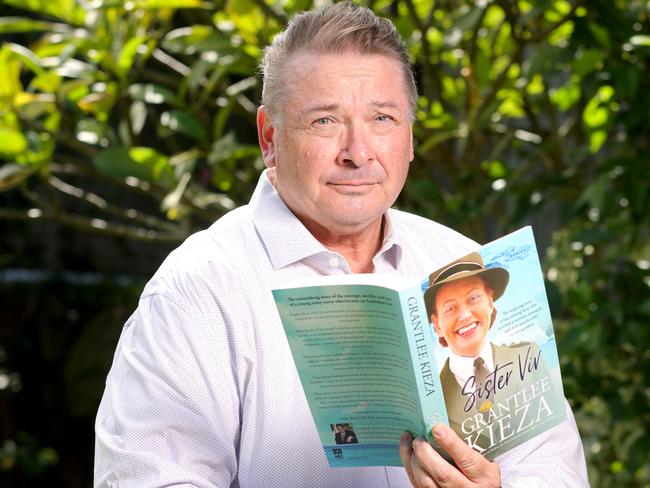

Australian nurse Vivian Bullwinkel’s heroics revealed by Grantlee Kieza in Sister Viv

How nurse Vivian Bullwinkel survived one of World War II’s most horrific events is a remarkable Australian story. Less well-known is that she headed back into a war zone three decades later, as Grantlee Kieza relates in this extract from Sister Viv.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

On a cold Sunday night in April 1975, Vivian Bullwinkel was settled into an easy chair in front of the large log fire in her matron’s apartment at Fairfield – her chihuahua, Tao, curled up at her feet. On the television was yet another news bulletin about the chaos of the war in Vietnam. Viv found the images of screaming women and children and homes on fire very unsettling. She had seen enough of all that as Japanese forces attacked Singapore in 1942: an invasion that led to the massacre of Australian nurses on Bangka Island, where Viv was left for dead, before spending her next three years in hellish prison camps.

It was 10pm when the telephone rang. Something about the late hour and the disturbance to her quiet time unnerved her. Viv answered the call but she could hardly believe her ears. Thirty years after Viv had come home from a war, she was now being asked to go back to another.

**

Looking down at the war-torn countryside of the Mekong Delta, Viv’s heart raced. The inside of the RAAF C-130 Hercules transport was spartan and as hot as a sauna. Seated against the walls of the massive aircraft in drop-down aluminium seats were a dozen nurses. The engines were so loud no one could hear each other speak. Apart from a cleared walkway through the middle, most of the interior space was stacked floor to ceiling with packing cases containing food and medical supplies.

It was 17 April 1975, and Viv, now almost sixty, was one of twelve volunteers flying through hostile air space as part of a lifesaving mission to rescue Vietnamese orphans, as communist forces approached Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). A fighter jet was their escort.

Vulnerable to enemy anti-aircraft fire, the Hercules made a steep descent into Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airfield as Viv and her colleagues prepared to race into action. Awaiting them would be harrowing scenes of distressed babies and small children, many ravaged by hunger and disease and close to death.

Viv was taking part in the second Australian mission of Operation Babylift, the name given to the mass evacuation of babies and children from South Vietnam. The rescue had started two weeks earlier, on 3 April, with the Allied forces planning to evacuate more than 3000 children to Australia, the United States, France, West Germany and Canada.

The dangers were not just from the communist forces. In the first mission of Operation Babylift, a mammoth C-5A Galaxy had experienced an explosion just twelve minutes after takeoff that tore apart the lower rear fuselage. The Galaxy had landed in a rice paddy, skidded for 400 metres and became airborne again before crashing into a dam wall and bursting into flames. There were 176 survivors but 138 people, including seventy-eight children, died.

The following day, 5 April, 215 children and babies, some in cardboard boxes serving as makeshift cots, had arrived at Sydney Airport after a nine-hour flight on a chartered Qantas jumbo jet from Bangkok. The children ranged in age from three days to fourteen years. The most seriously ill travelled in a makeshift infirmary ward in the first-class cabin. When the aircraft touched down, ninety babies were rushed to the Royal Alexandra Hospital in a fleet of ambulances. Others, many suffering from tropical diseases, were ferried to the North Head Quarantine Station.

It was late that same evening as Viv was relaxing by the fire that she’d received a telephone call from the Fairfield hospital’s medical superintendent, Dr John Forbes. He’d asked her to put together a team of volunteer nurses to travel to Saigon as soon as possible to collect 200 more war orphans.

![04/1973. Vivian Bullwinkel (third from left), matron of Fairfield Hospital, the sole survivor of the Banku Island massacre of Australian nurses in 1942.Anzac Day. Melbourne. Neg: FD25047[Sun 26/4/1973]](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/ecb4f06e07759eb9bc798bbeaad29e99?width=650)

The volunteers were required to have some flying experience, some experience in South-East Asia, current cholera and smallpox inoculations and a current passport, which narrowed the field considerably.

With Sydney’s North Head Quarantine Station now at capacity, a new destination for the orphans was needed, and the Fairfield hospital was the ideal destination. Dr Forbes would lead the mission, and Viv volunteered to fly there too.

‘I had no intention of staying out of this one,’ Viv recalled, ‘because I felt that I had experience in the tropical areas of wartime conditions and all the medical superintendent wanted of me was to be able to feed a baby and change a napkin and I said, “Yes, I think I can do that”. So I went.’

Viv was an old hand at war conditions and evacuations under gunfire.

She did not have enough nurses at Fairfield to spare, so more were recruited from the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital. With her close friend Val Seeger, a senior Fairfield nurse, Viv oversaw the packing of the necessary medical kits and prepared to brief the nurses the next morning. Those who needed them were given cholera vaccinations. Then the doctors and nurses boarded a bus and journeyed up the Hume Highway to arrive in Sydney late that evening.

The plan was to board a flight to Bangkok the next day to meet an RAAF Hercules for the flight to Saigon. But there was a breakdown in negotiations with the South Vietnamese

government and the trip was cancelled.

Another flight was eventually rescheduled, this time with only seventy-five orphans, instead of the original 200. They were all under ten years old and 60 per cent were babies and toddlers. Viv took a huge quantity of supplies, including anti-diarrhoeal medicines, saline solution – and a way of introducing it to babies suffering from dehydration – plus glucose and oral electrolyte fluids. There were disposable nappies, milk products, and plenty of feeding bottles. There were also large quantities of baby and toddler food plus meals for the older children.

The anticipated medical problems included tuberculosis, malaria, gastroenteritis, dehydration and intestinal infestation. As it turned out, the orphans’ illnesses proved to be more varied and serious.

A very early start was made on 16 April, with Viv and the others travelling to Tullamarine Airport to board another chartered Qantas jet for the 11-hour flight to Bangkok. Arriving late that evening, Viv was immediately bowled over by the 32-degree heat and humidity, of the kind she remembered from her prison camp ordeal in Sumatra.

An overnight stop had been arranged by the Australian Embassy, though an official seemed more concerned about the team incurring expenses rather than with their mission. Everyone wanted an early night, because the next day would be a long one. Viv had divided her staff into two teams. She would lead Team One, which would travel to Saigon on the Hercules the next morning to sort the orphans into broad categories based on their age and the amount of medical care they needed. Team Two would stay in Bangkok and convert the Qantas jet into a mobile hospital and nursery.

Early the next morning, Viv and eleven others in Team One departed for Saigon on the Hercules with Wing Commander John Mitchell at the controls. For two hours the nurses endured the heat, humidity and noise inside the Hercules, as well as the clear and present danger that they could be shot out of the sky. As Wing Commander Mitchell made his final approach to Tan Son Nhut he came in low and fast to avoid possible ground fire.

As the machine rolled to a stop, the sound of gunfire echoed in the distance. Reminded of the horrors she witnessed on Bangka Island, Viv shuddered. As soon as the doors of the aircraft were opened and the cargo ramp lowered, Wing Commander Mitchell told everyone to make a getaway as quickly as they could.

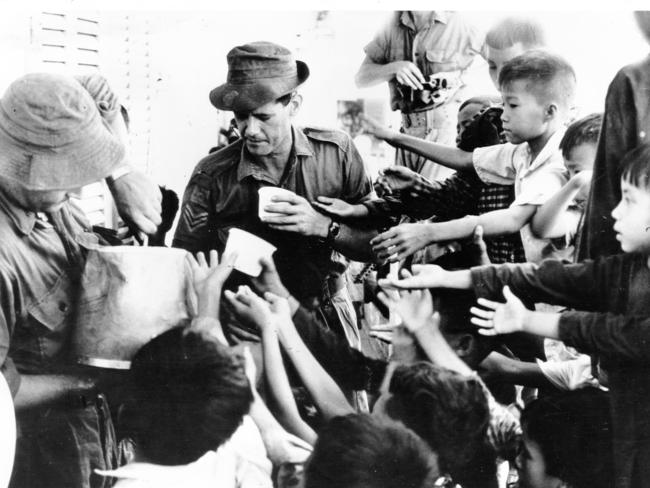

With the North Vietnamese army closing in, there were already two Hercules waiting on the tarmac. Remnants of the Australian Embassy in Saigon had already loaded the babies on one aircraft and the toddlers and children on the other. Both aircraft had their engines running and their cargo ramps down, and people were dashing everywhere. Parts of the airfield were already under attack. The great propellers of the Hercules whirred to the sound of gunfire and mortars, and within minutes of the Australians arriving in Saigon both aircraft were in the air.

Viv would never forget the rows of cardboard cartons, in each one a small babe, in some two or even three fragile specks of humanity with pleading eyes and pot bellies of starvation and

sickness. Most of the babies showed glaring signs of malnourishment, a condition with which she had once been all too familiar. One baby listed as eighteen months old was in fact an undernourished three-year-old.

Viv suspected that they had all kinds of diseases – tuberculosis, worms, shigella and other parasitic conditions, scabies, boils, abscesses and infections caused by lice and by poor nutrition and hygiene. Some were beset by chickenpox and whooping cough. Some had respiratory infections. All were suffering from fear and trauma. One of the orphans, an eight-month-old boy, died on the way to Bangkok. Later, tests would show that 15 of the

orphans were carrying hepatitis B, four were carrying salmonella and one had been born with congenital syphilis. Several had pneumonia.

Once in Bangkok the children were loaded onto the Qantas jet, which took off into the dark night sky, bound for Melbourne. The jet was much more comfortable than the big, loud Hercules and many of the children and babies relaxed and fell asleep. Some, though, were ravenous, gulping down the food they were offered and looking for more. All night, Viv and her team tended to the little ones, feeding, changing nappies, and making them all as comfortable and relaxed as they could.

The children were all victims of hunger, trauma and starvation. Even the toddlers had learned to fight for survival. The children gobbled down their food and some hid handfuls of rice under their seats for later use. When one of the nurses bent down to pick some up she received a karate chop to the back of the neck from an infant warning her to stay away.

After nine hours, the Qantas flight touched down at Melbourne’s Tullamarine Airport in the foggy dawn of 18 April. The plane taxied to a long line of waiting ambulances. One reporter said the orphans of Saigon had arrived like ghosts in the mist.

The orphans reached the Fairfield hospital at 6.30am. While there was now no shortage of food, many remained severely traumatised by the war. Most wouldn’t sleep near windows nor in cots. ‘But as the days went by,’ Viv explained later, ‘they gained in confidence, and they were different kiddies. They relaxed and were gorgeous and outgoing.’

The evacuation from Singapore in 1942 had been a disaster but, 33 years later, the evacuation of these orphans was a great success. Some of the babies were already too sick to recover, however, with four of the sickest children, all in intensive care, passing away within two months of their arrival. By then, most of the 70 children who had survived were living with adoptive families. Viv stayed in touch with many of them and, as the years passed, she would delight in all their achievements.

This is an edited extract from Sister Viv, by Grantlee Kieza: available now, published by HarperCollins.

More Coverage

Originally published as Australian nurse Vivian Bullwinkel’s heroics revealed by Grantlee Kieza in Sister Viv