The Qld baby factory that has our top doctors fearing a knock at the door

As young men, some of Queensland’s top doctors were lured into what was then a groundbreaking fertility treatment for just $10 and the promise of anonymity. Forty years later, advances in DNA science and technology mean they are now living in fear.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Top doctors who were lured as bright University of Queensland medical students four decades ago to “anonymously” donate sperm are now living in fear of a knock on the door from the children they helped conceive.

A Saturday Courier-Mail investigation can reveal that Queensland fertility pioneers who were conducting then-revolutionary treatments to help childless couples gave lectures at the university targeting highly intelligent medical students to become sperm donors in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

At least 30 students from the UQ medical school were donating sperm to a groundbreaking clinic at Wickham Tce where respected fertility medicine doctor John Hennessey had rooms with three other doctors.

One highly respected Brisbane specialist – whom the Saturday Courier-Mail will refer to as Doctor X – has revealed that he and his university mates who were donors fear they could be approached by donor-conceived people at any time.

“We believed it was anonymous and couldn’t have guessed that in our lifetimes there would be the technology available for anyone to track us down,” said the doctor, who works in a city clinic.

The then-cutting edge donor conception procedures at the Wickham Tce clinic were pre-IVF and involved basic insemination with fresh rather than frozen sperm.

Dr Hennessey went on to help conceive and deliver the state’s first IVF twins in 1984.

While the young men at the start of their careers were promised anonymity, advances in DNA technology and the rise of ancestry websites threaten their secret and many are afraid they will be outed.

Doctor X said they were concerned there was still a stigma surrounding sperm donation and were worried for their reputations and medical practices.

“These days people get gift vouchers for sites like ancestry.com to track their family trees,” he said.

“For us, those vouchers have the potential to blow up lives. Anyone could get a knock on the door or a Facebook message out of the blue saying ‘Hi you are my dad’.

The doctor said he donated as a student for no other reason than wanting to help couples who struggled with infertility.

“It was a private, individual thing,” he said. “It’s not like I went with a crowd of my mates and we patted ourselves on the back and said ‘Aren’t we great, let’s get a beer’. When we donated the only real paperwork was filling out a profile with things like colour of hair, eyes, height and ethnicity. There wasn’t really enough in that profile for parents to find out who you were. We believed it was anonymous and couldn’t have guessed that in our lifetimes there would be the technology available for anyone to track us down.”

The physician confirms he has a relationship with one donor child, now a grown-up with their own child.

That person found him through a DNA site.

He said he was unaware of how many children he could have conceived, as that was never disclosed to him.

“I just want to stay anonymous, not just to protect myself and my career, but mostly to protect the children I have helped produce who do not want to be outed,” he said.

But another Brisbane doctor, who also donated sperm as a UQ medical student in the same era, said the donors must face up to their responsibilities.

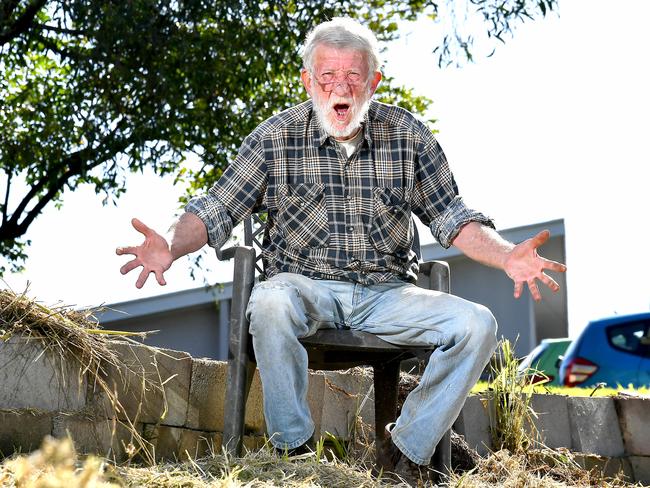

“As medical students we were happy to be a part of pioneering fertility medicine and today we can’t be selfish,” said Donald “Digger” Whittaker, who was united with a donor-conceived “sorta daughter” who had spent many tortuous years tracing him through a family tree.

“There is no need for blatant self-interest when it comes to providing the donor-conceived children with what they need to live their lives in peace.

“We were all intelligent medical men. I certainly knew that one day DNA science would cancel out any chance of secrecy.”

A University of Queensland spokeswoman said the university was not aware of any formal requests for sperm donations to students in the late 1970s and ’80s.

“For any UQ research, the current human research ethics approval process requires review of the appropriateness of the target participants and recruitment activities,” she said.

Dr Whittaker is one of many Queenslanders who backs a state government-run register where sperm, egg and embryo donors would be kept on record.

Currently, under the direction of Attorney-General and Minister for Justice Shannon Fentiman, the Legal Affairs and Safety Committee is looking into the benefits of a register and the extent to which identifying information about donors should be given to donor-conceived persons, while also taking donors’ right to privacy into consideration. The findings will be released in August.

“This kind of register is needed,” Dr Whittaker said.

“If the doctors are scared of a random knock on the door, then this kind of database would take away that shock factor.”

Doctor X said that if a database was formed, it should be a voluntary opt-in option for donors who believed they would be protected by anonymity and there should also be an opt-in clause for donor-conceived people to contact any siblings and their donor.

“But I believe that medical genetic and heritage data of the donor should be made available to the donor-conceived children when they turn 18,” he said. “The donor should also have access to information on the number of children conceived.”

The medic said there many things go through his mind when meeting a donor-conceived child.

“What will be the impact on my family, will they want me to meet their mother?” he said. “Will a long-term relationship develop, are there grandchildren, what if they asked for help, will your parent want to meet their grandchildren?”

The doctor freely admits he has loved meeting his “donor-conceived offspring”, who now has a child.

“The sperm donation thing has been bittersweet, but that is the part where it has been sweet,” he said.

Queensland University of Technology researcher Stephen Whyte has investigated sperm donation in the state and reports that well-educated young men, particularly medical students, are in high demand in the fertility industry. US colleges openly advertise in campus magazines for donors.

“It is an altruistic act for a man to donate his sperm,” he said. “It’s funny – if a woman donates her eggs she is considered to be kind and generous, but men who donate are considered as less giving. They are just w--king into a cup.”

It is believed there are up to 80,000 donor-conceived individuals in Australia and many now have their own children.