‘I was dead for 22 minutes’: What I learnt about life from dying

Chelsea Adcock had just finished a high-intensity gym class when her heart stopped beating. This is her extraordinary tale of survival. SEE THE VIDEO

It’s been a long, hot Monday and walking through the front door of her family’s home late that November afternoon in 2020, the last thing Chelsea Adcock feels like doing is dragging herself to the gym. Hours of unloading, stacking food and crushing boxes at the Fortitude Valley homeless shelter where she works has left her exhausted.

She says as much to her mother Michelle, who gently encourages Chelsea to continue the fitness routine she’d put in place to feel her best for her recent 22nd birthday pool party.

There are about 20 people in the high-intensity interval training (HIIT) class at Jindalee Fitness 24/7 in Brisbane’s western suburbs. Dynamic personal trainer Wayne Westwood, now 55, dances and shouts encouragement over the pumping tunes, pushing each of his sweaty charges to get the most out of the demanding session. Hauling a 10kg weighted bag on her back through a set of walking lunges towards the end of the class, Chelsea starts to feel light-headed and faint. She drops the bag and moves to sit down.

As inky blackness swiftly closes in, she doesn’t see Westwood approach her in concern, doesn’t register the foam bubbling from her mouth, doesn’t wince at the sharp pain as she bites her lip slumping to the floor.

In less than a minute, Chelsea’s heart falters and stops beating, her lungs falter.

The fit, active and healthy young woman, newly in love and popular with wide circles of friends, effectively dies.

What unfolds next amid the desperate chaos is nothing short of a miracle. And neither Chelsea nor her family and friends will ever be the same again.

Answering the call from gym employee and close family friend Steven Bratton, Michelle initially thought he meant Chelsea had fainted, dehydrated, when he urged her to come quickly.

“OK, Steven, OK, I’ll be there. He said, ‘no, Michelle, it’s more than that, she’s not breathing’.’’

He’d barely finished speaking before she was bolting out the door. Driving the short distance from their Fig Tree Pocket home, a frantic Michelle, 58, could hear ambulance sirens racing up the Centenary Highway behind her.

Bratton, 28, had been packing up to go home after a massive sales day when two women alerted him and a colleague to the unfolding drama. They arrive in the gym room, called The Dungeon, in time to see Chelsea crumple. Westwood and another class member start CPR. Triple-0 dispatcher April Cooper guides them through use of the gym’s Automated External Defibrillator (AED), already attached to an unconscious Chelsea’s chest.

After ringing Michelle, Bratton follows his compulsory first aid training and heads outside ready to direct paramedics. He sees two QAS vehicles in front of a cafe across the carpark,

and thinking they have the wrong address, he rushes over.

In a stroke of luck, critical care paramedic Jason Jones, one of a small number of specially qualified officers, and paramedic Benjamin Baxter are discussing a patient who had collapsed and was initially thought to have suffered a serious episode. Baxter and a colleague plan to take that patient to hospital and then head home after a 12-hour shift, while Jones will drive his 4WD back to his station. Then Bratton “quite calmly” approaches and tells them of the unfolding emergency.

“Benjamin and I jumped into the 4WD and drove all of 30 seconds maximum, if that, across the carpark to the front of the gym, grabbed all my gear – probably four or five kits needed to do a resuscitation – and headed in past all these guys doing workouts in front of the mirrors. It didn’t occur to us this was a real case until we turned around the corner and saw the young lady on the floor. I knew straight away she was in cardiac arrest, [recognised] that ineffective breathing pattern,’’ says Jones, 45, who has three daughters, the eldest not much younger than Chelsea.

Met by Bratton, Michelle was confronted with the sight of now four paramedics working on her prone daughter, “clothes ripped off, all exposed, and there were just like needles flying through the air, and pieces of whatever they were using’’.

Jones asks if Chelsea had any underlying conditions or was taking any medication, then reassures her they are doing everything possible. Someone sits her down outside the room, comforts her, presses a bottle of water into her shaking hands.

Bratton escorts Michelle’s newly arrived husband Jason, 56, to her side. “I said to Steven, she can’t die tonight, so please go over there and tell me she’s OK and that she’s breathing,” Michelle tearfully recalls.

“Please, I begged him. He kept going in and coming out with a really grim look on his face.”

An equally emotional Jason, a real estate agent and auctioneer, describes making a fervent promise in that moment that if Chelsea survives, he will do whatever it takes to be a better man.

Blood trickles from Chelsea’s mouth as her sternum cracks under the force of controlled compressions. The AED is removed and her heart shocked with QAS equipment “for three or four rounds from memory. Even during chest compressions, she had really good colour, the same sort of [limited] breathing effort. She was actually groaning during compressions, which might sound awful for her, but it’s actually a really good sign that there’s enough blood flow to the brain for her to feel pain, even though the heart is not pumping itself. That spurs us on even more but also, she’s young, she works out, she’s fit-looking,’’ says Jones, a specialist with 24 years’ experience.

Twenty-two minutes. That’s how long it takes to get Chelsea’s heart pumping, her lungs inflating again, normally, on their own. An eternity in each and every one of those 1320 seconds for her desperate parents.

Bustled onto the gurney and into the ambulance, Chelsea’s pulse is strong, her colour good. There was no need for the skills of QAS’s High Acuity Response Unit (HARU), which Jones had called as the next contingency.

“Her level of consciousness was that high, when I asked her about her name, she had the presence of mind to pay out on me. I actually can’t recall what she said, but it was enough to make others laugh. That typical cheekiness of a young person, which was lovely, and I was happy to take that,’’ he grins.

Closely following the ambulance, Jason and Michelle, joined soon after by eldest daughter Holly, 26, wait another eternity in the Royal Brisbane Women’s Hospital emergency department before they can finally see Chelsea, kiss her forehead, grasp her hand.

“We were just in total shock, just praying and hoping that she was going to be OK, that she would pull through. We didn’t give a shit about [seeing her covered in tubes, hooked up to machines], all we cared about was that she was alive,’’ says Jason, his booming auctioneer’s voice cracking.

Sudden cardiac arrest is when the heart stops beating, rendering the patient unconscious and unable to breathe normally, if at all. It differs from a heart attack, where the patient is usually alert, breathing and complaining of chest pain.

The Heart Foundation estimates about 25,000 Australians have a sudden cardiac arrest outside of hospital each year but as few as five per cent survive.

Yet here is Chelsea, sore but alive and managing to smile, surrounded by flowers and balloons, getting to know her cardiac care ward mates, dipping into a James Patterson murder mystery and Simpsons comics.

The psychology graduate initially wakes, unable to move her legs for several hours and essentially blind for two days, but recovers to walk out of the hospital after eight days.

Heart Foundation CEO and cardiologist Professor Garry Jennings says sudden cardiac arrest in young people occurs at a rate of one to two per 100,000 annually, with studies showing about 15 per cent happen during or immediately after exercise. There is no single or common cause, with 40 per cent of sudden cardiac deaths unexplained even after autopsy.

While unable to comment on the specifics of Chelsea’s case, Jennings says her recovery highlights the importance of CPR and community access to AEDs, which increases survival rates to almost 90 per cent if accessed within two to five minutes.

“There’s no questioning that she was in an absolutely life-threatening situation and if she hadn’t had that care around her, and the AED, she wouldn’t be with us today,’’ he says.

Jones goes a step further to describe Chelsea’s recovery as “absolutely exceptional”.

“That gym staff played a key role, I’ll tell you now. They’re the ones that bought her time. Chest compressions don’t solve a problem, they buy time; they keep some blood flowing around the body … to key organs, namely the brain, heart, lungs et cetera,’’ he says.

Which leads us to the question, why? Why would a healthy young woman with no symptoms, one who was required to regularly record normal ECGs and blood tests to access specific medication for her mental health, have a cardiac arrest?

Extensive testing pointed to the uncommon hereditary genetic heart condition arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) and long QTs, a heart rhythm disorder which can cause fast, chaotic heartbeats.

ARVC causes fat and scar tissue to replace normal muscle on the right side of the heart, leading to rhythm irregularities or enlargement which prevents efficient pumping. The diagnosis had to be confirmed by genetic testing, the results received from the US six months later. A battery of tests shows Jason, Michelle and Holly are healthy, though they’re still waiting to access conclusive genetic testing.

“The rates commonly quoted (around ARVC) are between two and five per 1000 in the population, the peak age is about 30 years, and it is being increasingly recognised in recent years ... with the development of more sophisticated (diagnostic and imaging) techniques,’’ says Jennings.

“It’s a funny condition in that it’s genetic but you rarely see it in babies or young kids, which suggests it appears (over time) rather than being present at birth. Even when it’s serious enough to cause sudden cardiac arrest – as it has on this occasion – not all people will have experienced any symptoms beforehand.’’

Jennings says Australia’s first national summit on sudden cardiac arrest, considered

to be under-researched, to identify ways to improve knowledge, prevention measures

and survival rates will be held in Canberra in June.

Chelsea pulls aside the neckline of her dress to reveal a faint scar under her left collarbone. “I asked when I’m going to have a cardiac arrest again and [doctors] don’t know if I am, or how I am, or when I’m going to have it, so on the seventh day [in hospital] I got my ICD [implantable cardioverter defibrillator] implanted … now I’m like Iron Man.’’

As well as the ICD, which detects and resets irregular heartbeats, Chelsea, now 23, will sleep with a bedside monitor, which registers and automatically reports any irregularities to the RBWH, for the rest of her life. Three-monthly check-ups have been reduced to six-monthly and medication for her mental health altered. She has joined an online support group for sudden cardiac arrest survivors and sees her psychiatrist monthly.

“It was weird because I had just had this massive thing happen to me – I had died for 22 minutes – and then I went home. I was like, what now? I had no idea what to do with myself. I couldn’t exercise, I couldn’t work, I couldn’t drive for six months. I was really reliant on Riley. He was my only source of happiness.’’

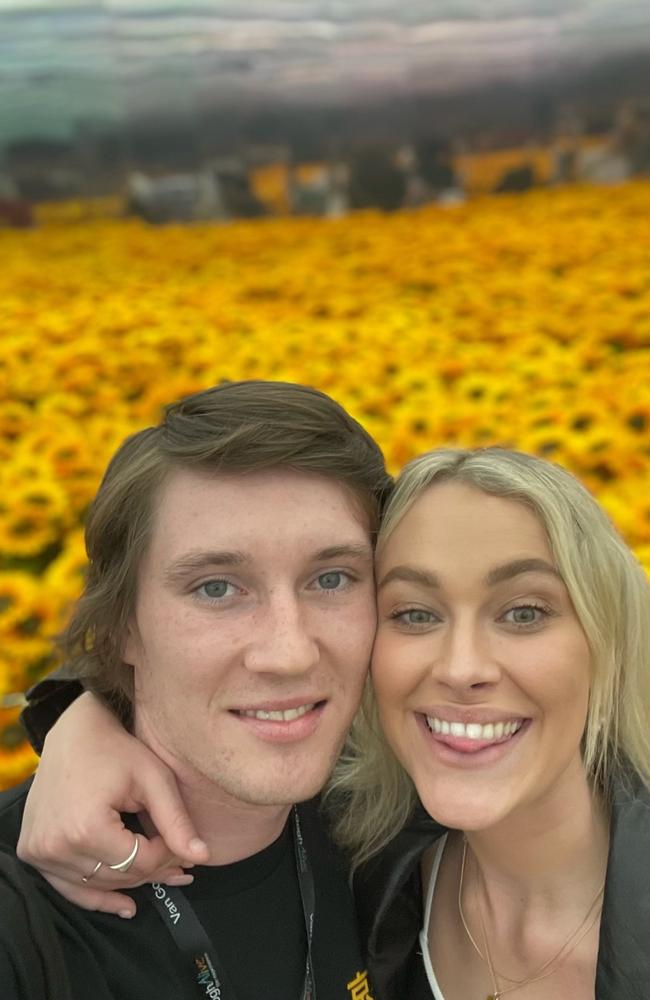

Riley Hamilton didn’t quite make the impression he’d hoped when he walked into Chelsea’s 21st celebrations in 2019, invited at the request of his best mate, the boyfriend of Chelsea’s best friend.

“I was like, who is this guy at my party? I didn’t really like him when we first met. He was obnoxious and wearing this watermelon T-shirt and matching pants. But he was really funny,’’ grins Chelsea.

Fast forward to October 2020 and her 22nd birthday pool party. “We started talking and I was like, I really like this guy. We spoke at another party the next weekend, then he messaged me and was like, do you want to go on a date with me? I said, okay.

“We went to Fat Angel in [Fortitude] Valley and he was so nervous. He’d had two shots before I got there. By the end of the night, he was pretty drunk and was like, I really like you, blah blah blah, went on this massive spiel, and we’ve been dating ever since.’’

A whirlwind two weeks after that first date, Hamilton was becoming increasingly concerned as his messages went unanswered. Then Michelle rang to let him know what had happened.

“My world tipped upside down. My heart and stomach sank. All I wanted to do was make sure she was OK and stable,” he says.

Every night Hamilton, 24, would hire an e-scooter to ride from the city bar he managed to be by Chelsea’s bedside, staying as long as he was able.

“I would have to go on bathroom breaks at work to cry. It was super-confronting, seeing all the wires and how uncomfortable she was. Her being the youngest person [in the cardiac care ward] by 20 years or more was pretty scary,’’ he recalls.

“I would sit there until she fell asleep, I’d get her snacks. She was already friends with most of the people in the cardiac area, saying hello to everyone in the rec area. All the different pacemakers were framed on the wall and she’s like, that one is in my heart now. Having such a negative thing happen to her, she’d still be positive and making friends, even in hospital.’’

Jason and Michelle say their family has been blessed by two angels – Bratton for finding the paramedics in the carpark and Hamilton for supporting their girl “through her absolute darkest days … better than any psychiatrist or psychologist”.

Struggling to process what had happened and limited to bed rest, couch and TV, their youngest was depressed, frustrated and confused, often lashing out in anger, only to tearfully

apologise later.

“I would make her laugh, even when I wasn’t funny, and it was just me being laughed at. Her parents would be a wall away from her bedroom, watching TV in the living room, and would always hear Chelsea laughing and screaming, so it was good to know they could hear her still having fun and happy,” says Hamilton, who swapped creative arts studies for a hospitality management career.

“She’s the bravest person I’ve ever met and the most resilient. This could happen to anyone and you could fall into such a dark pit of depression. I like to think I helped her through it but she has her own willpower, she would have got through it with or without me.

“My heart already knew Chelsea was ‘the one’ before the accident, but my mind didn’t. When it happened and I almost lost her, I knew I couldn’t lose her again. I just want to be with her for the rest of my life. She makes me happy, extremely happy.’’

The Brisbane River echoes with the cheers of raucous revellers dressed as dead celebrities as Chelsea – dressed as Marilyn Monroe – blows out the candles on her Happy Death Day cake, decorated with a heart and pulse line. There’s quiet as Jason, wearing an Elvis Presley costume, speaks, Michelle, dressed as late American actor Sharon Tate, by his and Chelsea’s side.

“Thank you ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, for coming here today to celebrate Chelsea’s rebirth day. She calls it ‘death day’, but she did not die … it’s exactly 12 months since Chelsea had a cardiac arrest,’’ says an emotional Jason.

“They say sometimes the best things in life are badly wrapped, well I can tell you, it was very badly wrapped, that particular gift … but the last 12 months have been magnificent for Chelsea and our family.’’

Chelsea is healthy, has joined Adcock Prestige and is happily making a home in Toowong with Hamilton and their new sphynx kitten Biggie Smalls. Holly, who blames a lack of confidence for flirting with several careers, is now firmly focused on becoming a real estate agent.

The family, particularly Chelsea and Holly, who had a “tumultuous” relationship previously, are the closest they’ve ever been. For Bratton, who drew laughs for donning a blonde wig and monogrammed gym T-shirt to attend the party as Chelsea herself, it took a while to feel comfortable at work and not startle at sirens. He says the experience ultimately drew him closer to family and friends.

The impact of that November 30, 2020 night has perhaps been most profound for Jason. While Michelle withdrew from work in the family business, her friends and regular life – concerned only with Chelsea’s recovery – Jason became a “crazy man’’, determined to keep the promise he made pleading for her life.

“I made a pact to myself that if she lived, I would be the best version of a person I could be, in my business life and personal life, and I was going to go hard,’’ says Jason, who flipped his first house aged 20, worked in jewellery and then owned the Contented Tummy restaurant in Graceville for years. He moved into real estate in late 1994, working for two national franchises before establishing Adcock Prestige in Taringa in 2002. Before Chelsea’s near-death experience, Jason only worked 25-30 hours a week. “It got to a stage where my wife was saying, ‘Jason, it’s noon and you’re watching Netflix, this isn’t right’,” he says.

Today, he’s up at 4am to exercise and work before heading into the office by 8am, where he puts in a full day then heads home for dinner by 6pm “every single night”.

He takes Michelle – with whom he’ll celebrate 32 years of marriage in September – out for dinner every Saturday.

The empty-nesters (except for dachshunds Hank and Eli) prioritise family gatherings and holidays several times a year. At Christmas, they donated $1000 to Cardiomyopathy Association of Australia.

“After I made that pact, I said I’m going to reinvigorate our brand and step it up. I threw everything out the window and started from scratch. We rebranded, I changed all technology, created an incredible website to make sure we can give an incredible customer experience, I brought these incredible, gifted young people on to the team … It got to the point my PA of 20 years, Sue [Moore] said, ‘Jason, what the frig are we changing this week?!’,’’ he laughed.

“I want to make sure we are the best at what we do, I’m setting a 10-year goal to make sure we are the go-to brand for prestige property in Brisbane and I want my family involved to create a legacy.’’

Michelle is director, Holly operations manager and digital marketing manager, and Chelsea human resources/support liaison, as part of a total staff of 11.

Chelsea sums up the family’s overall philosophy. “When I died, nothing happened like they said it would. My life didn’t flash before my eyes, I didn’t go to heaven, I didn’t go to hell, there was just darkness. The meaning to life is what you make it.’’