Housing crisis looks set to deepen as Government figures don’t stack up

It’s plaguing all of Australia and now worrying figures show that the crisis looks set to deepen.

Economy

Don't miss out on the headlines from Economy. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Real estate has long been at the heart of everyday Australian life. But in more recent times the issue of housing has taken on an even greater level of urgency and importance, not seen to this degree in decades.

Amid what some are calling the worst housing crisis in living memory and double digit increases in asking rents, the simple calculus of how many homes the construction sector needs to build to keep up with demand has become a key question.

Earlier this week, the Albanese government provided a vital piece of the puzzle in the form of its mid-year budget update, which contained Treasury’s latest estimates on where net migration would sit across the forward estimates. From this we can make a very rough estimate on how many homes need to be built to keep up with the growing population.

Before we get into the numbers, it’s worth noting that the forecast figures are far from set in stone. At last year’s mid-year budget, Treasury estimated that net overseas migration would come in at 235,000 in 2022-23 and 2023-24. It is now estimated that the figure for 2022-23 was 510,000 and 375,000 for 2023-24.

As for the natural increase in the domestic population (births minus deaths), we’ll be pencilling in a figure of 132,000 which is the average level of annual growth seen over the past five years. It may come in lower but conversely, it’s entirely plausible that other inputs may come in higher.

It is here that an important distinction needs to be made. When the government and much of the commentary talks about building 200,000 or 1.2 million homes, that is referring to the number of newly built residential homes. But 200,000 newly built homes doesn’t necessarily mean that overall dwelling stock expands by 200,000 homes.

Due to the impact of knockdown rebuilds, homes being demolished to make way for new projects and a number of other factors, the most recent ratio of net growth in dwelling stock to newly completed homes is 0.85. In short, for dwelling stock to grow by 100 homes in net terms, 117.6 new homes need to be completed.

How many homes do we need to keep up?

The following assumes that all homes built in net terms are being added to overall dwelling stock as full-time homes, where people would live through most of the year, not as holiday homes, holiday lets or simply sitting empty. This is not especially realistic, but nonetheless provides a conservative ballpark estimate of what is required.

Based on the average household size of 2.5 persons, the five year average in the natural increase in the population and the migration forecasts laid out in the mid year-budget, the required amount of new homes to keep up with projected population growth is as follows:

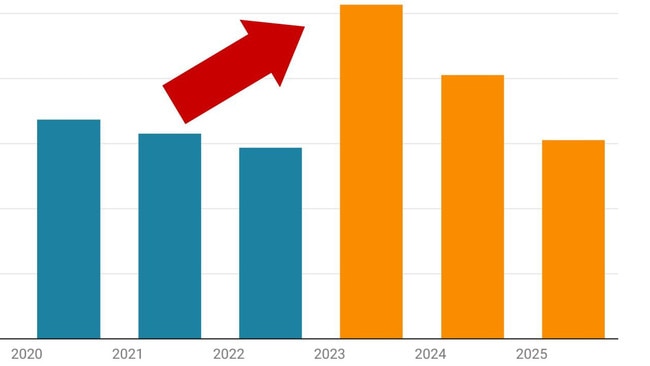

2022-23: 256,800 net new homes, 302,000 new completions

2023-24: 202,800 net new homes, 238,500 new completions

2024-25: 152,800 net new homes, 179,700 new completions

According to data from Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in the year to June 2022, a little under 147,000 homes were added to overall dwelling stock in net terms. Based on a very rough estimate derived from the historic ratio of dwelling completions to net dwelling stock growth, in the year to June 2023, approximately 148,300 homes were added to net dwelling stock.

At the peak of the growth in the ABS data series which unfortunately only covers the past seven years, the peak rate of dwelling stock growth was 199,000 in the year to June 2017.

How many homes are going to get built?

So far estimates on the number of number homes being built for the calendar year 2024 are relatively few and far between. But one firm, SQM Research, which focuses on the property sector among other things, recently included an estimate in their housing ‘Boom & Bust’ Report. SQM concluded that around 153,000 residential dwellings would be completed. This would represent the weakest level of dwelling completion activity since 2012.

Once the impact of knockdown rebuilds and other drivers is factored in, we come to a figure of a little over 130,000 homes added to net dwelling stock.

Considering that over 150,000 additional dwellings in net terms are required during the lower migration levels projected for 2024-25, the growth in the housing deficit appears set to continue.

How far behind are we?

It’s here that a challenging reality must be confronted. While the numbers suggest that growth in dwelling stock is set to fail to keep up with population growth for at least another 12 months, the nation is already well and truly behind the eight-ball.

According to a recent analysis by NAB, there is currently a structural shortfall of 120,000 homes. In the words of NAB’s head of market economics, Tapas Strickland, Australia was starting from behind even before the borders reopened.

“The ratio of population per new dwelling approval is running at 3.6, the worst in the history of the series that dates back to 1984,” Strickland said.

How long could the housing crisis last?

Given the high number of variables and the sheer range of possible outcomes, this is the hardest question of all to meaningfully address.

More Australians could be forced to move into share housing and back in with family, which could reduce demand for housing and rental accommodation. However, this isn’t a terribly desirable solution for many. It leaves more people in circumstances they would prefer not to be in and creates a sizeable pool of pent-up demand for rentals and housing more broadly should it become more affordable relative to incomes.

But if we assume that sharehousing and living with family recovers to roughly the trend seen prior to the pandemic, and then stays there, the end of the path of the current crisis may lay at the end of the decade.

With the construction sector in the doldrums for a multitude of reasons from inflation to waning demand at current prices, a return to pre-Covid levels of dwelling stock growth appears to be several years away, provided the economy does not fall into a recession.

Ultimately, it all comes down to the basics of supply and demand. We know very roughly what demand may look like for several years to come, but the outlook for net dwelling stock growth is more unclear and the estimates that we do have, suggest that the short term view is not terribly positive.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as Housing crisis looks set to deepen as Government figures don’t stack up