FROM fighting diabetes with 3D printers, easing back pain with prawns to applying the tech behind Netflix to fight the flu, SA’s brightest brains are performing modern miracles.

“I mostly had people who were genuinely interested in donating their stool for a good cause, and a small fee,’’ says Dr Sam Costello, founder of Australia’s first public stool bank, Biomebank, at the Basil Hetzel Institute in Woodville.

“I did get the occasional prank text message or photo regarding a recent drop off at one of the university toilets that made me laugh. I suppose this is to be expected if you advertise for poo at a uni.”

This was followed, in the grand tradition of rookie gastroenterologists, by practising experimental techniques on his own stool, a trip to Finland where he watched a new and exciting procedure performed via colonoscopy, and a bit of trial and error back home with different processing and storage protocols.

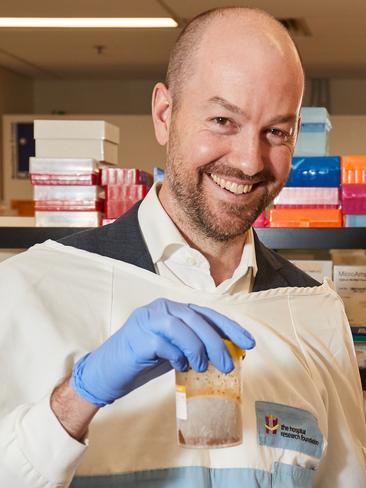

Now, armed with a blender, saline, glycerine, and donated poo, Dr Sam Costello is forging a path with a novel therapy that is already proven to be the best option when it comes to fighting the potentially deadly bowel infection Clostridium difficile — Fecal Microbiota Transplant.

In very layman’s terms, this means taking a healthy person’s poo, blending it, and putting it into a sick person’s gut. There, the healthy donor person’s gut bacteria is able to colonise the sick person’s and fight pathogens that may have taken over.

Usually found in those with compromised immune systems or after long courses of antibiotic treatment, C.diff infections can cause severe diarrhoea and dehydration, can lead to kidney failure and even death. A new strain has recently emerged that produces more toxins than other strains.

I often explain it as trying to replace ‘good bacteria’ into the gut and perhaps this helps decrease the ‘ick’ factor.

Stephanee Hermsen, 22, had a kidney transplant in 2016. After collapsing on the netball court when she was 16 it was discovered her kidneys were much smaller than they should be and a congenital problem meant urine was flowing backwards, destroying what function she had left.

Her mum, Sam, donated a kidney, and straight after the surgery Stephanee felt great even with the 10 tablets she takes every day to suppress her immune system to stop her body rejecting the organ.

Then the infections began.

“Eight months after surgery I started having tummy problems,’’ Stephanee says.

“I had three months of being really sick with C.diff — vomiting, feeling really sick, dehydration, diarrhoea more than 20 times a day. And the antibtioics to try to treat it made me so sick.”

Those antibiotics would work while she took them, but as soon as the course was over the C.diff would be back.

At the end of 2016, Dr Costello suggested a Fecal Microbiota Transplant.

Stephanee was the first kidney transplant patient in Australia to have one.

“The next day I was better,’’ she says.

“I’ve had no hospitalisations since. I’m as healthy as a transplant patient can be.”

FMT is usually suggested as a therapy when patients have had multiple releases of Clostridium difficile infection or have had very severe infection and have failed other therapies.

“Because this infection can be very debilitating most patients who are suffering with it are more concerned about getting better than the ‘ick’ factor,’’ Dr Costello says.

“I often explain it as trying to replace ‘good bacteria’ into the gut and perhaps this helps decrease the ‘ick’ factor. Also we usually deliver the FMT via colonoscopy and so a patient usually will be asleep when it is occurring and so this probably helps too.”

While FMT is recognised as the most effective treatment for recurrent C.diff infections with cure rates of 80-90 per cent of cases with most stool donors, it’s still not known exactly why it works.

A diverse gut bacteria colony is part of the answer — the more different types you have, the better — but is there a “super” bacteria? Do thin people have different bacteria to obese people? What else might be treated by stool transplant? And is there, in fact, a perfect poo?

Dr Costello is hoping to answer at least some of these questions.

“We still do not understand what components of stool are responsible for the effect (in treating C.diff),’’ he says.

“We know that people with C difficile often get the infection after taking antibiotics and that they have a reduced diversity of bacteria in their gut. Faecal transplant improves the diversity of bacteria in the gut and does often cure the disease however faecal suspensions with the live bacteria removed still seem to have some therapeutic effect so it may be that some components of the stool other than the bacteria are contributing to the effect. This is the focus of a lot of research at the moment.

“We believe that bacteria in the stool play a role however there are many other components of the stool — metabolites, viruses, fungi — that may play a role. Once this is better understood we may be able to select a ‘super donor’.”

And the potential applications of FMT reach further.

In addition to treating patients with Clostridium difficile infection and Ulcerative Colitis, the research team led by Dr Costello and Dr Rob Bryant are collaborating with Dr Hannah Wardill and colleagues across South Australian hospitals on a study where patients having chemotherapy save their own stool prior for re-administration into the bowel after their treatment.

They are also collaborating with Dr Lito Papanicolas and colleagues at SAHMRI and Flinders University on a study of faecal transplant as a treatment for patients with multi-drug resistant infections.

Finally, they will also be collaborating on a study with Dr Sam Fortser and other researchers in Australia in culturing bacteria from the bowels of people from the general population to get a deeper understanding of what bacteria occur in the gut of Australians.

Eating diet high in fruit and vegetables and other sources of fibre helps keep a healthy gut population.

“The aim of our research is to discover links between the gut microbiome (flora) and disease and also to determine whether we can improve disease by modifying the gut microbial environment,’’ he says.

“We have done this through faecal microbiota transplantation. We have shown along with a couple of other groups that FMT can induce remission of ulcerative colitis in about 30 per cent of cases and this opens up a potential new therapy for patients, however we do not know whether this therapy will be effective in the longer term and so more research needs to be done before it can be recommended.

“We have used anaerobic processing methods that have not been used in other trials in the past and our anaerobic facilities have been provided by the Hospital Research Foundation which is very important for us.

“Our long term aim is to accelerate the development of rationally designed microbial therapeutic products that can do the job of FMT in a more standardised way.”

This means studying stool, and this means more donations are needed.

“Prior to becoming a stool donor a person undergoes thorough screening,’’ Dr Costello says.

“This involves a medical questionnaire and examination to ensure that they do not have any active medical problems. They then have a blood test and stool test to screen for disease. We test for and exclude many infections as you would expect but we also exclude a range of other medical problems for example diabetes or obesity are exclusions. The stool itself is tested for infections. At this stage we do not analyse for the composition of beneficial bacteria although this is something that may happen in future.

“There are very few well-documented side effects from FMT. It is important to note that FMT has been performed in large numbers only in the last five years or so and so we therefore don’t have good long term safety data. So there is the risk of the unknown anytime a new therapy becomes available. There is a risk of transmission of infection which is low when donors are screened.

“There is also a theoretical risk of weight gain or obesity if an overweight individual donated stool. In animal studies it is possible to cause animals to gain weight through stool transplant and so we ensure that donors are a healthy weight.”

The knowledge gained from studying what comes out of us can also inform what we should be putting in.

“A diverse gut flora is associated with health and conversely lower diversity of gut organisms has been correlated with many diseases.

“There are some diseases where we think a lack of organisms in the gut directly contributes to the disease and there are others where there is an association and more research needs to be done before any causal link can be declared.

“The best time to establish a diverse gut flora is early in life particularly in the first three years. After this time a person’s gut flora is relatively stable. Breast feeding seems to be a critical factor in this regard. It is during this early period that the body’s immune system is deciding what to tolerate and what is foreign and to reject and so being exposed to the natural environment and picking up a diverse array of organisms as a young child is also likely to have long term benefits.

“Many beneficial gut bacteria require fibre and so eating diet high in fruit and vegetables and other sources of fibre helps keep a healthy gut population. Antibiotics either prescribed or in food can damage gut bacteria and so avoiding unnecessary antibiotic exposure is a good thing. Food additives such as preservatives and emulsifiers can also cause abnormalities in the gut bacterial populations. Exercise has also been shown to be beneficial.”

Prawn gel probe spawns hope for back pain breakthrough

EVER battled peeling a prawn and wondered what it is about the shell that makes it so annoying to remove? Adelaide researchers believe a part of the shell that makes it strong but bendy could help ease excruciating pain after back surgery.

Using Netflix, Uber tech to keep flu outbreaks in check

COULD ‘big data’ technology used by Netflix and Uber be the key to getting a grip over influenza outbreaks? A team of Adelaide-based researchers is finding out.