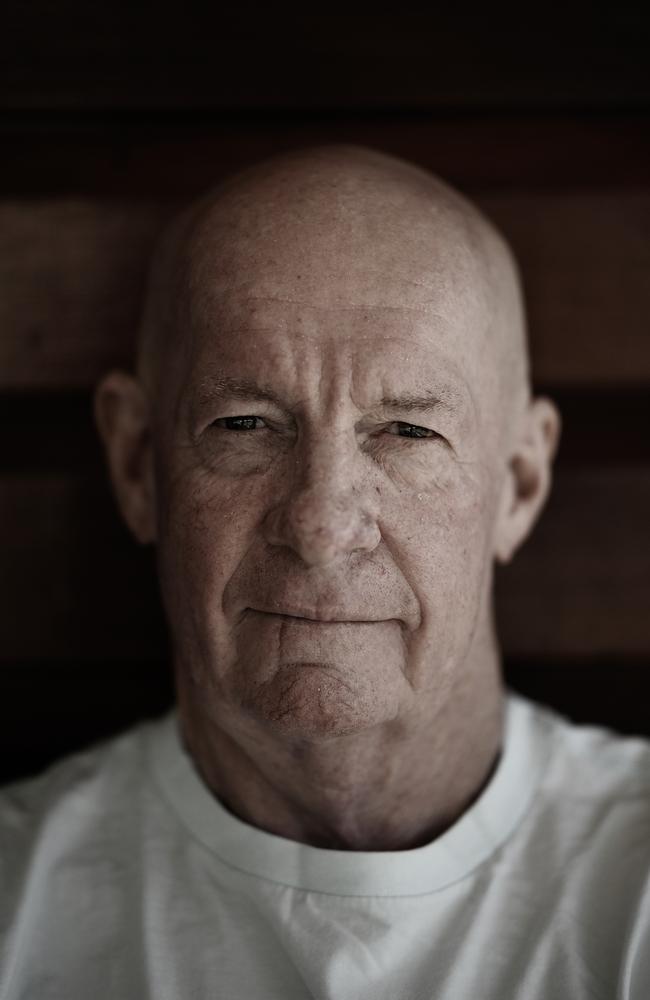

‘It’s a really violent place’: Gordon Nuttall reveals what really went on inside prison walls

Lisa says she will never forget the day her father’s verdict was read out in court. Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. On every charge

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Lisa Nuttall says she will never forget the day her father Gordon’s verdict was read out in court. Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. Guilty. On every charge.

She watched her father, sitting shell-shocked in the dock, gasp and stagger a little.

“I’ll never forget that day, I can close my eyes, I can smell that room, I can see the colours,” she says.

As the verdicts were read out, she burst into tears. She says that moment – just after 4pm on July 15, 2009, in Brisbane’s District Court – still haunts her.

“I’ll never forget the sound my dad made, because he was in the dock area, and we were just behind him, and I just collapsed on the chairs, and they had to take me out,” she says.

“I can still see those 12 people and when the foreman said guilty, he had to say it so many times.”

By the end of the court hearing, the word guilty had been uttered 36 times.

Gordon Nuttall, a minister in Peter Beattie’s Labor state government, was the subject of an extensive Crime and Misconduct Commission investigation and charged with taking secret commissions and official corruption over loans totalling $300,000 he had received from mining magnate Ken Talbot and another $60,000 from barrister and miner Harold Shand.

The day he was found guilty in court is a painful memory for Lisa, and for her father.

As he was led away by guards, Nuttall told his family: “I love you all.”

He was sentenced to seven years jail. At a second trial in 2010 he was found guilty of five additional counts of official corruption over another $150,000, as well as perjury, and sentenced to another seven years to be served cumulatively with his original sentence.

Now, 14 years later and a free man, the shock of those sentences is still raw.

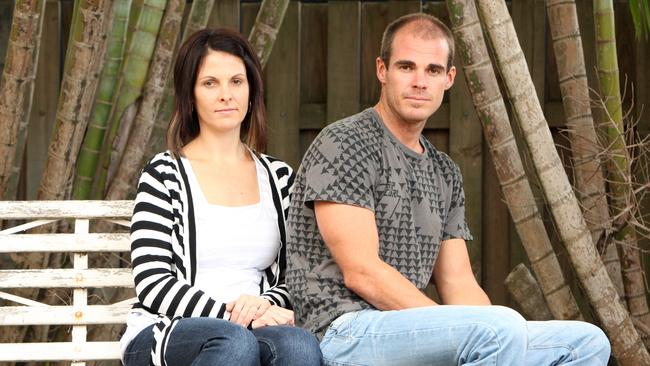

Lisa, now 48, has never spoken publicly about the events surrounding her father’s conviction and imprisonment. Sitting in her modest suburban north Brisbane brick home, she closes her eyes when asked how she’s been affected by her father’s jail time.

“I still have so much trauma. I have flashbacks every single day, even this morning I felt sick,” she says.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t remember something.”

Nuttall told investigators that the Talbot money was a loan to help buy properties for his three children, Lisa, Andrew and Kim, so they could get into the housing market. There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing by Nuttall’s family.

Andrew, now 44, says his dad paid a terrible price.

“When they took him away, they took, not only our father but our best friend and that’s what killed me the most,” he says.

“My mate was gone, and I couldn’t just go over and see him.

“I couldn’t just give him a call and ask him for some advice or talk, shoot the breeze about the football or the cricket or what was going on and that was all gone. It was totally gone.”

Lisa says to this day the imprisonment of their father continues to take a significant toll on all of the siblings’ physical and mental health.

“I struggle with a lot of anxiety and depression. There’s a lot of complex trauma there. I was very thin for a long time when Dad was away. Just stress,” she says.

Andrew was so depressed he had to quit work.

“I couldn’t get out of bed, struggled to eat any food. I lost a lot of weight, I was down to 76 kilos, skin and bones basically,” he says.

After Nuttall was sentenced, he was immediately taken to the Wolston maximum security jail at Wacol, in Brisbane’s south-west.

He was stunned to have gone from sitting around the cabinet table to a jail cell or, in his words, from “the penthouse to the shithouse”.

He says the threat of violence was constant, day and night.

“You’re chucked in with the worst of the worst, I was in with some terrible, terrible people, like really bad people and you’re treated exactly the same as them because you’re in a maximum-security prison,” Nuttall says.

There were lots of tears in his new confined living quarters.

“I think the hardest part was dealing with the enormity of the sentence. When I first went in, I just could not see past the horizon; I just thought, I’m not going to make it,” he says.

“I honestly didn’t think I would make it. It was a day-by-day thing. Every morning I’d wake up and pray to make it through.”

Nuttall said he had to learn fast the “rules” of life inside maximum security.

“I quickly realised that the way to survive is – you know nothing, you see nothing, and you mind your own business,” he says.

Nuttall watched on in horror as a former Qantas pilot jailed over drug offences learnt that lesson the hard way.

“He walked past these two blokes playing chess and he said, ‘I wouldn’t have made that move’, the bloke jumped up and shattered his jaw,” he says. “So, it’s a violent place, it’s a really violent place and people forget that.”

On one occasion he accidentally put his own life in danger. He pauses as he relives the memory.

“I was at the gym, and I’d found these old lawn bowls; they had chunks out of ’em but I cleaned them up,” he says.

“This fella came charging in to get one and I said, ‘Hang on, hang on’ and I didn’t realise this, but he’d picked one up and he was gonna bash me on the back of the head with it.

“One of the other boys that I got on with stopped him and he told me, ‘You need to be more mindful around you and your surroundings Gordon, you went really close’. He said ‘that could have got ya killed’.”

Nuttall says he struggles to understand why he was kept in maximum security for so long when other politicians sent to jail for similar offences were either out on parole earlier or sent to the low-security Palen Creek prison farm at Rathdowney, 100km south-west of Brisbane.

“I’ve got to let it go but someone, somewhere, stopped me going to the farm,” he says.

“Because when I did eventually get there, one of the officers said to me, ‘your file came here years ago, and we were expecting you, but it was pulled at the last minute’.”

Nuttall would spend more than five years in maximum security.

“What I never understood was why they kept me there. Why? To punish me more?” he says.

“My view is that they didn’t want the perception that I was getting any favours and they didn’t want any media around that.”

The nightmares from his extended stay in maximum security persist to this day.

“It’s very hard to escape the misery and find a happy place. It’s nearly impossible to find somewhere where it’s quiet because in your cell, there is a speaker in-built into the wall and that thing never shuts up,” he says.

“I used to get toilet paper, soak it in water and stick it over the speaker to try and cut the noise out. You’re not allowed to do that but now that I’m free, they can’t come and get me.

“There was nowhere to go. Nowhere for peace, nowhere to go for some quiet even at night, you know, guys are screaming and all that sort of stuff. So, it’s very hard to escape that bubble of misery.”

Lisa was terrified for her father’s welfare when he was in maximum security.

“I was worried that he would do something to himself in there. That was my concern,” she says.

“One day we visited him and he was empty. He’d been in just over a year, and in his eyes he was just empty and he was really sad that day. I just had a feeling and I can close my eyes and see the scene.

“I hugged him and said ‘please don’t do anything stupid’ and he said to me that he was thinking about it at that point and that visit changed his mind.”

Family visits with six of his grandchildren (aged 4 to 10) kept him going, but there was a downside after they had left.

“When you’ve got to go back to your cell that’s when it really hits you,” he says.

“I couldn’t tell you the number of times I cried and broke down in my cell on my own. Because before and after the visit you get strip searched and, you know, it’s humiliating, it is really humiliating.”

Eventually a guard warned Lisa to stop bringing her young children to visit their grandfather because of the other prisoners.

Nuttall eventually made it to Palen Creek prison farm and recalls the wonder of being able to pat a horse, the first physical contact he’d had with another living thing in more than five years.

“And then I went for a walk, and I picked up a leaf from under a tree and I held it in my hand, and I hadn’t done that in five years,” he says. “And it was the simple things – tiny little things like that.”

When Nuttall was finally paroled on July 20, 2015, even the boss of the facility wasn’t officially told.

“He called me down to his office and was a bit embarrassed that he’d heard about my impending release on the radio news,” he says.

The secret operation to sneak the high-profile inmate past the waiting media outside the prison farm gates and into the arms of his family was code-named “Gumnut”. It was a success, with reporters and camera crews hoodwinked and Nuttall making it into Lisa’s car outside the Beaudesert Post Office.

Lisa describes it as “the best day”.

Unfortunately, the winds of fate weren’t done with Gordon Nuttall.

Just six weeks out from the end of his 14-year sentence in July this year, he noticed a lump in his neck while shaving. A biopsy was sent for testing.

The results were not good. He has stage four kidney cancer that has already spread to the lymph nodes in his neck.

“I just cried and cried and cried,” Lisa says of finding out the diagnosis.

“But it is still unfair. It’s just shit. It’s shit because we finally got him back and who knows what will happen now, because it’s not good.”

Nuttall has completed three courses of immunotherapy treatments at Bundaberg’s Friendly Society Private Hospital.

He is now living in Woodgate, 55km south of Bundaberg, and is optimistic about the future.

But the cancer diagnosis coming so close to the end of his sentence seems particularly cruel to son Andrew.

“As ad told me, my whole body just basically slumped and sunk, I thought, what, not again and I cried. I sat in my office at work and cried,” he says.

“But about an hour later I thought to myself you know what? Stuff this. Dad has been through hell and back, this cancer is a walk in the park.

“We will get through this and come out the other side again.”

Lisa says she’s learnt to value every minute she gets to spend with her father.

“I’m hopeful that he’s still got some good years left in him,” she says.

The large tumour is pushing on Nuttall’s diaphragm, giving him a regular cough. But despite all that, he feels like a free man. “I’ve had a life, you know, I’m 70 and sure I’ve had a few hiccups along the way,” he laughs. “I’ve had a good life and I’m surrounded by a beautiful family, some really close friends and lots of mates.”

He now has 12 grandchildren to dote on.

“With all that support around you, you kind of just say I’ll take it in my stride and now the goal is to get to 80,” he says.

If he had his time again Nuttall knows he would have done things differently, and would not have asked Talbot and Shand for the money.

“No, it just wasn’t worth it,” he says.

The moment his sentence expired – after 5113 days, at midnight on July 13 this year – was a good one, celebrated with partner Jane Herd-Evans.

“My partner Jane and I got up just before midnight and had a rum or two and a party pie,” he says.

“It’s been a long journey and a very painful one, but it’s over so we’re looking forward to new horizons.”

The pair met at the Woodgate bowls club five years ago.

Herd-Evans, 64, works as a medical secretary at I-Med Radiology in Bundaberg so has an insight into the treatment Nuttall is going through for his cancer.

Most days, Nuttall can be found at the Woodgate bowls club, located on Kangaroo Court. The street name makes him laugh.

You can find him drinking a beer, playing a game, chatting to the locals. Nuttall is the reigning singles champion – a title he’s won for the past two years.

He insists he isn’t trying to rewrite history.

“All I want to do is tell people how it really happened and sometimes that’s very hard when you’re in the witness box and you can only answer the questions that are put to you. I was just a dad who wanted to get his kids into a home,” he says.

“When I was away it was horrible. Very hard. You cannot forget it. It changes you as a person in a big way.

“I’m far, far more appreciative every day of being able to see the ocean and go for a swim and having family and friends around and living life. You appreciate all that so much more.”