‘I felt there’s something not quite right’: Mat Rogers reveals son’s autism

Former NRL star Mat Rogers and his wife Chloe had suspected something was wrong for a while but that didn’t stop the shock from hitting when their son was finally given his diagnosis.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In December 2007, my family and I drive south to Woy Woy on the New South Wales Central Coast to spend a week over Christmas with Chloe’s dad and the rest of her extended family on the Maxwell side, including lots of little nieces and nephews running around. Max is now 19 months old and Phoenix three months.

A couple of days into our stay, Chloe and I notice Max spending an inordinate amount of time beside a dripping tap, transfixed by it. He is non-verbal but we’re not too concerned about that. We imagine he’ll talk when he wants to talk, and many of our friends and family members say the same thing.

On our last day, however, Michael, Chloe’s dad, pulls us aside and lays bare his concerns about Max. Years earlier, in his capacity as a barrister, Michael had worked on a case in which a single mother had suffocated her autistic child. Tragically, this mum just couldn’t cope any more. Preparing for the case, Michael did a lot of research into autism, including its symptoms, becoming something of a lay expert on the topic.

“I think Max is autistic,” Michael tells Chloe and me. “You really need to get him checked out.”

Chloe doesn’t react well. She hears her dad’s concerns as an attack on her perfect son. I understand her feelings, but I also feel there’s something not quite right about Max’s behaviour, something I cannot put my finger on. Maybe Michael’s wrong. I hope he is. But I know it would have taken a lot of courage for him to speak up.

Come the new year, Chloe and I start the process of exploring what could be behind Max’s unusual behaviour, which includes not having uttered a word by the age of 20 months. Our GP says he suspects Max may be on the spectrum but that it’s too early to make a diagnosis. Until Max is two, our best course is simply to see how things develop, he tells us. He also explains that if Max is ultimately diagnosed as autistic, there are plenty of things we can do to help him adapt. If he’s autistic, it means his brain is wired differently from the brains of non-autistic children, and as a result, he’ll need to learn differently.

Over the next couple of months, we take Max to see numerous professionals, but no doctor wants to diagnose him with anything just yet. Finally, after myriad appointments and tests, we end up with a preliminary diagnosis of PDD-NOS: pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. What the hell is that? I wonder. It seems to me to be the diagnosis you get when no one wants to give you a diagnosis, but they know something’s wrong.

For Chloe and me, the frustration and feeling of helplessness are mounting. Our problem is that until you have a meaningful, concrete diagnosis, you don’t know where to start in terms of treatment. I know as a footballer that I’m always much more relaxed about an injury when I know exactly what that injury is. Information is power. This thing with Max is like being blindfolded in a haunted house and told to find your way out. Chloe, whose life goal was to be a mum, feels as though she has failed somehow. All the time and love she’s invested into caring for our kids, and this is her reward. It feels so unfair, and I’m angry to the point of being bitter and twisted.

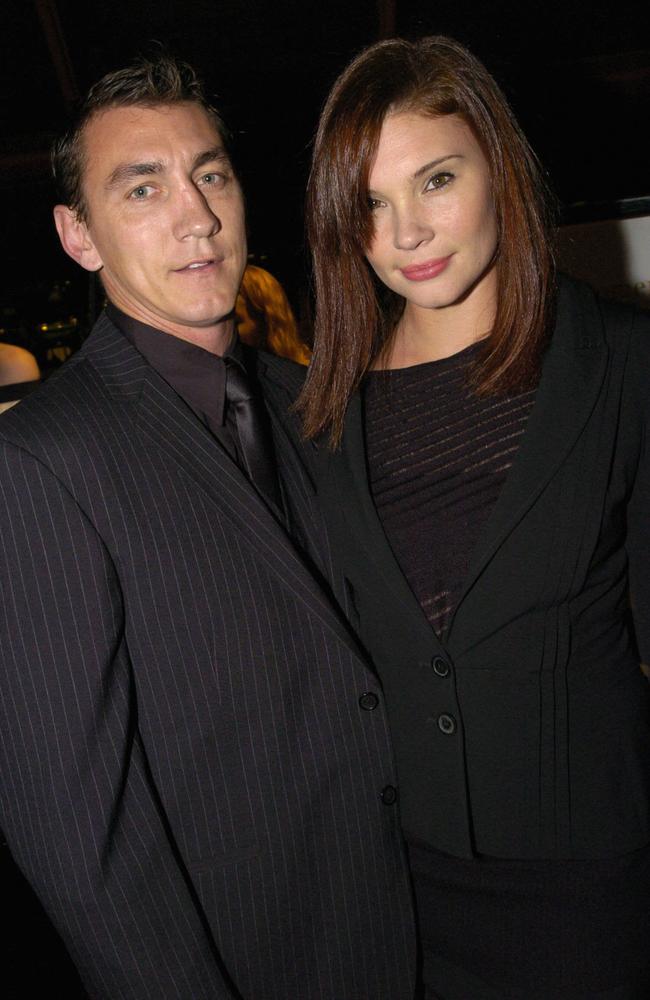

Although it’s a stressful time for us as Max undergoes all manner of tests and we sweat on the results, rather than tearing us apart, it draws us closer. I have never felt more in love with Chloe. She is passionately committed to our family, and it just doesn’t feel right that we’re not married. Our agent has nutted out a deal with a magazine to pay for our wedding later in the year, but the fact is I want to marry this woman now.

I ask Chloe for her thoughts, and we’re as one. We love each other too much, and have been through too much together, not to be connected by marriage. We are both Christians and don’t want to wait any longer. We need a win for us.

I ring the Titans chaplain, Pastor Russ Harmon, who’s booked to marry us later in the year. I explain that Chloe and I would like to be married immediately, but that no one can know. He agrees, but asks about the existing arrangement.

“You still need to do that one,” I say, “but we’ll just pretend to sign a marriage certificate”

I speak to my cousin Gavin, who I trust to be a witness and not to spill the beans. And on March 16, 2008, Chloe and I wed in a private – you might even say secret – ceremony, attended only by Pastor Russ, Gavin and his wife, Peta, and Max and Phoenix. It is beautiful. As we go through this traumatic time as a family, I want Chloe to know that I am all in, always. Marrying her makes me the happiest I’ve ever felt. Hearing the words “I do” come from her lips is confirmation that, together, we can overcome anything. There’s no crowd of people – and we don’t need one. There is us, and that’s all we need today.

The challenge now is to not tell a soul what we’ve done. We have a magazine contract to honour, as well as the hundreds of people we’ve already invited to the wedding. We’re not about to cancel that, and nor do we want to. We simply needed this private ceremony to galvanise us for the fight ahead.

About six months after seeing our GP, Max’s paediatrician finally diagnoses him with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Now the wheels may be about to fall off. I look at Chloe as the paediatrician is speaking and it’s as though the life has been sucked out of her. It feels like all the hopes and dreams we have for our son have been ripped away, that we’ve been sentenced to a lifetime of struggle.

Chloe breaks down, spending the next three days in bed. The stress of the previous six months, topped off by the diagnosis, has overwhelmed her defences. I’m shattered, but also confused about what this all means. Will Max ever be able to talk to us? Make friends? Play sport? Get married? My only reference point is the movie Rain Man. The Dustin Hoffman character … is that Max’s future self?

We hear about specialised centres within the school system that would help Max’s development, and about Autism Queensland information sessions, where we’ll be brought up to speed on the latest developments in therapies and meet other parents going through the same ordeal. We sign up for one and take ourselves along, feeling optimistic about what we’re going to hear. Chloe has come out of her state, having realised that if we can’t get ourselves together, what hope does our son have?

We walk into the information session, joining perhaps 20 other sets of parents. After half an hour, there’s a short recess, at which point Chloe and I leave and don’t go back. The information we’d heard was useful enough, but the parents make Al Bundy seem like an optimist – they are the most negative bunch of people I have ever been around. I get it: none of us has much to be happy about, but there isn’t a positive word spoken about anything Autism Queensland is doing. Rather, the meeting is just complaint after complaint about stuff that has little or nothing to do with why we’re there. Back in the car, Chloe and I agree that’s not an environment we want to be part of. We mightn’t know a lot about ASD, but we know this much: the life being painted by those miserable people is not the life we or our son are going to live. From that moment, Chloe becomes relentless in her study of ASD. What, she wants to know, are the next best steps for Max?

Though my life has been turned upside down (yet again), football doesn’t stop. I need to train, and I need to play. And I need to do both to a tip-top standard. Late in the 2008 season, however, I have to skip a few training sessions to attend various appointments related to Max. John Cartwright is understanding. Not so long ago he worked under the premiership-winning coach Ricky Stuart at the Sydney Roosters, and he tells me that Ricky also has an autistic child. He offers to tee up a phone call with Ricky and I grab at the chance to talk to someone I respect about what has become the most important subject in the world to me. Perhaps Ricky will be able to fast-forward the tape, so to speak, in terms of helping us give Max what he needs.

A short time later, Ricky’s on the line.

“It’ll all be okay,” he says reassuringly. “You need to find the thing that works for Max. There’ll be a thousand opinions, but you will know what works when you see the difference.”

A thousand opinions. Ain’t that the truth. Everyone has a thought or theory on causes, treatment or both. There are people telling us that Max must have watched too much TV; others say we’ve been feeding him the wrong foods. And, of course, the supposed evils of immunisation get an airing. When you’re at a loss about what to do, you find yourself tumbling down the rabbit hole time and again, just in case this latest crackpot idea you’re hearing about has even a skerrick of substance to it. It’s exhausting.

But Chloe and I refuse to sit on our hands, and enrol Max in the Early Childhood Development Program based at Burleigh Heads State School.

We start him at two days a week and monitor for any differences in his behaviour. When I walk into the place on Max’s first day, it seems to me the program has been set up in the school’s most dilapidated building. Sitting there, looking around me, it’s all I can do not to weep. These are the kids who need the most, I think, and yet they get the least. What the hell is going on? Is this our life now?

The blessing for us is that the centre is run by Jay Ohmsen, wife of Paul Ohmsen, the Gold Coast Titans doctor with whom I have a strong relationship. Jay has been working in special needs for many years and is a voice of measured reassurance at a time when we need precisely that. She’s a soothing contrast to the internet, which I’ve come to regard as a cesspit of witch doctors and con artists. Jay calms our frustration and anxiety, becoming our anchor in turbulent waters. Max’s behaviour doesn’t change drastically, but the mere fact of his being in the program gives us some comfort, as well as the confidence that he’s with people who can help him.