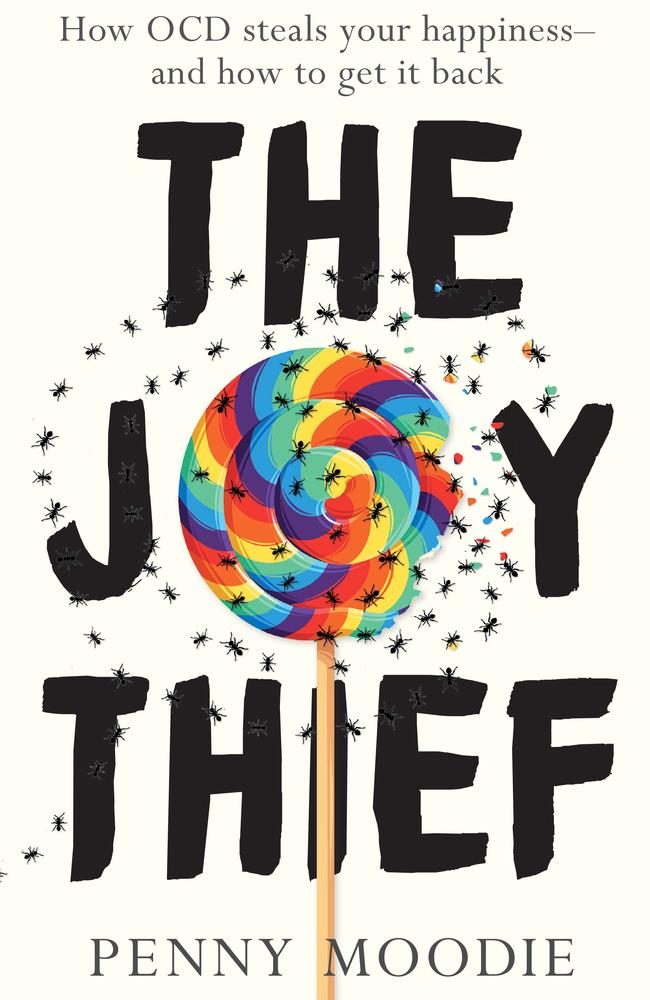

‘It took me until 31 to get an OCD diagnosis’: Penny Moodie reveals common symptoms she learnt to live with

Penny Moodie has battled OCD since she was a child. In a new book, she reveals how she learnt to treat her disorder and find love and happiness with husband Hugh van Cuylenburg.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s thought that there are two “kinds” of obsessive-compulsive disorder when it comes to the course of the illness: chronic and episodic. Someone with chronic OCD will generally always experience some level of symptoms, even if the severity fluctuates. Episodic OCD only presents for a certain amount of time and is then followed by a period when symptoms disappear, with or without treatment.

Most presentations of OCD are chronic, and many people with chronic OCD experience symptoms that wax and wane over time for various reasons.

A study carried out in 2021 investigated why the severity of OCD symptoms seems to ebb and flow throughout the day. It looked at a person’s chronotype (whether they’re a morning person or a night owl) and how their symptoms presented over a seven-day period. It found that during times of higher alertness, the person experienced a reduction in their symptoms. So, those who function best in the mornings tended to experience worsening symptoms at night when their alertness levels were compromised.

This sounds straightforward and logical, but it can help to be mindful of when OCD symptoms are likely to flare up or settle down.

Another recent study looked at symptom fluctuation in anxiety disorders (including OCD) during the menstrual cycle. Interestingly, it suggests that for people with OCD and post-traumatic stress disorder, the perimenstrual period – from roughly the week prior to the week following menstruation – can be a time of heightened vulnerability to anxiety symptoms. This is thought to be due to fluctuating hormone levels.

Clinical psychologist Dr Andrea Wallace suggests that OCD tends to peak when things such as stress and sleep deprivation are in play. She also notes that certain OCD themes can coincide with significant life events, causing OCD symptoms to flare up.

“People tend to have particular themes that are problematic, such as having an overdeveloped sense of responsibility. So, events that are associated with those themes – for example, living through a pandemic or having a baby – can cause OCD to peak,” she explains.

At the end of the day, however, Dr Wallace highlights the fact that wherever compulsions are performed, OCD will be found.

And while it can be helpful to be aware of the things that might exacerbate your symptoms, the OCD flame will continue to burn as long as compulsions are fuelling it.

“For instance, if a new parent begins to perform compulsions in response to their unwanted intrusive thoughts, OCD symptoms will increase. If they drop the compulsions, the symptoms will drop away,” she says.

A NEW LOVE

Hugh and I first reconnected a few weeks after I returned from living and working in Geneva for six months. I’d briefly dated Hugh’s brother, Josh, in high school and had bumped into Hugh a few times over the years.

After chatting on Facebook Messenger over the previous few months, Hugh and I decided to meet up at a cafe in Melbourne’s inner north. The catch-up was organised under the pretence of a work opportunity, which was real, but I think that we both knew – or at least hoped – there was real chemistry between us.

Hugh arrived about 15 minutes after me, and I noticed that he had the same slightly lopsided, swaggering gait as his brother. He had a beaming smile and plonked himself on the chair next to me. Not only did I feel immediately at ease, but I also knew that I wanted to spend more time with this man. I felt an instant connection and attraction to him. We talked about the job he thought I should apply for, with my background in health communication, but before long we were chatting about everything from cricket to meditation. The conversation flowed so effortlessly, and we both quickly realised that we found the same things funny. I wasn’t forcing laughs at his jokes; he genuinely had me in stitches. I knew then that I needed to be with someone who made my diaphragm ache from laughing.

Both of us left the cafe unsure of what the future held, but certain of the fact that we would see each other again.

Fast-forward about two weeks, and Hugh and I were spending almost every day together. I’d been invited to apply for a permanent job at the organisation I was working for in Geneva, but the thought of being away from Hugh seemed unfathomable. He invited me to join his family holiday … where I met his parents. We all awkwardly made jokes about the fact that I used to date Hugh’s brother when I was 14 years old. I was particularly keen to impress Hugh’s mum, Liz. Her three kids were her world, and she was the moon orbiting around them, never interfering but unfailingly present in their lives. It didn’t take long for her, along with the rest of Hugh’s family, to quickly accept me into their universe.

Over the next few months, I felt so giddy with love and fulfilment that I started to wonder why I was still taking the little white pills every morning. I hadn’t been racked with obsessions for almost a year and, while I often felt anxious, those feelings seemed to pale in comparison to the torture of obsessions, so I felt like it was all manageable.

I hated the idea of being on medication for my whole life, and I’d convinced myself that if I went off the sertraline (Zoloft), I’d regain the career ambitions that had dissipated after the first month of being medicated. For the last year I had cut down to half the dosage I was originally on, and things hadn’t fallen apart. I wasn’t seeing a psychologist or a psychiatrist, but I was in love! And love conquers all!

Or so I thought. I went from taking 25 milligrams of sertraline every day, which is a very low dose, to taking nothing at all. After a few months, I realised how much those tablets were doing for me.

The first few months were manageable.

I’d getregular “brain zaps” or sudden feelings of vertigo throughout the day, but I was expecting those. After all, I’d googled “What to expect after going off antidepressants” plenty of times. What I conveniently ignored was the clear warning that suddenly stopping antidepressants can be life-threatening.

But considering that many adults with OCD take up to 200 milligrams of sertraline per day, I didn’t think that 25 milligrams was enough to really affect me if I wasn’t on it.

I’d been taking the pills for almost eight years at that point, though, and my brain had become accustomed to a higher level of serotonin. I started noticing little things creeping back into my routines that were annoying but didn’t really bother me at first.

When I was driving, I’d wonder what it would be like if I shut my eyes for a second. I’d try it. Then I’d wonder what would happen if I shut them for two seconds. I didn’t want to do it, but I couldn’t stop wondering what would happen, so I thought it would just be easier if I did it. But then I’d have to do it again and again, for slightly longer periods each time. It sounds idiotic, and dangerous. I didn’t have any kind of death wish, and it’s a difficult compulsion to explain, but I couldn’t stop. I’d also regularly clench my jaw, even though – or perhaps because – it was very uncomfortable and hurt my teeth. But again, my brain wouldn’t let me stop.

Hugh noticed my anxiety returning when I woke up at his place one morning feeling particularly irritable and slightly panicked. We’d planned to go out for breakfast at a nearby cafe in Fitzroy with two of his best friends, whom I’d never met, and I said that I’d drive. Almost as soon as I got out of the garage, I mounted a traffic island in the middle of the road, which I swear I’d never seen before. Hugh looked terrified to be in the car with me, but he decided not to say anything.

When we got to the cafe and were being shown to our table, I knocked over a glass jar filled with sugar that I hadn’t noticed in my peripheral vision. It was a chaotic entrance, and the sort of thing I’d usually laugh off. But I felt flustered and annoyed at my clumsiness, and I quickly excused myself from the catch-up, explaining to Hugh’s friends that I had a migraine.

ANXIETY AND THE BRAIN’S RESPONSE

What I didn’t realise was that, in my highstate of anxiety, my brain couldn’t differentiate between stress and danger, so it began shutting off the parts that I didn’t need for “survival”, such as the frontal lobe. Energy could then be redirected to my limbic system (emotional brain) and my brain stem (survival brain).

That’s why I was crashing into things, knocking things off tables and just generally feeling like my faculties were out of control.

If I’d had more insight back then, I’d have spent some time during these episodes calming my limbic system through conscious breathing, exercise or simply validating my feelings.