Extraordinary story of family of secret agents living in suburban Brisbane

The Dohertys looked like an ordinary family from the ordinary Brisbane suburb of The Gap. But looks are deceiving: they were spies who went on holidays with Soviet defectors, the Petrovs.

QWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from QWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to believe that tucked away in the perfectly ordinary Brisbane suburb of The Gap, lived a family of spies.

Mum, Dad and the three kids. They went on holidays to the Gold Coast with Soviet defectors, the Petrovs.

Dad did the books for Abe Saffron, one of Australia’s most notorious underworld figures.

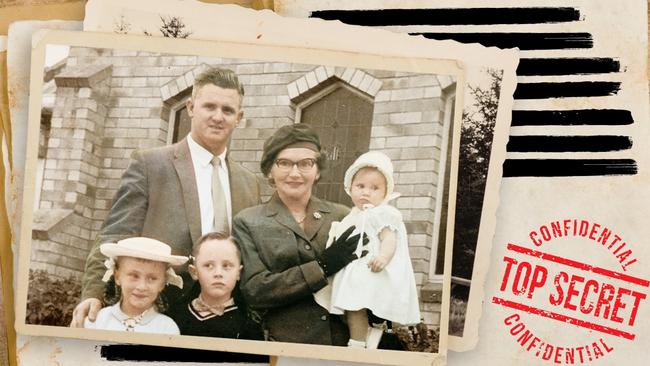

They’d pop into the city looking like an everyday family posing for happy snaps but that was a ruse; they were busy collecting intelligence on could-be Communists.

If it’s a mission too outlandish, too impossible for you, that’s understandable. Even the woman who lived this story finds big chunks of her childhood hard to believe.

Sue-Ellen Kusher is 68 now; a forthright woman who lived with the secret of her upbringing until she could no more.

Until the nagging questions of who she was, and more importantly, who her parents were, became too loud to ignore. “[My siblings and I] didn’t know our own story, only our little bits of it,” says Kusher.

[My brother, Mark Doherty, now 69] knew his little bits, [sister, Amanda Kojovic, 62] knew her little bits. We knew never to ask questions. So we had all these gaps.”

‘The VC cost me my marriage’: Keighran

‘Being told I would die made me live’: Three incredible tales of survival

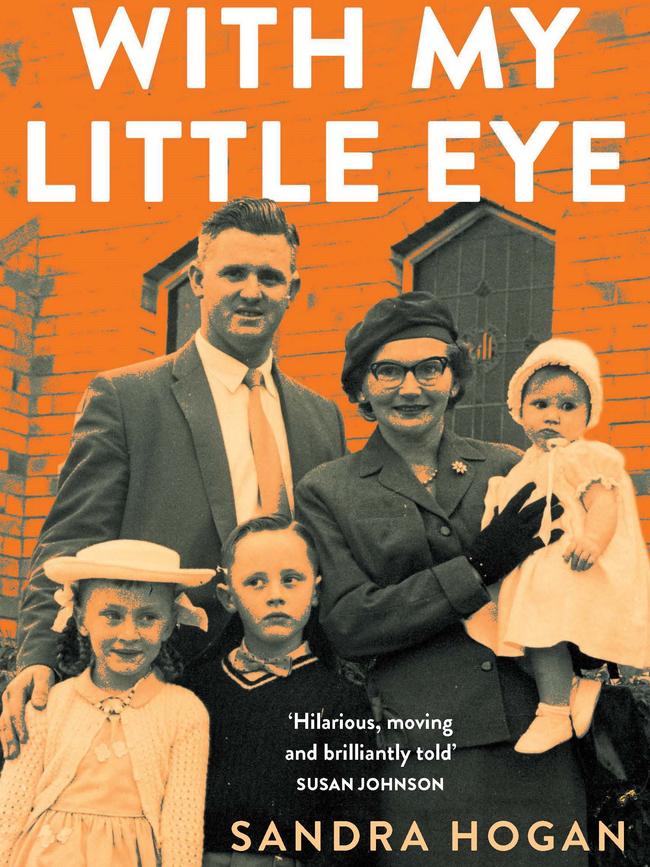

Many of Kusher’s questions are answered in the soon-to-be-released With My Little Eye, a book about the oh-so-normal-seeming Doherty family of The Gap, by journalist Sandra Hogan.

Hogan was sceptical, too, when Kusher asked her to help unravel her family’s story in early 2010.

Even if Kusher was right, reasoned Hogan, and her father, Dudley Doherty, was an agent for the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation for 21 years, everyone knows spies don’t tell their kids. And they certainly don’t enlist them into the spying game.

Turns out they do. And the subterfuge and contradictions of the Doherty parents have had a profound effect on their children.

Until recently, Kusher still half-believed that her father, who had a fatal heart attack when she was 17, was alive and on a mission.

She now accepts he’s dead – and has learned that a daughter’s rose-coloured view of a long-gone father can grow murky the deeper you look.

Unearthing her family’s past was made much easier when ASIO called in 2011.

The then Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, had given permission for the history of ASIO to be written. Researchers from the Australian National University and ASIO directors wanted to interview the family matriarch, Joan Doherty.

They visited, handing Joan, then 82, a letter that said she was no longer bound by an oath of secrecy.

Once that book, The Spy Catchers, was released in 2014, Joan agreed to talk to Hogan. Over 11 visits, the incredible story of the family of spies that lived at The Gap began to unfurl.

Then it was the children’s turn to talk.

Things they’d repressed their whole adult life wiggled free.

There was all that training to remember and report number plates, faces, things that seemed odd.

There was their insinuation into the Chinese and Yugoslav communities of Brisbane in the midst of the Cold War.

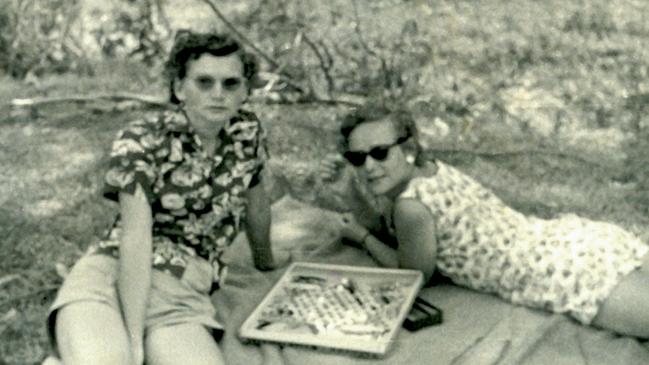

And there was a box of family photographs, little black and white treasures, that held the proof of that summer the Dohertys frolicked on the beach with Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov.

One of Kusher’s favourite missions was to go with her father into the city to the ASIO office in Brisbane’s Queen Street. The secret one, with the secret floor.

The lift operator knew about the unnumbered floor, and would stop the lift for those authorised to go there.

If others were in the lift, he’d deliver them first. Kusher knew him as Mr Buchanan, the man who would swap slippers and sandals with her Dad.

Both were amputees; her father lost his left leg in a traffic accident and Mr Buchanan was missing his right leg.

It was all very Get Smart.

Once allowed through a timber gate by the receptionist, there was a long hallway and a huge steel door to go through. Kusher would sit quietly for hours to wait for her Dad to emerge. “The Cone of Silence,” jokes Kusher, now a mother-of-three and business presentation consultant living in the inner-east suburb of Bulimba.

“We were well and truly in it.”

Dudley Doherty had been with ASIO almost from its inception in March 1949. It was formed after the US and UK expressed deep concern about Australia’s slack approach to the threat of espionage. The two allies had uncovered the Venona files, coded messages being passed between the KGB in Moscow and Soviet spies in embassies around the world. Australia had a Soviet spy ring.

Dudley was suggested as an ASIO recruit by a fellow Mason who worked there. ASIO liked to employ army personnel and Dudley had served in WWII, an enlistment that took multiple applications because of his wooden leg.

He was in supply and it was at an ordinance depot in Moorebank, southwest Sydney, that he met young Corporal Abe Saffron, forming a lifelong friendship.

Joan also joined The Firm, as insiders knew ASIO, soon after marrying Dudley in late 1949. Kusher knew this but it wasn’t until the ASIO book researchers visited that she learned her mother’s vital role.

“They turned up with flowers, chocolates, a letter from Julia Gillard, an official thank you and a document that gave her permission to speak,” recalls Kusher.

“It took Mum a good 20 minutes before she could say anything. They said, ‘We have had exactly the same reaction from everyone’.”

What a story Joan had to tell. Each day, she’d go to Agincourt, ASIO’s HQ on Sydney Harbour, and head behind a green door. Inside were the Australian intercepts of the Venona tapes. Most were in Russian.

Joan did not speak Russian.

But in 12-hour shifts, she would listen out for key phrases or names, and give them, and the time they were mentioned on the tapes, to an interpreter.

Soon after, the Dohertys became part of ASIO’s first bugging operation.

They were moved into an apartment in Sydney’s Darlinghurst – above the home of suspected Russian spy, Fedor Nosov, of the Soviet news agency TASS.

Holes were bored into the ceiling of Nosov’s flat but it was a sloppy job. Plaster dropped onto Nosov’s floor. An ASIO officer had to clean it up.

That officer was Ray Whitrod, later to be Queensland’s police commissioner.

Joan listened to Nosov’s conversations and transcribed them, until Kusher was born in early 1953 and the now mother-of-two resigned from ASIO.

“I didn’t know that story,” says Kusher. “I didn’t know any of those stories.”

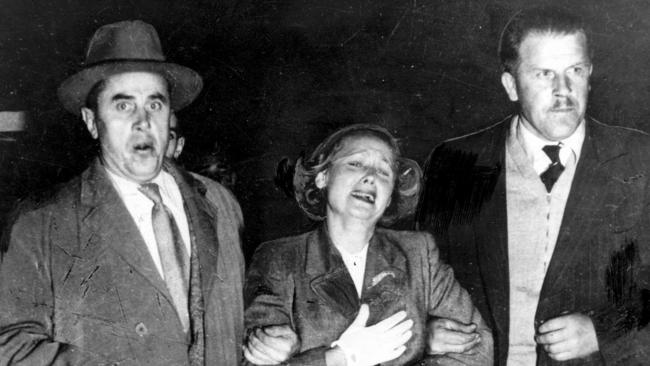

What Kusher did come to know as she grew up was that the caring, well-groomed Russian who painted Kusher’s toenails during a beach holiday when she was three was Evdokia Petrov.

It was 1956, the year of the Melbourne Olympics, just two years after the Petrovs had defected, one of the most sensational events in Australian history.

The former third secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Canberra and his code clerk wife were now living in Melbourne.

Vladimir had turned over documents to ASIO that led to the unveiling of 600 Russian spies. Fears grew that the KGB would send operatives to Melbourne under the guise of Olympic officials to assassinate the Petrovs. They had to get out of Victoria.

The couple was initially placed with an ASIO family in NSW but Evdokia was incensed by the way the wife peeled vegetables without first washing them.

So they ended up with the Doherty family, which had just been transferred to Brisbane by ASIO. With two cars – enough to fit other ASIO agents in – the Dohertys and their then two kids set off on holiday to Surfers Paradise with the Petrovs.

“I only remember his feet, they always looked dirty to me,” says Kusher of Vladimir Petrov.

“He terrified me.”

She loved Evdokia, though, who, for a reason lost in history, they called Peewee. “She was lovely. We used to go to the beach a lot.

She’d paint my toenails, I mean, with nail polish. Oh my God! It was just the best.”

The detail in the book of that long summer is courtesy of Joan, who became very friendly with Evdokia.

She told Hogan that Evdokia and Vladimir were not close – perhaps understandable given he defected without telling her, leaving her to be locked in a room in the Soviet embassy before being ushered onto a flight to Darwin en route to Russia and what many believed would be torture and death.

ASIO intervened at Darwin and she defected.

Evdokia felt trapped; unable to return to Russia and living with an egotistical drunk who would often sit in his lounge without his pants on.

That disgusted Evdokia and if he didn’t put his pants on, writes Hogan, “she would bite his penis, to annoy him”.

Joan would never allow the kids to go upstairs where the Petrovs stayed in the Surfers Paradise flat they shared.

One night, Vladimir went to the pub.

He got rolling drunk and knocked on a neighbour’s door.

Not a good move for a Russian defector meant to be incognito.

Joan’s recollection is that the neighbour redirected Vladimir to his lodgings but recognised him and called a newspaper.

However, in recent years it has been reported that he got into a fight with the neighbour, police were called, he admitted to being Vladimir Petrov and was taken to the Southport police station, spending the night in a cell.

Either way, his cover was blown.

Suddenly, Dudley was telling everyone to pack up and get in the car.

“I can remember being chased at the Gold Coast by another carload of people,” says Kusher.

They may have been media or KGB.

“I had no idea who they were. I thought it was fantastic. I could feel the energy was up. We were speeding along; I can even remember Dad turned right off the main road and wound his way up a hill. [Dad said] ‘We’re just having an adventure’.

Then he drove down, obviously trying to lose them and took off again.”

They ended up in Redcliffe but, within a few days, Dudley was told the KGB was onto them. Next stop, Caloundra. Soon after, the Petrovs returned to Melbourne.

“We were then exited,” recalls Kusher, “and Mum said Dad got into a lot of trouble because he let the media get to him.”

It was the last time Joan saw Peewee.

When Kusher, years later, suggested she try to find her, her mother smiled. “I know where she is,” she said. But contact was forbidden.

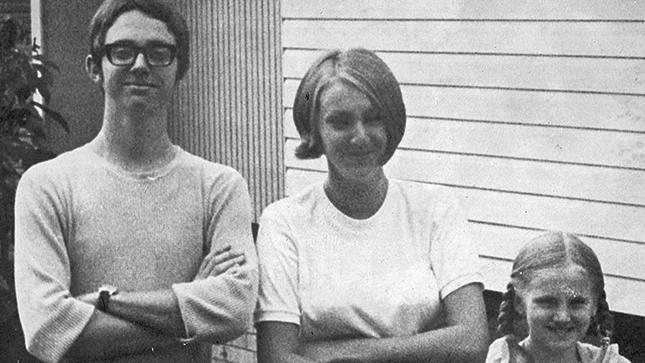

The Doherty’s moved into a brand-new double-brick home at Kilmaine Street, The Gap, on November 22, 1963 – the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Mark was 12, Kusher 10 and Amanda five. Old enough to help The Firm flush out Communists.

This was ASIO’s Reds Under the Beds period, a post-McCarthyist trial-era obsession with Communist infiltration of Australian organisations.

The threat was real but ASIO was a conservative organisation and Left-leaning groups of all guises were swept up in its anti-Communist fervour.

Vietnam War protesters, Aboriginal land rights activists and social advocacy groups were all in its sights.

Dudley was a true believer in the ASIO cause and hung out with other spooks, federal and state police, and customs officers.

He dressed for anonymity; suit, mute tie, white shirt. He went to May Day marches, Speaker’s Corner and protests with the kids, taking pictures with them in the foreground but with his focus on the unionists and activists behind.

Sometimes, Dudley would say, “We’re going out in the car” and the trio of kids would grab a change of clothes and head to their nondescript Holden.

He’d drive past places such as Brisbane’s union HQ, Trades Hall, with all three kids in the front. Then he’d do laps, after the children changed clothes and seats. One might hide on the floor.

It was never explained why. And questions weren’t allowed.

“It’s Dad’s job,” was the standard response. Kusher saw the accoutrements of his work – a wax-kit used to take impressions of keys and a lock-picking tool – but never asked about them. Snippets slipped out, though.

One night, Kusher found out he was trapped inside the premises of someone he was spying on. He didn’t get home until morning.

The children knew he worked for ASIO but were instructed to tell no-one. If asked, they said he worked for the public service. If pressed, the Attorney-General’s department.

Dudley’s primary role was to “know every Chinese person in Queensland”, says Kusher, who would sometimes go on his surveillance trips north.

Later, focus shifted to the Yugoslav community. Dudley could turn on the charm and the family became friendly with many of those he had under surveillance.

Kusher still believes he did things to help them because of his generosity, not his job. The kids loved their exotic friends, too, but their presence at the gatherings doubled as great cover.

If the kids said anything that might raise suspicions, they’d get a swift non-verbal cue to shut up.

“They were micro-movements from my parents that told us to get yourself under control and think about what you’re doing,” says Kusher.

“It was bred into us; it was a gradual thing. And it was constant.”

It’s hard to fathom but Kusher says she never told anyone about her father’s work.

She never even talked about it with Mark or Amanda. Not even something like, “Hey, how about Dad’s cool wax kit?”.

“Not ever,” says Kusher, “because that was the secret and … a secret was between you and me, and once you had given it to me, I locked it away.”

Kusher believes her husband, Hugh, best summarised how the children were so controlled. “He said, ‘You were brainwashed from the day you were born’.” Says Kusher: “That’s a harsh term but that’s what it was. Part of the secret was that you never asked about the secret.”

She adds: “I think we thought we were a little bit special because … we thought we were helping Dad keep Australia safe.”

Kusher idolised him, despite his almost daily “beltings” of her, the boisterous child. She rarely knew what she’d done wrong and admits it left her bewildered.

As she grew older, her questions grew.

Who was her father?

She figures she had about three real conversations with him before he died.

“I had no idea what his ethics were; no idea how he value-moderated what he was doing.”

Hogan says she’s watched Kusher become “more doubtful” about her Dad as more details came to light in their research. Kusher did know as a teenager that he was having an affair. Joan, who remarried after Dudley’s death but still regards him as the love of her life, told Hogan there was more than one woman.

Dudley wasn’t averse to making the most of the access his job afforded, either. Kusher remembers going to Brisbane’s port with him and coming home with whole salmon or stacking the corner of a room with boxes of Mars bars and chewing gum.

“By today’s standards, he would have been a child beater; he would have been up on graft and corruption,” she says.

Then there’s the Abe Saffron connection.

Dubbed “Mr Sin”, Saffron was one of the best-known crooks in Australia, owning a host of nightclubs and strip-joints in Kings Cross and running rackets in sly grog, gambling, prostitution and drugs. He was suspected of being involved in the 1975 murder of anti-development crusader and heiress Juanita Nielsen. It was said – and in parts, confirmed – that Saffron had politicians and police in his pocket.

Despite scrutiny from law enforcement and Royal Commissions, Saffron’s only spell in jail was in 1987 for tax evasion – for having two sets of accounts, the true figures in one set of books and the fabricated ones in another.

Dudley did Saffron’s books. Not in that period, of course – Dudley died in 1970. But every year, Dudley would visit his old army chum and do his accounts. And partake in the “jolliness”.

“I have been told stories [by my mother] about what the showgirls used to be like; the casting couch, the performances,” says Kusher.

Joan maintains Dudley did the “good” books. Kusher has other ideas. “I think he did the bad books,” she says.

“Which then throws all my values about him into question.”

Was he a hypocrite?

She can’t bring herself to go quite that far, but close.

“I think some of the things he did were hypocritical,” she reasons.

“I think he was a larrikin; I think he was charming and he knew it. I think he could get away with stuff. And he did.” She adds: “I think my father was very good at segregating sections of his life.”

Kusher is convinced her father knew Saffron was crooked – but is adamant ASIO had no idea about his mateyness with Mr Sin.

If true, it’s not a great advertisement for a spy organisation. But Kusher’s belief was cemented by the reaction of Dudley’s former Queensland boss, who she called Uncle Mick, when she told him in recent years.

“He nearly had a fit,” she says.

Hogan likes to quote Amanda on the enigma that was Dudley Doherty.

“He was a man who lived in the grey. There’s right and there’s wrong and there’s somewhere in between. And he was there.”

Fade to black. On October 18, 1970, Dudley Doherty, 47, is at home, eating takeaway chicken and cashews. He gets up abruptly and heads down the hall. Within minutes, he’s dead.

Kusher is at a Johnny O’Keefe concert. She arrives home to find people everywhere, the house in turmoil, her world up-ended. Mark has been busily ringing all the agents and police Joan has instructed him to inform. Amanda is at a neighbour’s house.

Next day at 6am, two men in dark suits arrive.

They take Dudley’s lock-picking tool and notebooks, even shake his wooden leg upside down in case something is hidden inside.

They remind Joan to stay mute about ASIO. They ask her to line up the kids so they can talk to them. The feisty Joan tells them she’ll do that herself.

The shock of her husband’s death throws Joan into six months of depression. Kusher leaves her job at the Mutual Acceptance Company to look after her, Amanda and the house. Mark moves out.

By now, almost all their friends, contacts, the Chinese and Yugoslav families they’d come to know, had faded from their lives, much of the distancing at Joan’s insistence.

After Dudley died, she was summoned to an ASIO meeting in Sydney, telling the family she was instructed to sever ties.

When she emerged from the fog of grief, Joan was different. Completely. The buttoned-up, rule-abiding Joan was gone.

She sold the house and moved the girls to an apartment in inner-city Red Hill. She started drinking and having casual sex. “She was crazy,” recalls Kusher.

“Dressing like a teenager, smoking joints. Every jar you’d pick up in the house, there’d be a joint.”

It’s almost unimaginable but when Sue-Ellen was 19, her mother organised for her to lose her virginity.

She didn’t tell Sue-Ellen but schooled up the boy. She lit a fire and arranged a bed of pillows on the floor, put out some wine, and Jatz and cheese, and left them to it.

Kusher never discussed this bizarre ceremony with Joan. “Just quiet seething,” she says.

She now reasons that her mother’s own childhood trauma had resurfaced after the loss of Dudley, the man she saw as her rescuer from her family home. Joan had been sexually abused by her father.

But Kusher still finds it hard to forgive.

“It’s the betrayal,” she says.

“She betrayed the rules, she betrayed Dad in a way because of her behaviour afterwards.” She pauses. “Then I think, ‘Well it’s no worse than he was’.”

Dudley had been dead 41 years when the siblings met on Kusher’s veranda with Hogan.

They were going to talk.

About their childhood. They’d never done that before.

“All of us had some system in our head for putting the secrets where they needed to be,” says Kusher. “And just not go there.”

Mark and Amanda insisted they could not remember much. They were only there because it meant so much to Kusher.

Then a few snippets trickled out. Then some more.

The trickle became a stream. They laughed and cried, as Mark remembered one snippet, a sister another. “It was so therapeutic.

Sandra was in tears, we were in tears; it was exhausting,” says Kusher. With Hogan as their guide, they began piecing together the jigsaw of their lives.

Kusher no longer looks for her Dad in a crowd, keeping an eye out for a man with an uneven gait and a distinctive crisscross of wrinkles at the nape of his neck.

He’s gone, a deeply flawed man who loved his family and his country but was engulfed in the grey. Joan is 92, in a nursing home with dementia, her odd and contradictory life slipping away.

There are still bits missing in the puzzle that was the family of spies that lived in The Gap. Bits that will never be found; hidden in ASIO files, or lost with the memories of Dudley and Joan Doherty. But Kusher’s mission is complete. The secret is out.

With My Little Eye by Sandra Hogan, Allen & Unwin, $30