Rare insight from Japanese WWII diary translated into English

A new book has been released chronicling the experiences of a Japanese POW during World War II who was held in a fetid internment camp in South Australia.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

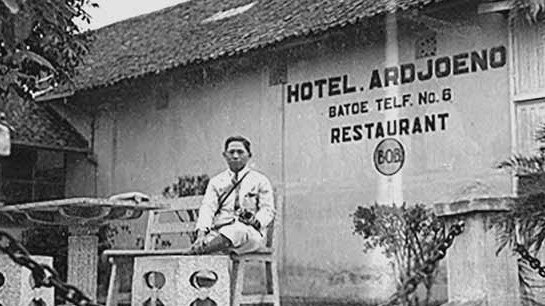

Miyakatsu Koike was working quietly in a Java branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank when his life was suddenly turned upside down in December 1941.

The Japanese national was arrested by Dutch colonial authorities based in Indonesia in the fallout of his country’s unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbour, in Hawaii, during World War II.

Mr Koike, then 36, had no military connections but found himself classified as a security threat and sent on a “hellish voyage” to an internment camp in country South Australia.

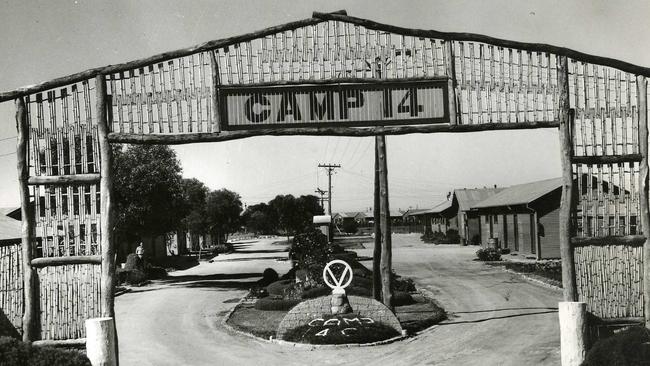

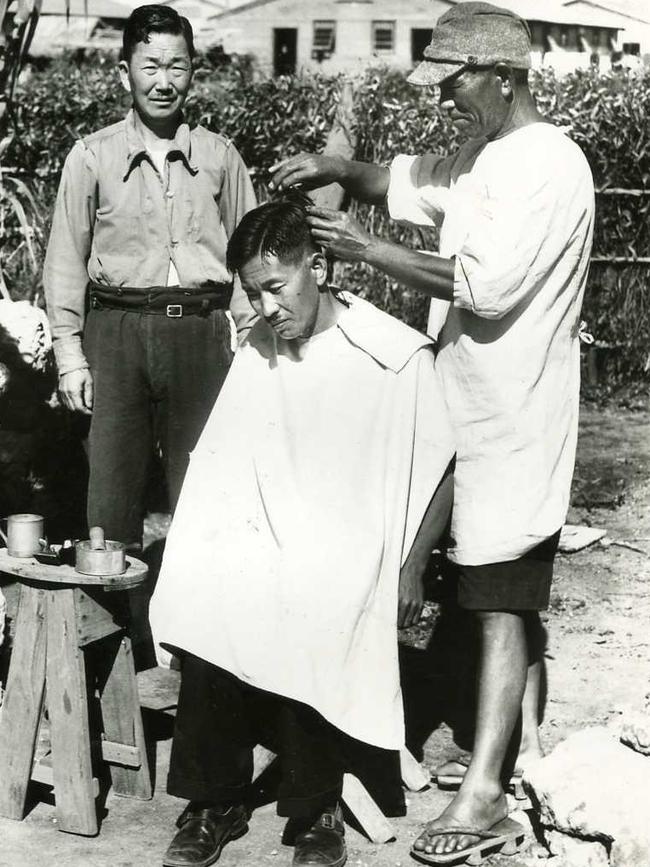

Loveday, near Barmera in the Riverland, grew to become the largest civilian internment camp in Australia, with more than 5000 internees and 1500 guards at its peak.

During his time in the camp, Mr Koike kept a daily diary about his struggles, recording the harsh conditions, his brutal treatment and his personal growth despite the hardship.

He finally returned to his home country on the Australian repatriation ship the Koei maru in February 1946, never to return to Australia.

Despite the rare insight into a crucial – and often unknown – part of SA history, his diary has long been inaccessible to most Australians.

It was published in Japanese in 1987 and now – 62 years after he was detained in Java – it has been translated into English in a new Wakefield Press book called Four Years in a Red Coat: The Loveday Internment Camp Diary of Miyakatsu Koike.

It tells a moving tale of the ordeal suffered by Mr Koike. His was yet another life destroyed at a young age by the war.

“Four Years in a Red Coat (the colour of camp uniforms) is a keenly observed record of this man’s arrest, his hellish voyage to distant SA, his endurance of years in the Loveday Internment Camp, and his return ultimately to a war-ravaged homeland,” says Professor Peter Monteath, of Flinders University, who coedited the book.

“The book is a testament to one man’s calmly stoic triumph over sustained adversity. The scars of his war are indelible, yet Koike emerges from it with his humanity not just intact but enhanced.”

Most poignantly, the diary spells out the tragedies that confronted Mr Koike when he was finally allowed to return home in March 1946.

“I heard from my wife that my father had died while I was interned,’’ he wrote.

“Both my wife’s parents and three of my uncles had also died.

“I also heard that my first son, who was due to be born in March 1942, had died a week after birth.

The diary will be an uncomfortable insight for many into how Australians of the time were viewed from the outside.

“Almost 11 years had passed since I left Japan in May 1935. I was, indeed, an unfilial son, who had returned home not knowing of my own father’s death.

“The train was heading due west in the darkness. On the way, I was pleased to see Mt Fuji, as beautiful as ever, greeting me, a poor repatriated person.”

Although not a well-known part of Australia’s past, the internment of non-combatants locally and from overseas as security threats was commonplace, says Professor Monteath.

Prisoners of war were also kept at Loveday, although for very brief periods and not at the same time as the civilians.

“The Australian government swiftly interned people who were regarded as security threats because they came from countries with which Australia was at war, with the largest groups being Italians, Germans, and the Japanese,” Professor Monteath says.

Parts of it capture how harshly Australian authorities treated “enemy aliens” at a time when Australia was directly under threat.

On the hellish sea voyage to Australia in a Dutch vessel, in which the main threat was the Japanese fleet, Mr Koike wrote: “I stayed in Surabaya (in Java) until the last moment in the hope that I could do something for the Japanese empire, even though my ability was limited.”

Disease was a constant threat on the voyage.

“We could not clean the toilet and its stench filled the whole ship,” he wrote.

“On top of that, most people were unable to have a proper bath for so long that an odd smell permeated the hold. It seemed as if we were living through hell.”

Professor Monteath says Loveday’s conditions were austere and regimented, much like in POW camps.

“Not only were the guards at Loveday and other civilian internment camps drawn from the Australian Military Forces, but the facilities were very similar to those of POW camps,” he said.

“Among Japanese internees in particular, release was extremely rare, and repatriation could not finally be arranged until well after the war had ended.

“Bitter memories of internment lived on in most internees for decades.

“It even lives on in their descendants to this day.”

During his time at Loveday, Mr Koike heard of the tragic 1944 breakout of soldiers from the Cowra POW camp, in NSW.

“On 5 August, a rebellion by Japanese prisoners of war in Australia occurred,” he wrote in his diary. “Two hundred and thirty one people died and 18 huts were burnt down. One hundred and eight people were wounded”.

But small details in the diary will reassure readers that there was still humanity for the enemy, even with the backdrop of bitter fighting to the north.

Mr Koike wrote this description of an excursion from the camp for the funeral of one of the 134 Japanese who died at Loveday: “While I was fascinated by the beautiful scenery of the vast continent, suddenly a car stopped, and an old foreign gentleman got out of the car.

“The gentleman took off his hat and silently paid respect to the deceased. Humanity has no boundaries.

“I was greatly moved by this Australian gentleman’s warm heart.”

The diary’s end records the heartbreak and chaos Mr Koike discovered when he returned home.

But it is clear his internment never broke his spirit. And he was able to marvel at Australia’s empty beauty. “From the train, we could see vast undulating grazing land,’’ he wrote as he was finally journeying home.

“I saw no herd of cattle or flock of sheep, but only eucalyptus trees here and there. Once again, I marvelled at the vast Australian continent.”