Connor never imagined himself becoming a drug addict – then he tried ice

Connor never imagined himself becoming a drug addict. He had a happy childhood, passed year 12, got into uni. Here’s how he fell into a life of ice and crime – and how he’s fighting his way out of the darkness.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Connor remembers the first time he tried ice. He was 18. He always told himself he would stay away from the drug. Not that getting high was a problem for him. He had been a regular marijuana smoker since he was 13 and was also taking the anti-anxiety medication Xanax.

Sitting in front of a log fire at the Tumbelin Farm rehab centre in the Adelaide Hills, Connor says he was “adamant’’ he would stay away from ice. “It would never be me.’’

But then a mate told him to give it a try.

“That one question. Do you want to try it? I thought about it and I think that addict mind thought, like ‘fuck it, why not, let’s do it’’.

It was a decision that almost killed him. Ice led him down a path of overdoses and suicide attempts. Of crime and being arrested. Of thinking there was no hope. Of trying to quit drugs but falling back into old habits. He describes a miserable life.

“You never see yourself turning into a junkie,’’ Connor says. “You don’t see that happening to yourself. Growing up I never thought I would turn into a drug addict, but that’s just what happened.”

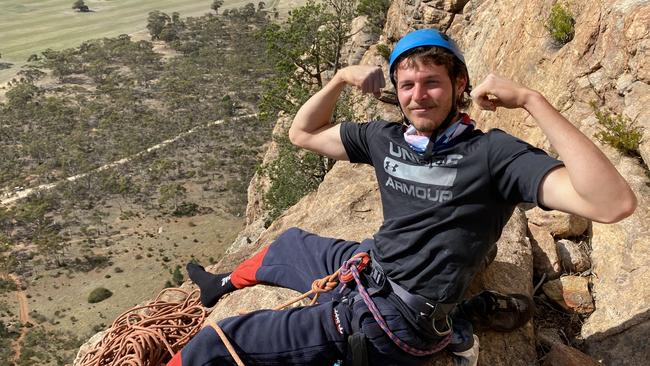

Connor is now 22. He has been clean for six months, his longest time off drugs since he was 13. He looks healthy now. Daily gym workouts and martial arts and a job in a warehouse have put back on muscle and weight and altered his junkie skin-and-bones frame. He speaks directly about his life, even though it’s clearly difficult for him. He pauses to collect himself before answering some questions. Occasionally, there is a sheen in his eyes.

But he is talking because he wants other addicts to know that there is a life outside drugs. Not an easy life, but a good life, a fulfilling life.

Connor says he had a happy childhood, although something of a troublemaker, describing himself as a “class clown’’. But he says he always had trouble fitting in and finding friends, especially when he went to a high school in Adelaide’s western suburbs.

His father worked in the construction industry, while his mother was a nurse. The marriage ended when Connor was 12 and he says his “acting out’’ worsened after that. He fell in with a group of boys and had that “first bong’’. He became a regular user. Several times a week became a daily occurrence before school. He noticed his friendship group had whittled down to just one other mate. For year 12, he decided to move schools.

A bad break-up with his girlfriend led him to find Xanax on the street. He stayed clean while in the relationship but when it ended he resorted to old habits.

He started going into the city and found a new bunch of mates. He started selling marijuana to support his own habit. Despite it all he passed year 12 and was accepted into uni to study teaching. Instead, he deferred for what was going to be a year.

It was around this time that the ice question was posed. Connor says when he’s on drugs “I just cannot moderate, I just go too hard’’. After a month he stopped. Life was just too “hectic’’.

But he had the taste. And he liked it.

“Taking it, I would feel in control of everything,’’ he says. “You almost feel like you could stop a car coming at you. I just felt so confident and strong.’’

The mate who introduced him to ice had an uncle who was 39 and also a user. Connor moved in with them. He was paying no rent but there was a price to pay.

“I just pretty much had to go out and do petty crime with them,’’ he says. “We would call it going on missions. These guys have obviously been doing ice for years. It’s their life, they don’t know a different way and they’re looking at me like I can make them some money.’’

Connor knew the life was damaging him. He came to understand that he was being manipulated by older men. But he was stuck.

“I just stopped caring about myself. I did not matter in my life. It was getting high that mattered and having a good time.’’

He tried to leave it behind. He smoked himself into psychosis and ended in hospital where he was given anti-depressant and anti-psychotic medications which didn’t work.

“I just knew the whole time what was happening. There’s no illusion anymore. I’m either going to kill myself or overdose.’’

He tried a 12-step program. He started to cut off his old mates. Deleted their numbers, deleted his social media, changed his phone number, moved home with his mum who continued to support him. He would get clean for a few months, then relapse. Get clean and fall again.

He would even go back to that house.

But by the end of last year he had been clean for five months. Then went on a two-day bender. But this time on alcohol. When he sobered up, he took himself to hospital feeling suicidal.

“I didn’t feel like they took me seriously. They kind of sent me away and told me to take meds,’’ he remembers.

“I decided I was going to try and take my life. I got in my car and baited the cops into a high-speed chase. I thought I’d try and get the cops to kill me or I’ll crash and maybe I’ll die.’’

It almost worked. Connor says he was driving at 200km/h around Adelaide before he crashed. He was sober but “just having a mental breakdown’’.

He survived but ended up in hospital for a month. He came out and relapsed one more time. Again on alcohol.

But this time he knew his time was up. He restarted his 12-step program and found Tumbelin Farm when he started researching rehab places. Tumbelin Farm sits between Mt Barker and Macclesfield. It’s a working farm with 30 cows and the young men work it four days a week. One day a week is dedicated to “adventure therapy’’ such as rock climbing, abseiling or hiking. There are also counselling services.

Tumbelin Farm is run by Baptist Care SA and is funded by the Federal health department until mid-2024. It can take four young men at a time but would like to double the intake and expand to take in young women as well.

Clients join the farm after undergoing detox and can stay for up to six months.

Tobin Hanna is manager of adventure pathways at Baptist Care SA and says while there is no such thing as a “typical client’’, many young people start taking drugs to start “coping’’ with other issues such as mental health challenges.

“They’re not bad people, they’ve generally made poor choices under difficult circumstances, and now they want to make better ones,’’ Hanna says. He says the program’s focus on outdoor life helps both physically and mentally.

“Young people typically come here guarded and on-edge – unsure how this is going to go,’’ the former high school teacher says. “For some young people it has been years since they’ve eaten or slept properly, so some of the simple rhythms of farm life can make a big difference.’’

That feeling of being outdoors and useful changed Connor’s life.

“That kind of reminded me there is a world out there,’’ he says. “When you spend so long doing drugs around the same people, in the same shit house, that’s what your world becomes. This dark place. It’s almost like a nightmare when I look back on it. It’s just this gritty dark place with no love, nothing good. No sunshine.’’

Getting out in nature is now his “medication’’. “I’ve just got to remember to do it and I’ll stay sane’’.

Not that it’s easy. Fitting back into ‘normal’ society is a challenge for any addict. After the chaos of his old life, his new life can be a little “mundane’’. He has a job which helps give him routine but is looking to work in mental health and to help other addicts.

Connor is six months clean but knows his addiction is not beaten. That the addiction is “still doing push-ups in the back of my mind’’.

It’s why he still says he can’t afford to look too far forward.

“Every now and then when she gets tough, my head wants to go back,’’ he says. “That’s because the old life, I understand it, I know it. I know if I go back into that, at least I know what’s going to happen. I’m probably going to die. But at least I’ll know that. Right now, this is uncharted territory.’’

But there’s a determination to Connor. He wants to do it for his mum and dad who didn’t give up on him. He wants to show other addicts that escape is possible.

“There is another way. There are people who do care, you don’t got to go through this. There is a life out there and you do deserve it.’’