Bloody family ties in Australia’s dark past exposed in The Suicide Bride

Three desperate children run to a neighbour with horrific news: “Mammy and Daddy are dead.” It’s 1904 and an all-too-common case of murder-suicide, but there’s a wider family story, raising stark questions about criminality and the notion of nature versus nurture. WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

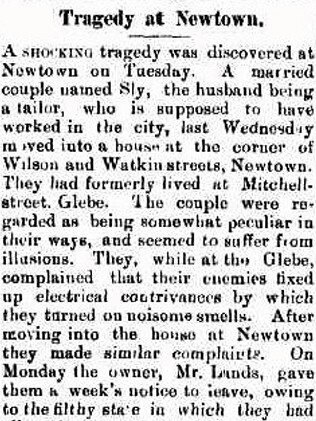

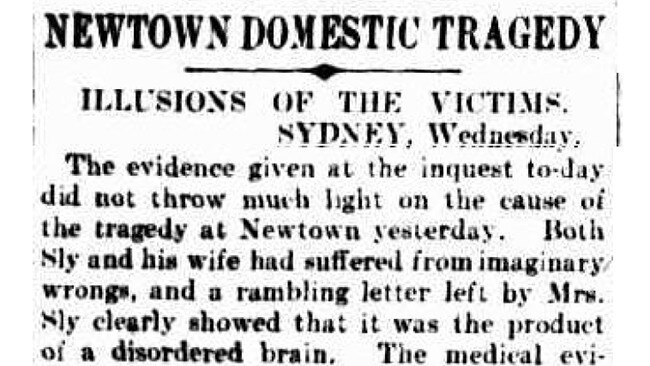

When Alicks Sly killed his wife Ellie and then himself in 1904, it was sadly just one of many murder-suicide tragedies in turn-of-the-century Sydney.

But the couple’s deaths were also part of a wider family story that raises questions around criminality and the notion of nature versus nurture.

True Crime Australia: Bitter pill for drug testing advocates

Toyah Cordingley murder: Top cop reveals challenges six months on

In The Suicide Bride author Tanya Bretherton picks apart the fate of the Slys, their three orphaned sons and the broader relationships that may have played a part in such a grisly end.

Here, in two extracts for True Crime Australia, she recounts the moment the parents were found dead by their children and the observations of the first policeman on the scene.

Sargeant Matthew Agnew had been told there had been a death in the Newtown house, but had been given no warning of murder or the bloody sight that awaited him.

WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT

WHEN four-year-old Mervyn Sly woke on the morning of Tuesday, 12 January 1904 in the inner city of Sydney, he did not know how close he was to death. While he had been sleeping peacefully on the ground floor of his home, a two-storey terrace house at 49 Watkin Street, death had arrived, and stayed. It now lurked silently on the top floor.

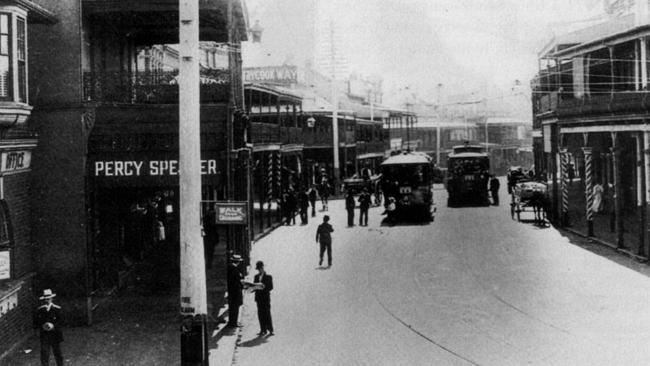

Beyond the boy’s bedroom window, the borough of Newtown was charged with the restless and noisy energy of a busy weekday morning in metropolitan Sydney. Trains rattled loudly on their approach to Newtown Station. The air was filled with the sweet and heady smell of yeast from the bakery across the street. The flat and dull strike of a forging hammer pealed out from the blacksmith with the rolling rhythm of an off-key church bell. Even the soft snorting of horses from the stable on Wilson Street could be heard from the Sly residence on the corner. None of it, however, had been enough to stir the young boy from slumber.

Book extract: Tiny clue to Suitcase Baby’s killer

It was around 9.30am. Long lancet-shaped windows, arched like those found in a church, cast pillars of warm light across Mervyn’s face. Dust rose from the rag-filled mattress on which he slept and floated up in the air, then fell with the softness of light snow. An open window briefly swept a fresh cool breeze off the Pacific Ocean into the room.

The young boy had gone to bed without dinner, and the grumbling of his stomach finally shook him from sleep. As soon as he opened his eyes, he leapt from bed and ran outside to seek out his older brothers: Bedford, eight, and Basil, six. He found them at the home of Mrs Shaw, a neighbour.

The Sly family had lived on Watkin Street for less than a week, but in that time they had made an impression on their new neighbour. The Slys were Catholic, and this alone made them strange, according to Mrs Shaw. But other things struck her as odd. Mr Sly was a nervous man: he complained about the house, about rapping and tapping in the walls, wires on the roof and intruders at night. On occasion he even complained about his children. Bedford, the eldest son, also told tall tales about the goings-on in the house. He had told Mrs Shaw, in more detail than she would ever care to know, that he and his father had seen dark figures moving about the house at night.

Mrs Shaw had spent most of the past week chasing the boys off her property; she had also become unwillingly involved in the comings and goings of the Sly household. She had looked after the children when their parents went out — which was often. She had provided the address of a local doctor when the youngest child, Olive, had fallen ill — this too seemed a burden. It was lucky Mrs Shaw had been willing to help. Olive had almost died, and remained in hospital recuperating. Mrs Shaw had even fed the Sly children. The three boys complained that the bread and butter in their home tasted grainy, that it was jagged and bitter on the tongue. It burnt them, they said. Bedford had taught his brothers how to steal bread from the pantry and sprinkle it with sugar to make breakfast. When they could not find fresh bread at home, Bedford taught his brothers how to beg. For the past week, this activity had almost always led straight to Mrs Shaw’s door. On 12 January, sometime around midmorning, discussion between the three boys turned to the issue of their parents. Bedford said he had seen their father that morning when he had woken up. Their father had been dressed in his suit, and Bedford had seen him stride through the house with razor and strop in hand, shoes on and laced up, vest buttoned.

Bedford told his brothers their father must have been going to work.

For some reason, Mervyn decided to return to the house alone. The little boy, dressed in a loose-fitting romper styled like a sailor suit, ran exuberantly through the terrace house. Finding no one in the kitchen or sitting room on the ground floor, Mervyn sped towards the steep and narrow stairs that led up to his parents’ bedroom. Mervyn most certainly would have gathered speed at the bottom to ensure his small feet and short legs could make the ascent.

Then, at the top of the staircase, the boy abruptly stopped, unable to comprehend the extraordinary scene that confronted him.

Perhaps he noticed the way the sunlight came streaming in through the curtainless windows. Perhaps he noticed that the sunlight reflected off the wooden floor and glowed red with the blood that saturated almost every surface in the room. Or perhaps the young boy was fascinated by the sticky sensation and sound of his feet as they tracked across the red liquid that surrounded his mother’s body.

Mervyn went in for a closer look. His mother was lying across a mattress on the floor. A spongy and slippery coil of muscle and connective cartilage lay in the space where the smooth skin of her neck had once been. The blood had pooled, soaked into the mattress and surrounded her head in a perfectly round congealed crimson aura. This must have been a terrifying scene for a young Catholic boy, familiar with sculptures and reliefs of the Virgin Mary and her sacred halo. He looked at a horrifying re-imagining of his mother: not Our Lady the Virgin, but a bloody Mary lying half naked on the bedroom floor.

Not able to fully understand what he saw but believing his mother desperately needed help, Mervyn ran back downstairs and outside to the comfort and safety of his brothers. He tugged at Bedford’s sleeve. ‘Come and see, there is something wrong with Mammy,’ he said urgently.

Bedford, taking his responsibility as an older brother very seriously and being the closest thing to an adult, went to see for himself. Basil took Mervyn’s hand. The two boys waited patiently, and fearfully, in the lane outside their home. Inside, Bedford made the second terrible discovery of that morning. He found not just their mother but also their father, in a similar condition on the bedroom floor. Somehow, little Mervyn had not noticed that his mother was not alone.

Follow: True Crime Australia on Facebook

It took longer than it should have for the boys to get help. This was not because Bedford hesitated — he ran as fast as he could to Mrs Shaw’s front door. But she did not believe him. When he opened with, ‘Mammy and Daddy are dead’, she quickly drew what she believed to be the only logical conclusion: he was lying. Just another strange story from this strange boy, she thought.

But Bedford did not give up. He insisted his parents needed help.

Mrs Shaw did not enter the terrace house to investigate Bedford Sly’s claims. Instead she grabbed the arm of a passing stranger in the street, asking them to send word to the police. She allowed the three boys to play nearer to her yard, and she told them not to worry. This was the extent of the comfort she showed them.

The three young brothers waited at the crossroad of Watkin and Wilson. Bedford stood in the shadow of the towering two-storey family home. Mervyn was bathed in sunlight. Basil waited between the two, flanked by light on one side and shadow on the other.

THE CALL-OUT

Agnew had seen just about enough. He abandoned his reconnaissance of the ground floor and decided to take a cursory look upstairs to assess the damage. As he circled the banister and began to climb, he stopped.

There were red puddles on the stairs. Blood dangled in a heavy droplet from the top step and had pooled on each one leading down. In a reflex action, Agnew rested his hand atop his revolver and proceeded cautiously up the stairs.

At the top, he stopped again. For a moment he thought these hardwood floors were also covered with a decorative oilcloth rug. A red one.

There was so much blood it coloured the floor with a macabre design. It was dark brown in thinner patches where the warm air had dried it more rapidly, while deeper plum and currant tones were present where the pools remained thick and wet.

Then Agnew noticed them. When he did, he was shocked at himself for overlooking them.

One man. One woman. Face up on the floor, a short distance from each other. Both completely soaked in blood. Their throats had been cut, though the woman had been subjected to far more savagery than the man.

In Agnew’s long career he had seen blood, and plenty of it. He had seen murder. He had even seen suicide, both failed and successful attempts. Some fourteen years before, down the street from where the sergeant now stood, thirty-year-old William Carlton had attempted to end his life by cutting his throat with scissors. His housemate found him passed out on the floor. Agnew’s quick dispatch of Carlton to the hospital had seemed to save the man’s life, but he had lost too much blood and died the next morning.

Agnew believed he knew what had happened here. A cut-throat razor was still grasped in the man’s coiled right hand. The two arms of the device were folded out like a pair of compasses about to take measurement. The cuts on the man’s neck were short and jagged, just as they had been with William Carlton.

The woman’s condition was a very different matter. A deep swipe of a cut, right across the neck, had created a most bizarre sight. The spooling thread of her windpipe looked like the thick string of a torn necklace, with her head resembling a threaded bead on the brink of breaking loose and rolling away.

Agnew believed he knew what he was looking at, because he had seen something like it before. Almost twenty years earlier in Newtown, a mathematics teacher at the elite Newington College, Arthur Blyth, had killed his wife, Edith, with a razor, and then himself. When Agnew had arrived at the Blyths’ home that day, the scene had been one of absolute mayhem. Neighbours were out on the street, eager to hail anyone for help. Edith’s mother wailed while she cradled her dead adult daughter in her arms. That scene had made sense to Agnew. It had been loud, chaotic and unholy, screaming at him in a way that seemed in perfect proportion to the crime. But there was a quietude here, in this home on Watkin Street, that made his skin prickle like gooseflesh.

• The Suicide Bride by Tanya Bretherton is published by Hachette Australia. $32.99. Out now.

If you or anyone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

Originally published as Bloody family ties in Australia’s dark past exposed in The Suicide Bride