It was the Everest trip of a lifetime – and then Covid came along | Paul Ashenden

We were on the trek of our lives to the Mount Everest base camp when we suddenly became headlines in the biggest story on earth, writes Paul Ashenden.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

We were on our way down a Himalayan mountain when we heard the news.

The Foreign Affairs and Trade Department (DFAT) had issued an edict advising all Australians abroad to make their way home as soon as possible.

It was early March, 2020 and countries around the globe were closing borders as cases of Covid-19 skyrocketed.

The world had changed considerably since we had flown out of Sydney, bound for Kathmandu just over a couple of weeks earlier.

When we had left, there were just two cases in Australia. Sure, China was in lockdown and things weren’t looking great in some parts of Europe, but nothing we had read led us to believe the world would be turned upside down so quickly.

In retrospect, maybe it wasn’t the wisest decision to go ahead. OK, it definitely was not – but we had been planning and training for this trip to Everest Base Camp for nearly two years.

We were one of the last groups of internationals allowed into Nepal before it shut its borders and were lucky enough to be allowed to hike to base camp, via Gokyo Lakes and the Cho La Pass.

The hike exceeded our expectations. We were there in early March, the very start of the trekking season and the snow-covered peaks and tracks were straight out of a travel magazine.

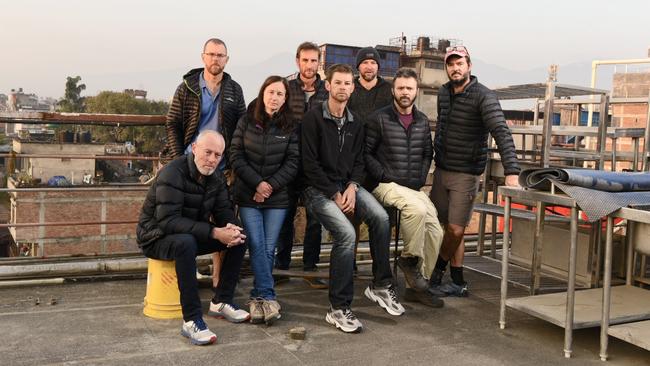

Our group of eight only had one major altitude sickness scare but, despite initial fears we’d need to call in a rescue chopper, we had started our trek down from base camp (altitude 5364m), when DFAT issued the edict for all Aussies abroad to come home.

Internet access in the tea houses of the Himalayas was consistent and we had been following the spread of the pandemic each night. So that DFAT direction was hardly a surprise, but it did snap us into action and we doubled our pace in an effort to get down off the mountain and back to Kathmandu as soon as possible.

Our route home was via a small plane from one of the world’s most treacherous airports at Lukla (Google it – it’s pretty amazing). We rang ahead, changed flights and hiked into Lukla a day earlier than planned but, alas, the weather gods were not on our side.

Unrelenting cloud and snow meant our plane was delayed by 24 hours – a setback which would prove critical in our efforts to get back to Australia.

By the time we arrived back in Kathmandu, our Malaysian Airlines flights home had been cancelled. We made a beeline to the Malaysian Airlines offices, only to find them closed, then went to the Australian Embassy – also closed.

And so it was back to our prearranged accommodation, where we spent the next few days searching for flights online amid frantic calls to worried families back home. We thought we were onto a winner after buying tickets on an Emirates flight in a couple of days’ time. Less than 24 hours before departure though, it too was cancelled.

A couple of trusty spouses working the airline websites back home then booked us on a Qatar flight.

And then, about 8pm on the night we were due to leave, word filtered through Nepal had been ordered into a strict nationwide lockdown. From 6am the following morning, martial law would be enacted to keep people off the streets.

Some reports suggested Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan International Airport was closed for both incoming and outgoing planes, but no one seemed to know for sure.

So we had another tough decision to make.

Head to the airport before the 6am curfew in the hope it was still operating and we could get on our flight, or stay at our accommodation in a city where hotels, restaurants and, well, everything, were gradually closing down.

We opted to head to the airport and arrived about 5am to find it closed. We sat, dismayed, with our bags under a shelter at the entrance, plum out of ideas.

To make matters worse, I had acquired a nasty dose of Bali belly in the previous 12 hours. Being unwell in a country on edge about an impending pandemic was less than ideal, but I huddled in the foetal position near my bag as my healthier travelling companions watched incredulously as gun-wielding police and army personnel moved in to enforce the martial law.

It soon became clear they wanted us off the street – which was problematic, because we had neither transport nor accommodation. So they herded us into the carpark of the abandoned airport. Chaos reigned supreme. Once in the carpark, the instructions changed, and we were told to return to the streets, with our luggage.

That’s when a white knight in the form of the Australian ambassador’s wife came to our rescue. Literally. Her name was Emma Stone and she’d been following our plight from some of the pictures we had been posting on a Facebook page we had created called Australians Stranded in Nepal.

As we were being moved from pillar to post, she reached out and told us to stay put – the government plates on her four-wheel-drive meant she could drive through the roadblocks and come and save us.

The relief when we read her message was surpassed only when she arrived, picked us up and took us to her home – the Australian embassy – and enjoyed the best vegemite on toast any of us had ever tasted.

Emma and her husband, then ambassador Pete Budd, worked tirelessly over the next few days to charter a Nepal Airlines flight home for more than 200 Aussies stuck in Nepal. It was a historic journey – the first direct flight between the two countries and we touched down in Brisbane on April 1 to a vastly different Australia we had left a month earlier.

Before returning to Adelaide we were required to spend two weeks in hotel isolation in Brisbane. We booked flights home to Adelaide but, of course, those flights were cancelled within days, so when we left isolation our only way home was via hire car.

We completed the drive in 21 hours, stopping only for food and petrol. Once we arrived back in our homes, we had yet another two weeks of home-based isolation before we were finally able to return to society. By that stage, it was nearly two months since we had left on a hiking holiday which was supposed to last three weeks.