‘The VC cost me my marriage’: Keighran

When Daniel Keighran was awarded the VC he had no idea what lengths the army would go to wipe his history and how his life - and his marriage - would spiral out of control.

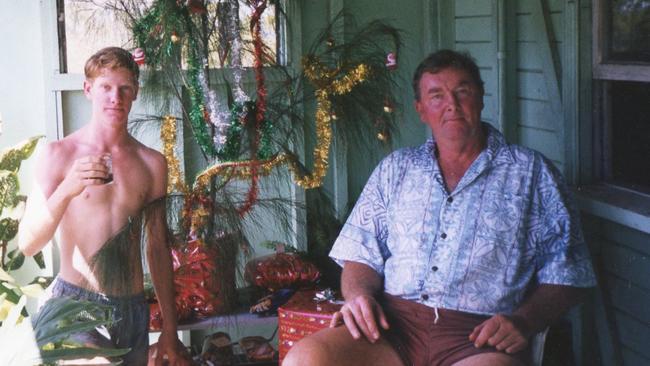

If he hadn’t escaped to the army, chances are Daniel Keighran – Victoria Cross recipient, shoulder-rubber with the powerful, meeter of the Queen – would be a dope grower. He’d be on a bush property in central Queensland, tending cannabis sativa plants, just as he did as a boy under the rough and loveless tutelage of his father. The man he called Cowboy.

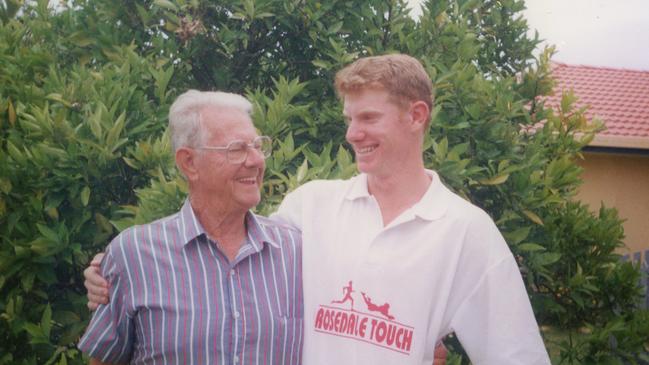

But there was another man in young Keighran’s life, the man he called Grandad. A solid, loyal man who’d fought in World War II but spoke nothing about that when he’d take his grandson fishing. Those days were for yabby pumps and bream, for glorious silence and gentle instruction. A time for Alan Pyburne to repeat his guiding words: “You need to find out who you are as a person, Danny, what you represent, what you stand for.”

There’s a picture on the wall of Keighran’s home in Chermside, on Brisbane’s north, and it’s not of Cowboy. It’s Pyburne, his maternal grandfather who lived in Maroochydore, with the 17-year-old Keighran just before the rangy redhead joined up.

WARNING: ‘I have lung cancer, but I’ve never smoked’

‘Stop being busy, talk to your kids’: Dolly’s family warn parents

“My grandfather took up the role of father figure but he was so much more than that,” says Keighran, 37. “I miss him, miss his guidance.” Pyburne died in 2007.

His father, Ian Keighran, is also dead, succumbing to bowel cancer early this year. Father and son never reconciled. “You know what, it doesn’t even worry me,” Keighran says. “That might sound harsh but his character portrayed in the book is pretty spot on, if anything, I pulled back from really letting loose.”

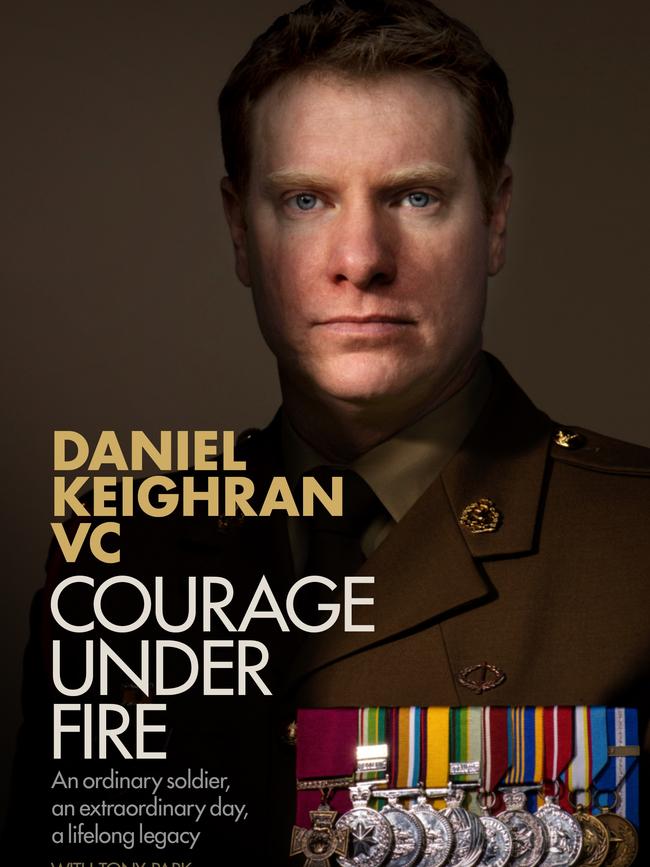

“The book” is Keighran’s autobiography, co-written with Australian best-selling author Tony Park, a story that strips away the airbrushed version of the former soldier’s life curated by Defence when Keighran received his VC.

From the first page – when Cowboy turns up, fresh from hospital, with a gunshot wound to his gut after what Keighran suspects was a drug deal dispute – you know you’re in for a rollicking ride. There are rampaging bulls and bullshit, dead bullocks dripping blood in the shower and the young Keighran’s explosive attempt at making moonshine. There’s the time he got home from high school to get a lesson from a neighbour in how to roll the “perfect” six-paper spliff. There’s the endless work on the property; fencing, mucking out stables, watering the dope crop.

Then there’s the army. How luxurious the spartan quarters at Kapooka, NSW, seemed compared with home; the way a swearing bombardier failed to intimidate a kid inured to the word f..k. The sense of mateship and purpose Keighran began to feel; his time in East Timor, Malaysia, Iraq and Afghanistan.

And there’s that day in 2010 when, with the Taliban’s bullets peppering around him, Keighran crested a hill, and as the VC citation says, conducted “deliberate acts of exceptional courage in circumstances of great peril”. Keighran tells of the complicated nature of being a VC recipient, the honour and the curse. About how he doubted his worthiness, and how the award contributed to the end of his marriage to Kathryn, mother of his son Jack, 3. But it also opened doors, giving him opportunities he’d never imagined.

What the book doesn’t tell, because it’s a chapter still being written, is that Keighran is closer to answering those questions his grandfather posed. The fog of war has lifted and Daniel Keighran is seeing his path – and himself – clearer than ever.

Dust flies in the air as a spooked bull hurtles through the paddock, its horns lowered, its mark set. It’s headed for Keighran’s mum, Judy. And riding straight at the bull is 15-year-old Keighran.

Judy, a normally confident horsewoman, is frozen in the saddle as the bull zeros in. Keighran acts on instinct. He drives his heels into his horse, hollering as he rides, kamikaze-like, at the bull. He’ll either scare it off or be T-boned by a “black-haired freight train”. At the last second, the bull veers away.

“I hadn’t even considered the danger to myself,” he writes in the book, Courage Under Fire. “Somehow my mind and body had known what to do in that moment, without letting the fear of harm paralyse me.” It won’t be the last time he rushes at danger to help.

One thing about his upbringing: it made him tough. Resilient, he says. And stubborn. Or, at times, a daredevil idiot.

There’s a steeliness about Keighran, forged as a boy. He didn’t know his father for his first 11 years, with Cowboy taking off just days after he was born. But Keighran says he never gave him a second thought. He had Pyburne.

When the gut-shot Cowboy returns just as the hardworking Judy has bought a house in Maleny, he recalls watching him from afar, a curiosity, “like an old horse my mum had taken in to take care of”.

Then Cowboy woos his mother again, whisking the family away. To a 16ha block in Lowmead, about 80km northwest of Bundaberg, where Cowboy plans to raise cows, horses and a dope crop.

There is no house. Just a lean-to made of roughly hewn gum, corrugated iron from the tip and plastic tarps. No electricity or running water. They sleep on a dirt floor until, in one cringingly comical scene, Cowboy arrives with a roll of stained carpet and unravels it on the dirt. When Judy mentions the rocks underneath, Cowboy grabs a hammer and smashes the carpet, bedding down the rock, before handing Keighran the hammer to finish the job.

Keighran’s sister Susan is six years older and doesn’t last long at Lowmead. But he has nowhere to go and promptly becomes Cowboy’s workhorse. “He truly saw me as just free labour on the farm.”

And so it went. A solitary boy, working on the farm early in the morning before school, then back for more hard yakka. Oddball mates of Cowboy’s would come and go as life veered from mayhem to uneasy lull. Judy worked hard at keeping the peace. When Cowboy was late home from the pub, she’d head off with her dogs around closing time until he was home and asleep. Keighran, a strong cross-country runner, often took off into the bush with his rifle, hunt, then sleep under the stars.

About 16, he weighed up his options. Grow dope, continue school, or join the army. When a recruiting sergeant tells him army life will challenge him more than ever before, he thinks: “You have no bloody idea what my life has been like, mate.”

As soon as he finishes school he joins the infantry, attracted by its outdoor nature and mission of seeking out the enemy, to kill or capture. He ends up in Enoggera-based Delta Company, 6th Battalion, surprised that such a pivotal moment is done in the same way as picking sides for a school football team.

He writes evocatively of his years in the army, a wide-eyed teenager growing into “a good soldier, not a great one”. He details the high-octane swearing in training, and the realisation on joining the battalion that not all orders are followed and some soldiers are slackers. He goes on his first overseas posting to Malaysia, dazzled by the pretty girls and commingled smells of open sewage, incense and spicy food. There’s a booze-fuelled nude run and a Christmas party held in a Thai brothel.

And there’s mateship, the glue Defence relies upon. But as Keighran discovers at a nightclub in Seymour, Victoria, it can get a soldier into sticky situations.

It’s late 2005 and Keighran is at Puckapunyal learning to drive the massive armoured Bushmaster, hoping it will fast-track him to the Middle East. (It does; he’s sent to Iraq in May 2006.) Keighran heads out for a night in Seymour with other trainees, including fellow Delta Company soldier, Jared “Crash” MacKinney.

Some locals aren’t keen to see the soldiers at the nightclub. A fight breaks out. MacKinney ends up in a chokehold. “I wasn’t going to stand for that, or miss out on the action,” writes Keighran. He elbows MacKinney’s attacker. Then realises it’s a female bouncer.

Keighran and MacKinney are hauled to the police station, later charged with assault. Now as Keighran sits in his loungeroom, a smile drifts across his face as he recollects the forging of a friendship. “We became close when we shared a cell together in Seymour on that wayward night.”

Five years later, he and MacKinney will be fighting together again, under sustained Taliban attack in the Battle of Derapet, in Uruzgan Province, southern Afghanistan.

The chaos of battle is raging all around; bullets flying, muzzles flashing, orders barked. A yell of pain cuts through the cacophony. Corporal Keighran ducks down from his hard-won place on a hill and looks to his left. MacKinney has been shot. A radio call says he’s shot in the arm.

Hours earlier, as Australian forces gathered by a river before their advance, the two mates, stationed at different bases, chatted briefly. Keighran asked MacKinney when his wife, Beckie, was due with their second child. “Not long now, mate,” MacKinney replied. He was hoping to get home to Brisbane for the birth.

Now soldiers are removing MacKinney’s body armour and beginning CPR. Keighran can’t comprehend why. “It was a disconnect; he’d been shot in the arm,” says Keighran. “Seconds later, I saw bullets coming in and I’m thinking, ‘Holy shit, this whole team is about to get killed’.”

The operation had gone through days of planning. The Australians had recently taken over from the French at the Anar Juy base, as the French and Dutch withdrew from Afghanistan. Keighran, on his second tour of Afghanistan, was there to mentor the Afghan National Army in preparation for handover.

The French patrols had not passed a certain point in the Tangi Valley – the point where the Taliban were active. But the Afghan army wanted to regain the valley. The Australian Army agreed. The leader of the patrol told his troops: “We are going to take the fight to the enemy.”

What none of them knew before the three-hour battle, Keighran reveals, is there was a mole in the Afghan Army, relaying their plans to the Taliban. “That’s why they were prepared and ready for us.”

Now, the fight is on. Taliban outnumber them and are everywhere. Keighran’s been shot at before – and was excited by it – but the volume and multiple directions of assault is something he’s never encountered.

Keighran has one slim advantage – he’s on the crest of a vantage point. He knows three things. One, fire must be diverted from MacKinney’s team to allow a helicopter to evacuate MacKinney and, two, it was imperative to pinpoint where the shooting was coming from to target the enemy.

And three, the fastest way to attract fire is become a target. Keighran smiles as he recalls the reaction of the machine-gunner when he told him what he planned to do. “The look on his face!” he says, laughing.

Next second, Keighran is scaling the hill and running, a hulking mobile bullseye. Bullets strike near his feet and fly past his head, from PKM light machine guns and AK-47s throughout the valley. He races along the ridge line, pointing out enemy, then rushes back. It’s not enough. Spotters still don’t have a fix on the Taliban’s multiple positions and MacKinney’s team is still being bombarded. Keighran goes again. “I was drawing fire, it switched from the team and my mate, Jared, lying on his back, to me. I was getting results, so I kept doing it.”

A third 100m dash. This time, he’s certain he’ll be hit. “I honestly should have been killed for what I did,” he says. “Ask any of the guys and it’s like, ‘Yeah, saw Keighran doing that, yep, thought he was going to get shot’.”

Targets are identified now but MacKinney needs to be evacuated. Keighran launches his fourth exposed run, this time off the hill, attracting fire away from MacKinney to clear a landing zone. Then he heads to MacKinney whose team never stopped CPR. He is ghostly pale.

Jared MacKinney died that day, August 24, 2010. “The bullet took him straight in the arm, then straight through his heart,” Keighran says. “We found out later it killed him instantly.”

The Australians pull out soon after. Keighran and his fellow soldiers wanted to return within days. To strike while the Taliban, which lost about 30 men, was depleted and open up the valley. To achieve what MacKinney had died attempting. Headquarters said no. It still rankles Keighran that they didn’t “finish the job”.

“We’d lost two guys a week before with an IED,” he says. “I’m speculating, but I don’t think I’m wrong, someone, somewhere said, ‘Holy shit, this is not the image we want to portray back in Australia’ and absolutely, the handbrake was pulled on.”

He holds similar feelings about Australia’s withdrawal from the Afghanistan war: the job wasn’t done. “I saw the change happening; the infrastructure projects, the kids going to school,” he says. “People had sacrificed so much to give the Afghan people a better life but we did it half-arsed. We lost lives, resources, then we didn’t follow through. I’m no longer in the military, not toeing anyone’s agenda, that’s how I feel.”

He might still be in the military if not for an unyielding Warrant Officer. Back home in late 2010, he requested long-service leave. He was newly engaged to Kathryn, who he’d met in 2007 before his first Afghanistan tour, and in need of shin surgery for ongoing pain that ramped up after his death-defying Derapet dashes. He was due leave. The WO said no.

“He just lacked emotional intelligence; he didn’t realise I’d nearly burned out. I’d been through a fair bit with my mates in Afghan and he just didn’t really care. I was just a number on a sheet of paper for him.”

Keighran put in for discharge and was gone by mid-2011. As for the WO, he’s still in Defence. Keighran smiles. “He’s been promoted.”

Mid-shift, covered in dust and explosives, Keighran takes a phone call in October 2012 at the Kalgoorlie mine in WA where he’d finally found a job. “It’s the Chief of Army,” says Lieutenant-General David Morrison. Within hours, Keighran and his then wife, Kathryn, are at Kalgoorlie airport watching the RAAF VIP jet taxi to the terminal. A handshake, some brief chat, then Morrison hands Keighran a letter in the airport cafeteria.

Keighran has been nominated for the Victoria Cross.

He’s stunned. Four of the men at Derapet had received various honours on Australia Day that year but not him. He was happy for them and reasoned that, despite talk of being nominated, he wasn’t recognised because he’d left the army. The real reason is absurd: the nomination for Australia’s top military honour got lost on a desk. “It was put to the side while there was a changeover of generals,” says Keighran. “Honestly, it was sitting on a desk.”

Keighran wanted to consult his mates but it was clear the choice was now or never. He signed his acceptance. And, as Morrison said it would, Keighran’s life changed. Suddenly, Defence personnel were casing the couple’s modest cottage, and telling him to wipe his social media accounts. They asked about his background. He told them about the wayward Cowboy – but kept mute about his own dope watering duties. Defence whitewashed Cowboy’s life; he would be a rodeo rider, a romantic figure.

Cowboy was at the investiture. “To keep Mum happy,” says Keighran, although his parents had divorced. Cowboy had bolted with a worker who was pregnant with his child the day after Keighran left to join up. Susan was in Canberra, too, proud of her brother. But Alan Pyburne’s absence left a big hole. “I wondered what he might have said to me,” ponders Keighran.

After pinning the VC on his chest, the then governor-general, Quentin Bryce, verbalised his doubts about his worthiness. “You would say you’re no different from your mates … and there were other heroes that day.” But, she said, what Keighran did that day was different and his story would help tell their story.

Still now, Keighran maintains he did not deserve the VC. “I still don’t think I do. Even now, I don’t, no, not at all. I honestly should have been killed for what I did.” What was he thinking when he launched over that hill? “I was thinking, ‘I hope this works’,” he says, laughing.

Keighran’s relaxed manner is at odds with the angst about life after the VC that he describes in the book. The media focus, the formal engagements – including meeting the Queen – lucrative but exhausting speaking tours, and a travel-heavy job with Australian Defence Apparel led him close to burnout. “I’d lost control of my life at that point in time,” he says. His relationship with Kathryn deteriorated and they divorced last year.

He writes that if he had his time over, he’s “leaning towards” saying he would refuse the VC. Asked now, though, and he’s more upbeat. “Twelve months ago, I’d have said absolutely no. I was struggling hard. I’ve come out of that now; things have fallen into place that hadn’t when I was at the end of writing. I’ve finished uni, I’ve got a professional career, I’m in a new relationship. I wouldn’t have had those things without having the VC.”

On a warm spring day, two lovers walk hand-in-hand through Brisbane’s Botanic Gardens, laughing and playing up to the camera. In one deft move, Keighran scoops up Casey Nixon, 28, and holds her in his arms. His smile is huge. They met 20 months ago when he gave a speech about the Bushmaster at Thales Group, which makes the vehicle. She worked for the multinational at Pinkenba, having spent two years in the army. They chatted. He followed her on LinkedIn. In November last year, they met again at a Thales Christmas party; he was working there part-time and Nixon was with Defence technology company, Raytheon. He asked her on a date. A week before the COVID-19 March lockdown, they moved in together. Jack, who Keighran co-parents with Kathryn, now has a sister – Nixon’s daughter Isabelle, also three.

“He’s a very good Dad,” says Nixon, who says she was attracted to Keighran’s motivation and caring nature. So whirlwind was their courting that she learned a lot about Keighran by reading proofs of the book. “I cried the first time,” she says.

It is a remarkable story, one which Keighran would love to talk over with his grandfather; let him know what his grandson has become, what he stands for. Leadership is important to Keighran, a skill tested in the battlefield and honed while studying an MBA at Queensland University of Technology at the urging of Quentin Bryce. He graduated in August and is a full-time account manager at Thales.

He’s dad to a “cool little dude”, has a role in a little girl’s life, and is determined to be a far better father than his own. And through the VC, he’s a representative of the men and women who serve in the Defence forces. “If I stand for anything, it is for them.”

His ambition is to become director of the Australian War Memorial. He’s on its council now, alongside friend and media magnate Kerry Stokes and former prime minister, Tony Abbott. “I have seen the good that place does for veterans, certainly for those who are suffering. They go there and they feel included again.”

That day on a hill in Afghanistan had a profound effect on the life of the rangy boy from the bush but he’s looking forward, not back. “I’ve proven to myself I can do things and it has nothing to do with the VC.

“It’s given me opportunities but I have now proved to myself and others that I’m more than one day. One day doesn’t define who I am.”

Courage Under Fire by Daniel Keighran VC, published by Macmillan Australia; $50 hardcover, out October 27