Tara Brown’s daughter doesn’t yet know truth about horror death

The day Tara Brown was hunted down by Lionel Patea is etched in the minds of many Queenslanders. But for her heartbroken family life must go on, some how. This is their story.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Most week days, after getting her granddaughter Aria off to school, Natalie Hinton heads to work at a domestic violence refuge. She sits in front of women who live in fear; for themselves, their children, their family, their pets. She tells them: “Never go back.”

Sometimes, as a woman’s story unfolds, if their resolve to break free of violence and control falters, Hinton, 56, will tell them who she is. That she is Tara Brown’s mother. “Most people remember Tara’s story,” she says. “Oh, I make them cry.”

Once you hear the story of Tara, how could you not?

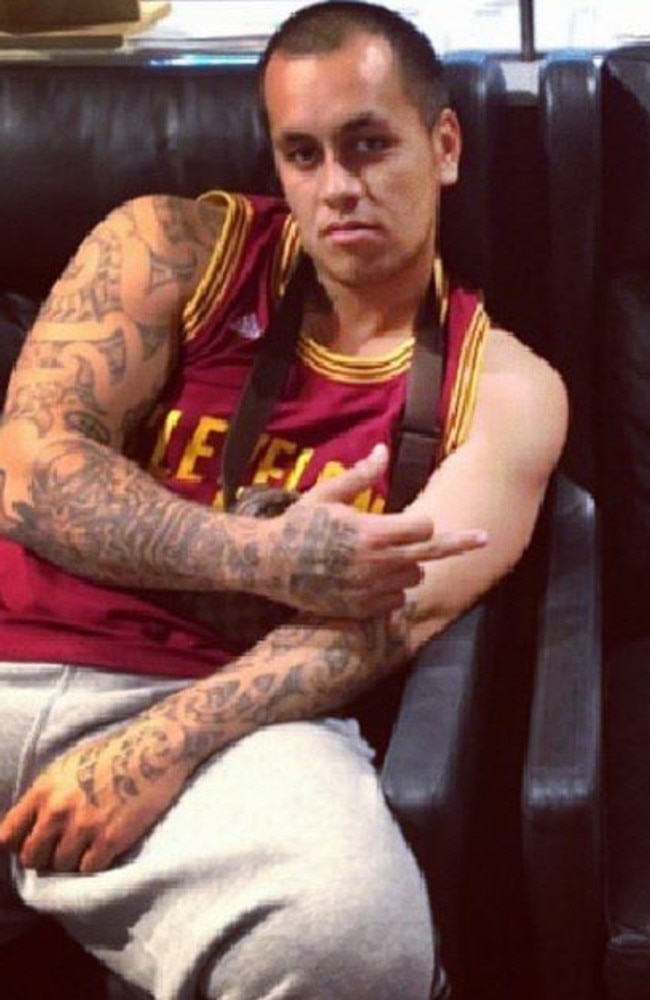

Tara Brown was 24 when she was pursued in her car through suburban streets of the Gold Coast by her raging, estranged partner Lionel Patea. Twice she was forced to stop at traffic lights; twice Patea, also 24, got out of his car and punched and pounded at hers. Terrified, Tara sped off, calling triple-0, begging for help.

Patea rammed the car. The impact, Tara’s blinding terror, the speed, led to her crashing the car, which rolled down an embankment, landing on the driver’s side. Tara’s legs were pinned but she was conscious. Neighbours rushed to help.

They did not know the thick-set, heavily tattooed man who arrived soon after. The big man who carried a 7.8kg solid steel fire hydrant cover that he put down at his feet.

All they knew was that he was helping them break the windscreen.

But Tara knew. She screamed, “Lionel! No!”

Patea picked up the hydrant cover. He leaned into the car. He struck Tara in the face with it. Again, and again.

The neighbours were stunned, unable to compute the viciousness before their eyes. Then, they did. They tried to stop him. Someone attempted a tackle; one woman jumped on Patea’s back. He threw them off.

Now Patea got inside the car. He knelt on Tara’s chest. He smashed her face and head with the steel plate. Sixteen times.

Someone yelled at him: “What are you doing?” He said: “She’s got my kid.” He bashed her another 13 times, the triple-0 call recording every unthinkable blow.

Then he ran off, dropping the bloodied steel plate onto the face of the woman he professed to love. The mother of his then three-year-old girl, Aria.

Neither Tara nor Patea have Aria now. Tara died. Her injuries were non-survivable. At 5pm that day, September 8, 2015, her life support was turned off. Her body fought for another 28 hours before she slipped away. Patea is in jail. He’s not due out until 2048.

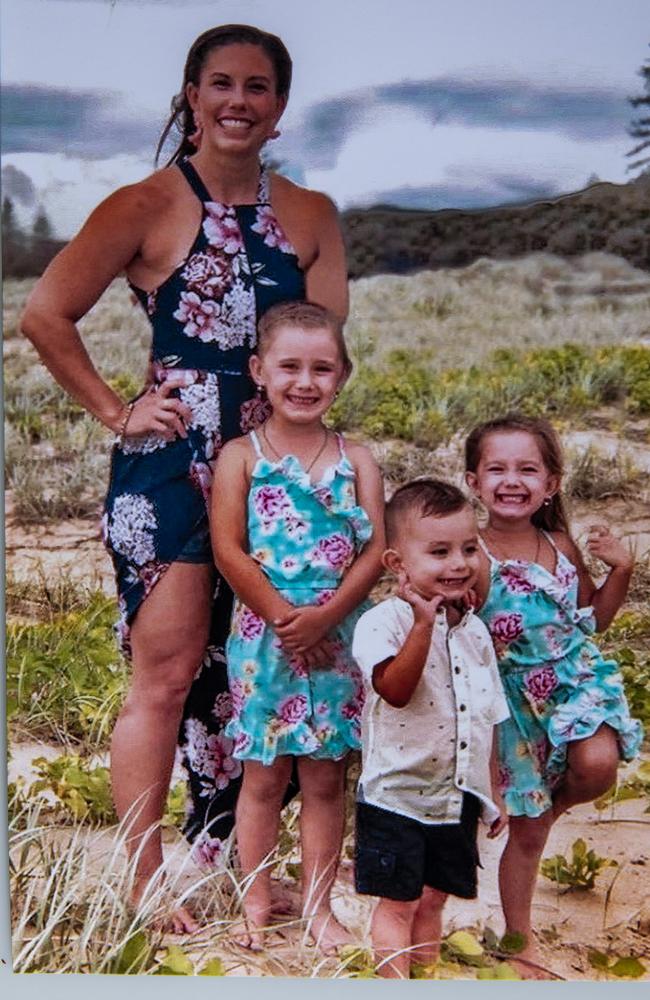

Aria, the little girl that Tara dropped off at daycare just before Patea’s monstrous attack, is cared for by Hinton now. She just turned 10. Her birthday cards are sitting on a side table of their Gold Coast home.

Next to a photograph of Tara.

‘I JUST WANT TO HELP SAVE A LIFE’

Early on the morning after Tara died, a grief-stricken Hinton drove past the Helensvale McDonald’s as police cars flew into the fast-food joint, lights flashing. Karina Lock, a mother of four, had just been shot dead by her estranged husband Stephen.

It never stops.

“There was Fabiana (Palhares), Hannah (Clarke).” Hinton says. “I know all their names. It affects me deeply each time. It makes me think of what those families and friends are going through, the ripple effect.”

Hinton’s life was permanently rerouted by Tara’s violent death.

Dreams of spoiling Aria in the way grandmothers do vanished. She would need to be a mother to a confused little girl who had been robbed of hers. “I just want her to have a normal life,” says Hinton. “A normal, happy life. Let her be a kid.”

But there was so much else for Hinton to do: police interviews for Patea’s court appearances and lawyer meetings to negotiate Patea’s family’s demand for access to Aria.

Hinton went to vigils, gave speeches, met with politicians, and created the Tara Brown Foundation to raise money for refuges and domestic violence support.

After a few years, when life with Aria settled into the rhythm of school, music practice and sport, Hinton wanted to do more. “I just wanted to help save a life,” she says.

She started volunteering at Gold Coast refuge, The Sanctuary, about three years ago. Last year, she took on a job as a case manager.

Her final assignment for a community services diploma sits on her dining room table.

But no amount of study can rival Hinton’s real-life experience of domestic violence. She was a victim herself when Tara was about 18; belittled, spat at, stalked to the point of police intervention after a brief relationship.

She knows the signs.

She saw the early wooing by Patea of her daughter, then his growing control, his jealousy, the incremental erosion of Tara’s sense of self and safety.

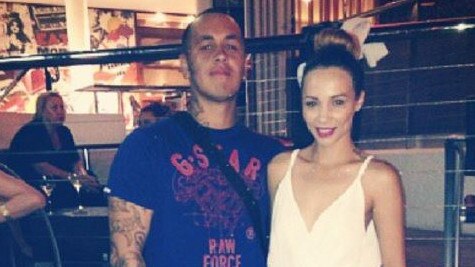

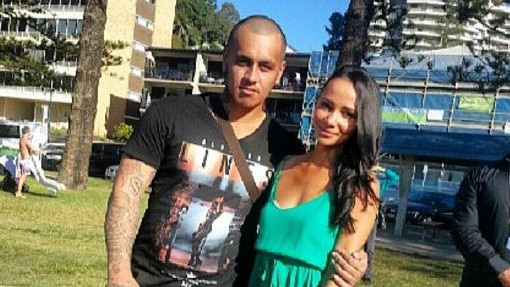

Tara and Patea had known each other since they were about five, both members of the Gold Coast’s New Zealand/Maori community.

His aunt was a neighbour when Hinton and her long-term partner, Patrick Brown, emigrated from New Zealand in 1995 with children, Tara and son Rikki, now 29.

“They’d have kids’ birthday parties, the cousins would come and we were invited; they knew each other but they were never childhood sweethearts,” she says.

Over the years, Hinton’s kids would come home with stories about Patea and his brother, Nelson, “always getting in trouble”. By then, Hinton was raising her kids alone. Patrick died suddenly when Tara was 11.

“It was quite a hard time; kids coming into teenage years, a brand new mortgage, but we made it through,” says Hinton.

Tara was a keen touch football player, making the Queensland under-15s rep team and continuing to play into her adulthood. At 17, she got a job as a receptionist at a law firm, had a great group of mates and was forging ahead.

Then, Tara came home with Patea. Hinton rues the day. She remembers pulling Tara aside. “What’s he doing here?” she asked the then 20-year-old. Tara said they were just friends. “Well, you could pick better friends,” Hinton said.

Hinton trawled through Patea’s Facebook posts and didn’t like what she saw. “He was obviously associating with outlaw motorcycle gangs,” she says. “There were pictures of him with his tattooed friends.”

Hinton denies Tara was enamoured by gang culture.

“But I could see he was buying her,” she says of the ensuing months.

“He was showering her with gifts, showing the money. We’d struggled all the way through; I couldn’t shower her with all the gifts like he was. I could see that was catching her interest, making her feel good. Making her feel special.”

Three months after bringing Patea home, Tara was pregnant.

“My heart hit the ground,” says Hinton.

Soon after, they moved in together and Patea became a “prospect” with the Bandidos.

“And from that point on, it just all went to shit. Things just went downhill.”

The fighting began. Patea restricted time with friends, monitored her whereabouts.

Tara always had to dress to his liking and wear make-up.

He accessed her bank accounts.

More than once, he smashed up Tara’s car during unhinged rages over trivial things.

“I’d see bruising on her arms, like he’d been forcefully holding her,” Hinton says.

“There were no black eyes or broken bones. It was more coercive control; mental, emotional abuse.”

Patea was dealing drugs for the Bandidos, gaining a reputation as a violent enforcer.

Tara told Hinton of the “copious amounts of money” Patea handled; that she had seen guns.

In fact, the coroner reported he’d threatened Tara with a handgun in this period.

Bit by bit, Tara’s demeanour changed; she was not the same vibrant woman, becoming nervy and snapping at her mum, who she spoke with on the phone every day.

Hinton told Tara to leave.

Tara wouldn’t.

“She still believed she could have a happy, loving family. Or she had that hope. I don’t think she believed it. She had that hope.”

Patea’s violence hit a new low when Tara was 33 weeks pregnant.

It was April 2012 and they were in her car near Mermaid Beach.

They argued. She asked him to stop speaking to her so rudely.

A few horrific minutes later, Tara called Hinton. “Mum,” Tara sobbed, “he’s smashed my car again; he’s ripped my dress off.”

Hinton shakes her head as she recalls that moment. “She’s seven months pregnant!”

Hinton rushed to her daughter.

The distraught Tara had found a sarong in the car and wrapped it around her.

The windscreen was smashed, the side mirrors kicked off, the keys thrown away.

Patea had spat in Tara’s face and called her a “putrid dog mongrel slut”.

Then he slinked off.

The Broadbeach police station was nearby.

“I waltzed her in,” says Hinton, “and I said, ‘I’m not leaving until you lay charges or you’ve got a domestic violence order against him’.”

Tara was too afraid to press assault charges but police applied for a domestic violence order. It wasn’t served on Patea until June 15, almost two months later.

Hinton took Tara back to her place and she stayed about a month.

Then Tara decided to go back; she wanted to be in her own home when the baby arrived. Hinton said: “He’s not allowed to be there.”

Tara agreed, but Hinton says she knew Patea would wangle his way back into her life.

“Of course he was going to be there,” Hinton says.

“She was saying I can raise the baby alone but I knew even if she ended the relationship, he would always be around. She was his possession. She was having his baby. That was his second possession arriving.”

On May 20, 2012, Hinton got a call from Tara saying she was heading to the hospital for the birth. Hinton said she’d drive her. Tara said that wasn’t necessary. Patea was taking her.

ARIA’S ARRIVAL

Tara gave birth to Aria the same day Patea threatened to slit her mother’s throat.

It caused mayhem, of course. That was the way with Patea. Things could explode in an instant.

Hinton recalls walking into Tara’s hospital room about 1pm, all eyes on her daughter. “There’s my daughter having my first grandchild,” she says. “I was really excited for her, just focused on Tara.”

Patea was on the other side of the bed. Hinton says she didn’t hear Patea say hello. He thought she’d ignored him. He left.

“The next minute, he’s ringing Tara, abusing her because, ‘Your f--king slut of a mother didn’t say hello to me’,” says Hinton.

“She’s in labour! She’s screaming and upset.”

And then he said: “I’m coming back to slit your mother’s throat.”

The midwife overheard the threat.

Security greeted Patea on return to the ward.

Family counsellors and hospital staff flocked in.

Hinton told them to call the police. They didn’t, instead deciding Patea and Hinton would alternate being with Tara every hour, with Patea, guarded by security, there for the birth.

Aria was born at 10.20 that night.

Hinton beams at the memory of walking in to see her granddaughter.

“Oh, it was beautiful, it really was. I’ve got a really nice photo of Aria soon after she was born with Tara looking up at me like, ‘I did it, Mum’. She looked happy. She looked like a new mum.”

The happiness didn’t last long.

By late June, the abuse boiled over and Patea took Aria from Tara after an ugly confrontation. When the baby was returned by Patea’s mother, Hinton spirited Tara and Aria away to the home of Jonny Gardner, Hinton’s new partner whose address Patea didn’t know.

Patea bombarded Tara with texts, like this one on 12 July 2012: “if u dnt pickup Im guna smash d fuk owta our house n kill zuez [their dog] at least I knw were to go to get ur mum I warned u wat wuld happen”. It was just one of 12 texts and 30 calls within two hours.

Soon after, Tara got a chilling text from Patea; he knew her address. Hinton took her to Coomera police station. Hinton recalls looking after Aria as Tara gave a statement, and seeing Patea’s face on a wanted poster. “I’m in total disbelief. ‘Oh my god, Tara, you must leave him’. And Tara said: “Oh Mum, Mum, it’s not that easy.”

Tara knew: she was the girlfriend of a bikie, the mother of his child. She was trapped.

Patea was arrested and had a short stint in jail for other offences. (He was arrested for breaching Tara’s domestic violence orders twice, receiving a one-month sentence, wholly suspended. He also breached an order relating to a former girlfriend, which led to a jail period.)

And then, he was back. A pattern took hold: Patea would turn up, Tara would relent and let him see Aria, and soon the violence and control would reignite.

“I moved her in and out, in and out, in and out,” says Hinton.

“Eight times.” That’s about the average number of aborted escapes, says Hinton, before abused women make the final break.

Hinton is convinced a major reason Tara continued to let Patea back into her life was her fear not just for her own life, but the lives of Hinton and Rikki.

“She told me he made threats to hurt us,” she says. “She took it very seriously.”

Tara tried to mask her fear, especially around Aria.

“She was a great mum. Aria was her pride and joy,” Hinton says.

“She loved taking her to the beach, singing and doing fun things with her. Lots of photos; lots and lots and thousands and thousands of photos.

It was hard for her to go back to work and put Aria into daycare but she did it.

She knew she had to provide for Aria, become independent, that was her sole focus.”

Tara returned to work at a new law firm, JHL Lawyers at Southport, as a personal assistant in mid-2013.

Changes were in the wind for Patea, too.

In September 2013, frightening footage of a massive bikie brawl at the Aura restaurant in Broadbeach filled the news.

Arrests were made and Patea was one of a posse of bikies that gathered outside the Southport police station, hollering for their members to be released.

He was arrested.

Hinton says Tara hoped it would mean a jail stint, giving her a break from his control. He received a $2500 fine.

The brawl ushered in the controversial anti-bikie laws of the Newman government and Patea made a decision.

By November, he’d surrendered his Bandido jacket and paraphernalia. By 2014, he was working in Queensland mines as a FIFO worker.

These were marginally better days, says Hinton, but there were still fights, separations – and control.

“Him working away gave her a reprieve,” says Hinton.

“But when she was with us or her friends, he was constantly monitoring her through phone calls or texts, ‘Where are you, what are you doing, what are you wearing, what time did you leave, when are you going back, have you got make-up on, how many boys are around?’ Just constant. Shocking, absolutely shocking.”

Jealousy and control underpinned the relationship. Tara was a beautiful woman and Patea jumped at any sign of her taking an interest in other men, of moving on.

It was a repressive, suffocating existence.

TARA TRIES TO BREAK FREE

Patea crept up behind Tara in Auckland’s airport departure lounge as she texted a friend. Suddenly, his hand darted over her shoulder and grabbed for her phone.

“Stop Lionel,” Tara yelled. “And they’re gone!” says Hinton.

“He’s chasing her through the airport.”

A few minutes later, Tara returned: no phone, her braces on her teeth knocked out, security with her. Patea was walked back by security to another lounge.

Patea had her phone. Tara was shaking.

Patea had invited himself on the Hinton family’s New Zealand trip at the last minute and was on a flight back to Brisbane.

Tara, Aria and her family, were flying to the Gold Coast.

Once in the air, an “uptight, fearful” Tara made plans to get her and Aria out of the home she shared with Patea before he got back.

What would Patea find on the phone? Hinton isn’t sure.

But she does know that Tara had “become closer to someone” she met at touch football. Shortly before leaving for NZ, Hinton noticed Tara smiling as she texted.

Hinton asked who it was and Tara had said, “Just a friend”.

But says Hinton: “I could see this was different. I could see her light up.” (The man told police after Tara’s death they had met in May 2015, had recently become intimate and were texting each other while she was in NZ.)

Tara was packed and heading out the driveway when Patea arrived home, raging.

The Coroner found: “Mr Patea dragged her to a room, threw her on the bed, closed the door and put scissors to her neck. He threatened to stab her and cut off her ear. Ms Brown was scared for her life and was crying. Mr Patea refused to let her leave or check on her daughter.”

Tara was locked in her room all night.

He emptied her bank account.

He sent messages to her workmates telling them she was having an affair.

He disseminated photos of her in lingerie.

He had a friend post a video of Tara, on her knees and crying, covering her face with her hands, as she said, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry” while Patea called her a slut.

Then he kicked her out the next day.

He kept Aria, leaving her with one of his aunts while he went back to the mines.

By Wednesday, Tara confided in her boss, Jason Hall, who heard some of Patea’s incessant, abusive calls. In 10 hours, he made more than 270 texts and calls.

Tara had had enough.

She sought refuge in a domestic violence shelter.

She phoned Hinton and asked her to pick up Aria from daycare.

Then Hall took the trio to the Southport police station to get a DVO against Patea.

They hit an unbelievable snag.

A young constable looked at the texts and decided that while Patea was threatening to take Aria, he did not threaten Tara.

Hinton had the impression he was more interested in finding out about Patea’s gang involvement than Tara’s fear.

He provided no DVO, forcing them to go to court to organise a private order. With that in place, Tara and Aria left the Gold Coast.

Meanwhile, Hall organised temporary custody arrangements for Patea to see Aria, on Sunday, Father’s Day, via a third party.

Patea had learned Aria had been taken from daycare and, enraged, was on his way back to the Gold Coast.

Hinton and Gardner, as well as Hall, left the coast to escape Patea’s threats. All weekend, he hounded Tara’s friends and other relatives to reveal her whereabouts.

On the Saturday, Tara called her mum from the refuge.

They decided to meet at the Eumundi markets.

It was a rocky start, with a tiff about Patea having control of Tara’s bank accounts and Hinton’s fears about the Father’s Day plan.

But Tara said she had to take Aria back. She wanted to do what was legally right.

“We calmed down and we had a really, really neat afternoon,” recalls Hinton.

“We went to the beach at Coolum, threw the footy around. We went back to the hotel and she had a swim in the pool and a nice long shower while I looked after Aria. She had to go back to the refuge for curfew. I said goodbye. And that was the last time I saw her.”

ARIA AND NAN

Sometimes, when Aria is running up and down the touch footy field, Hinton sees Tara.

“Aria smiles the whole time she’s on the field and Tara used to do that,” she says.

“Didn’t matter if they were winning or losing by heaps, she’d still be smiling. Aria’s the same. Smiling. It’s uncanny.”

They’re a tight family unit, with Hinton’s mother Jill now living with them, and Aria regularly seeing Rikki’s kids and the children of Tara’s friends. Aria’s musical, playing trumpet and violin, and the driving force behind the woman she calls Nan.

“She’s the only thing that’s kept me going, really,” says Hinton, proudly relaying that Aria has just made a Gold Coast touch football representative team.

“I don’t think I’d be here if not for Aria.”

It’s been a hard road. Around the time Aria started school, she was a lost, sad girl. “She used to get frustrated that, ‘I don’t remember what she looks like, I can’t remember how she smelled’. She was very, very sad.”

Hinton is single now, her relationship with Gardner ending amicably for a range of reasons, she says, but the anguish over Tara didn’t help.

Even after Tara’s murder, more horror about Patea was revealed: he’d murdered before.

Two months prior to bludgeoning Tara to death, Patea was one of a gang of six that killed Greg Dufty, 37, over drugs.

Patea struck the first blow.

His involvement surfaced after Tara died – Dufty’s blood was found in her car. Patea got 30 years for that murder because Dufty’s body has not been found, 20 for Tara’s.

Patea’s brother Nelson was involved in Dufty’s killing, too, and got eight years.

It pains Hinton to say it but she believes Tara’s murder was inevitable.

“If it hadn’t happened then, it would have happened another time,” she says.

“Unless she’d moved countries; I don’t think interstate would have been enough. He would have hunted her down.”

The days and weeks leading up to a woman leaving an abusive relationship are the most dangerous.

Tara had a misguided view that, after the Father’s Day visit went OK, things would settle down. Custody arrangements were being organised; lawyers were involved.

But to Patea, that meant he was losing control. He killed Tara two days after Father’s Day.

That’s why Hinton tells the women she works with at the shelter: “Never go back … I tell them they do not change and you cannot change them.”

But some change in dealing with domestic violence has been made.

The coroner found the Southport police did not understand the legislation to combat domestic violence, or the risks of the violence escalating.

There are 39 “lethality factors” that signal a victim’s life is in danger – Tara suffered at least 27. The Queensland police have since established the Domestic, Family Violence and Vulnerable Persons Command.

The Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce, headed by former Court of Appeal president, Margaret McMurdo, completed its report last month, handing down 89 recommendations.

The Queensland government is already committed to one key recommendation: the criminalisation of coercive control, with legislation due to go to parliament next year.

Hinton fully supports that, and wants more funding for shelters and social workers.

She’s been struck by how much work is done by groups unfunded by government. The demand is huge.

“People are more aware of domestic violence now – because of the Taras and the Hannahs.”

Hinton is doing her share to help, working at the shelter and recently appearing in a police film aimed at stopping young women becoming involved with gang members.

It details Tara’s terrifying entanglement with the man who would eventually kill her.

It’s raw and heart-wrenching but fades in comparison with the monumental task ahead of Hinton.

Soon, she will sit with Aria and give the little girl a more complete account of what happened to her mother.

Of what her father did.

Right now, Aria believes her mother died in a car crash.

She knows her father is in jail for hurting people.

Psychologists have told Hinton that Aria is now at the age when it’s time to fill in the gaps, before she learns the ugly truth from friends or the internet.

Hinton pauses as she contemplates that day.

“I don’t know how she’s going to take it,” she says.

“I don’t know how the hell I’m going to get through it. No child should ever have to learn that about their parents. Ever. Yet so many kids have had to.”