You won’t believe how much these half-forgotten bands get paid

POPULAR music festivals like Soundwave are going broke, and you can blame the bands. Some who have not released albums for years are demanding millions to show up.

Media

Don't miss out on the headlines from Media. Followed categories will be added to My News.

HOW much do bands get paid? A surprising leak shows acts who have not released a decent album in years demanding staggering sums that are sending music festivals broke.

The ugly demise of Australia’s Soundwave festival has given us a peek at how much cash once-great bands demand. It is a fortune.

The Smashing Pumpkins played the four dates of the 2015 Soundwave — Adelaide, Melbourne Sydney and Brisbane. I asked someone to guess how much the Pumpkins might command for a gig these days. She guessed $30,000. A lot of money, sure.

The correct answer: $1.27 million. That’s how much the act was supposed to get for the four dates. And they weren’t even going to be the highest paid.

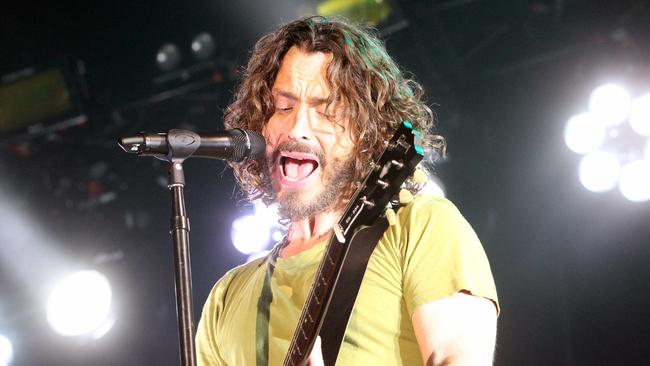

Soundgarden — a band from Seattle who have released one album in the last 19 years — was supposed to get $2.1 million. Slipknot was supposed to get $1.65 million. Faith No More was supposed to get $750,000.

(Not every nineties band gets quite such huge chunks of cash. Area 7 — an Aussie band who I remember fondly, are owed $7600.)

Now that the company operating Soundwave has gone into voluntary administration, all those bands are hoping to collect is cents in the dollar.

The fees some old acts can demand is enormous. The reason is twofold.

One, they made their money when you could still sell CDs for $30. They have their fortune and they don’t need to work unless the price is right.

The second reason is their fans. Once excitable teens now have solid jobs. Many can easily find $200 to drop on reliving the cherished music of their youth. (This economic truth is why so many festival headliners are grey-haired and backstage has more arthritis medication than cocaine.)

When Woodstock was held in 1969, the bands were hot at the time. The top paid act was Jimi Hendrix, who got $US30,000. (That’s $US180,000 in today’s money.) Next was Creedence Clearwater Revival on $US10,000. ($US60,000 in today’s terms.)

A lot has changed. These days, big, old acts hold festivals hostage. Without them, tickets won’t sell. Their pay demands push the festivals to the very edge, and festivals go broke with alarming frequency.

Here’s a very abbreviated list of Aussie music festivals that no longer operate:

• Big Day Out

• Parklife

• Harvest

• The Great Escape

• Good Vibrations

• Homebake

When festivals fail to make money, it causes problems. My favourite such story is of the son of the Viscount Trenchard, Alex Trenchard (who was once pageboy to the queen).

He holds an annual festival on his father’s property, Standon Lordship, which has featured acts such as Florence and the Machine. The event grew and grew and in the late 2000s began to run up debts. Trenchard junior defrauded his employer (Tesco) to pay them back and, in 2011, ended up in jail.

Thanks to his understanding parents, the festival continues. But festivals are replaceable. When one falls down, another pops up in its place.

The failure of a festival can, however, be especially bad news for smaller bands who were relying on them to earn a little money and win new fans.

New bands don’t get to sell CDs. They have to grind away on services such as YouTube and Spotify where — it is said — a track can be played more than 100 million times and win its writer just a few thousand dollars.

These days the money is in touring. But for a small band, even touring is not always profitable. Here’s a story of a band that toured for 28 days across America, with a sponsor. They made an $11,000 loss.

Small bands depend on festivals to find new fans and make a decent fee, while festivals in turn depend on big bands. To try to feed the enormous fee demands of these mega bands, festivals are getting creative.

You can now buy “premium” tickets to almost all festivals, as they try to wring more money out of those who can pay. For example, the US Coachella festival offers “safari tents” with air-conditioning and side-of-stage access for $3250.

Festivals also court sponsors, who stick their brand on everything.

But the smartest festivals — and the safest ones, financially — are ones that have inherent value of their own, so people want to attend no matter who is playing.

The South by Southwest festival in Austin Texas bills itself as a place where new bands are discovered. This means most acts play there for free. SXSW charges up to $US750 for a ticket, and gets thousands of people along. They’ve got it figured out.

Burning Man festival in Nevada is even more radical. They don’t have musical acts. The crowd shows up — more than 60,000 people paying $US390 — and entertain themselves.

That crowd includes some big name musicians, including P. Diddy and Jared Leto. That’s one way to break the monopoly of the wealthy old bands. Turn them into paying guests.

Jason Murphy is an economist. He publishes the blog Thomas The Think Engine. Follow him on Twitter @jasemurphy.

Originally published as You won’t believe how much these half-forgotten bands get paid