Lady Chatterley case scandalises high society as gardener lover faces arson charge

THE alcohol-fuelled love affair between a rich widow and her gardener drew comparisons to the risque exploits in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, but the real-life version had a fiery end.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN the book Justice Denied, leading QC Bill Hosking looks back at some of the fascinating cases he has been involved with in his career as a criminal barrister.

Offering an insight into the way the justice system works, and the colourful characters drawn into it, he acknowledges: “Justice is an elusive end, and not always achieved.”

In this extract on the 1970s’ case of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover”, he reflects on one jury decision that “left me and my client stunned”.

Road trip riddle: Mystery haunts a dark outback road

Undercover agents: The day Russell Crowe walked into ‘a hit’

***

Lady Chatterley’s Lover was the romantic, even dashing, literary creation of the novelist DH Lawrence. In the tale, the gamekeeper, Oliver Mellors, enjoyed a torrid love affair with the noble lady of the house, Constance Chatterley. The climax, if I may so describe it, was romantic. It was first published in 1928, but banned in Australia and many other countries because of its explicit story. Far too risqué for the times.

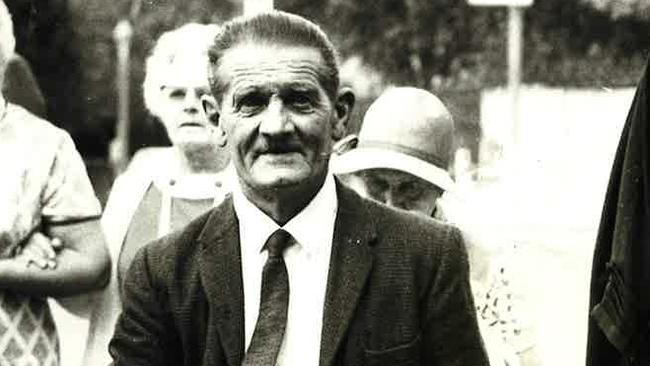

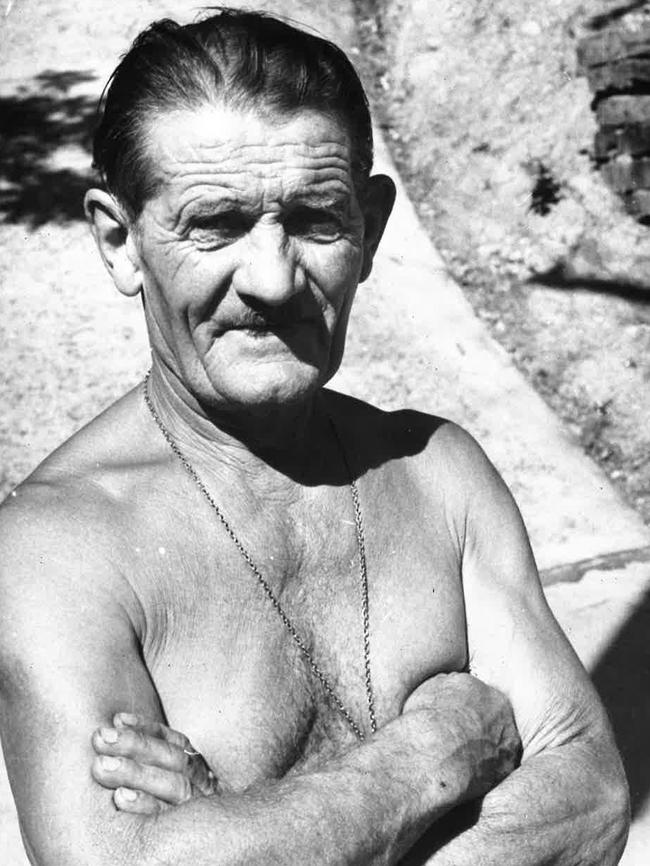

My client, Jozef Kiraly, was a humble gardener retained in that capacity by the dowager lady of a Sydney northern beaches mansion, Mrs Prudence Lydia Washington Carter. Her residence was in the fashionable Prince Alfred Parade, Newport, overlooking the glistening waters of Pittwater, which is dotted with recreational sail and motor boats. Their relationship grew from friendship to seduction and a love affair. Kiraly was Mellors to Mrs Carter’s Lady Chatterley.

Kiraly and Mrs Carter’s friendship dated back almost twenty years to when her husband was alive. After Mr Carter’s death, they had drifted apart. Mrs Carter had been a widow for almost four years when she encountered Kiraly again, by chance, at the Newport Hotel.

Mrs Carter was a handsome and lonely lady living in the large mansion and soon invited Kiraly to move in. He readily agreed. Having been her husband’s gardener he was engaged to do gardening for her, but only one day a week. Free board, with his own room, was offered in lieu of wages. A talented cook, he would also do most of the cooking.

He was called ‘Joe’ but she was never to be called ‘Prue’— she was ‘Mrs Carter’. She was sixty-two years old. Jozef Kiraly was two years her junior.

As time went on, the mistress–servant relationship softened to become very friendly, eventually moving on to seduction and a love affair. Kiraly began to refer to Mrs Carter as ‘darling’. Tending the flowers was less fun to the couple than sharing a whisky and red wine in bed, mornings and evenings.

The development of a love triangle shattered that tranquillity. Another, younger, man called Alan arrived on the scene. When Mrs Carter taunted Kiraly about her younger man, his pathetic reply was, ‘Forget me, I am a poor man.’ Later, he would modestly proclaim that, as a lover, ‘Nobody ever looked after her like I did.’

On the night of 16 May 1973, the couple shared a bottle of Hungarian liqueur as a farewell drink. Kiraly had accepted Mrs Carter was moving on with her life, and they slept together, but there was no sex.

The events of the next few hours are uncertain.

The following day, 17 May, Mrs Carter woke Kiraly shortly before 5am by stroking his face gently and suggesting they share a cup of tea. Mrs Carter took her tea with the conventional milk and sugar, and copious amounts of whisky. This predilection of having whisky in her tea existed well before Kiraly was on the scene. In Mrs Carter’s own words, ‘it just warmed me … it is smoother’. Kiraly also drank tea, but usually followed it with red wine. This was their daily ritual. Normally, Kiraly did not match Mrs Carter’s consumption of alcohol. He was employed as a stonemason and during the day he did hard physical work. A heavy, pre-dawn tipple was not a good idea.

On this day, however, Kiraly and Mrs Carter consumed a half bottle of whisky between them and Kiraly had foregone his usual habit of having red wine. For Mrs Carter, the situation suddenly became ugly. Kiraly threw her bedclothes off and, after a struggle, he tied her hands and ankles with rope. According to Mrs Carter, Kiraly retrieved a four-gallon drum (roughly eighteen litres) of petrol from the garage and ‘sloshed’ the contents all over the bedroom carpet. She was terrified. After a time the tension subsided and Kiraly freed Mrs Carter from bondage. The couple then had yet another cup of tea and talked.

Mrs Carter later said Kiraly produced fourteen of her Mandrax sleeping tablets. She consumed seven of the tablets and he the remainder, which he spat out. The next thing Mrs Carter knew her house was full of thick smoke. Kiraly lay unconscious on the floor next to the empty four-gallon petrol drum. Fire brigades and an ambulance rushed to the scene. Kiraly was soon on his way to hospital for treatment. For a day, his life hung in the balance. Most of the fire damage was to the furniture and carpet in the main bedroom, which was totally destroyed. Ironically, the double bed escaped almost unscathed, but for a little scorching.

It was mid-afternoon when Sergeant Stuart MacLeod arrived at the scene. Mrs Carter was still wearing her nightie. MacLeod noticed reddish rope-burn marks on her wrists, and bruises and abrasions on her body. Detective Sergeant Mervyn Schloeffel of the Special Crime Squad from headquarters soon took charge of the case due to its gravity.

Upon Kiraly’s release from hospital he was arrested and charged with arson. The charge was further aggravated by the fact that the police alleged the fire had been deliberately lit with Mrs Carter still inside the room. At the time, an arson charge carried life imprisonment. Kiraly was in big, big trouble.

Kiraly had lived in Australia for almost twenty years, having emigrated from Hungary, and spoke English quite well. Even so, from the outset, he asked Detective Sergeant Schloeffel for the assistance of an interpreter before being questioned. Police readily agreed. He had never been in trouble with the police before and perhaps didn’t trust he could explain himself clearly in English. This caused a delay of some hours while an official Hungarian interpreter was located.

Detective Sergeant Schloeffel’s questioning of Kiraly was searching but fair. Kiraly admitted being drunk at the time, restraining Mrs Carter and fetching the petrol, which he splashed about the bedroom. In his explanation to police, he blamed Mrs Carter for mixing the alcohol to make the prescription drugs cocktail. Kiraly’s portrayal of the liquor and ropes as a prelude to playful sexual servitude was not an instinctively appealing explanation. The uncontested evidence was damning, but he refused to admit to lighting the fire.

To police, this was not a trivial domestic dispute: the ropes and the petrol smacked of malice and revenge. And Kiraly was the only person likely to have lit the fire — there were only two people present in the house, and Mrs Carter had no motive to torch her own home. Kiraly’s admissions leading up to the fire became damning circumstantial evidence of planning and premeditation.

The four-page record of interview was read aloud by the independent interpreter and signed by Kiraly and Detective Sergeant Schloeffel, who handed Kiraly a copy, which he was able to give to his solicitor. The signed interview did him no favours, but that was not the fault of the police. His conduct had been completely out of character.

***

The trial was listed for the District Court of New South Wales, a little over eighteen months after the fire, in January 1975. Hearing the matter was Judge Muir, a senior judge who had a reputation for being wise and even handed, always preserving the balance. Jozef Kiraly faced two charges, arson and assault. The arson charge was for setting fire to the house; the charge of assault came from tying up Mrs Carter’s hands and feet prior to lighting the fire.

Mr Kiraly was not a wealthy man and, as such, received my services through the grant of legal aid to private solicitors. From a legal point of view, Kiraly’s defence presented formidable difficulties. The obvious obstacles to an acquittal were the mere presence in the bedroom of the petrol and the rope. These items were totally inconsistent with desire and tenderness, but consistent with force and hostility. The Crown relied upon them as proof of the jealousy of a jilted lover. They didn’t agree with Kiraly’s explanation that tying Mrs Carter’s hands and feet was a prelude to a pre-dawn episode of consensual bondage. The details of any sadomasochistic behaviour between the grand and buxom Mrs Carter and the diminutive and humble Mr Kiraly would have tested the jury’s imagination. Whisky, red wine and sex would have been avant-garde, but bondage and discipline would have been an unknown pastime on the Northern Beaches in the seventies.

The Crown had taken the trouble to brief Mr JK O’Reilly, a senior barrister at the private bar, himself destined for judicial office. His presentation of the Crown case was extremely persuasive. He made pointed reference to the availability of ropes in the bedroom, adding the use of petrol negated any explanation of impulse and pointed to premeditation. Mr O’Reilly relied upon, as the Crown was fully entitled to do, the strong circumstantial evidence of guilt against Kiraly.

Mrs Carter presented herself well as the key prosecution witness. She was impressive and dignified, and it was obvious the misfortune that befell her that day was not of her making. Her only crime, if you could call it so, was having had an affair with my client. It was, however, he that let her down and not the other way around. With Kiraly’s statement, all the circumstantial evidence, and now Mrs Carter’s testimony, I had a difficult job ahead of me.

Under cross-examination, Mrs Carter readily agreed with me that she and Kiraly had formed a relationship which she enjoyed. Kiraly described her as his girlfriend and Mrs Carter had no problem with that. She also liked a drink, with the clock not governing the hour of commencement of consumption. Brandy or whisky were her favourite additions to tea. Nor did it impair their ‘enjoyable sexual relationship’. The 5am partaking of scotch or brandy, or on Kiraly’s part, red wine, gave the expression ‘early opener’ a new dimension.

After the Crown rested, it was my turn. My reference to Lady Chatterley in my address to the jury was very much an unintended throwaway line in outlining the accused’s defence. My emphasis was on the important fact that the bedroom indiscretions were adult and consensual. To state the obvious, they bore little resemblance to the plot of the DH Lawrence novel other than the two participants were the lady of the house and her gardener.

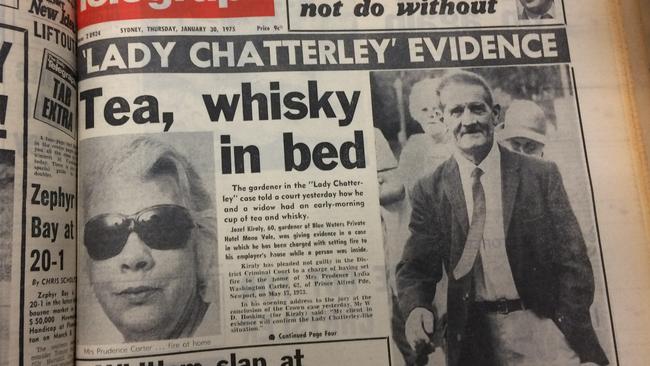

The Sydney afternoon tabloids, however, latched on to the description and gave front-page prominence to the trial. Not because of any legal significance, but for its salacious romantic overtones. Even the conservative Sydney Morning Herald prominently carried accounts of the lovers’ trial in detail.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

Mr Kiraly was no Errol Flynn, Sean Connery or Daniel Craig. Nor was he a tall man. His appearance exemplified modest mediocrity, certainly not the profile of a dashing, violent lover. The lady of the house, Mrs Prudence Lydia Washington Carter, had perhaps been a shade indiscreet in embarking upon this affair, but hardly deserving of the public censure and massive public embarrassment which followed. She was a respected local lady and deservedly so. As I told the jury more than once, and with a distinct lack of originality, the District Court of New South Wales was not a court of morals.

My argument lay in my client’s legal responsibility while under the influence. In those days, self-induced intoxication, through alcohol and/or drugs, could diminish legal responsibility completely. It could also reduce the length of any gaol sentence depending upon the degree of impairment, not increase it. Kiraly’s excessive consumption of alcohol, producing a deadly cocktail when mixed with the sleeping pills, was a crucial factor on the issue of intent. The undeniable fact was Kiraly had consumed so much, in the form of drugs and alcohol, he was found unconscious, lying on his back, and was taken to hospital close to death. Could he have been in control or conscious of his actions?

Kiraly had the option of either giving a dock statement, without having to undergo a cross-examination, or facing interrogation in the witness box. He elected to go into the witness box; there was nothing to lose. We hoped his responding to the Crown’s case under cross-examination might help the jury understand Kiraly’s situation at the time of the fire and have sympathy for him. If not, his testimony might at least create an element of doubt.

O’Reilly’s skilful cross-examination of Kiraly swept away all the drama beloved of a paperback novelist of love and liquor. He focused devastatingly on his admissions contained in the record of interview. As O’Reilly unsympathetically pointed out, these were Kiraly’s own words translated by a reputable, official interpreter.

The mere description of Kiraly as a gardener did not do him justice. There was more to him than that. In the witness box, facing the examination and cross-examination, Kiraly handled himself well. There was something about him you couldn’t help but like; he was a very charming and likeable person. He told of meeting Mrs Carter, who picked him up in her car at the Newport Hotel. He described the couple’s drinking habits, which were a shade unconventional, particularly first thing in the morning. He also told the jury that, on the day of the fire, he remembered nothing more than tying Mrs Carter up and pouring the petrol. This was honest and truthful, but hardly helpful to his cause. Kiraly’s record of interview with the police was explanatory, but not exculpatory. However damaging Kiraly’s responses were to his case, the manner in which he answered had you believing he was telling the truth. He really had no memory, and he didn’t accept he had started the fire.

Where a person of good character is accused of a serious crime, they are entitled to have that fact placed before the jury. Kiraly was facing life imprisonment. Seldom have I been able to call more impressive character evidence than in this case. First up was Navy Commander Ronald Ware, a marine surveyor and industry executive, who had known Mr Kiraly for sixteen years. He was eloquent in his praise of Kiraly’s honesty, dedication to charity and community spirit. Commander Ware had raised bail for Kiraly on his arrest. A family friend, Dr Stephen Koraknay, the mathematics master at the exclusive Knox Grammar School, had also known Kiraly for sixteen years and gave evidence.

Other solid family and surf club friends of longstanding joined the extraordinary line-up of character witnesses. The final witness was solicitor Mr Peter Montgomery of Newport, who had known Kiraly since the age of seven, describing him as ‘like a grandfather’ and ‘embarrassingly generous’. Even the police, when asked by me in front of the jury, spoke well of him from a character point of view.

With such prominent community support it was pleasing Mr Montgomery and his friends were content for a public defender to act for Kiraly.

***

All the evidence had been given. In Mr O’Reilly’s closing address to the jury, his admonition not to be deflected from their duty by sympathy was firm. He told them their duty was to rely on the evidence, not newspaper headlines. There had certainly been a lot of those.

Judge Muir’s summing up disappointed me. It focused squarely on the admissions Jozef Kiraly had made to the police and not denied by him, and the tying up of Mrs Carter, and the rope burns and abrasions she had suffered. Judge Muir told the jury the Crown was fully entitled to rely upon the signed record of interview, which were Kiraly’s own words translated by the official interpreter requested by him. The judge added that any doubt about whether the police had treated him fairly or not was laid to rest by the fact neither Kiraly nor his barrister had made the slightest criticism of the police conduct in the case.

On the other hand, the judge did emphasise the importance of Kiraly’s good character and the impressive evidence called to support it. He reminded the jury of the alcohol consumption by both, and the resultant confusion in the house on the day of the fire.

When the jury retired to consider their verdict, Mr O’Reilly told me he thought the judge’s summary of the defence case was overly favourable to the defence. I guess both sides feeling the other side fared better is perhaps the hallmark of the perfect summing up.

The verdicts were returned after an incredibly brief retirement of thirty-five minutes. At the end of the day, this jury was not deflected from its duty. There were two counts in the indictment arising out of events in the bedroom. The jury acquitted on the first count of arson, a result that left me and my client stunned, but convicted on the second, which was common assault. As the jury foreman gave the verdicts, it was put to Judge Muir that the jury gave ‘a strong recommendation for leniency’ in sentencing Kiraly for common assault.

Against the odds, against a strong circumstantial case, against an almost full admission to the charge, Kiraly came out a winner. Kiraly was released by Judge Muir on a good behaviour bond. The judge said he did so after taking into consideration the jury’s mercy recommendation and Kiraly’s previous good character. Judge Muir was not bound by the jury’s recommendation, but he did take it into account.

The trial had a sad and unhappy postscript. The fire caused a great deal of damage. Gossip forced Mrs Carter to move away from the mansion with sea views and the large manicured garden. She told the Daily Mirror, ‘I certainly know who my friends are after this case … I was actually the injured party, but I have been made to feel I am on trial.’ She was accurately described in the same tabloid as ‘a handsome grey haired widow’.

The Daily Mirror devoted almost its entire front page of 30 January 1975 to the verdict. The headline read, LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER FREED. ‘HAPPY’ SAYS THE GARDENER … ‘UNHAPPY’ SAYS THE WIDOW.

The Mirror went on to report, ‘Outside the court, Mrs Carter denied she was a Lady Chatterley but agreed she had an affair with Kiraly. “I’m very unhappy” she said. “I’ll never see him again. It’s been a terrible and embarrassing experience for me.”

‘Kiraly said, “I am happy with the result. If I had gone to jail I would never have come out alive. I am too old.”’

The last word rested with Mrs Carter who told the Mirror, ‘My only crime was that I was found out.’

Plainly, Mrs Carter had committed no crime and, as she claimed, was very much the injured party.

• Justice Denied by Bill Hosking and John Suter Linton, published by Harlequin, is available here and where all good books are sold. RRP $29.99

Originally published as Lady Chatterley case scandalises high society as gardener lover faces arson charge