The Blight Files: Part 1 — The start of greatness

A LEGEND’s path to greatness can have a humble beginning. Sir Donald Bradman had the water tank at Bowral. Malcolm Blight used the clothes line at Davis St, Woodville South. Michelangelo Rucci reports.

AFL News

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SIR Donald Bradman had the water tank at Bowral. Malcolm Blight used the clothes line at Davis St, Woodville South.

“There was a three-foot gap between the shed and the (base of the) clothes line ... it was good for practising your kicking,” recalls Blight.

Bradman improvised, with a short cricket stump and a golf ball — repeatedly hitting the ball against the brick base to the water tank on the porch to the family home. It was the routine that created a phenomenal cricketing legend.

Blight concocted his own drill as a teenager in Adelaide’s western suburbs in the early 1960s. “Bundle together socks ... or a plastic footy, not a real one,” says Blight of his seemingly manic love to kick a football. “And that three-foot gap.”

The “real one” — a “brand, new Ross Faulkner” — was not repeatedly in Blight’s hands until he was nine. A small but quick boy, Blight beat a pack of kids at the back of Woodville Oval when a goal was scored in a SANFL game and the ball went go over the fence. He hid that ball — out of fear the police would find it — for six weeks in the bin that held the wheat to feed the chooks at home.

Legendary is the best way to describe Blight’s path to greatness. He went from those dream-filled weekdays in the backyard of the War Service home near Woodville Oval, to weekends as a teenager always wanting to kick a football with his mates, to the game’s pinnacle.

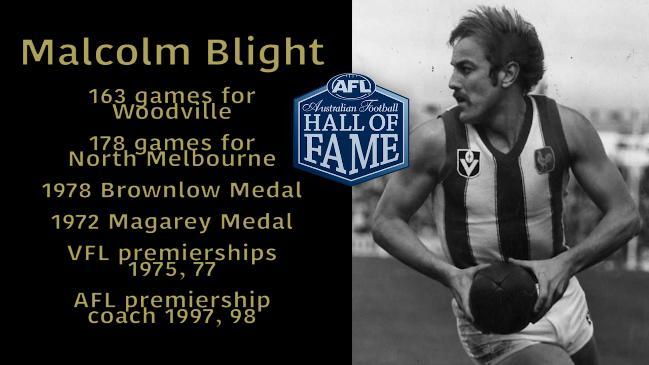

All Blight ever wanted was to play for Woodville. He made it to the VFL. He is now the 27th official “Legend” in the Australian Football Hall of Fame — and second South Australian, following Barrie Robran, to the game’s highest pedestal.

Blight, born February 16, 1950, grew up in Adelaide’s western suburbs in a post-war era when — with no television, no computers and no social media — it was football in winter, cricket in summer. Blight did play district cricket for Woodville, but it was football that commanded his passion.

His uncle, Horrie, coached Woodville to its 1948 amateur league premiership — the only senior premiership won by the club before its merger with West Torrens in the SANFL at the end of 1990.

His father, Jack, played football. But there was no pushing the boy to football. There was no need — the game had won Malcolm Blight’s heart already.

“I was mesmerised by the game,” says Blight. “Besotted by it.”

First, Blight wanted to be at Alberton Oval. He was taken in by the goalkicking dominance of Port Adelaide forward Rex Johns, who kicked 451 goals in his 134 SANFL games with the Magpies from 1954-63.

“I’d go to the game to see the big boy ... and loved it,” Blight recalled. “I loved it. It was amazing. How quick and how big are they, I’d be thinking.”

Then, Blight always wanted to be playing football. Three games on a weekend — at Brompton, at Kilkenny, at Woodville South and eventually at Findon High — to be with “your mates”.

Bill Sanders saw Blight emerge from the so-called grassroots in suburbia to the structured system of an SANFL league club as the teenager in the Woodville junior colts (under-17s). He recalls how the team’s coach George Kersley wrote a perceptive review on Blight as he sent assessment of each of his players to the senior coaches.

“He’s got something ... he’s loaded with latent ability. He needs to be steered,” penned Kersley, as Sanders recalls.

“And the coaches did get on his back, particularly when he ran on his left leg. He’d say it was to develop his left leg. The coaches would say he was overusing the left foot.

“It helped him ... he became a two-sided player.”

Blight made his SANFL league debut in 1968, starting a run of 50 consecutive years in senior football as a player, coach, media commentator, football director and now club ambassador at Gold Coast.

And for years Blight has made one of his lines among friends at parties a play from Ian Day’s commentary of the 1969 boilover at Woodville Oval where the Peckers beat the star-studded Sturt side that had won the previous three SANFL premierships ... and was to win the next two.

“Blight soars like a 747 and bulldozes that goal through,” said Day.

Earlier this month a Woodville supporter sent Sanders a 20mm film of the game.

“Ian Day is the caller,” notes Sanders. “And he does say, ‘Blight soars like a 747 and bulldozes that goal through’ just as Malcolm has always said.”

Within three years Blight had put his name on the Magarey Medal honour board with Robran and four-time winner Russell Ebert to start the long-running debate on which of the trio is the greatest footballer SA has ever produced.

A TALE OF TWO CLUBS

MALCOLM Blight had his first All-Australian blazer in June 1972 before he had a Magarey Medal as the SANFL’s best player — and his 100-game milestone at Woodville.

Those career markers also were preceded by calls to the VFL after the 1972 Australian football carnival in Perth — first from Footscray and a week later from North Melbourne.

And Blight stayed at Woodville for another 18 months, despite the prospect of more money in the VFL than the $500 he banked in his Magarey Medal season in 1972 and the grand plan to make the Kangaroos a premiership powerhouse, as club boss Ron Joseph detailed at breakfast in Adelaide.

“I wanted to be able to say I had played 100 games with a club — I felt I owed Woodville something after winning the Magarey Medal,” said Blight.

Bill Sanders came to fully appreciate Blight’s devotion to Woodville — “his club,” as Sanders puts it — when he lured Blight back from North Melbourne in 1983.

In the early 1970s he had watched Blight be attached to the club by his family history, his mates . and the card games in the Woodville clubhouse on Thursday night as the league selection committee went about picking the 20 for the weekend.

“North Melbourne,” says Sanders, “was where Malcolm made his influence on a football game known. And there was pressure to perform as another South Australian going to the VFL. He knew what it meant.”

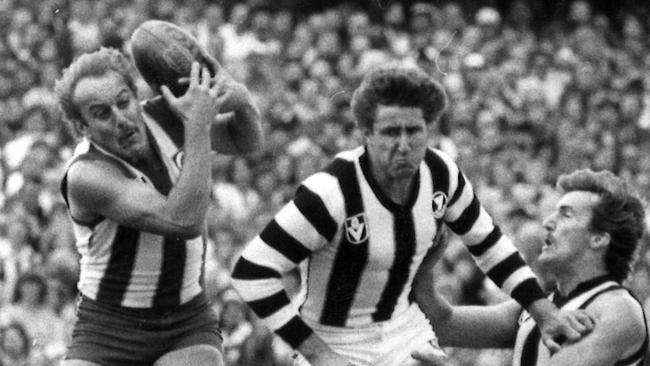

The Australian Football Hall of Fame records Blight played 178 VFL games for North Melbourne from 1974-82.

He became the first South Australian to complete the Magarey-Brownlow double in 1978. He won two VFL premierships, 1975 and 1977, to fulfil the vision Joseph had put to him while many considered Blight foolish to align himself with North Melbourne as the Kangaroos won the wooden spoon and just one match in 1972.

He topped the VFL goalkicking list in 1982 (94 goals) — after he had been sacked in 1981 as the last playing coach in VFL history.

But the resume does not tell of how Blight had to overcome prejudices against South Australians in the VFL, the wrath of North Melbourne coach Ron Barassi and his own free spirit to make his name in the big league.

“I was asking myself, ‘Do I really fit into this place?’,” said Blight who was not only starting a new football adventure but also his married life with Patsy.

“For me, the questions were: ‘Are you suited to the Melbourne lifestyle and Barassi’s approach?’ For a while I was thinking, ‘Jeez! What’s all this about?’”

Blight is the first to admit he would have frustrated his coaches with his laconic ways. Barassi was no exception, but he also lit a fire in Blight rather than burnt out his boyhood love for a game.

“He gave me some of the biggest sprays of my life,” Blight said of Barassi. “But the discipline that ‘Barass’ imparted was probably something I needed at the time as a young player.”

Not every chapter in Blight’s 50-year journey in senior Australian football is, as Blight puts it, “a bowl of cherries”.

The first nightmare was in 1981 when Blight succeeded Barassi as playing coach — and lasted just 16 matches with a 6-10 win-loss count before his sacking to be replaced by Barry Cable.

“I did the job as well as I could have at the time,” said Blight, “but I didn’t do it as well as someone else could have.

“I was the last bloke to pull on a jumper and point the finger at the same time. No-one has been silly enough to do it (in the VFL-AFL) since.”

TOMORROW: Part 2 - The Geelong years