The Way of the Warrior: What makes Natasha Wanganeen tick?

Activist, actor, community leader. There’s a lot going on in Natasha Wanganeen’s life – but who is she and what is she fighting for?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Something about the black lipstick and fierce gaze of South Australian actor and activist Natasha Wanganeen makes her look a lot angrier than she is. She can be a race warrior when she has to but there is a softer side as well. No wonder people think I’m always cross, she laughs, looking at herself in a magazine.

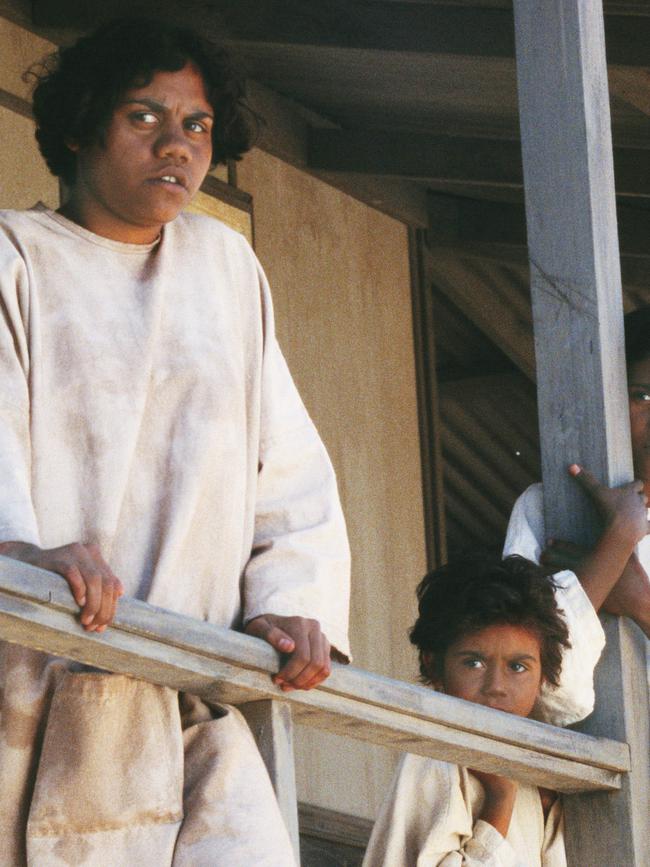

She is unrecognisable as the shy mission girl who stumbled into a role in the seminal film about the Stolen Generation and the journey back to country of three young Indigenous girls, Rabbit Proof Fence.

She was 15 and part of the Port Youth Theatre Workshop run by her aunt, the late Josie Agius. She remembers one day being asked to stay behind with two other girls who were called into a room, one by one. The first two came out smiling but all Wanganeen could think about was being late home and getting into trouble.

“I didn’t know what this was, didn’t know it was an audition,” she says. “I didn’t know how these things go, I’d never done anything like that before.”

She was told on the way in that there was a man in there who wasn’t listening and she had to make him get up and grab a can of Coke from the other side of the room. She told them she was sure that if they asked him again, he would. No, you’ve got to make him, they told her.

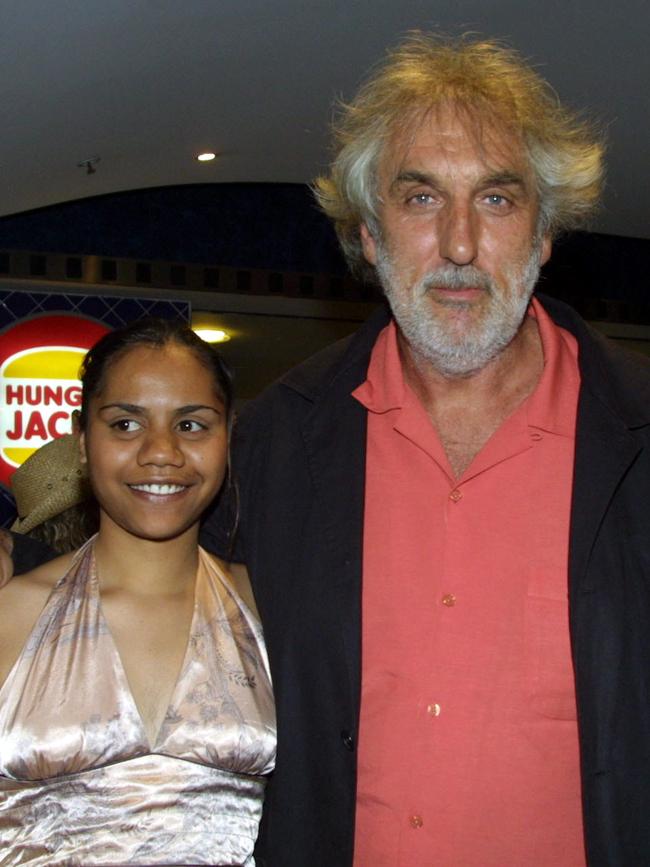

She walked in, whistling like a prison guard, went up to him – it was the director, Phillip Noyce – kicked his chair and told him to get up and get a can of Coke. He pretended to be asleep then snarled, “what do you want?”. She repeated the order and when he refused, she kicked the chair and barked at him to get up and get that can of Coke.

“He stood up and I didn’t realise how big Phillip Noyce was, I was only 15, so I was like ‘Oh shit!’,” she laughs. “He said ‘what are you going to do about it?’ and I said ‘you don’t want to know’ and then he just laughed at me and started clapping.”

When she was told she would be in a movie (she was cast as Nina, the dormitory boss) she refused to believe it and made the producers ring her parents to say where she was. “He said ‘you’ve got a role in a movie’ and I said ‘don’t lie to me, I’m going to get grounded, the sun’s gone down, I’m going to get cursed’,” she says.

Only when Noyce took her home and sat with her parents was she convinced. At that age she had no idea how much the movie would say about what had gone wrong between First Nation and colonial Australians but it turned out to be just the kind of film that Wanganeen still wants to make.

Stories of disadvantage had burrowed deep under her skingrowing up at the Point Pearce mission, where her grandparents had needed white permission to marry and to travel around Adelaide. She knew all about an Australia which had a “them and us”.

“I was very aware of the black and white issue growing up, I was raised in a place that was built on segregation pretty much,” she says.

Twenty years later and Wanganeen is a leader in her community as well as a film and television actor who has never been busier.

Juggling a career with black activism might look like a professional risk but it has not held her back and in some ways may have helped. While her role as a line cook in the ABC series about bad boy chef Easton West, Aftertaste, had nothing to do with race, the sci-fi, Indigenous series Firebite, directed by Warwick Thornton and streaming now on AMC +, feels like more of a natural place to find her. In it, she plays a zombified mother, Rona, who has virtually no dialogue in Season 1 after preparations that stretched to five hours of prosthetics and makeup.

“I’ve never had to be quiet and still so much in any of my roles, I am proud of myself,” Wanganeen says. “Being catatonic for most of the first series is pretty hard when you’re used to running around.”

The series, a brilliantly wicked allegory for colonisation about vampires swarming on a small outback town (with Coober Pedy standing in for Opal City) hammers home a well-made point about Indigenous people on country fighting off outsiders who want their blood and their land, and it does so with humour and style, not bitterness. In the series, which will have three seasons, Wanganeen plays the mother of the young vampire hunter Shanika (South Australian actor Shantae Barnes-Cowan).

“It’s a beautiful character; a lot of mums get taken away and end up in situations where they can’t get back to their kid, so there is that dynamic of lost children being reunited with their mothers,” she says.

“Only it’s the reverse – the mother has been taken and the kid has to go and find her. There’s a lot of strength in there, and humour, all the things that have carried us through the last 200 years.”

Making screen work about Indigenous history can mean living through some of the pain. In 2017, Wanganeen joined the cast of The Secret River when it performed at Anstey Hill quarry as part of the Adelaide Festival. She played the mother, Gilyagan, in Kate Grenville’s confronting story about the conflict between black Australians and white settlers. A year earlier, she performed in the television series in a role other actors had turned down, that of the chained sex slave abused by a cruel settler, Smasher, played by Tim Minchin. She thought hard about taking it on and says she endured some backlash because of it.

“Some community members thought it wasn’t right to be part of that show but I explained to them, from my point of view, I would rather be in a film that tells our stories and highlights the brutality of what our women went through than not say anything,” she says.

“If it’s disrespecting culture, disrespecting our people and our history, I won’t be part of that but shedding light on the truth, I will happily be involved with.”

It was tough to act the experience out for the sake of the series, even as well-supported actors, and it bonded Wanganeen and Minchin for life. Wanganeen says they were both completely broken by it, particularly Minchin who was in his first acting role and who she now calls “a brother”.

“That day was very hard on him because he’s got such a universal heart and he doesn’t want to see any human being in a position like that,” she says.

Once the scene finished, Wanganeen was wrapped in a blanket on set and then went looking for Minchin who was down by the river, in tears. He never wanted to see that again in his life, he told her.

“I told him it’s good, that 200 years ago you would be on that side of the road and I’d be on this side and we wouldn’t even look at each other but we’re here, making a film about our history,” she says. “Take that and be proud of it. It was a beautiful moment, as a white man and a black woman to realise how big that moment was.”

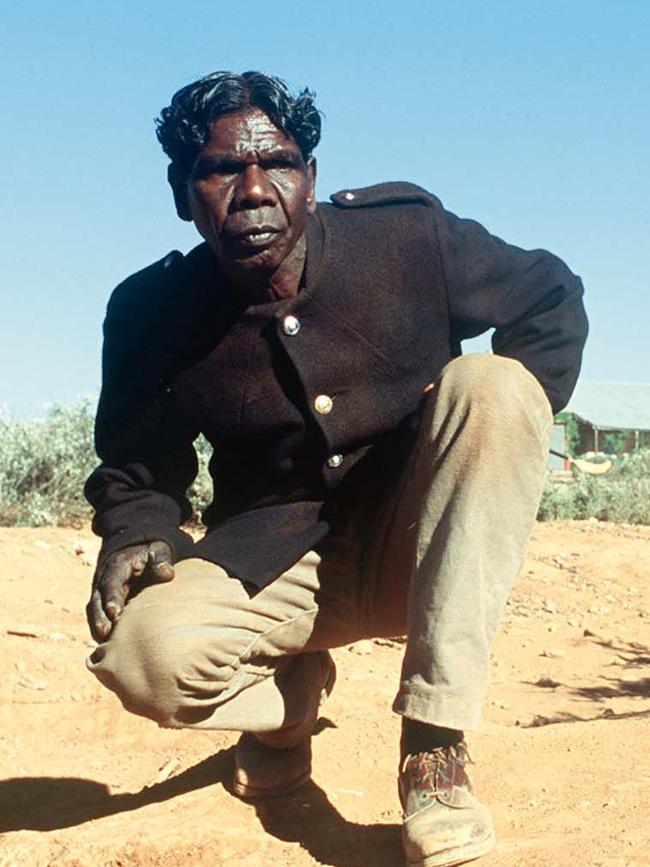

Wanganeen, the mother of Tjarrah, 11, is powerfully connected to her community with family and blood ties extending around Australia. On the set of Firebite she counted among cast and crew at least three relatives including two from Western Australia, and she is a cousin of former AFL footballer, Gavin Wanganeen. But her greatest mentor was and always will be David Gulpilil who she met on the set of Rabbit Proof Fence.

She says she first felt his presence rather than saw him.

“Then I looked and I was staring at him thinking ‘my God, that’s Batman, that’s Superman, that’s our biggest hero right there’ and when he looked at me, I didn’t know where to look,” she says. “He almost giggled at me because he knew, and I looked back at him and he went ‘you right?’ and I went ‘I’m OK, yep’.”

Each time she saw him after that, she would edge closer and eventually they began talking about where they were from. He was missing his daughter and Wanganeen missed her father and it helped to create a bond.

“We’d make fun of other people on set because we had a very simple way of doing things and they were making it really complicated and we’d sit and giggle about it,” she says.

His death, no matter how much it was expected, was a blow. Wanganeen had stayed in touch with Gulpilil who she called Bipi (Yolngu for uncle) over the years and would take him chocolates in hospital in Darwin or join him for lunch and a laugh. When he was sick, she would sneak him in chocolate croissants, hot chocolate and drawing books.

“The bond we had was unique and what I got from him you can only get when you take your shoes off and put your feet in the dirt,” she says. “He called me his shadow, I called him Yoda. He was probably my greatest teacher.”

He died last year at around the same time as her grandfather and brother and she tears up at the memory of so much loss. She was part of his inner circle who came together for a ceremony at Victor Harbor to sing his remains on the start of their 3000km journey back to his home in Arnhem Land.

His body is being held in a morgue until after the wet season when his country can be accessed and he will finally be returned home. Wanganeen says Gulpilil, who died from lung cancer and emphysema, was ill on the South Australian set of Cargo, the 2017 zombie movie starring Martin Freeman, although for cultural reasons she couldn’t say anything and had to wait until he told her.

Today she is angry that he was showered with accolades only at the end, and says it might have helped him live longer if it had happened sooner.

“If he had that 10 years ago, maybe he would have started appreciating himself and looking after himself more,” she says. “It is hard to watch everyone in the industry cry over him when they haven’t put the effort in over him, or acknowledged the way it should have been.”

For all the frustration and anger on behalf of her people, Wanganeen has a wide, lovely smile and a playful sense of fun. There is hardly a photo of her on social media where she isn’t poking out her tongue or pulling a face and she is a proud child of the 1980s whose movie loves are over-the-top action, horror or sci-fi like Rambo, Predator, Alien, Freddy Krueger. She made it into Adelaide’s first brush with big-action blockbusters, the $55m Mortal Kombat that was filmed and produced here over 2019-20, although not in recognisable form. She and two others became prototypes who were replicated countless times to make a town full of people.

Her career is booming but community business keeps drawing her in. Last September, her cousin Charlene Warrior, 21, disappeared after picking up her daughter from the house of her former partner in the small town of Bute on Yorke Peninsula. When she disappeared, Wanganeen was asked by Warrior’s parents and siblings to help and she posted messages tagging Warrior and asking people to look out for her.

After Warrior was found dead, Wanganeen helped organise food and support for her family as well as a vigil and march. She says the community brought in an independent coroner after the family disputed the initial finding of suicide and Warrior’s death is now under investigation.

“It was a lot of community work but if people look towards you and say ‘will you help us out?’ I will say ‘yes’ because the community raised me,” she says.

Included in last year’s personal tragedies was the death of Wanganeen’s brother in sad circumstances she says are also under investigation.

“Because it involves other Indigenous people in the community, we’ve got to be very sensitive about it,” she says.

“He died in Adelaide, not far from here. I’ve never known a day of my life without him and it was eight days after my birthday … pretty devastating.”

In recent years, Wanganeen has emerged as a leader and rallying point for protest on January 26, and she again this year took up a position in Victoria Square where speakers and dancers provided an alternate view of what the day means.

“Invasion Day, Survival Day – I call it Survival Day because I choose to find the power in it, because we are still here,” she says. “Those days are always difficult for me personally because I’ve got my whole community and people around the country who I’ve got to stand up for.”

Her solution to the conflict over Australia Day: move it to another date that offers a broader and more inclusive meaning that can be celebrated by all Australians, not just some.

“We need to rename it, reshape it and put it on a whole new day because (January 26) has got way too much poison in it, there’s too much bad blood there,” she says. “May as well have a clean slate and everyone can jump on board.”

Professionally, she has hit her stride with small or bigger parts in most of the film and television that is made here. She has just completed The Mountain, made by Tasmanian based auteur director Rolf de Heer, about a black woman abandoned in a cage in the middle of the desert. Wanganeen calls it a silent western with a soundtrack that does not include dialogue, only sounds, noises and gestures.

“You kind of have to figure it out … Rolf is amazing at what he does,” she says.

Coming up this year she hopes to return to Firebite for another season, as well as Second Chance, a family series about gymnastics in which she plays a former national champion.

She is also in the running for at least two other films and a part in a contemporary thriller that will star renowned UK independent actor Tilda Swinton.

“Every time I think of her, I think ‘she’s the white witch from Narnia!’,” Wanganeen says. “Her craft is amazing. It would be very cool to work with her. And she is very tall. I’ll have to stand on an apple crate.”

On top of that, she is in talks about making a feature film she has written that encompasses her Aboriginality as well as her 1980s blockbuster aesthetic. She calls it an adventure fantasy with battle scenes, lightning bolts and people riding giant goannas down Flinders Ranges’ cliffs. The cast will be almost entirely Aboriginal with a lot of AC/DC music. “Tim Minchin has put up his hand to play a bush mouse, a lot of actors want a piece of it,” she says. “It’s about people who can change into their totems like cockatoos, emus and snakes.”

She is in development talks with respected SA-based producer Lisa Scott (Wolf Creek, The Tourist) and says there is interest from streaming services and Screen Australia.

“I’d love to be in it but I’m also aware there are other young actors who are coming up who deserve an opportunity to get out there and show the country what they can do,” she says. “It will be like Clash of the Titans but it’s our mob.”