SA Weekend: Former Japanese prisoner of war camp at Loveday in South Australia’s Riverland has gone to rack and ruin

The ex-Japanese prisoners of war in Cowra NSW has been restored as a tourism attraction and place for spiritual reflection. Yet Australia’s largest holding centre for incarcerated civilians – at Loveday – has been allowed to rot, writes Nigel Starck.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The former camp for Japanese prisoners of war at Cowra in NSW has been lavishly restored as a tourism attraction and a place for spiritual reflection. Yet Australia’s largest holding centre for incarcerated civilians – at Loveday, near Barmera – has been allowed to rot.

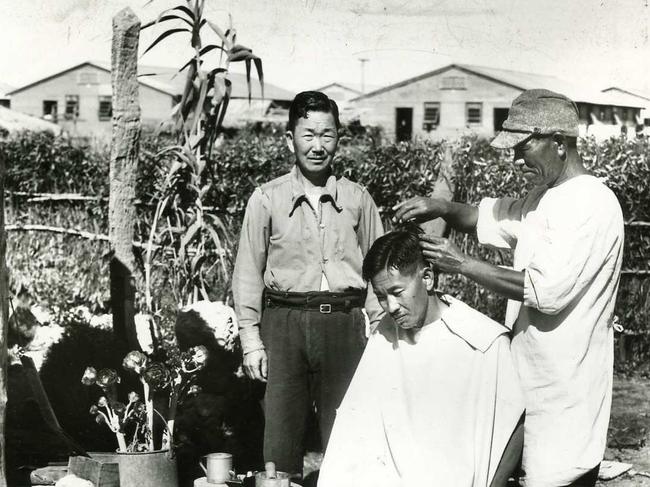

The remnants of rural South Australia’s major World War II enterprise lie neglected on the region’s rich riparian plains. These relics of an exercise in productive imprisonment have suffered decades of looting and neglect.

Today, the surviving element of Loveday Internment Camp – which held, at its 1943 peak, 5382 inmates – appears as a mongrel landscape of rust, rubble and skeletal buildings.

Loveday, though, does have a small coterie of articulate advocates championing its possible rescue, and it possesses an extraordinary story to tell.

Slowing down to let a pair of kangaroos lope across a Barmera backroad, I had spotted a weatherworn brown sign telling me I was alongside the site of ‘Internment Camp No 9’. That sign, though unimpressive in itself, would point the way to a trek of memorable discovery.

There were 18 such numbered wartime stockades right across the nation. Loveday, founded in 1940 and named after the pioneering irrigation engineer Ernest Loveday, became the setting for Camps 9, 10, and 14.

It took its first reluctant guests the following year, as part of the Allied powers’ crackdown on so-called ‘enemy aliens’ – people, for the most part, of German, Italian and Japanese heritage. The number held in Australia would grow to more than 15,000.

In his book Captured Lives, Flinders University historian Peter Monteath says many were established Australian residents who simply “found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, and paid a heavy price”.

Fingers of accusation were pointed at some on the flimsiest of suspicions; they would encounter a Kafkaesque trial of fear, hate and undeserved retribution.

Others, says Monteath, were shipped here in a new wave of transportation – from the UK, Palestine, Iran, the Straits Settlements, New Guinea and the Pacific islands. Such ocean passages could be perilous, threatened by submarine attack, as a shipload of internees and prisoners of war bound for Canada from Britain found out. Their vessel, the SS Arandora Star, was torpedoed by a German U-boat; 613 died.

Professor Monteath’s book recounts the story of Michael Glas, born in 1896 in what was then Austria-Hungary, who had been living in the UK. He survived the Arandora Star sinking, only to next be marched aboard the notorious troopship Dunera and sent to Loveday, while his wife, Alice, was interned on the Isle of Man.

The Dunera voyage proved to be a shameful episode in Britain’s conduct of the war. Although most of the passengers were Jewish refugees, and therefore passionately anti-Nazi, they were subjected to persistent abuse. Human waste flowed across the deck; guards threw possessions and documents overboard, smashed beer bottles and forced their charges to walk barefoot over the glass.

The one measure of good fortune for the men of Loveday – it was an all-male detention centre – can be found in its commandant, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Dean. A decorated World War I artillery veteran, he proved to be a visionary in the art of governing a multinational workforce.

For, by agreement, most inmates did respond to his encouragement that they should work – and be paid a shilling a day – to make Loveday self-sufficient, healthy, innovative and profitable. In his peacetime calling, Dean was an Angaston grazier; a man with a profound knowledge of crop production and animal husbandry.

The official history of the camp, held at the State Library of SA, recalls his record of “vision and enterprise”. Loveday, sprawling over 179 hectares 6km southwest of Barmera, produced vast quantities of agricultural seed; raised pigs and poultry; grew vegetables in abundance; and supported the war effort further still through its prolific woodcutting camps outside the wire.

And then there were its opium poppy harvests, supplying in the year 1944 alone more than half the Australian military’s need for morphine.

Much of the territory has now gone to orchards, vineyards and solar farms. But the corner of Loveday that was once defined as its headquarters precinct lies unkempt and unloved, an accretion of barbed wire, old truck parts and broken masonry.

That wasteland saddens National Trust member John Beech, whose father developed a post-war soldier settler block on the camp site. “It’s a disgrace,” he says. “I’m disgusted that bit’s been allowed to deteriorate to such a condition.”

Rosemary Gower, who organises tours of the site through the Barmera Information Centre, shares his pain.

“It desperately needs to be cleaned up because it’s an important part of our war history,” she says, pointing to such Loveday characters as:

PRINCE Alfonso Del Drago, a nobleman who had migrated to Sydney in the 1920s, unwisely telling the press that Mussolini was “a very wonderful man”.

FRANCESCO Fantin, an Italian anarchist, slain – possibly with a rock – by another inmate, subsequently given a two-year sentence for his manslaughter.

GUS Bunaguro, a tailor from Adelaide whose fiancée, Gwen Thompson, travelled up to the camp so they could be married by the Catholic chaplain. She was then automatically classified as an alien herself and had to obtain a pass to go back home.

At Flinders University, Monteath also believes the remnants of Loveday are worth saving. “The old headquarters area has a lot to offer in the way of remaining buildings, albeit dilapidated,” he says. “There’s still some potential there.”

He maintains that the sector containing the former cell block, pay office and recreation hall – about two football ovals in size – could be transformed into an interpretative centre. It would require building renovation, fencing, a car park and explanatory display boards, along with an app for visitors’ smartphones.

This, he says, has worked at Cowra. It could work, now, at Loveday.

The centenary of Barmera, in 2021, would be a good time to start – if Australia’s latest mass internment is over by then.