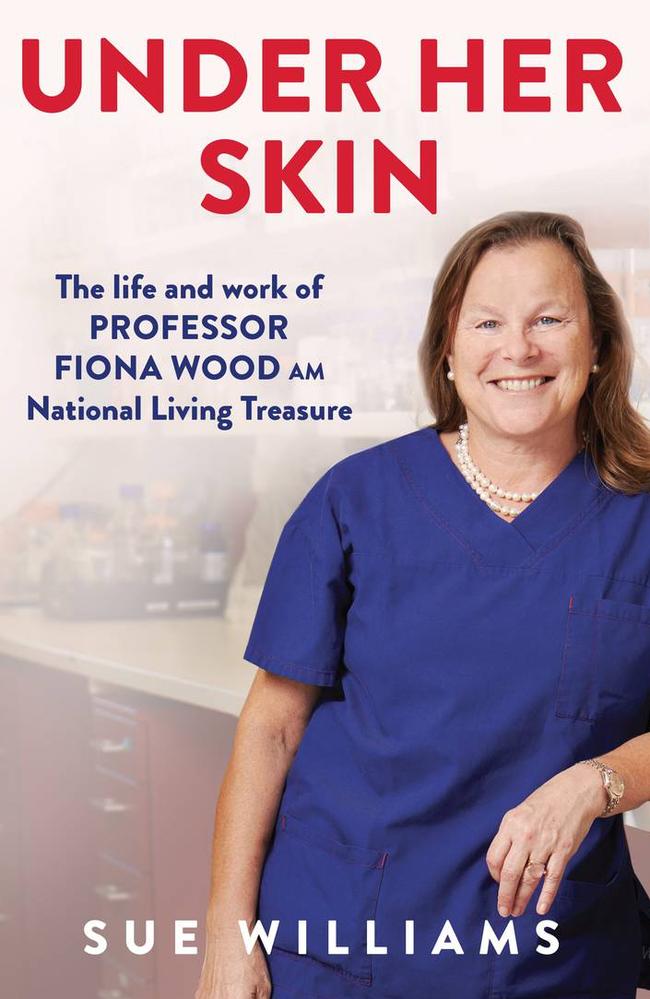

An extract from Professor Fiona Wood’s new biography Under Her Skin

A new book has revealed what happened inside the walls of the burns clinic treating Aussies injured in the Bali bombings. Read the extract.

This October marks 20 years since the 2002 Bali bombings, which killed 202 people including 88 Australians.

Burns specialist Professor Fiona Wood revealed to News Corp some of vivid, “harrowing” memories that still haunt her to this day.

She also has opened about her experiences overseeing recovery and treatment plans of injured Australians, many of whom had burns to more than 50 per cent of their bodies, in a new book.

Here is an extract of the biography – Under Her Skin: The Life and work of Professor Fiona Wood, National Living Treasure by Sue Williams.

Fiona Wood grew up as the fifth generation of a coal-mining family in the North of England, trained as a plastic surgeon, specialising in burns and migrated to Australia in 1987, becoming one of the heroes of the horrendous Bali bombings 20 years ago.

Seeing her parents trapped into that mining life instilled in Fiona a strong determination to succeed in everything she turned her hand to — for the very best chance of getting out. Her parents impressed that on their four children at every opportunity.

‘The greatest gift in life is to enjoy your work,’ their dad Geoff used to tell them. ‘You spend so much of your time at work, it’s important you find value in what you do.’ His eyes often had a faraway look at that point, as if perhaps reflecting on his own bleak lot in life. ‘So everything you do, you have to try to do to the best of your ability.

‘Study hard at school and play hard afterwards. Never settle for second best. That’s never good enough.’

‘I learnt from Mum and Dad that there was no point getting up in the morning just to be average,’ she says. ‘That’s a waste of energy. It’s always about being the best you can be; not being satisfied with second place. I knew they hadn’t had the opportunities to better themselves, but I knew there’d be opportunities there for me, and I wanted to make sure I was ready to seize every single one.

‘I look back and think I was probably hyperactive but I managed to channel that in a positive way through a capacity for hard work, and being naturally competitive in everything I did, and having a lot of energy to pour into everything. I realised the worth of what my parents said, and felt that if something was worth doing, then it was worth doing well. I felt an almost sort of obligation to do the best I could, and be the best version of myself that was possible.’

On October 12 2002, three bombs are detonated in Bali, killing over 200 people and injuring hundreds more, many of them Australians. Fiona’s trainee surgeon Dr Vijith ‘Vij’ Vijayasekaran is there on holiday, and heads straight to the hospital, and applies for permission to operate on some of the survivors.

Burns patients can lose as much as 20 litres of fluid in 24 hours and so an IV drip becomes absolutely necessary to restore blood pressure and maintain the vital functions of kidneys and other organs. At that stage, word thankfully comes through that Vij will be permitted to operate. He knows they are both in desperate need of escharotomies — the surgical procedures to cut away the mass of burnt tissue to relieve the pressure caused by the thickening of the skin and swelling that can prevent movement and the flow of blood, and cause serious tissue damage.

‘When you get a full-thickness burn, it’s like putting a tourniquet on your arm because the skin becomes like leather and cuts off your circulation,’ Vij says. ‘And then you end up losing limbs. So, it’s important to perform escharotomies where you basically need to incise through the burn to release the tension. It’s like cutting a rubber band, but you’ve got to do it the whole length of the limb.’

An Englishman living in Bali — whom Vij suspects is an IV drug-user as he seems to know so much about surgical procedures — organises for scalpel blades to be brought in. There are no handles available but Vij makes do, operating on both 29-year-old Sydneysider Jodie O’Shea and Perth mum Tracy Thomas, 41. ‘Jodie didn’t wince once when I was performing the escharotomies and she was really the most courageous patient,’ he says. ‘She was obviously very unwell, suffering acute renal failure, but was such a nice girl, and smiled almost throughout the whole ordeal. We then also operated on Tracey.’

Another visiting surgeon from Wollongong joins Vij, and the pair assess more patients, taking off their dressings to check their burns and other injuries and performing escharotomies where necessary.

‘I lost count of how many escharotomies we did. We had such limited equipment and supplies, but we did our best. There was no anaesthetic but I would explain that it was to save their limbs, and that someone would hold them while I operated. They all understood the situation and what we had to do. We had no analgesia, no blood products, only one oxygen mask that had to be shared between patients, only one or two pairs of scissors per ward to cut dressings … The patients were all very brave.’

He also meets two of the Australian Defence Force attaches who have flown down from Jakarta and begins trying to work out who should be airlifted on the first flights back to Australia. It is basic triage, but a heartrending task. Anyone who looks as if they won’t make it, is pushed down in the pecking order. Anyone with a chance is promoted. Jodie, who seems so sick she might not last too much longer, is added to the top of the list so she’ll arrive in Perth as soon as possible. If she doesn’t make it, then at least she might be able to have her family by her side on home soil.

Any friends or family who are with patients are instructed on how much IV fluid their charge will need — too little can lead to multiple organ failure, and too much can increase swelling — and to check and squeeze the bags to push more into them if necessary. Vij seizes a permanent marker and runs around writing the amount of fluid each patient needs on their bedsheets, while Priya sets up a high-dependency unit to manage the most critically ill.

Listen to the AFP’s new podcast Operation ALLIANCE: 2002 Bali Bombings

Back in Australia, Fiona Wood had been organising everything that was needed to keep the survivors alive.

It was the biggest ever peacetime emergency evacuation of Australians from overseas, and the largest air evacuation since the Vietnam War, with more than 100 patients — most with horrendous burns, terrible injuries and many fighting for their very lives — airlifted to safety.

But what made the biggest impression on Fiona that day was something much more intimate. ‘The thing that overwhelmed me when I saw the patients, was the look of relief on their faces,’ she says, quietly. ‘That’s the one image I’ll remember forever. They were home: they felt safe; they felt secure. But we knew their battles had only just begun, and we got straight to work.’

With most foreigners now being extracted, the hospital and clinics in the neighbouring areas were better able to cope with the smaller number of Indonesian casualties. Meanwhile, eleven patients arrived in Perth direct from Bali, among them Jodie O’Shea, the young woman Vij had been so impressed with. Her burns had, back then, looked the most severe at around 90 per cent, but her demeanour, her humour and her obvious courage had made Vij hope against hope that she’d be able to beat the odds. On her arrival in Perth, everyone immediately understood why. The emergency staff were all similarly charmed by her smiles, her polite manner and her grace, and were devastated to realise she was unlikely to make it; her injuries were just too overwhelming. But when she died within a few hours, it was, at least, in her mother’s arms.

Two other critically ill women also came in that first contingent to Fiona’s burns unit. Tracy Thomas had been holidaying with a friend when they ducked into the Sari Club for a drink. She’d sustained burns to 60 per cent of her body, severe blast injuries and terrible shrapnel wounds. Her three daughters, Carla, Kimberley and Lauren, had rushed to be by her side while the doctors assessed her, stabilised her and decided what to do next. Then there was Simone Hanley, 28, with 75 per cent burns, whose kidneys had stopped functioning. She was put into an induced coma and placed on a ventilator because of the heat damage to her lungs. She’d been in Bali with a group of girlfriends and her sister Renae Anderson, 30, who was still missing.

Shortly after that was done, 17 more survivors arrived from the 61 flown direct to Darwin. That made it a total of 28 patients with major burns in Fiona’s care, the most of any hospital and just over half of the total 52 who were critically ill with burns injuries. With vast areas of their bodies scorched and blackened, gaping shrapnel wounds, deep glass cuts, appalling blast injuries and tissue damaged by the shockwaves from the bombs, their care was a daunting task. ‘It was like working with the survivors of a war zone,’ Fiona says. ‘These were devastating, complex injuries, way beyond any injuries I’d ever seen, and had to treat, in the past.

Burn injuries weren’t the only issues for those wounded in the Bali bombings.

There were particular problems with the Bali patients that hadn’t been encountered before. There was shrapnel embedded in many of their limbs, which had to be dug out for fear of further infection; the interior workings of one of the bombs had apparently been smeared with faeces, which created more contamination. Many of the patients had suffered burst eardrums from the explosion so couldn’t hear or communicate effectively. Some patients had been flung, or had jumped, into pools when they’d escaped the burning buildings and the water hadn’t been clean, which caused more infection, or had been driven to hospital in the back of dirty vans or garbage trucks. Many of the bugs the patients carried home with them as a result were completely unknown in Australia, and proved resistant to regular antibiotics. Already, complications such as renal failure, thermo-regulatory shutdown and trauma shock were setting in.

Some of the operations were so complex that they were becoming marathons, performed by surgeons working side-by-side in that torrid 32-degree heat. Each one also necessitated around six nurses to help, with dressings being opened and then redone as soon as individual wounds had been operated on. There was a need for lots of skin grafts as many of the patient had so little of their own left, while Fiona used the ReCell skin kit, with Cellspray.

Edited Extract – Under Her Skin: The life and work of Professor Fiona Wood, National Living Treasure by Sue Williams pub by Allen & Unwin October 5 2022 rrp$34.99

More Coverage

Originally published as An extract from Professor Fiona Wood’s new biography Under Her Skin