The Kangaroo Islanders: Little-known chapter of SA’s past brought back to life

Kidnap, castaways and a brutal life beyond the end of the world. This is the dark history of life on SA’s islands before Adelaide was born, brought back into the light.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When people think of the white settlement of South Australia they tend to think of 1836, William Light, Governor Hindmarsh and an Old Gum Tree.

However there’s an older, darker and perhaps more interesting chapter in the settlement of our great state. It’s one that took place in the years between Matthew Flinders’ mapping of our coast in 1802 and the official establishment of Adelaide 34 years later.

It’s the story of our offshore islands and the men who lived on them. Men who wanted to escape society, men who’d been used up by the European war machine and no longer saw a future in their own countries. Men who could be cruel and brutal, but were also brave and enterprising.

It’s the story of the women these men brought with them, indigenous women kidnapped from their ancestral homes in Tasmania, the Bass Strait islands and the Australian mainland and forced to live and work with these men in a role somewhere between slave and wife, relying on their wits and their deep connection with country to survive, and in some cases even thrive.

And it’s the story of our seals – New Zealand fur seals and Australian sea lions – that lived in their millions along our southern coastline and offshore islands.

It was these seals – brutally clubbed and skinned to make the boots and top hats of British gentlemen – that allowed this life beyond the pale to exist.

It was a life that went largely unrecorded, particularly in SA. There were no historians, journalists or artists on hand to document this unique lifestyle, and few written accounts, particularly in SA.

There was, however, a novel. Called The Kangaroo Islanders: A Story of South Australia Before Colonisation 1823, it was written by colonial author W.A. Cawthorne, the son of a lighthouse keeper who, through first-hand observation and stories from his father, had an unparalleled insight into the life of these isolated people.

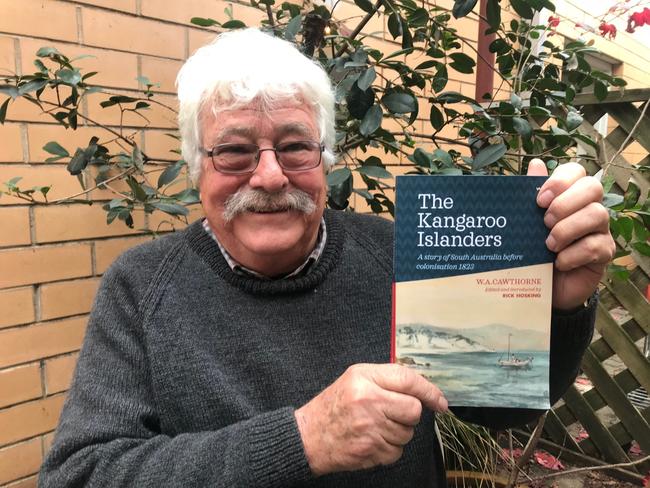

First released as a serialised offering in newspapers, and later as a complete work, it has been out of print for the best part of a century and has now been republished by Wakefield Press, with extensive notes and annotations from retired Adelaide academic Dr Rick Hosking.

READ MORE:

Drinks all round: Pubs reopen after Marshall booze backflip

MAPPED: Who owns Adelaide’s west end?

Now judgment looms for Marshall and Morrison

According to Dr Hosking, The Kangaroo Islanders is one of the most important, and overlooked, pieces of South Australian literature.

It tells the story of Captain George Meredith and his crew visiting the island to buy seal skins. Once there, they meet a motley crew of misfits, vagabonds and hermits they referred to as “Robinson Crusoe”, as well as the Aboriginal women these men had kidnapped as companions, including Maggerlede – also known as Big Sal or Bumblefoot – the tribal sister of famous Tasmanian Truganini.

Stolen from Bruny Island, Maggerlede is part of a group of Tasmanian and mainland Australian indigenous women forced to live in the “Robinson Crusoe” camps, working for the men killing seals and wallabies, which were also hunted for their skins.

Once on Kangaroo Island the sailors are astounded by the sealers’ rough lifestyle, the food they eat (echidnas, lizards and wild dogs are on the menu) and are shocked by the brutality of a kidnapping raid on the mainland.

Dr Hosking says The Kangaroo Islanders is significant for many reasons, one being that it shines a rare light on our early maritime history.

“This is a maritime history, and that’s a really important point,” he says.

“We kind of think about colonial Australia as being all about the bush and the inland, when in fact the coastline was far better known than the inland.

“And this is a novel about our very first export, which was seal skins. The skins themselves are fascinating – the British cracked the secret of how to treat the skins, and big industries started up in Calcutta. Most of our seal skins ended up there, where they were made into top hats and bowler hats. You can find bills of sale for tens of thousands of seal skins at a time.”

More than 1.5 million seals and sea lions were killed along the southern Australian coastline in the early 19th century, with numbers of fur seals only beginning to recover in recent years, and Australian sea lions remaining endangered.

The skins on Kangaroo Island were preserved with salt mined from two small lakes at the Bay of Shoals near what is now Kingscote, and the salt earned a reputation across Australia as being one of the best preserving salts in the country.

A half-wild horse was left on the island, caught and harnessed each time a ship needed to cart salt from the lake to the coast.

And it the novel is also important, Dr Hosking says, for its portrayal of the Aboriginal women who play such an important role.

“When I was first introduced to The Kangaroo Islanders I had been working on the history of representations of violence between whites and blacks in South Australia and I immediately recognised that this was an important book,” he says.

“And once I started reading it and realised that Truganini’s sister was in it I really knew it was something.”

Dr Hosking said many of the Aboriginal women outlived their captors and ended up successfully capitalising on their unique knowledge of both indigenous and non-indigenous skills.

“By the 1850s most of these women were living on their own, and they were living really interesting lives. They were trapping wallabies and selling the skins into Adelaide. Probably every colonial home had a blanket for wrapping babies in made of wallaby skins.

“This idea that they were all slaves and treated like animals, well there is lots of evidence for that. But on the other hand, what this book shows is these women working alongside whitefellas and teaching whitefellas how to hunt, how to kills seals. All the seal-killing information seems to come from Aboriginal people.

“There was no doubt though that these women were mistreated, but the women did have a certain freedom in that they could still practice their traditional behaviours and earn an income from the white community.”

While the novel may portray Captain Meredith and his crew as being surprised by the barbarity of the Islanders, history paints a different picture. The Captain was a famous abductor of Aboriginal women himself, taking people against their will at Point Nepean in Victoria and from Port Lincoln.

A report published in The Perth Gazette in 1835 and reproduced in Dr Hosking’s notes tells a tale of almost unfathomable brutality: “In November (1834), on Boston Island, the people of this latter boat caught five native women from the neighbourhood of Port Lincoln; they enticed two of their husbands into the boat, and carried them off to the island, where, in spite of remonstrance on the part of (James) Manning, they took the native men in Anderson’s boat round a point a short distance off, there they shot them and knocked their brains out with clubs.”

Cawthorne himself, however, had a far more enlightened attitude toward Aboriginal people, especially for the time. His watercolour paintings often depicted local people of the Adelaide region, and he even bestowed some of his children with Kaurna names (with one son – Charles Witto-Witto Cawthorne, going on to be a famous musician and musical educator).

“Cawthorne is a really interesting character,” Dr Hosking says.

“The poor bugger fancied himself as an artist, and in his diary he records sitting around for a whole Saturday waiting for people to come and buy his watercolours but nobody turned up.

“His famous pictures include the dugouts at the Burra Creek, and it’s one of the few representations we have of this, the Burra mine, Kangaroo Island and Yankalilla … lots of important things.

“He had a great desire to be a gentleman, and part of being a gentleman in the 19th century was to paint and to write and to study the sciences. He takes lessons, and befriends George French Angus, who copies a number of Cawthorne’s paintings. Cawthorne tried to be like Angas, but Queen Victoria came to see Angas’s paintings and Cawthorne never sold a single one.

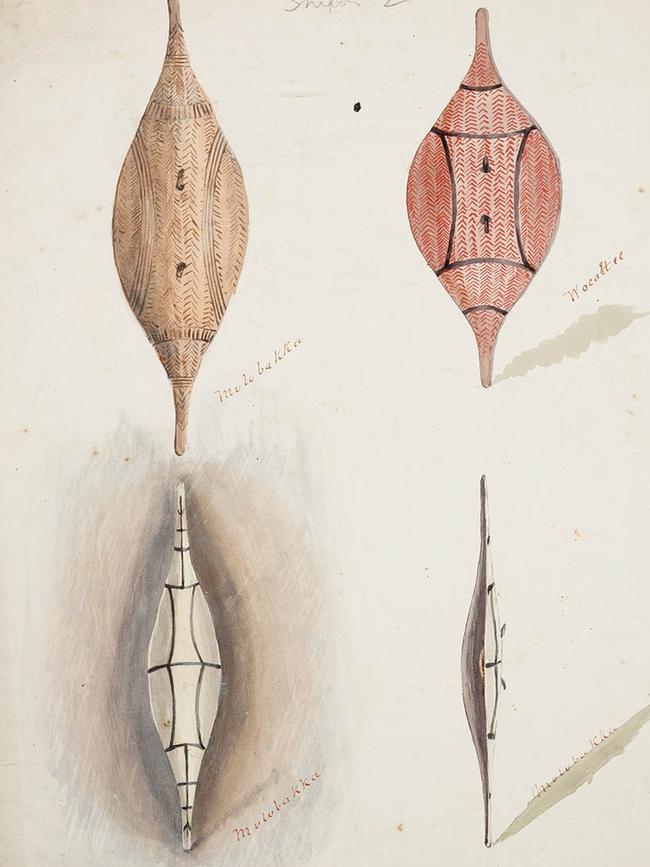

“Cawthorne’s scientific pride and joy was his paintings of the shields and spears, and the knowledge we now have of shield decorations and the like are down to him.”

Most of the Cawthorne family ended up in Sydney, and one of his daughters bequeathing his watercolours to the Mitchell Library, where they’re stored to this day.

“That’s one of the reasons why he’s not better known here,” Dr Hosking says.

“It’s a bit sad really.”

The Kangaroo Islanders: A Story of South Australia Before Colonisation 1823, by W.A. Cawthorne (edited and introduced by Rick Hosking) is available now through Wakefield Press for $39.99