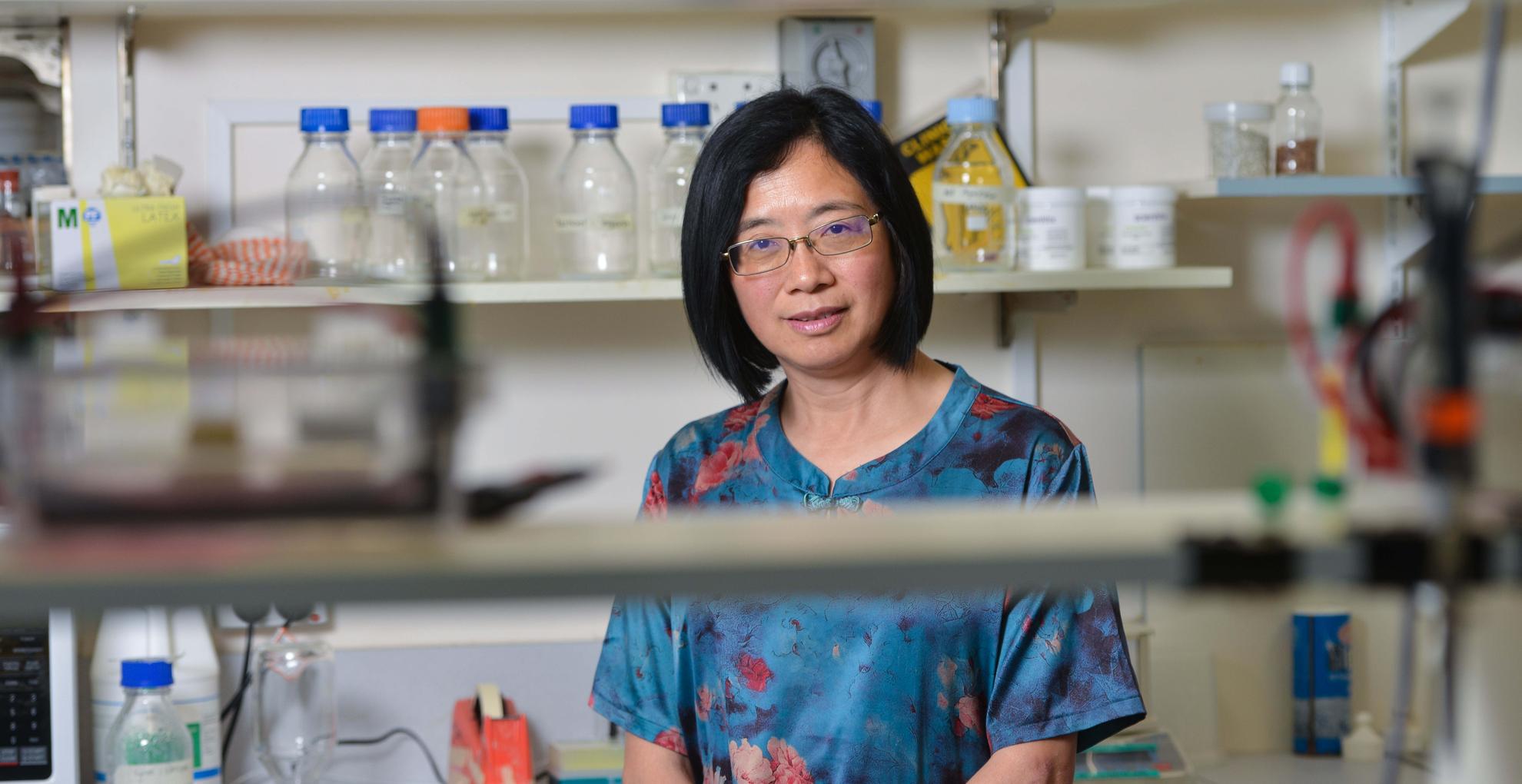

Dr Sui Yu grew up amid the terror of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, which took her mother and father from her. Now she has a successful career as Australia’s first genetic pathologist, three sons and a free life in Adelaide.

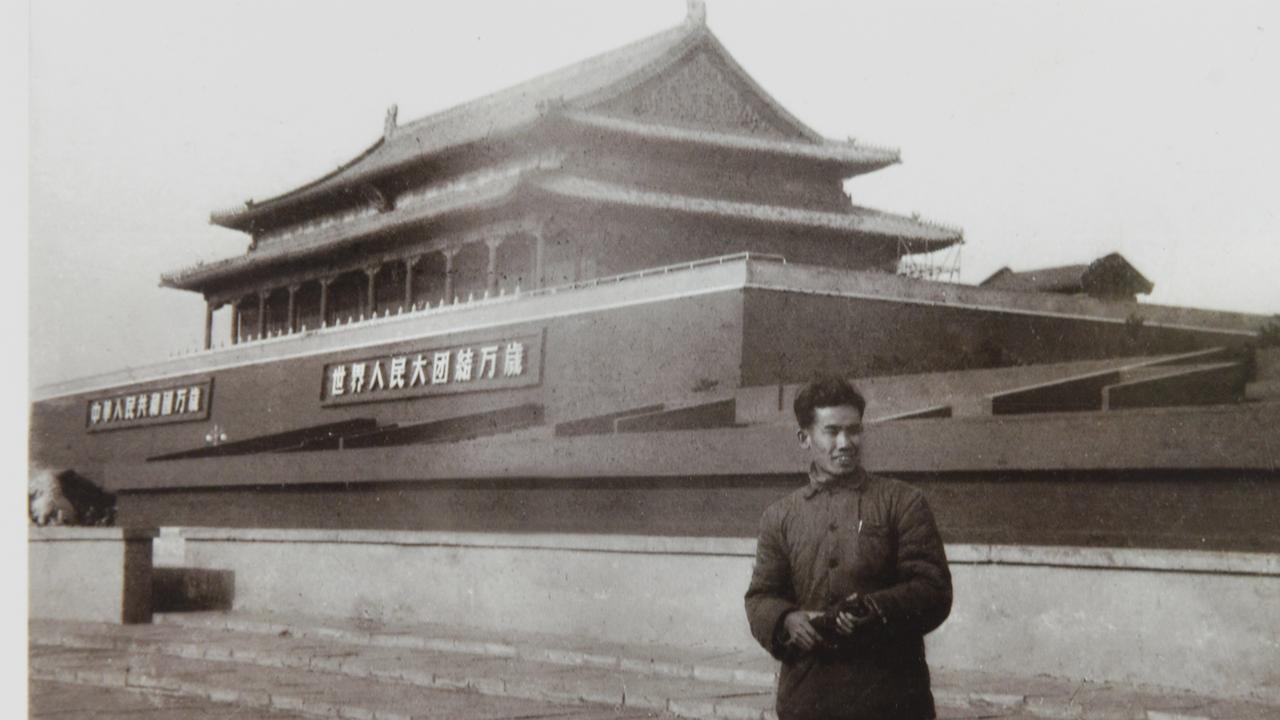

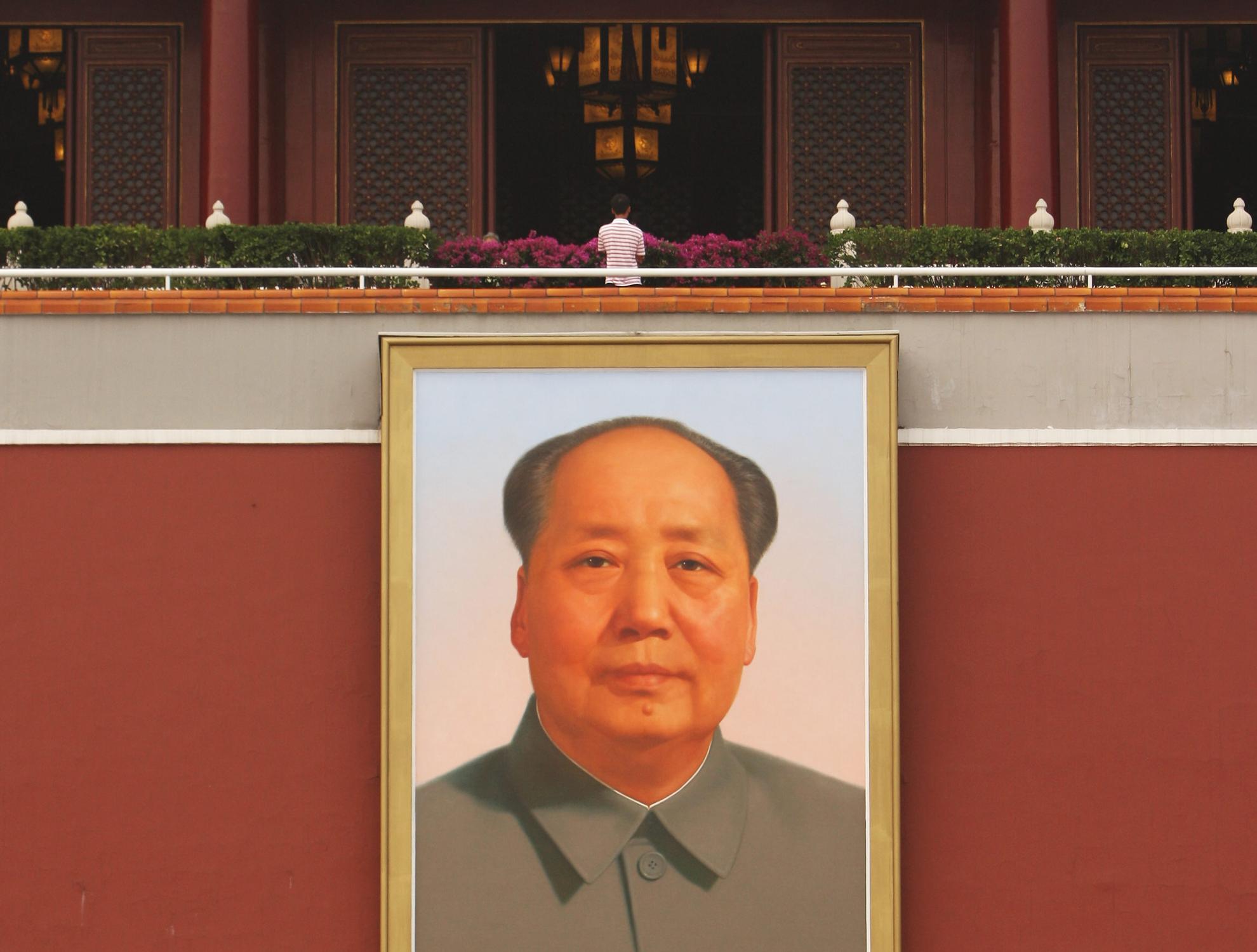

In 1966, China’s Communist leader Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in order to reassert his authority over the government.

He shut down universities and sent a majority of those with an education to labour camps in the countryside for “re-education”.

Mao died in 1976 but the revolution’s tormented and violent legacy resonated in Chinese politics and society for decades afterwards.

Dr Sui Yu grew up in China during this era. She migrated to Australia in 1988 to escape its devastating effects.

Now 60, Dr Yu is an Australian citizen with three sons, a hugely successful career as Australia’s first genetic pathologist and a lovely family home in Beaumont.

She tells her story to reporter KARA JUNG.

CHINA

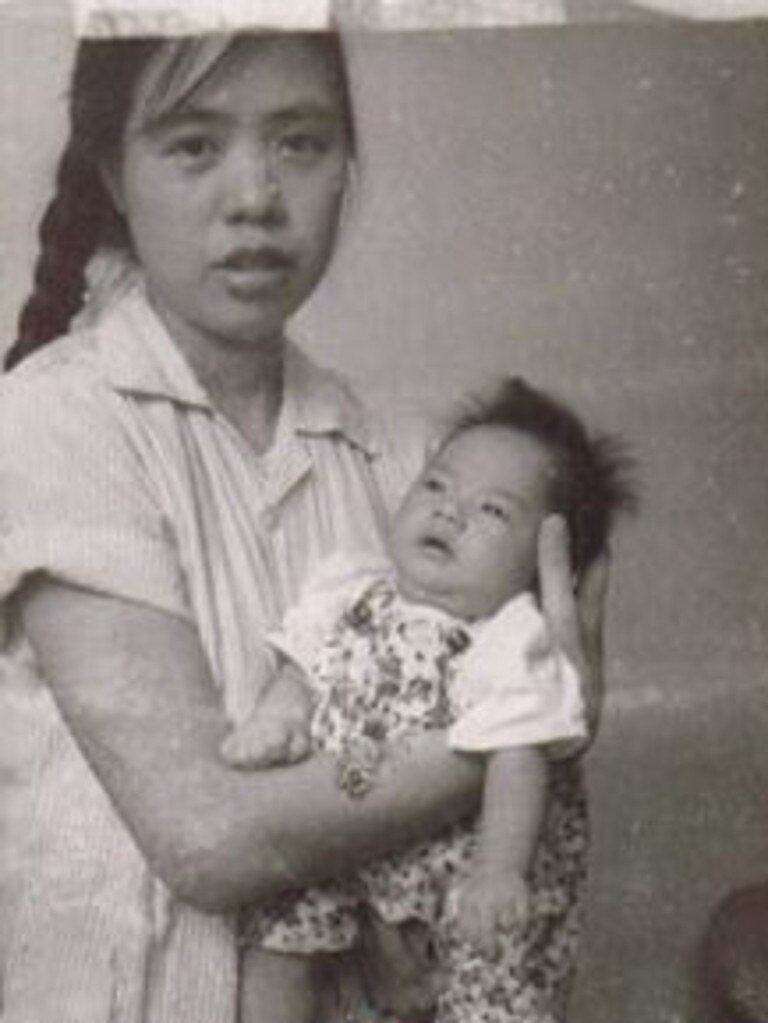

It was 1967 and my mother fell sick.

My father would go to the market to get a big rooster and take it to the hospital at least every week and whoever was there — all the doctors and nurses had been sent away to labour camps in the countryside — would hook up the chicken blood into my mother’s blood circulation.

I remember very vividly this new method of treatment — the Chicken Blood Treatment. It was one of Chairman Mao’s greatest victories where he believed it could treat everything, every sickness.

The Cultural Revolution had started.

The Chicken Blood Treatment was a common practice. There was even a book, I remember.

My mother had become sick and this was the treatment.

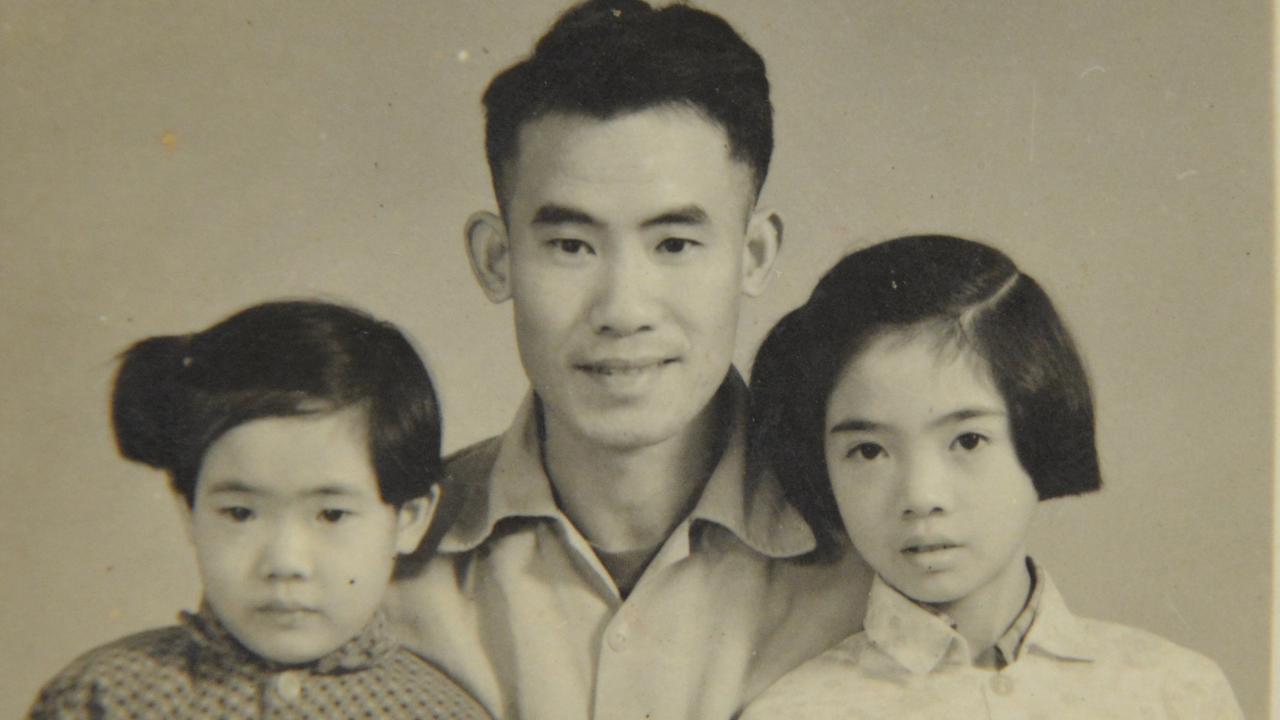

My mother died at the age of 32. I was nine and my sister was four.

I remember the last time I saw her. Her face was beyond recognition and I knew.

It was after that visit … she died.

Later on, when I studied medicine I realised that transplanting a foreign body, even into a healthy person, can kill someone; that it was likely her cause of death. But at the time I was only 9 years old and we must all follow Chairman Mao’s rules.

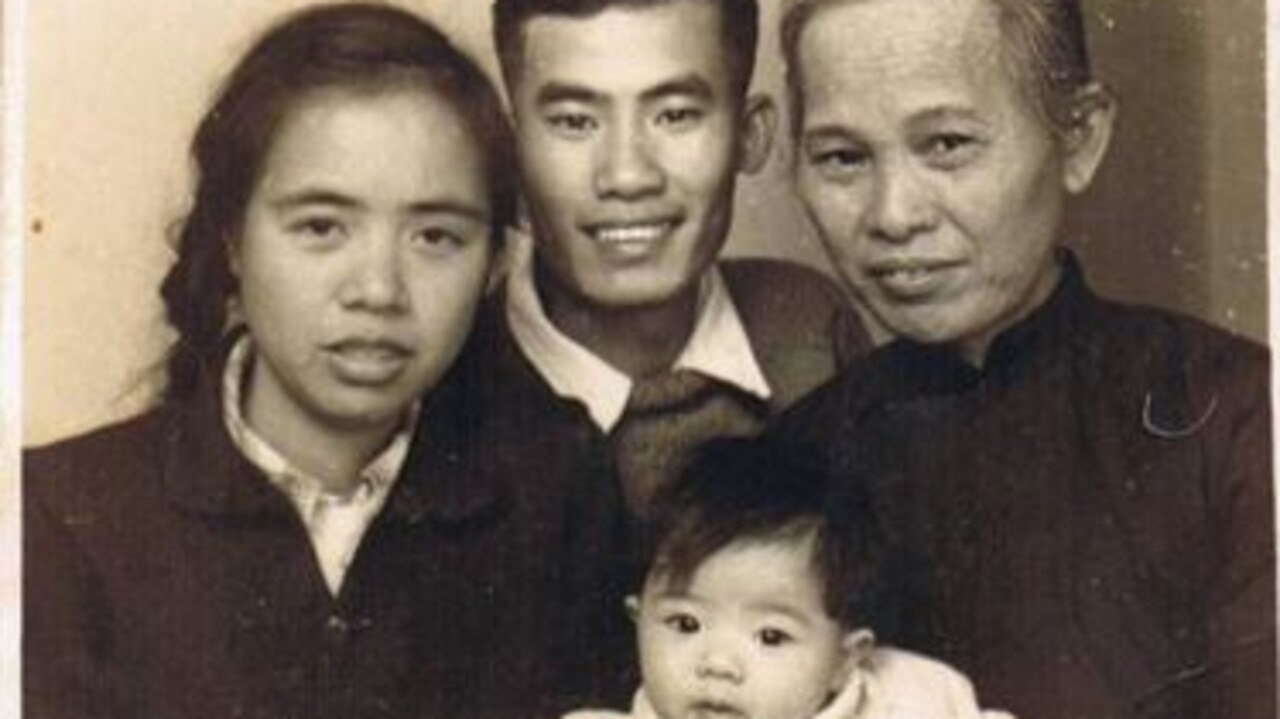

Both of my parents had a tertiary education and worked for the government. In 1949 the Communist Party took over the rule of China. My Grandfather moved to Singapore and encouraged them to come with him but they were excited to help build a new China.

But then the Cultural Revolution started.

My mother died and then my father got into trouble. The Cultural Revolution was against anyone who could think, basically.

My father was accused as the killer of my mother. And he was put in confinement. At least three times that I can remember between ‘67 and ‘73 he was taken. If he didn’t come home for dinner we would know he had been taken. That was the norm. People would disappear, or ‘jump’ off the third floor.

My father, he would disappear, then he would be released a few months later with no explanation.

He had begun to regret that he didn’t go to Singapore and had started to apply and that was a big no-no at the time — if you wanted to go abroad, you were a spy, as simple as that. He was educated. So maybe these are the reasons he was eventually sentenced to life in prison for being antirevolutionary in 1973. I was 15.

It was in a big sports stadium. People being sentenced were lined up with big heavy wooden boards, held up by wire around their necks. I was there. You had to go. Everyone had to go to these meetings. They put a cross on the big boards. They would put the people on the trucks, their necks weighed down by the boards, their heads bowed down from the weight. They would do this to humiliate them.

After he was sentenced, my teachers and people came down and said to us ‘you need to draw a line between your father because he is the enemy.’

Silence was the only power I had to their words. The only way I could show my resistance. Silence was the only way I could protest.

I remember as a child, in the summer we would all sleep outside of our building because it was so hot. My father would show me how to look at the stars and their names and he would teach me maths problems and tricks on how to solve them. These are some of my memories of him.

After he was put in jail, life changed overnight.

I was prohibited from joining the youth league, the Little Red Guards.

No one dared to talk or play with us. My sister was striped of her title of the primary school captain. My home was searched multiple times without warning for evidence of being antirevolutionary. They would come and turn it all upside down, go through drawers and cupboards.

Teachers and local council managers would meet with us often as we were ‘children of the class enemy’.

And then we were sent to very low-class accommodation.

The mental trauma was very painful.

But there were exceptions. My friend Tian Hui would walk 5km to visit us in the home we had been banished to. I wanted to give her 10 cents to catch the bus home but she insisted on walking.

My friend Chen Zi played with us and her parents, both Communist Party members, even invited me for dinner.

Another friend Juli Chen, she was nine years older than me, came to visit us with a small piece of meat and winter melon and we made soup. I asked her why she would further risk herself as she had been sent to the country for re-education. I remember her laughing and saying she was already in the most remote countryside: ‘If they kick me any further, I’ll be off the Earth’. She was very brave.

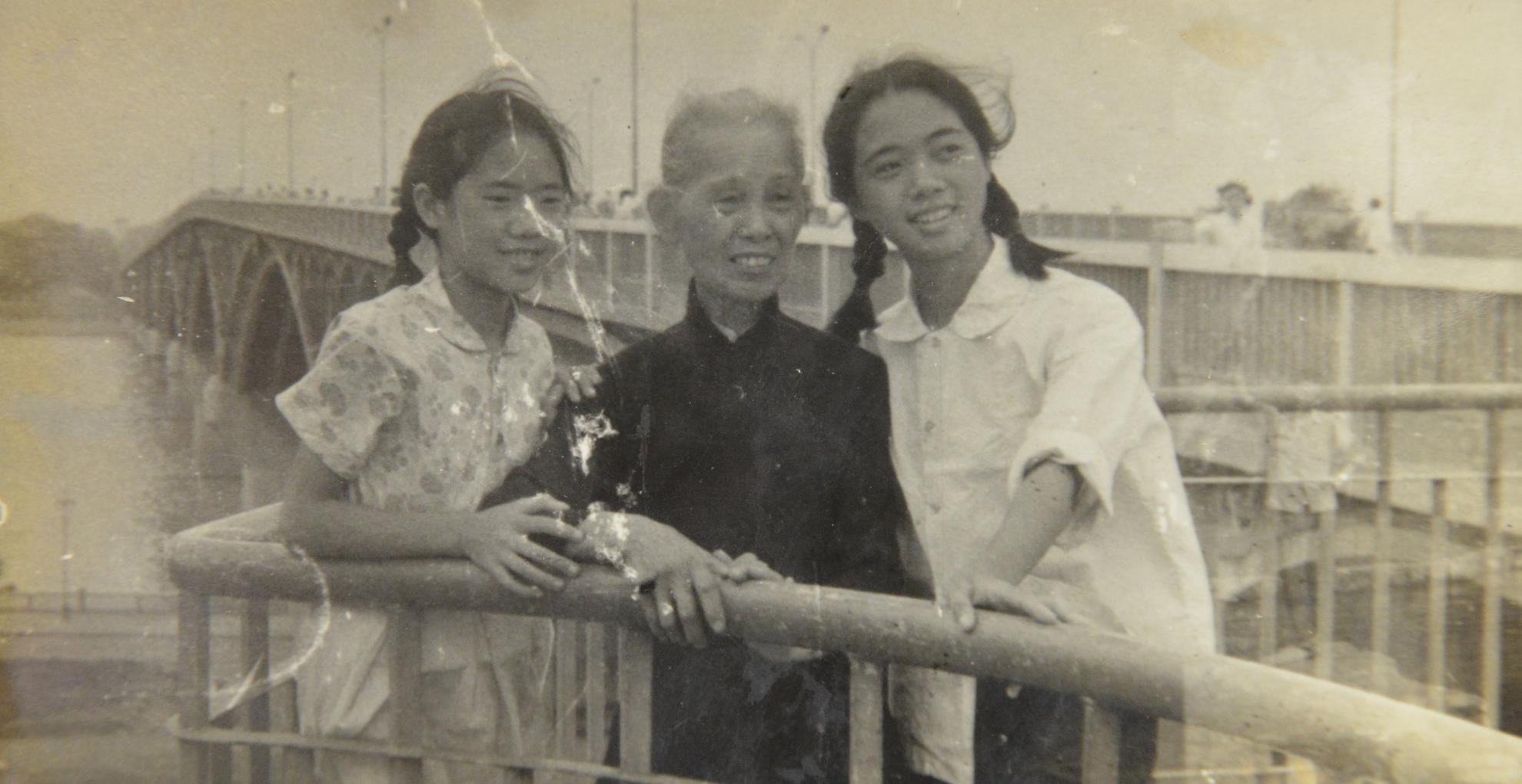

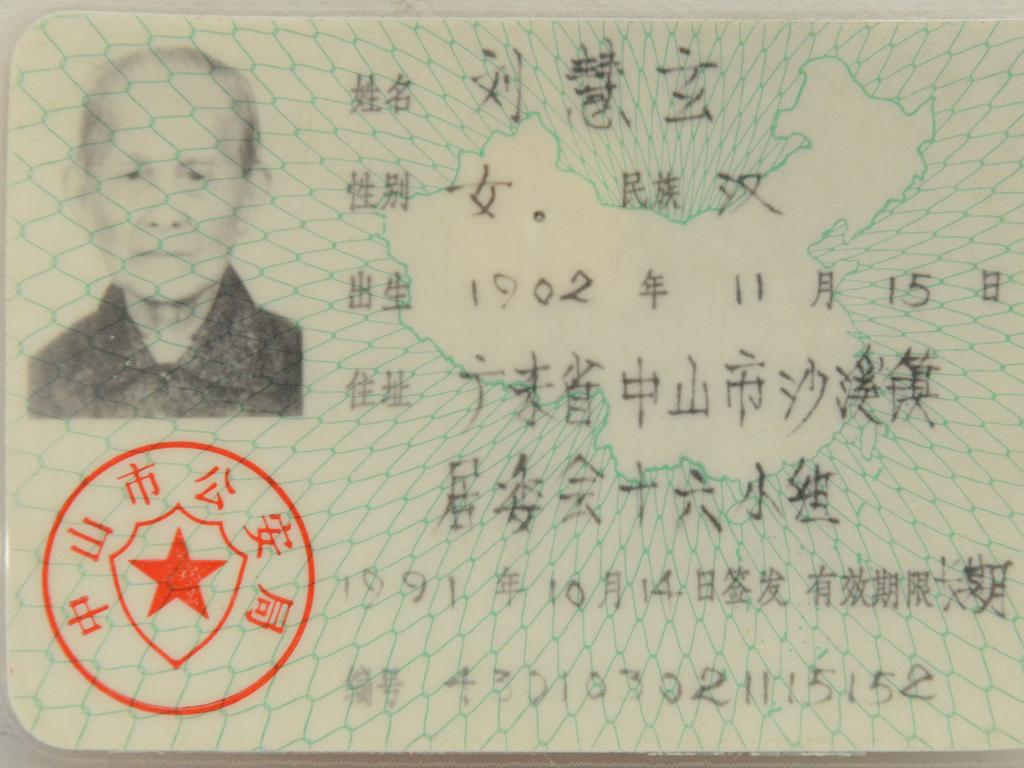

My Grandmother (Hui Xian Lui) taught us to make clothes and shoes, we raised pigeons as a protein source and bound waste paper into exercise books.

My sister and I were brought up by my Grandmother. My values, beliefs, resilience and self-sufficiency are from my Grandmother. She was always there — difficult times, good times.

We had no income.

I graduated from High School at 17. There were two possibilities. One, I be sent to the countryside to be re-educated. But the local council said because I have no income I would go to work.

I worked in tobacco companies taking the thick stem out of the leaves. The weight of the stems would determine how much they pay you. Then I worked in a candy factory hand-wrapping the lollies.

Then I worked for a construction company building four and five storey apartment buildings and concrete water towers. We would use the shoulder poles to transport the big concrete blocks. The water towers needed to be built in one piece so we did 72-hour shifts, non-stop through the day and night.

My grandmother was so worried I would slip and fall.

It was very hard physically, but the people in that industry were the bottom of society so there was not the discrimination; the people were friendly and supported you. There, I was very happy.

My grandmother looked after a baby for extra money. My sister used to put those tiny springs in the cigarette lighters, we would all sit around and help her. These things we did to survive. We lived in a four metre by four metre room.

At the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1977 I studied to go to university. I would read my books in my five minute breaks as we’d build the water towers.

I did very well. My score was enough to go to the very best universities in China. But the next day, the council people came to talk to me. They said ‘don’t think you will get into any university because the selection is not just on your score but based on the family background.’

I lost a lot of opportunities. It hurt.

I received an offer to go to Huangyang University, a much lower university, to study medicine. It wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to do aviation engineering but my teachers said no one with my background would be able to go near an aircraft and that I’d be lucky to get any offer. So I had decided on engineering.

We were surprised to get an offer at all. Medicine was my only chance.

Sometimes life happens like this and it’s meant to be.

The university was very basic. Blackouts often, intermittent tap water but no one complained because we were the lucky ones.

LEAVING CHINA

I wanted to go overseas but I kept getting pushed aside. I had never joined the Communist Party, my father was still in jail. These things together contributed to ongoing bad treatment. The revolution was over but the ideology was still there.

I was still being overlooked, still being punished.

I remember I had written a paper to be published. A colleague came to me one day and said ‘be careful, they have changed the ownership of that paper — your name is not on it anymore’.

I couldn’t live with that.

I went to the office, I asked to see it and asked where my name had gone. They said ‘that’s not for you to comment’.

So I took it. They followed me. I tore it apart. It didn’t go down well.

I couldn’t leave the university unless my supervisor released me. He said he would not let me go, he would not let me travel, he would not promote me like he had all the others, he would not raise my allowance like he had all the others.

I said to him: “God has not given you that right. We will see what the future holds”

People were amazed I dared to protest like that.

I knew if I lived in China long enough I would follow my father’s path.

I found a remote country town hospital in Canton and that’s how they released me — they were happy it was such a big step downhill that they let me go.

It was my only way to go.

I then started trying to move overseas.

I decided to be a self-funded student, but money was a significant challenge. I made $150USD a month, but a flight would cost $1000USD, and a term as a student would cost more than $1000USD plus living expenses.

That old friend, Juli Chen, had married in the US two years before. She knew I was desperate. She sent me $2000USD and became my financial sponsor.

She passed away a couple of years ago. I visited her in the US in 2014 and last year, when I went to the US, I stood before her grave.

It is rare and very precious to find true friends who will stand by you not just when things are well but in your worst moments. She was a true friend.

AUSTRALIA

I came to Australia in 1988. I was 30 years old.

I came as an English language student. I then started my PhD project on the molecular basis of fragile X syndrome at Adelaide University in 1989, while working in a uniform factory in Stepney.

I married and was a new mum writing my PhD.

My PhD supervisor and my boss Professor Grant Sutherland at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital shaped my professionalism in science and pathology and in managing people. He has been my role model in Australia.

(Dr Yu also became an Australian citizen in the mid-90s)

I passed my overseas doctors’ exams in 1997 in order to gain medical registration.

I became one of the first two — we graduated at the same time — genetic pathologists in Australia in 2002.

I became the head of the Department of Genetic Medicine in 2004 and have introduced new technologies — MLPA, microarray and microsatellite for molar pregnancies.

I am most proud of my contribution to science: discovering the cause of fragile X syndrome against strong international competition in France, the US and the UK.

The linear mapping of the syndrome did not make sense for five months. I would work into the night, but still we couldn’t work it out. One night, I had worked to 3am and then gone to bed. I had a dream, about it being a circle. I woke up and tested it. It worked. We had the smallest group and the smallest lab but Australia was the first to discover the molecular basis of fragile X syndrome.

I’m proud of my three boys. I am proud of doing the City to Bay every year for the last 14 years, climbing Mount Lofty every weekend, catching the travel bug, my friendships both here and in China.

I tell my boys they are so very lucky. When I landed in Australia, I landed in Melbourne. A week later I received a parcel with my purse. I had left it in the airport. That was my very first experience and the moment I realised I already loved Australia.

To this day I am moved by small acts of kindness everyday in Australia. The bus driver actually waiting for people running to the bus, stopping for an elderly lady and making sure she is sitting down before he drives, people bringing (excess) fruit and veggies from the garden to work to share. It’s little things that really show that people are caring of other people in this country.

In Australia I am in a minority and people have asked me if I feel racism: I don’t. Sometimes people shout ‘go back to your own country’ yes, but that is nothing like the discrimination I faced in China when I was part of the majority.

I love the festivals; Fringe, Greek Festival, the African Festival, the Moon Lantern Festival … It’s a lovely experience of multiculturalism. It is a safe place.

I am very grateful that Australia provides me with a lovely home without discrimination, without political pressure and without fear so that I can think and make decisions freely.

Most importantly, it gave me the opportunity to use my talent to contribute to science, to serve the people of this country and, in doing so, to live a fulfilling life.

I remind my children all the time that we are so lucky to live in this great country.

Adelaide is a lovely place to live; to call home.

Discover the flavours of China in Adelaide

- T Chow Restaurant: 68 Moonta Street, City

- Eastern Garden Restaurant: 185 The parade, Norwood

- Dumpling King in the food court: King William St, City

- Asian Grocery: 162 Henley Beach Road, Torrensville

- Hong Kong Grocery: 93 Grote Street, Adelaide

Significant dates in the Chinese calendar

- Chinese New Year: February 5, 2019, also known as the Spring Festival, this is the Year of the Pig, the twelfth and last of the zodiac animals and a symbol of wealth.

- OzAsia Festival: Australia’s leading international arts festival engaging with Asia, usually help in October-November in Adelaide.

- Moon Lantern Parade: In China it is also referred to as the Harvest Moon Festival or Mid-Autumn Festival. In Adelaide it is celebrated as part of the OzAsia festival with a huge handmade lanterns, the Lucky Dumpling Market, fireworks, music and family entertainment. 2019 dates TBC.

- Duan Wu Festival: also known as the Dragon Boat Festival, occurs near the Summer Solstice in May to show respect to ones parents, relatives and ancestors. Dr Yu celebrates at home with family making Zhong Zhi — sticky rice wrapped in bamboo leaves

- Qingming Festival: Also known as the Sweeping of the Tombs, where people offer sacrifices (food and flowers) to their ancestors and sweep their tombs. Usually falls on April 4 or 5

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Cast your vote for SA’s best hairdresser of 2025

They’re the masters of hair who can tackle anything from cutting, to colouring – help us crown the state’s top hairdresser. Meet your 20 finalists and vote now.

‘They are among us’: SA’s vile child sexual offenders revealed

So you think a pedophile is the stereotypical creep in the corner? Think again. 2025’s class of infamy shows child sexual offenders come from all walks of life.