South Australia’s bloody amazing medicine … from the benchtop to bedside

In a pretty ordinary building on Frome Rd, in between the Adelaide Zoo and Rundle St, there’s a blood cancer revolution going on — and our scientists are at the helm of some extraordinary medicine.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Cancer Atlas: Map shows how suburbs compare for cancer rates

- UniSA research on leukaemia drug wins GSK support

- Cancer Council SA teaming up in screening campaign

- SAHMRI funding for $2.5m hi-tech cancer therapy facility

In a pretty ordinary building on Frome Rd, in between the Adelaide Zoo and Rundle St, there’s a blood cancer revolution going on.

Blood cancer cells are being “popped” and DNA “splatted”.

Super computers are analysing up to six billion data points per cell to match gene mutations with possible drug treatments.

Extraordinary things are taking shape.

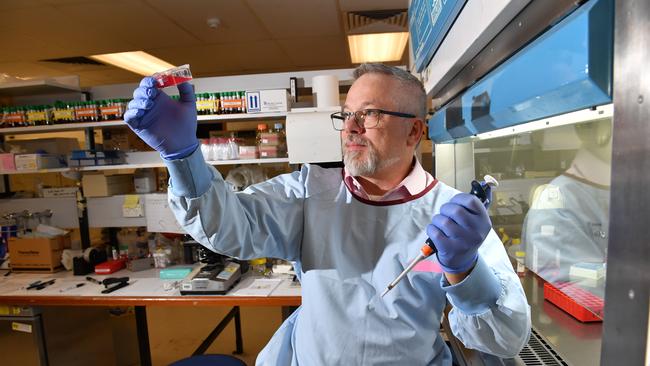

“What is being done here with blood cancer is not being done anywhere else in the world,” says Professor Hamish Scott.

“The process is revolutionary.”

He heads the department of genetics and molecular pathology at the Centre for Cancer Biology — an SA Pathology and UniSA partnership that belongs to the multidisciplinary health alliance, SA Genomics.

In coming months, SA Genomics will be one of two Australian research epicentres trialling the use of genomic medicines in blood cancer for the first time following a $1.8 million commitment from the Leukaemia Foundation and Tour De Cure.

Adelaide scientists will aim to match a patient’s individual genetic information with drug therapies, prevention and screening methods.

The trial will expand the Australian Genomics Cancer Medicine Program lead by Sydney’s Garvan Institute, which is using genomics on rare, advanced solid tumours with high mortality, such as sarcomas.

If successful, the trial involving SA Genomics and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane could give blood cancer patients access to emerging therapies up to 10 years faster — saving hundreds and hundreds of Australian lives, some at the end of their treatment options.

These emerging therapies are often not listed under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme nor publicly subsidised via the Medical Benefits Scheme.

“We want to be able to find targeted treatment options; better treatment options and treatment options that patients don’t or can’t normally access,” Prof Scott says.

It’s not the first time Adelaide has led the pack in blood cancer research.

Since the 1980s, Adelaide has trained world-leading scientists and researchers developing new and better ways to treat leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma.

SA researchers have developed tests to detect drug-resistant cancers, introduced new blood cancer drugs as part of clinical trials, developed cellular therapies, and discovered and tested for some hereditary blood cancers.

“If you had to be diagnosed with a type of cancer in South Australia, blood cancer would be the one as we have been leaders in this field for a long time,” Prof Scott says.

Blood cancer is a complex group of diseases linked to the production of blood in bone marrow and can be subdivided into three main groups: leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma. Each of these main groups can be further divided into more than 110 subtypes.

There are currently up to 14,000 Australians diagnosed with blood cancers each year, with recent analysis showing the number could jump to 17,000 by 2025, according to the Leukaemia Foundation. The peak body for blood cancer says that as Australians live longer, more and more will be affected by more forms of the disease, impacting not only the patients, but their families, work colleagues and the wider community.

Leukaemia Foundation chief executive officer Bill Petch says blood cancer will become an increasingly significant health problem in Australia — a fact now being realised by both major political parties as they head for the polls next weekend.

Labor has announced a $20 million commitment to give Australian blood cancer patients faster access to leading clinical trial drugs and therapies through a new Right to Trial program.

Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt has vowed to establish a Blood Cancer Taskforce and Action Plan to improve blood cancer survival rates if re-elected. Mr Petch says precision medicine — like that about to be the trialled for blood cancers in SA — can locate unique genetic mutations and match those mutations with the best treatment options as opposed to the traditional one-size fits all approach.

He says this would give blood cancer patients fairer and faster access to lifesaving therapies in the trial process that are safe for humans — a move that can currently take several years.

Patients, he says, that could otherwise be left with few or no treatment options after the failure of more traditional therapies.

He says that currently just one in five people living with blood cancer can access a trial — and that’s usually through the TGA’s Special Access Scheme or the compassionate access schemes of pharmaceuticals.

“Less than 30 per cent of blood cancer patients can access genetic testing to better inform their diagnosis and treatment,” Mr Petch says.

“This trial could, however, provide a systematic use and evaluation of off-label drug treatments that could be extended to a raft of other diseases.

“It could change the way we diagnose and treat disease and how we bring drugs to market.”

Adelaide couple Peter and Debbie Owens have spent the past year appealing to family, friends and anyone who’ll listen for much-needed dollars into blood cancer research.

They’ve raised more than $60,000 so far in the name of their son, Michael.

“Any advancement in the way blood cancer is detected and treated is critical,” Mr Owens says.

Michael died five days after he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) in April last year.

He was 23.

“It is a terrible disease and it can move fast,” Mr Owens says. Each year in Australia, around 900 people are diagnosed with AML. While it is rare, it can develop rapidly and without warning.

The causes of AML remain largely unknown but it is thought to result from damage to the genes that control blood cell development.

Mr Owens says more needs to be done to provide a genetic test for the disease to predict risk and prevent cases like his son’s.

“We never even had a chance to say goodbye — we don’t want another family to go through that,” he says.

There is currently no cure for blood cancer.