The Blight Files - Part 6: Sprays, pump-ups and stories which are now football folklore

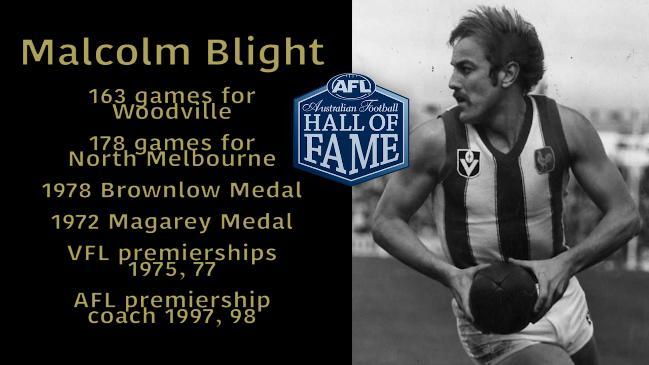

ECCENTRIC ... it is said again and again of Malcolm Blight. But though his methods were often unconventional, the master coach knew just what strings to pull to motivate his men.

AFL News

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Blight Files: Part 1 — The start of greatness

- Blight Files: Part 2 — Getting Cats up to scratch

- Blight Files: Part 3 — Messiah’s glorious return

- Blight Files: Part 4 — ‘Blighty almighty’ conjures miracle

- Blight Files: Part 5 — Third flag one climb too many

ECCENTRIC. It is said again and again of Malcolm Blight.

Some of the legendary Malcolm Blight stories could fill a book.

“That’s why I’ve never written a book,” says Blight. “But the stories are out there ... a lot of them get mixed up, wrong dates, wrong times. Sometimes two stories get put together as one — (former Geelong forward) Billy Brownless has made a career out it.”

Blight once declared “95 per cent of me thinks I’m sane; the other five per cent is still wondering.” And he makes no apology for taking a chance on a wild idea. It is the beauty of his genius.

“Sometimes it would be great,” said Blight.

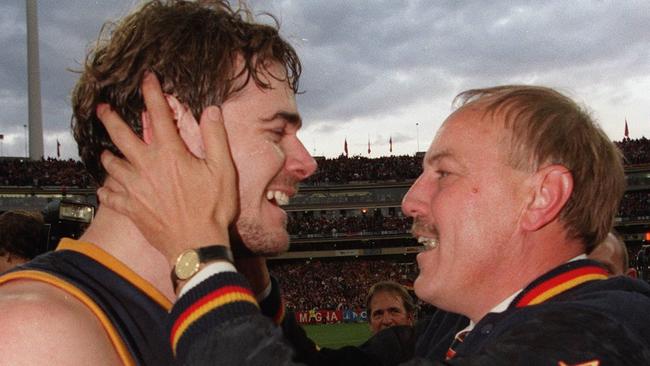

Football’s books are loaded with accounts of his high-risk, high-reward gambles, particularly in Adelaide’s 1997-98 premiership double.

“Sometimes it looks silly.”

Such as the day in 1993 when Blight had the Geelong players from a guard of honour to the Crows team as it came from its changerooms to take the field at Football Park.

Or in 1991 when he demanded Austin McCrabb stay away from the Geelong team at the quarter-time huddle because he had broken a team rule — by kicking across goal — in a heavy loss to Hawthorn at Waverley.

Or the post-game spray of Crows ruckman David Pittman in 1997 — the “pathetic Pittman” blast on national television — after just Blight’s second game as Adelaide coach.

“We’ve all had a spray,” says former Geelong captain Garry Hocking. He copped it at halftime from Blight in 1991 during a game against Footscray for having appeared in a major spread in The Age newspaper “as a new kid on the block” who still needed to prove himself before getting his names in headlines.

Or the day Blight left Hocking on the bench for the last quarter so he could “sit and watch the best players where they run”.

“He was ruthless and scathing,” Hocking said. “But you were absorbed in what he had to tell you.

And if he said jump, you’d ask, ‘How high?’ You might have felt bad at the time, but the next day you knew Blight’s message was the best advice for you.”

One story from Blight’s three dramatic years at the Adelaide Football Club is told repeatedly by his players. It is from 1999 — when the premiership defence is crumbling and Blight was searching for a way to break a losing streak — that had the Crows players turn up at their West Lakes base to find their coach on a ladder in the changerooms.

Blight ordered them to get before their lockers. He then worked his unconventional review one by one.

Premiership captain Mark Bickley was first. Blight’s advice to his hard-at-it skipper was to check if Hawthorn great Michael Tuck had written a book — and to read it to learn how the 426-game Hawk appreciated his “limits” by not mixing up ambition with capability.

Vice-captain Nigel Smart was second. Blight told the defender how he was referred to the “Spaceman” in the coach’s box.

“I’m not sure,” said Blight, “if that is because you are from another planet ... or for all the space you give your opponent.”

Pittman was lined up again for how everything in his life “must be a drama”.

And as fear started to turn into belly ache from the laughter the players were trying to hide, Blight put a serious edge on the session by sacking premiership forward Troy Bond.

“He gave it to me,” Bond recalled. “We’d played Fremantle at Subiaco and they had thumped us (by 39 points). He lined us all up and got the old ladder out.

“As he was going through everyone I was thinking that as I had a hamstring injury — as I normally did — and I had not played, I’m not going to cop it.

“But I’d missed a rehab session. Blight’s eyes lit up. He said, ‘Did you miss a session Sunday ...’

“I didn’t even get a word out. He told me to get my gear, pack it up and go to the Port Adelaide Magpies and ‘I’ll ring you when I want to see you again.’

“He could give you a roasting,” added Bond who was called back three days later “after Blighty had calmed down”.

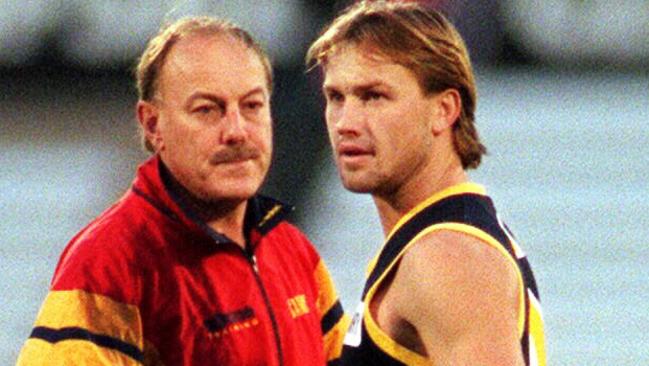

Port Adelaide coach Ken Hinkley highlights Blight’s infamous sprays were also based on finding a way to reignite a player — as he learned at Geelong in 1992.

“I knew what I was walking into on a Monday night because the papers were saying Blighty was going to go after a player,” Hinkley recalled. “When I got to training after work I knew I would be the ‘headline act’.

“He had me in front of the whole team, 40 of my teammates. I thought it was unfair as he pointed out what I had not done and how I had hurt the team. It was tough to hear.

“I thought, he can’t treat me like this. But he did. I didn’t play well that week — and at the end of that game Blighty came at me saying, ‘Well son, that (spray) didn’t work. We’ll have to try something else’.

“I won the best-and-fairest that year (and third in the 1992 Brownlow Medal count),” said Hinkley of the end result from Blight’s eccentric ways.

Blight’s former boss at both Woodville and Adelaide, Bill Sanders, recalls the precursor to the “ladder moment” at the Crows was with the Warriors in the 1980s when Blight at halftime put his team in front of all the club staff in the changerooms at Woodville Oval.

His target was captain Max Parker.

“He had Max stand up and gave it to him,” Sanders recalled.

“But what started as a berating session — and Malcolm could make the paint peel — develop a subtle turn that became a pep talk.

“He had Max floating by the time the team went back on the field. And Max could have beaten the opposition on his own in the second half.

“That was Malcolm. He knew how to man manage — and was brilliant in motivating players.”

FOUR UNFORGETABLE HEADLINES

HOW Malcolm Blight created controversy with four unforgettable moments in his three-year stay as Crows coach.

Pathetic Pittman

GAME 2 of Malcolm Blight’s three-year tenure at the Adelaide Football Club ended in a 28-point defeat to Richmond at the MCG — and the infamous “pathetic Pittman” spray of Crows ruckman-defender David Pittman.

Blight was unaware Pittman had jagged a calf in the first ruck contest — and could not jump. He also was being kept on the field by the bench staff as Adelaide had no back-up ruckman because Aaron Keating, Matthew Robran, Brett Chalmers and Shaun Rehn had missed the game with injury.

“That was partly my fault,” Blight admits. “When I was interviewed after the game by Neil Kerley on television, I said: ‘That was a pathetic quarter by Pittman. We’ll have to live with that but he’d want to improve on it.’

“In the press conference after the game, I said the same thing but didn’t specify that I was just talking about the first quarter.”

Back in Adelaide, Blight and Pittman cleared up the fuss.

“It was a healthy discussion,” said Pittman. “We clarified things. I understood where he was coming from.”

Early exit

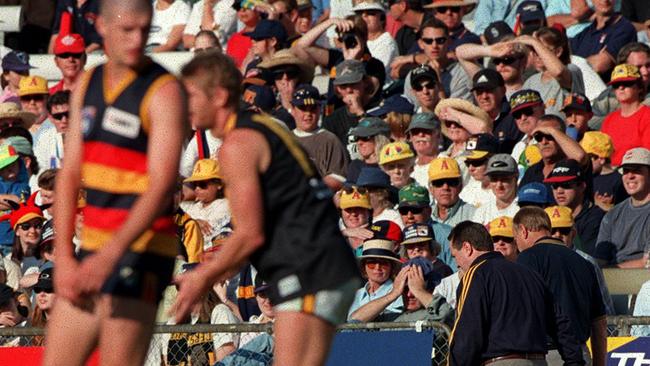

SEASON 2 — and again a loss to Richmond, this time at Football Park, where Blight and his right-hand man John Reid left the coach’s box early — with three minutes still on the clock — walking around the southern boundary.

Reid took the heat at the time, saying he had misread the time clock.

“There was a couple of minutes to go and Malcolm wanted to get back to the room; something had hit him,” Reid recalled. “I said no, but Malcolm came back with ‘We could watch the game as we went along the bounday’.

“He wanted to be in the rooms early — and prepared. He had six things he wanted to put on the whiteboard for the players to see immediately. He wanted them to refocus and was not going to waste a minute.”

The 13-point loss to the Tigers was followed by back-to-back wins and six of the next seven to refloat Adelaide’s premiership defence.

Sacking Modra

COLEMAN Medallist Tony Modra was the scapegoat of Adelaide’s hefty loss to Melbourne in the 1998 qualifying final at the MCG — a result that did not cost the fifth-ranked Crows an immediate exit from the finals.

But Modra, who was played at halfback rather than full forward as the game became a disaster for the Crows after halftime, never again played for Adelaide. He cleared his locker after making his protest about being used in defence at the post-game review with Blight at West Lakes — and missed out on a premiership medal as the Crows organised his trade to Fremantle.

Adelaide chief executive Bill Sanders, who had managed Modra early in his career, recalls sitting in the car park with Modra and his agent Max Stevens with an uncomfortable feeling.

“I was disappointed that happened — and Tony was close to tears,” Sanders said. “Tony had played nine years with the Crows — one short of life membership that meant a lot to him. One of my last acts as chairman was to have Tony get that honour.”

The Ladder spray

MIDWAY through the 1999 season — Blight’s last with Adelaide — the Crows’ premiership defence was in trouble. Adelaide lost to Fremantle in Perth by 39 points — and the players returned to their West Lakes base for one of Blight’s infamous motivational ploys.

Blight was on a ladder in the middle of the Crows changerooms and had the players line up by their lockers for a man-by-man review of their form, careers and even their lives.

Captain Mark Bickley, the first player put under Blight’s microscope, recalls the cutting reviews were so sharp that the players, while in fear of the backlash, were struggling to not laugh.

“He lined us all up,” said premiership forward Troy Bond who was sacked on the spot for missing a rehab session at the weekend when he was to have had physiotherapy for a hamstring injury. He was later recalled to the club.

Blight’s ladder moment is part of the “messiah legend” at the Adelaide Football Club.

The response? Adelaide won the next game beating Collingwood by five points at Football Park.