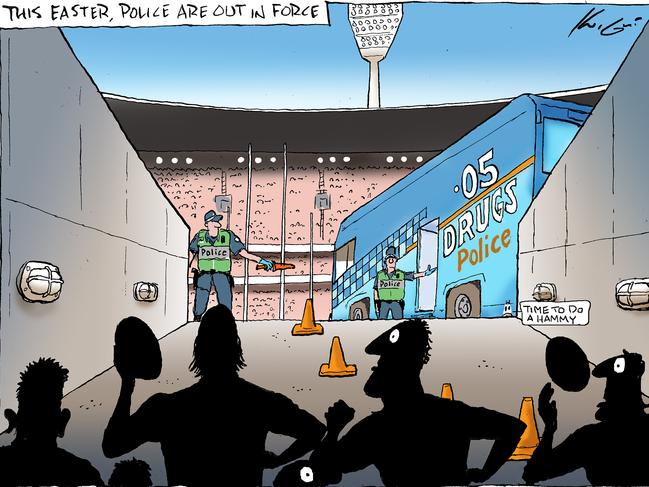

AFL players are subjected to more rigorous scrutiny and control than most other Australian athletes | Graham Cornes

Back in Graham Cornes’ day, some players would sneak a few pints of beer after training. But the world has changed ... Cornesy analyses whether the AFL’s drug policy is working.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

This is an old but true football story. Two teammates (who shall remain nameless) were caught by their coach drinking at the local pub on a Friday night before a game. The coach didn’t say anything until the next training session when he commanded them to run 20 laps as punishment.

After the 10th lap, one of them, a most colourful character, gasped: “For ****’s sake coach, we were drinking beer, not petrol.”

Oh, for those simple days when the most toxic substance a footballer could ingest was beer. And it wasn’t illegal to do so.

Federal MP Andrew Wilkie is not the first politician to attempt to use footballers to enhance his profile or reputation. Remember those Labor ministers, Kate Lundy and Jason Clare, who presented the Australian Crime Commission’s report on the use of banned performance-enhancing drugs and a criminal element in sport?

Eleven years later and that infamous press conference, “the darkest day in Australian sport”, is revealed more as a political stunt than a serious concern for the integrity of professional Australian sports people.

The scapegoats were those unfortunate 34 Essendon footballers who were railroaded into a year’s suspension. None of them had tested positive for a banned substance and the relatively benign substance they were eventually suspended for taking was not on any banned WADA list at the time. But that was then.

Under parliamentary privilege this week, Wilkie read a prepared speech saying that he had a signed statement from a former, disaffected Melbourne Football Club doctor that some Melbourne footballers were faking injury because they had tested positive to a banned substance in “off-the-books” and “secret” testing.

It is sensational stuff and has guaranteed Wilkie unprecedented publicity. But far from uncovering any nefarious practices, the revelations are simply a distortion of the AFL’s Illicit Drug Policy, which has been implemented in addition to the universal World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA) code.

The two are often confused by the those who are wont to criticise the AFL. The criticism that the AFL’s policy attracts is often because it doesn’t seek to punish the players but to rehabilitate them.

In the wake of this week’s controversy the AFL Doctor’s Association president, Dr Barry Rigby, was compelled to issue a clarifying statement. “The AFL Illicit Drug Policy (IDP) is based on a medical model and provides a structure of supportive care for the player. It is not meant to be punitive and over the years has been based on trust and confidentiality between the player and the doctor……[it] aims to deter use while providing avenues for education and treatment.”

My biggest criticism of the AFL’s policy has always been that it offers too much protection to the player who abuses the concessions that they are given. Most significantly, when it was first introduced, the player was not named, nor was he immediately suspended. Only the club doctor knew who he was.

It was (and remains) a silent pact between the doctor and the player. Neither the coach, the club chief executive or the head of football knew. A player being traded out and, more importantly, a player being traded in could conceal his history of drug use.

The league’s medicos and the AFL Players Association countered by saying that confidentiality was vital to rehabilitation. It has been revised since its initial introduction but the player is still not named after his first strike.

However, while he receives a $5000 fine, which is suspended, he then enters a target testing program. If he tests positive a second time, he is publicly named and suspended for four matches. If he is stupid enough to test positive a third time, he is suspended for 12 months.

Some say, and I agree, that a third strike should warrant a suspension for life. AFL players occupy a privileged, highly paid position in society and with that privilege comes responsibility. You don’t deserve that privilege – and an average wage of over $400,000 – if you don’t have the discipline to abstain.

The other contentious issue around the AFL’s IDP is that a player can self-report his drug use and avoid penalty if he enters a controlled treatment regimen.

But what should we make of the former Melbourne doctor’s revelations that so excited Andrew Wilkie, a man incidentally for which I have the utmost admiration? It appears that the Melbourne Football Club and Dr Zeeshan Arain parted company in acrimonious circumstances which resulted in claims of unfair dismissal. It would be fair to say he was upset by his treatment.

Similarly, former president of the club, Glen Bartlett, is in the midst of a long-running battle of disaffection with the club. His criticisms of the club chief executive Gary Pert, coach Simon Goodwin and captain Max Gawn, which began in April 2021 when it appeared he had been forced from the club, were silenced when the team won the premiership later that year. Yet they still persist, as do his seemingly vexatious threats of legal action.

The most disappointing thing about Wilkie’s leaking of Dr Arain’s affidavit was the revelation that the confidentiality that should exist between a doctor and his patient has been breached. Dr Arain may not have mentioned specific players by name but he has betrayed them nevertheless.

Then there is the distortion of the AFL’s IDP. These are not clandestine tests at some secret laboratory as suggested by Andrew Wilkie. They are the standard or targeted tests conducted under that program. Such tests are conducted at many work places, the big difference being that a positive test in a workplace normally results in instant dismissal. AFL players enter a controlled treatment program and only their doctor knows their identity until a second strike.

So how do you tell the world a player has to miss a game because the AFL’s independent policy has found him out? The football world is outraged that a player and his club doctor may have faked an injury. However, to give the real reason would be a more serious breach of trust between doctor and player.

Rival codes and other sports have ridiculed the AFL over these revelations but they ignore the fact that they don’t subject their participants to any extra testing. The AFL players are subjected to two different systems of detection; other sports only apply the WADA code conducted by Sports Integrity Australia.

AFL chief executive Andrew Dillon and Dr Rigby have not blinked. They have fiercely defended the league’s program. “We’ve got the hair tests done under the Illicit Drugs Policy, then we’ve got the clinical intervention model which is conducted by the doctors,” Dillon said. “If there’s a chance they might have a substance in their system – we don’t want them training, and we don’t want them taking part in matches for their health and welfare, above anything else.”

Critics of the AFL won’t be appeased and fans will now be suspicious of any player missing because of a minor injury but they miss the point. Those AFL players are subjected to more rigorous scrutiny and control than most other Australian athletes.

Sigh! It was much easier when their only transgression was having a few beers on a Friday night.