‘The Boy in the Machine’: How Odinn 2.0 saved lonely schoolboy

Just 40 children in Queensland have the same rare disease as Odinn Meehan. And the nightmare started with just a bout of Covid and a few mild symptoms.

Pop into the aptly named Class 3D at Rainworth State School and it looks like any other bright and engaging classroom. Colourful drawings, motivational quotes, keen little faces.

Today the children are learning persuasive writing and their teacher, Katrina Hammond, is asking them to read the adopt-a-pet section of a mock newspaper.

Now things get a little atypical. Hammond places a copy of the paper on a corner desk at the back and suggests eight-year-old Odinn Meehan moves from the front of the class to the desk to have a read. So off he goes.

Or, more accurately, off rolls Odinn 2.0.

Odinn is a sick boy, struck by a rare arthritic-like auto-immune disease, juvenile dermatomyositis, or JDM.

Going to school is fraught. But not with the help of his classroom proxy, Odinn 2.0, a telepresence robot sporting wheels at the bottom, a skinny pole with a midriff bump for a body and a tablet-like screen as its head.

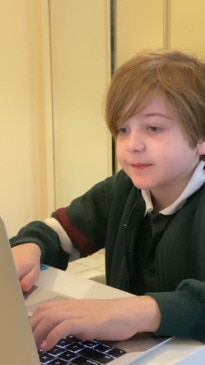

Beaming out from that screen is Odinn’s happy face.

He’s at home, in Bardon, in Brisbane’s inner west, dressed proudly in his school uniform.

Using his laptop controls, he turns the robot and with the wide camera view of Odinn 2.0 as his guide, negotiates it through the space between his classmates’ desks.

Some of Odinn’s friends wave as the robot passes by, then, as if a robot in their midst is as natural as breathing, these tech-savvy kids get back to reading.

Odinn 2.0 makes it to the desk and Odinn presses buttons to lower the tablet, like a head on a hinge, to look at the work. As if he was right there in the classroom.

Ever since March last year, when Odinn began to show the symptoms of JDM after a bout of Covid-19, the ensuing battery of diagnostic tests, treatment, stints in hospital, and the risk – and reality – of more Covid infections, conspired to keep him at home.

Away from his mates. And it was getting him down.

“Odinn’s default setting is joy, he’s a happy kid, a very optimistic kid and he loves school,” says his mother, Romy Willing, 47.

“For a very social and empathetic child, to lose that connection with his friends, I could see that after a time there was a shadow that came over him. He was lonely.”

Rainworth did what schools do, sending out study sheets for his mum to work through with Odinn, and welcoming him on the days he made it to class.

When he was receiving treatment at the Queensland Children’s Hospital, its school staff guided him through lessons.

He was learning but it was not the same as being in class to see Johnny’s new haircut, hear Mary’s poem or watch Hammond write maths equations on the board.

That’s where the not-for-profit MissingSchool initiative came in. Willing and her husband, Damien Meehan, 48, had not heard of the innovative program until a QCH School teacher mentioned it.

“We talked about the fact that Odinn wasn’t in hospital for big enough chunks for him to be regularly at the hospital school but he wasn’t able to go back to school, so he was sort of in this in between space,” Willing says.

“And that’s where MissingSchool is amazing.”

It began 11 years ago, when three determined mothers sat together in a Canberra living room, mothers whose children were on a long road of intensive medical treatment to save their lives.

They were incredibly grateful for that but as the days and months dragged on, as the kids’ worlds grew smaller, the mothers could see a shift in their children. A loneliness, a sadness, a disengagement.

Says Megan Gilmour, one of those mothers and now CEO of MissingSchool: “It’s not just about saving bodies, it’s about saving hearts and minds as well.”

Since 2017, MissingSchool has been rolling out telepresence robots to schools across Australia, connecting seriously ill kids with their normal classroom.

It’s now received a federal grant and private sector funding worth $800,000 for a pilot program, Seen&Heard, to help schools tap into other technology already at their fingertips in a bid to keep these digital natives switched on and connected to their school when they’re too sick to attend regularly.

To Odinn and Willing, the robot has been a game-changer. No longer is Willing mother and teacher. She’s Mum. “When a child is going through a challenge like this, they need their parents to be a safe haven and for me not to have to do the homeschooling relieves that stress and means I can be Mum, that safe haven,” Willing says.

And for Odinn? “I can hear and see people and I can answer questions,” he says. “It’s just cool.”

A RARE DISEASE

The registrar at QCH considered the symptoms Odinn was displaying – fever, tiredness, weight loss, a light red rash on his face and elbows “like he’d grazed himself”, sore legs and swelling around his ankles.

As chance would have it, the registrar was training in rheumatology. “I think,” he said, “it might be this very rare disease called juvenile dermatomyositis.”

Instantly, Willing knew what that was. “And I said, ‘It can’t be that’.”

Willing is an arts administrator, not a doctor, but those words had been part of the broader Meehan family’s lexicon for a decade.

“I said, ‘I know how incredibly rare it is and his cousin has it and it’s generally not a familial disease’.”

All that is true – the number of new diagnoses of JDM per year is about two to three in a million globally, and, says rheumatologist Dr Rebecca James, the lead on Odinn’s care team, it is “extremely unlikely, almost unheard of, to have two family members with the condition”. Roughly 40 children have JDM in Queensland.

But when all the tests were done, that’s what Odinn had. Just like his cousin, Jude Meehan.

Jude, now 14, developed it when he was four.

His father Lachlan Meehan, 56, says Jude’s case followed a bout of giardiasis, fuelled by a waterborne parasite that causes diarrhoea, nausea and stomach cramps.

The family came down with it after moving into a rental property after their home was hit by the 2011 floods. The rental had not been used for some time and it’s believed the giardia parasite was in the pipes.

Everyone got better, except Jude, who started to get a rash, straw-like marks under his cuticles and limb pain.

In Odinn’s case, Willing says the symptoms started after his first, relatively mild bout of Covid in January last year, and his first Covid vaccination the following month.

“It takes either a severe sunburn or a big immune response to trigger JDM,” Willing says. “He’s had whooping cough and other illnesses over the years but none of them trigger that big immune response and Covid is the only thing that could be pointed to as a possibility. It’s not definitive but it seems fairly obvious.

“And of course, Covid is such an unknown.”

James says a conclusive cause is uncertain but what’s happening to Odinn’s body is clear.

“Fundamentally, this condition is about an overactive immune system,” she says. “Normally the job of the immune system is to attack viruses, germs, bugs and bacteria but in Odinn’s case his immune system is attacking his own body, in his muscle, his lungs.”

Odinn has MDA5 JDM. The MDA5 antibody can affect internal organs and tests showed Odinn has interstitial lung disease.

As a result, he receives low doses of cyclophosphamide – a drug traditionally used in higher doses as chemotherapy – to suppress his overactive immune system.

He’s also on steroids, which make his face puffy, and intravenous immunoglobin, which he had a bad reaction to early on before adjustments were made.

And that’s the seesaw Odinn is still on, with medicines and delivery methods being tweaked until his condition is stable.

“We’re still trying to balance the immune system and that can be a really tricky and protracted process,” James says.

It can take two years to hit that sweet spot but with Odinn’s immune system suppressed, he’s susceptible to viruses.

He’s had Covid twice since the first case, setting his treatment back.

Viruses and the danger of Odinn overextending himself make going to school risky. He tried at the start of the year, says Willing, revelling in being back with his mates. By the third week, he had a seizure. But Odinn 2.0 was waiting.

The robot he first used in September last year is a link, a bridge, to the normal, everyday world he’s so eager to rejoin.

There are many more Odinn’s out there. Good data is lacking but MissingSchool (which is lobbying for more specific absentee terminology) has crunched available figures to find about 1.2 million Australian children, or 30 per cent of students, face a physical or mental illness that puts them at risk of missing school.

More than 70,000 children miss months or years of schooling due to a serious physical illness. Kids with enough challenge in their lives, without adding the burden of isolation, loneliness and falling behind at school.

Gilmour watched what that burden did to her son Darcy. He was 10 when he was fast-tracked for a bone-marrow transplant, after being diagnosed with three rare blood disorders, the last of which was pre-leukaemia.

That was in 2010 but the memory of those terrible, frightening years doesn’t fade. Her voice wavers over the phone line.

“He got worse after the transplant, he just became more and more unwell,” she recalls. “All of the medical treatments that were happening to save Darcy’s life were also the very things that were causing a lot of pain, trauma and injury to him and everything he had been fighting for had disappeared. It was gone. So, what was he fighting for?”

He saw less of his friends, surrounded instead by adults, many of them poking and prodding him. He couldn’t go to school, couldn’t be a kid.

By the 18-month mark of his ordeal, Gilmour could see a marked changed in Darcy. “He was giving up. He was depressed, he was traumatised. It was just pain, so much pain.”

That, says Gilmour, is when she started to ramp up her lobbying, her fight for sick children to get as close to being at school as possible. Darcy’s school was good in many ways, she says, but it had a blind spot when it came to using technology to bridge the gap.

“I did meet a lot of resistance and was seen as difficult,” says Gilmour, who has since received a range of awards for her advocacy, including being a finalist for 2018 ACT Australian of the Year.

“But all the things that have crossed my life that I’ve been criticised for – you’re stubborn, you’re too outspoken, you get too focused on things – turned out to be strengths that enabled me to do this.

“I’m okay with not needing to be liked because my focus is not on anyone but the kids. Part of this is about changing the status quo. The status quo is comfortable.”

By 2015, MissingSchool launched Australia’s first report on the challenges facing kids who miss school because of serious illness or injury. Then, it started rolling out robots, with more than 180 now in schools nationally, reconnecting about 5400 classmates.

“I’m so grateful for those obstacles, the fuel for seeing things a different way, because it enabled us to do what we’ve done and really put this issue on to the national agenda.”

In an odd way, the pandemic helped. It elevated teleconferencing from “nice to have” to a vital communication tool.

Suddenly, everyone was using Zoom and Skype and schools were coming to grips with latent technology. For the benefit of all kids, healthy and sick.

It makes no sense, says Gilmour, that those devices, that connection, has been largely switched off in schools as society moves to living with Covid.

Once again, sick kids have been unplugged. If anything, given the risks of Covid to vulnerable children, teleconferencing should be supercharged in schools.

Which is what Seen&Heard is about. It’s a big ask to get an $8000 robot into each of the 9500 schools in Australia. But every school has some form of tech.

Monitors, newfangled touch screens on an A-frame, a TV on a trolley – what does a school have that could be adapted to bring a sick kid into the classroom? Identify it, and Seen&Heard will help make it work.

Because, says Gilmour, schools must. Federal education regulations governing them, and the access they offer, say so.

This “absolutely, categorical” fact became clear to Gilmour at the start of the pandemic, in 2020, when she sat down to write a paper as part of her policy impact fellowship with the Churchill Trust.

She wanted every school to accept that it was a child’s right to be at school, if not physically, then virtually.

But it seemed a mammoth task. “Eight states and territories with three major education systems to change,” she says. “Impossible is what I said to myself.”

She started reading. Gilmour once managed and directed aid and development projects for agencies such as AUSAID, the World Bank, United Nations, the Asian Development Bank. She’s worked in government, trawled reports, written funding bids. She has an eye for detail.

Her “golden moment” came when she landed upon the Disability Standards for Education, regulations under the Disability Discrimination Act. Illness is included as a “protected attribute”.

“It’s undeniable that it applies,” she says.

“All of its language covers all the circumstances MissingSchool talks about: it specifies access to the classroom, learning alongside peers, access to the curriculum, provision of assistive devices to provide equal opportunity. Those things are exactly what’s needed here.

“It was like I found the key to the door,” Gilmour says. “We turn that key now and it has been profound what we have been able to do.”

And now, it’s doing more. MissingSchool has broadened its focus from physically ill kids to include those with mental health conditions.

The number of children deeply reluctant to go to school, known as “school refusal” or “school can’t”, has been growing since Covid, so much so that a federal parliamentary inquiry is being held into the issue.

Gilmour gave evidence, arguing that we have the capacity, and obligation, to help those kids now. She also pointed out that not helping children at the crunch-time of their illness and schooling will prove more costly: a Victoria University study showed that incomplete education leads to a lifetime lost productivity cost of nearly $1 million per student.

“There was a time,” she told the inquiry, “when we didn’t provide access via wheelchair ramps in schools. We see technology … as the on-ramp to provide access to the classroom in the circumstance where that student can’t physically attend.”

She told the inquiry about Owen, a year nine student with autism and anxiety who missed more than a year of school following Covid. Then he got a robot.

“It has changed him,” said Owen’s mother, quoted in Gilmour’s submission. “He jumps up, ready to get on the robot … he interacts with teachers and peers continually and is a lot happier.”

It’s stories like these that keep Gilmour pushing for the 21st century educational rights of sick kids. She has a wish. Not the big one, the one where Darcy grows into a healthy adult. That came true and he’s now a “very fit young man” of 22.

Her new big wish is that the Seen&Heard pilot program leads to more funding, so that by 2025, every school has the technology it needs to keep kids connected to their schools as they go through a health crisis. Then this stubborn, outspoken, ultra-focused mother can move on.

ME AND MY ROBOT

It’s just before school starts and Odinn heads outside, walking slightly pigeon-toed due to JDM’s impact on his thigh muscles and hip flexors.

He settles on a daybed on the deck to discuss an extra-curricular project he’s working on. It’s about why all sick kids should have a robot to do school.

“Because,” he says earnestly, “some kids feel lonely and sad and don’t have anyone to play with or do anything and a robot would help because they get to see their friends, and they get to do maths.”

Was he lonely sometimes? He nods. “I was.”

Until Odinn 2.0. His mum says Odinn was nervous the first time he beamed into the classroom. Not about manoeuvring the robot – that was easy.

But he was aware he looks different because of the steroids and “he was worried, ‘Have they forgotten me; will people treat me differently?’.”

With some trepidation, he clicked on the link to the robot. “And the kids just went bonkers,” Willing says. “They were so excited to see him, they just thought it was fantastic. That took all his fears away.”

It’s less of a novelty now, just part of the class, although Hammond did have to coach the students to restrict saying hello to Odinn to the start of a lesson.

The only extra load Odinn 2.0 has put on her teaching is turning it on. “Odinn’s amazing with it, how he moves it around, and every now and again, I’ll say, ‘Odinn, what did you write?’ or he asks me questions.”

Rainworth State School principal Lee Martin shows some subject matter to Odinn Meehan via the telepresence robot. Picture: David Kelly

The robot’s ease of use has been an eye-opener for the school’s principal, Lee Martin. She’d recommend it to any school. The connection it provides is vital.

“It’s just so important for Odinn but also his friends – kids are very empathetic and they have that connection back with Odinn. He’s here, through the robot.”

Over little lunch at Rainworth, some of his eight-year-old schoolmates talk about learning with Odinn and the robot in Class 3D. It is, they say, “cool” to have such tech in the school, and for Odinn to have the same lessons as them.

“He can still learn and he can still feel connected with the class,” says Stella Bartholdy. “It’s fun waving at him,” says Charlie Moule. All of them understand that being at home so much would get a bit lonely.

Millie O’Connor tells how fun it is when Odinn 2.0 joins them outside for lunch and they can hang out with Odinn. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, she says, “we have some crazy, funny chats”.

It’s good having the robot, says James Moloney, so they can talk to Odinn, wave to him. But he also likes it when Odinn comes to school to pick up some books or study sheets. “Yeah,” Millie concurs, “then we can see him in real life.”

Bit by bit, Odinn the Original will return.

The day will come when his disease has stabilised, his medication is sorted, and he heads through the school gates, eager to complete his schooling. In real life.

He will know his classmates and their little quirks, be up with his lessons and slip back into a routine many kids take for granted. And Odinn 2.0 will have done its job, free to roll off and be that bridge for another sick kid.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘The Boy in the Machine’: How Odinn 2.0 saved lonely schoolboy