad until his death a few years earlier did not share their genes but was their brothers’ father in every sense of the word.

“If I picture what it felt like, it was like watching a piece of material holding everything together being unpicked bit by bit down the seam,” says Riley (not their real name), who describes feeling suicidal in the first chaotic days.

“Everything has shifted. It’s not like a sliding doors moment because I’ll never have the opportunity to go back to my reality where I knew who I was and what my place in the world was. Now none of that is true. I’m relearning who I am and re-identifying myself,” they say, admitting to at times second-guessing what they always considered a normal, happy upbringing.

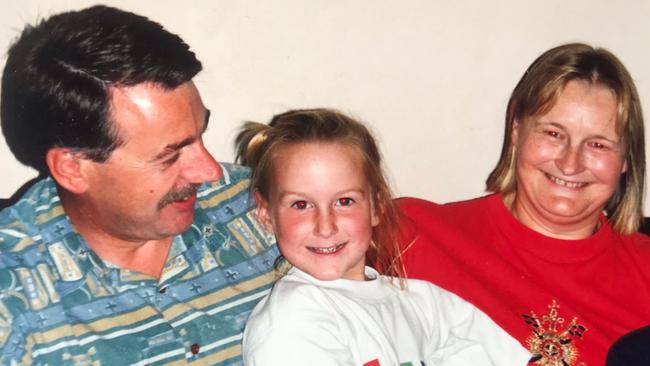

For Sunbury’s Jessica “Jazz” Banchero – person Seven – there was an immediate, visceral and physical response. Confused by the letter, the only child of a costumer and a fitter and turner immediately phoned her mother.

Hours later, listening as her mother shared her secret, a grief-stricken, disbelieving Banchero collapsed in a mess of tears and vomit.

“I’ve never been more furious in my life. The deception is absolutely horrendous. It’s like losing my dad all over again. I made the decision to turn his life support off when he was in a coma after a heart attack, I organised the funeral, I wrote the epitaph on his gravestone, everything, because my mum couldn’t do it,’’ says Jazz, a teacher and mum of two.

“I’m not even the nationality I thought I was. For a wog family, your heritage is extremely important and I was raised Polish, German and Serbian. I’m not Polish. I’m Irish. It’s a huge cultural shift. It’s devastating.”

She audibly cringes describing the thought of “being paid to be made” as “quite seedy” and “back alley”, though she acknowledges the motivation.

Thomas, person Eight, found out two days before Mother’s Day. The Geelong health worker and father of three, 38, likens the emotional rollercoaster to the indescribable Japanese flavour combination, umami.

“It’s a combination of all these emotions that aren’t necessarily congruent with each other. You’ve got angst yet you’ve got a bit of peace, there’s anger, there’s some curiosity and all thrown into a basket so you can’t identify which emotion is which. That’s quite challenging,’’ Thomas says.

An only child, his parents divorced in his early teens and his relationship with the man he knew as Dad was “not great”. The man he now refers to as Rob, rendered sterile by childhood mumps, remarried and died of cancer two years ago.

“I felt like I already knew. I used to ask if I was adopted because I felt the same way as cousins, who knew they were adopted, spoke of feeling. But I was always told I wasn’t,’’ says Thomas (not his real name), his sense of betrayal exacerbated by the number of family and friends who also kept the secret.

“Mum said, they told us not to say anything back in the day, blah blah blah. Be that as it may, I’m a fairly open person and there’s been a few points in my life where it was probably pertinent – getting genetically tested for the cancer that killed Rob wasn’t required. Things along those lines that could have saved me some angst.’’

Today, the nine are each at different stages of understanding and acceptance, each using a mix of professional counselling and family support, as well as that of their “bonus family” – as they refer to each other.

Neither Riley, Jazz nor Thomas is confident of rebuilding good relationships with their mothers, no matter how much they might want to.

Sense of self is a work in progress for most but Cate describes coming out of the “self-discovery process with an almost binding clarity of who I am and my place in the world … confident and centred’’.

Cate, Riley, Jazz and Thomas all struggle to put their grief and “what ifs” for Bryn, the brother they will never meet, into words.

Still, they’re enjoying getting to know each other and “New Dad” or “Bio Dad”, as Darren is generally referenced as, and marvelling over uncanny similarities, common interests and how the siblings have never crossed paths before – despite so many near-misses it’s laughable.

“Each new member is as lovely and respectful as the next – we often joke that decency must be in the genes. (Darren) has fostered beautiful connections between us all,’’ laughs Cate.

Footy rivalries have been the biggest source of contention – most are Geelong fans, with two lone Essendon and Hawks supporters.

“The initial difficult thing was that Darren is a Collingwood supporter and I always thought I was genetically better than that,” quips Thomas, the lone extrovert, who has already affectionately dubbed Cate “Blondie”.

There was even something of a family reunion – Russell-palooza, as one wag dubbed it – over a pub lunch in Melbourne on a recent Sunday, when Russell and Alemka stayed in the city for two weeks to either meet for the first time or catch up with all of them. Thomas and his family head to Cairns next month.

“If you’d asked me last year, I wouldn’t have called them family and I wouldn’t have called them son and daughter. That would have been too close, too intimate and it wouldn’t have felt right. With the passage of time and getting to know them, I do think of them as family,” Russell says. “I send them all birthday cards now. I’ve had to get a new app because there’s so many birthdays – nine kids, their partners, 12 grandkids so far and probably more next year.’’

Support and information for donor-conceived people, parents and donors: donorconceivedaustralia.com.au