Over-officious umpiring is changing AFL – for the worse | Graham Cornes

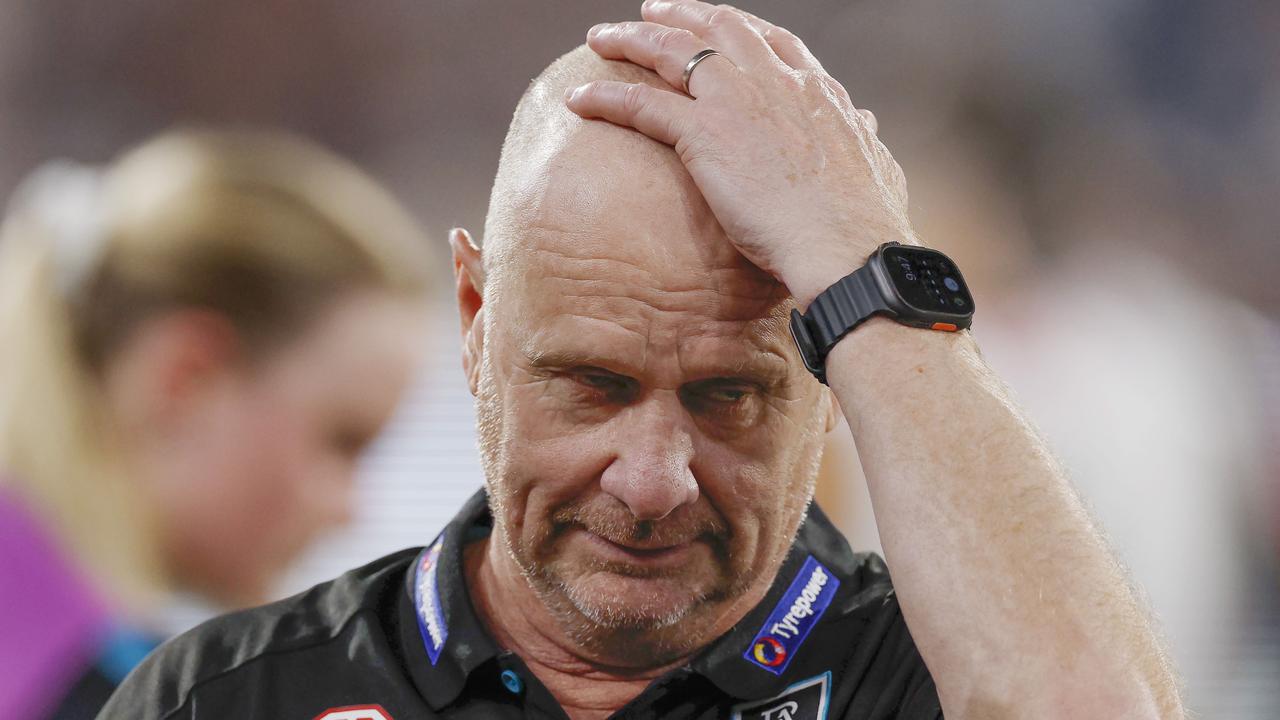

AFL needed to change – but these over-officiating umpires just cut all aggression from footy, writes Graham Cornes. Just take this week’s farcical Giants game.

Expert Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Expert Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

How do we define the fabric of the Australian rules football? I started to write that it was once a “man’s game” that tested the extremes of traditional masculinity, but daring to write such a thing would have any writer outed and cancelled.

The premise of it simply being a man’s game has long been overtaken by new values and an inclusiveness that gives women and previously oppressed minorities their overdue status. “Traditional masculinity” as we would like to remember it espouses strength, resilience, valour, chivalry, larrikinism and generosity linked to mateship.

Unfortunately, it also disguises or tries to excuse the traits of “toxic masculinity” be they sexism, racism, misogyny or alcohol abuse. Historic poor behaviour of star footballers (and other sportsmen), if it wasn’t ignored, was concealed. Today’s footballers are men with better and broader values than their fathers, uncles and grandfathers but the game has lost something in that transition.

The officious over-umpiring and the AFL’s haste to sanitise the game has stripped it of characteristics that made it one of the toughest games in the world to play. The AFL, be it driven by its Commission or subsequent administrative regimes, is undermining the spirit of the game founded on aggression and intimidation. Those concepts don’t ignore fair play but the game isn’t fair any more.

Much of it has to do with the ridiculous over-officiating of the game, which plunged to farcical depths in last week’s GWS v Carlton match, when Stephen Coniglio was penalised for umpire dissent.

This was no raging hysterical abuse of the officiating umpire, rather an almost polite inquiry as to why his perfectly executed tackle, which caused an opponent to illegally dispose of the ball, wasn’t rewarded with a free kick. What were these offensive words? It was a simple, polite question: “Why wasn’t that a free kick?” No swearing, no demonstrative aggression, just a simple question. The free kick awarded to Carlton in the goalsquare, resulted in a goal at the most crucial stage of a vital game.

Melbourne legend, Gary Lyon, now one of the game’s most astute commentators reflected the feelings of most football lovers when he said with bewilderment: “A free kick for that?”

We now have four field umpires on the ground at any one time. Three was one too many and now with four it hasn’t improved.

The fact the AFL, in its review of the match, validated the umpire’s reaction further demonstrates it fails to appreciate the public resentment to game-changing over-officiating.

If anything, with its dogmatic protection of the umpires, the blind endorsement of the match review officer and the tribunal, it is increasingly emasculating the players who are, and have always been, football’s most important asset.

Nothing emphasises this more than the constant and demeaning screaming at players to “stand” every time a mark is taken or a free kick awarded. It’s akin to ordering the naughty schoolboy to stand in the corner.

The “stand” rule is an unnecessary new rule that gives too much of an advantage to the attacking team. Worse, it gives the overzealous, predatory umpire any excuse to award a 50-metre penalty.

It goes without saying that we must obey the umpires and they must be respected but the AFL, by demanding we respect the umpires, is ignoring that most basic of life’s principles: “Respect has to be earned”. Besides, it’s an Australian characteristic to question authority. It’s embedded in our DNA. No authoritarian edicts will ever crush that.

As an aside, in discussion with the great Barrie Robran this week, he recalled a game between North Adelaide and West Torrens in 1972 umpired by Robin Bennett. A total of 105 free kicks were awarded. (59 to the Eagles, 46 to North). In last year’s AFL grand final three umpires awarded 35 frees. And now there are four?

However, it’s not only the slavish submission to the umpires that’s softening the game. Any show of aggression or discord is slowly being eliminated from the game.

In last week’s Showdown, young Crow Luke Pedlar, executed a perfect tackle on Port’s Dan Houston.

The momentum of the tackle and Houston’s attempt to spin out of it took both players to the ground. In another era it would probably have earned Pedlar a free kick. Instead, the umpire ruled it was a dangerous tackle and awarded a free kick to Houston, who was unhurt and jumped immediately to his feet.

The injustice of the free kick was a bad enough but Pedlar was later reported and suspended for one week by the match review officer who once again placed the Adelaide Football Club under disproportionate scrutiny.

Football fans can understand the AFL is trying to make the game safer, whether it be for altruistic reasons or simply to mitigate any future litigation by players who claim to have long-term injuries but there is a certain type of player who is being persecuted.

The football warrior who thrives on a superior desperation to win the ball at all costs is being umpired from the game. He’s the one on hands and knees scrambling desperately for that loose ball on the ground while the opponent takes the soft option by sweating off, holding the ball under him and raising the other hand to con a free kick from the umpire.

It’s football’s most frustrating interpretation. It’s bad enough the umpires no longer reward perfect tackles because of a nebulous “no prior opportunity” interpretation, but they can’t wait to penalise a player who wins a ground ball but can’t get it out of a mauling pack.

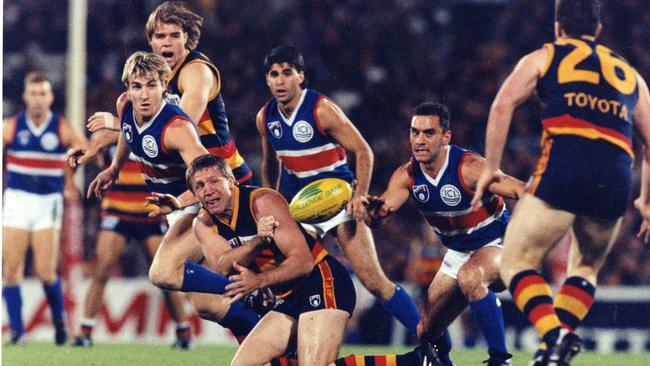

Inaugural Crows captain, Chris McDermott, arguably the state’s greatest in-and-under player, would have been umpired from the game if modern interpretations were applied.

The same goes for Tony Liberatore who won a Brownlow Medal for his in-and-under desperation. Players like Glenelg’s all-Australian defender Scott Salisbury who built a career on courage, desperation and the intent to win the ball against more talented opponents are now an endangered football species.

Yes, football had to change. To watch old footage is to understand why the game had to be made safer. Similarly, football recognised its obligation in society to stand against racism, violence against women and become more inclusive.

Traditional masculinity of the 20th century with its hidden flaws has morphed into a “healthy masculinity”. The fabric of today’s football reflects all of that – but it’s missing something. That boisterous, unquenchable, indomitable spirit of adventure, courage and defiance is slowly being extinguished. If only the lawmakers and the keepers of the game could recognise it.