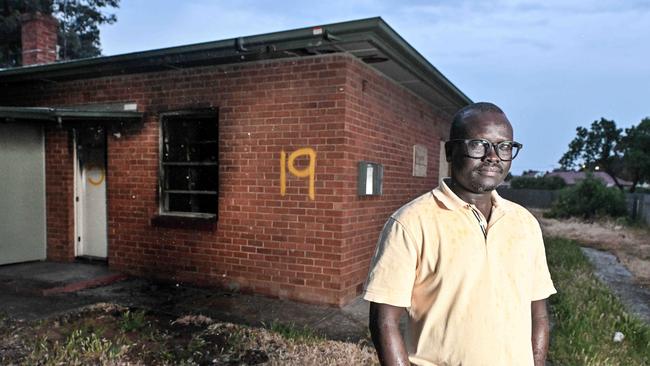

Is this Adelaide’s scariest street? Former child soldier in South Sudan, Mr Bol Bol tells of life on Nelson St, Kilburn

Parents won’t let their kids play outside for fear of stepping on a syringe or being hit by a rogue bullet. Welcome to Adelaide’s street of horror.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A former child soldier in South Sudan, Mr Bol Bol knows what it is like to live in a war zone – and be forced to fight in one.

He had to battle his way to a better life in South Australia via a period as a teenager sleeping rough on the mean streets of one of the world’s most dangerous cities, Johannesburg in South Africa.

Now he lives in Nelson St, Kilburn, in Adelaide’s inner north, where disturbingly he sees some parallels.

“It’s almost like a war zone here too,” he says.

The Sunday Mail spent a night guided by Mr Bol Bol, who did not want his first name published, along arguably Adelaide’s scariest street – which could also fairly be dubbed our street of shame due to the level of official neglect it has suffered.

The reporter slept outside on the porch of an abandoned Housing Trust home as rain bucketed down and lightning flashed across the sky.

The lightning bolts were the only thing that illuminated the dark street, which is fragrant with eucalypt despite being on the fringe of a factory district.

The Housing Trust-dominated road has been known as one of the toughest spots in Adelaide for decades. But it is only getting worse due to a string of violent incidents.

In January, a family home was peppered with bullets in a drive-by shooting which put a 17-year-old boy in hospital.

That house has since been boarded up and abandoned. So too the unit next door – a familiar sight on the 150m-long strip.

Fifteen other houses are boarded up or have smashed windows.

Some are near completely burnt out – the fire brigade now uses the street for training.

That’s the second thing you notice when you arrive. The first is the number of large vacant blocks from the dozens of houses already bulldozed years ago, but not replaced.

On September 29, another home was targeted by a group of 10-15 machete-wielding people.

At the time, a 13-year-old boy there said he believed the armed group were members of a gang called KBS who were after his 16-year-old brother because he was friends with people from a rival gang – but not a gang member himself. There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing by any of the occupants, who have since moved out. Neighbours say nobody lives there now.

On Friday, detectives from youth gang-focused Operation Meld arrested a 16-year-old boy from Salisbury North. He was charged with serious criminal trespass and property damage over the incident.

When Mr Bol Bol, 42, heard the flurry of gunfire in January, he knew exactly what it was.

“I know what a gun sounds like,” he says.

As a 10-year-old boy he was separated from his family because of constant aerial bombing. Then his father was shot dead on the front line and he was forced to become a child soldier for the South Sudan Liberation Movement.

After seeing people die right next to him, he fled the country aged 15, lived on the broken concrete streets of Johannesburg and eventually made it on a humanitarian visa to Australia, where he found work “doing jobs that every other Australian would refuse to do”.

He is grateful for his life here but despairs at conditions on the street and lack of action to make things better.

“I can look after myself,” he says. “But we have people stealing our shoes when we leave them outside. How did they become so desperate?”

He wants the government to act – more street lights, speed bumps to stop hoons and programs to help youths find their way in a “society where you still need to work extra hard” as migrants, with so many having suffered immense trauma in their former countries.

He says he has asked the Housing Trust why it demolished the homes and whether his house, where he lives with a wife and four children, will be next – but has received no firm answers.

It’s not just Mr Bol Bol who despairs.

Elizabeth, 29, who has lived here in public housing since she was a child, has watched many houses be trashed and then condemned, attracting squatters, looters, regular IV drug users and joy-riders torching stolen cars.

“We don’t let our kids play out the front because there are always needles around,” she says.

The mum of two is pregnant and is desperately trying to get a transfer out of her two-bedroom home. She believes some of the houses, which have up to six bedrooms, should have been refitted rather than abandoned, and says the Housing Trust won’t tell her why an existing house cannot be refurbished for her to move in.

Further down the street Melissa, 36, slowly opens the door to her public housing unit with her shy old dog wagging its tail behind her.

She recalls a night a man nobody had seen before, sweating from a meth injection, came along with a large knife and wooden pole, going from car to car slashing tyres.

Melissa then points to the sky as the rain comes down. “Can you see that? We have no street lights in our cul-de-sac and only three on a 150-metre street”.

In a statement, SA Housing Trust did not answer questions about why the houses had been demolished rather than refurbished or what the vacant blocks would be used for.

“Sixteen properties on Nelson St, Kilburn have recently been approved for demolition as they are no longer fit for purpose,” she said.

There are more than 15,500 people on Adelaide’s public housing waitlist while 1450 public housing properties are vacant while maintenance is undertaken.

SA Housing Minister Nick Campion said his government were “increasing the number of public houses in the state” for “the first time in a generation.”

“Kilburn is scheduled for upgrade in the near future with plans already underway for its renewal.