A talented, turbulent soul: The last days of David Dalaithngu

David Dalaithngu was a legend of Australian film but also a troubled soul trapped between two worlds. Read this powerful last profile of the great artist from SA Weekend.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EDITOR'S NOTE: David Dalaithngu's family has given permission for his name and image to continue to be used after his death, in accordance with his wishes.

This profile of David Dalaithngu was originally published in September 2019. His death was announced by Premier Steven Marshall on November 29, 2021.

-------

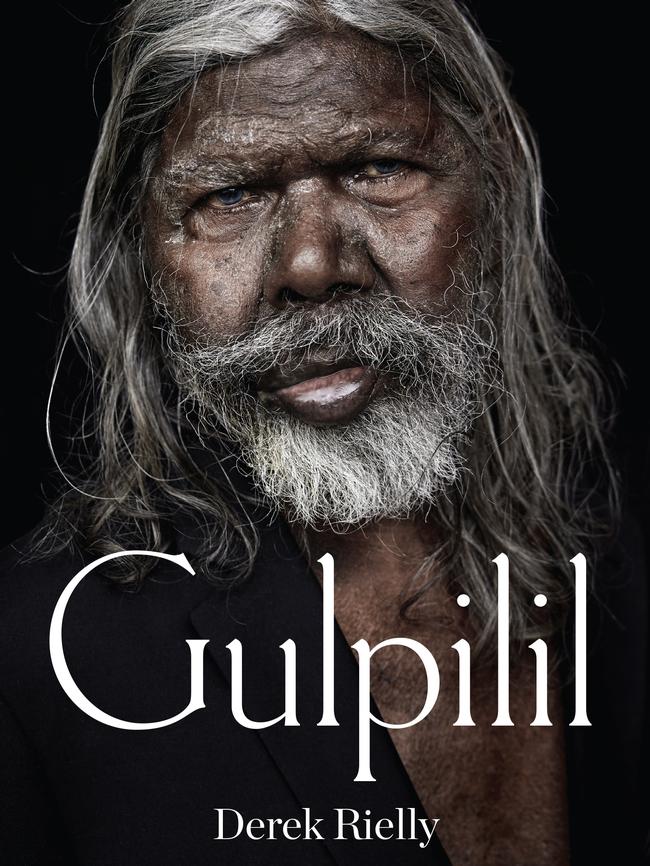

After completing Wednesdays With Bob in 2017, Derek Rielly’s colourful record of the Wednesdays spent listening to Bob Hawke’s stories while soaking up the ex-PM’s charisma, Rielly was looking for someone to do next.

He was keen on David Dalaithngu, who he considers Australia’s finest actor, but wasn’t sure how to contact him.

An Aboriginal arts curator he knew thought he might be up north somewhere near Maningrida in Arnhem Land but no one was really sure.

“He’s a hard man to find from what I’d heard, no one knew where he was,” says Rielly. “All these literary contacts and people in the arts world were looking for him.”

Then he ran into a mate at the beach.

Rielly is not a conventional writer; he is a maverick personality from a surfing background who is part of the Bondi culture. After a swim he was talking to actor Dan Wyllie who was in Charlie’s Country and knew David Dalaithngu.

More importantly, he knew Dalaithngu’s close friend and unofficial guardian Rolf de Heer who saved Dalaithngu from near death from alcoholism by writing Charlie’s Country with him, which won Dalaithngu a best actor award in 2014 at Cannes.

“I told Wyllie I was trying to do Gulpilil (Dalaithngu) and Wyllie said, ‘You’d better hurry up, he’s got lung cancer’,” Rielly says.

A few months later Rielly drove into the hamlet of Murray Bridge, about 76km southeast from Adelaide, where Dalaithngu has been living since 2015.

Dalaithngu had gone there to get away from the relentless humbugging, the demands for money from sectors of the indigenous community who believed his stardom had bestowed on him limitless wealth.

De Heer had paved the way already but Dalaithngu was more than happy to be the subject of an unconventional biography.

He is in the final stages of lung cancer and emphysema, and the fact he is still here is something of a miracle.

A rare sighting at the October 2018 Adelaide Film Festival was thought likely to be his last but there he was in January this year on the red carpet at the Adelaide launch of Storm Boy where he was photographed with Trevor Jamieson, the indigenous actor who played the role Dalaithngu made his own, Fingerbone Bill, in Storm Boy in 1976.

“It’s extraordinary, no one had ever done a book about him,” says Rielly. “I know he’s a mercurial character and hard to find but to me he is the great Australian actor.”

Rielly tried sitting down and interviewing him but gave up after a few sessions. Dalaithngu, who speaks at least six indigenous languages, would go off on tangents, often in language, and wasn’t easy to follow.

“He talks a bit like a Dr Seuss rhythm: ‘We go hunting, hunting we go’, it’s poetic,” says Rielly.

Dalaithngu lives in Murray Bridge with friend and carer Mary Hood, a former aged care nurse originally from South Australia who Dalaithngu and his wife Miriam met in Darwin.

They bicker affectionately like an old married couple, says Rielly, and the townhouse is so small he was confronted with Dalaithngu’s beautifully sculpted, weathered face the minute he walked in.

He decided the best approach was to just be with him and absorb who he was.

One day they watched The Tracker together, de Heer’s film set in the 1920s about a tracker on the trail of a murderer which shows Dalaithngu in all his physical grace and glory, moving silently, barefoot, through the bush.

On one day he opened up unexpectedly about his family and country but at other times he was withdrawn and quiet. “There were so many similarities with Hawke,” Rielly says. “Everyone loves him, women love him, and you’re thrilled to be in their orbit even if it’s just briefly.”

Dalaithngu’s story is woven through the book which features interviews with some of the people who he has worked with and love him, including actors Jack Thompson and Paul Hogan, whose Crocodile Dundee was probably Dalaithngu’s biggest international movie.

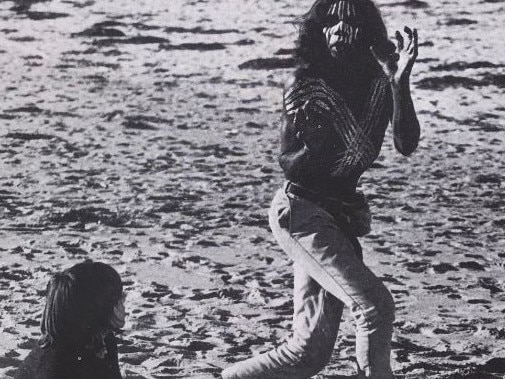

Thompson was a young actor when he first saw Dalaithngu in Walkabout, the story of a schoolgirl and her brother who are stranded in the desert. He had marvelled at what a cultural advance it was to see a young Aboriginal man portrayed as attractive, sexy even, in the eyes of a young white girl.

It was a breakthrough for Dalaithngu too, in his first role as an actor. He was 18 and it is something of a marvel to understand that Dalaithngu was a first contact Aboriginal who did not see a white man until he was five. Rielly recounts how Dalaithngu and a friend, Bobby Punnunr, saw a missionary seaplane in East Arnhem Land in 1958 and fled in terror.

Just over a decade later he was cast as Black Boy in Walkabout, directed by Nicholas Roeg who the previous year had made Performance with Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg.

It changed Dalaithngu’s life in so many ways, giving him an acting career that five years later saw him cast in Storm Boy.

It also introduced him to the Australian character actor, John Meillon (They’re a Weird Mob) who was a well known larrikin Aussie and a drunk. Rielly says Dalaithngu took the actor’s carousing to be a kind of white man’s corroboree and happily joined in.

“I think he thought that was the way it was done,” Rielly says.

“A movie handler talks about this, that David saw it and thought that’s what you do on film sets, the drugs and booze and sex. Yes, he was vulnerable but he did seem to enjoy it.”

It was a fork in the road that took him away from country. Apart from exposing him to temptations that he was ill-equipped to handle, it also displaced him from his culture before he was fully initiated.

He was an Aboriginal straddling black and white culture, not really at home in either.

“My friend David Gulpilil (Dalaithngu) is a troubled soul,” Rolf de Heer wrote in press notes for Charlie’s Country (which Rielly quotes). “I sometimes liken his plight to that of the great Australian painter Albert Namatjira who was likewise unable to reconcile the two cultures he had to live in, his own, and ours.”

He was in trouble in ways that are hard to understand. Even after Storm Boy introduced Dalaithngu to a broad and adoring audience for the way he lit up the screen as a source of wisdom for the young Mike Kingsley, he was in trouble with the indigenous community. The Eagle dance he performs on the beach in the film was not his own to perform, a cardinal breach of tribal etiquette.

“The dance belonged to some other tribe and he got into trouble for it,” says Rielly. “In The Tracker there is a scene where he just starts dancing and it’s the first time in his career that he has danced his own. He was so excited to own that dance, he didn’t need permission to do it.”

Drinking took a terrible toll. Dalaithngu tells stories of partying with Jimi Hendrix and Bob Marley, and meeting the Queen, but he would spend periods in the long grass in Darwin, drinking hopelessly and becoming stupid with alcohol. In 2011, he was sentenced to a year in jail after breaking Miriam’s arm with a broom in a drunken fight. In jail, thin, ill, and close to death, he was visited by de Heer who laid it on the line, and promised him a film. He gave up drinking, made Charlie’s Country and began to live again.

Interwoven with Dalaithngu’s drinking was the cultural and financial stress of meeting the expectations of family and community. Rielly relates a story about Dalaithngu being paid a large sum of money in cash, for Peter Weir’s film The Last Wave, in a role Weir wrote for him. Dalaithngu ran into a friend, Richard Trudgen, in Darwin – it was around 1978 – and peeled off $32,000 for Trudgen. “Give this to my mother,” he said. The rest, an even bigger wad, was spent on partying.

A few days later he was back at Trudgen’s house, broke, trying to organise a Government welfare payment.

Dalaithngu is not and never was a wealthy man.

He thought it was better to take the cash and never entered into long-term royalty agreements. He did not save his money, but then nor could he. His obligations to his community were such that he had to share whatever he had.

“Hey David, wouldn’t mind a Toyota!” they would call out. Some would stick their hands into the windows of his car, asking for money.

“In Darwin, it’s gimme, gimme, gimme,” Mary Hood told Rielly.

“I’ve had him sitting in the front of a car with a six-pack in his lap and there’s all these hands coming through the window trying to grab ‘em.”

There is no suggestion that Dalaithngu was ripped off in his films but Rielly says, in Dalaithngu’s eyes, he was.

In 2004 Dalaithngu performed in a one-man Adelaide Festival show Gulpilil, directed by Neil Armfield. The show’s writer, Reg Cribb, told Rielly there was conflict and jealousy between Dalaithngu and people in his home in Raminginging.

“He’s always crying poor,” he says. “He’ll come in and he’ll give away all the money he made on a film, sometimes pretty good money. He’ll give it all away. And everyone expected him to.”

Dalaithngu said in the show he was underpaid for Crocodile Dundee because he received only $10,000 for his part. But Rielly says to bear in mind this was 1993, and he was only in one very short scene.

“Because it has made so much money, I think, through David’s eyes, he was ripped off,” says Rielly. “I think (his situation) is to do with the fact he would give the money away and he wasn’t a great saver.”

In 2017, after the move to South Australia, Dalaithngu began vomiting at night and developed pain in his right shoulder. When he was told one of his lungs had multiple shadows he asked, “Can’t you cut it out?”

The answer was no and he was given a few months to live.

Last year Hood found him slumped and lifeless in his plastic shower chair, the water still running. She pulled back the shower curtain and found Dalaithngu with no breath and no pulse. While her son called the ambulance, she ran to get the bottle of concentrated oxygen that emphysema sufferers depend on to breathe. She put the tube into his nostrils and Dalaithngu stirred.

Having been given a diagnosis that ran out two years ago, Dalaithngu is at the moment remarkably stable. He underwent immunotherapy in Adelaide, which seems to have helped prolong his life. He can still be quite animated and, while frail, he walks with a cane.

He has also recently had cataract surgery which will, oddly, remove the bluish colour his eyes had taken on, returning them to brown.

Rielly says a close friend in South Australia describes him as being like an old wounded crocodile who takes one breath every six hours.

“You shoot him and eight hours later he comes back and bites you,” Rielly says. “He’s stabilised and seems OK.”

Dalaithngu’s legacy is not in doubt. In a video made a few months ago for a NAIDOC lifetime achievement award, Dalaithngu asked to be remembered.

“Never forget me. While I am here, I will never forget you,” he said.

He changed the way indigenous people were seen in Australia and internationally, and did so knowingly, with charisma.

“He is one of the great links with 60,000 years of Australian history because he grew up traditionally,” said Australian director Philip Noyce who cast Dalaithngu in Rabbit Proof Fence. “He knows and he understands and transmits all the beauty of indigenous Australian culture, its practices, its history. And he carries that with him with … huge … dignity into every role that he’s played.”

Dalaithngu understands his impact and is sometimes bitter about his experiences but on other days, the good days, he is not bitter at all.

On his wall in Murray Bridge hangs a framed, personal letter written to Dalaithngu by the South Australian Premier, Steven Marshall, addressing his ill health and his continued fight for life. In it, Marshall reassured him that come what may he will be remembered.

“I understand you are fighting a mighty battle with cancer and you continue to defy! Nothing would surprise me given your extraordinary spirit,” Marshall wrote. “Go well, Mr Gulpilil (Dalaithngu), and know that your legacy will continue to be honoured and respected by us all.”

Edited extract from Gulpilil by Derek Rielly, published by Pan Macmillan, RRP $29.99. Out now