The remarkable life of Ed Ebsary, believed to be SA’s last Kokoda digger

In the shadow of Anzac Day, we remember the remarkable life and bravery of Ed Ebsary, believed to have been the last surviving South Australian who fought in the Kokoda campaign.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 1919, a few weeks before the start of the annual grain harvest in the Hundred of Barunga in South Australia’s Mid North, a boy was born. In the early hours of Wednesday, October 15, as a soft spring was making way for another scorching summer across the broad swathes of barley and wheat, a cry was heard coming from the bedroom of a farmhouse on Section 247.

Edgar James Ebsary entered the world, the fourth child of farmer Edgar Harold Ebsary and his wife, Catherine Evelyn Olive Ebsary (nee Bessell).

From the beginning, Ed was a true son of the stubble, with his bond to local community and the land on which he was born only interrupted by the advent of World War II.

Despite the hardships of being a teenager in the Great Depression, the vagaries of rural life working first with his father and then on his own land, making the best of both the booms and busts of farming in a fickle, sometimes merciless landscape, Ed’s stoic, wise and gentle presence in his family, his community and among his military brothers in arms would span more than a century.

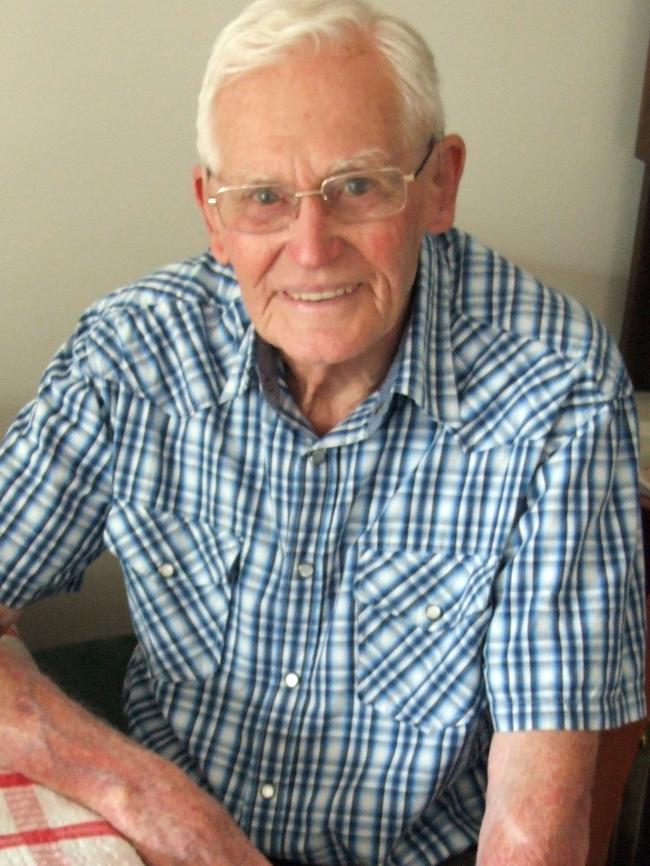

The oldest and last surviving member of the South Australian2/27th Battalion Australian Imperial Force (AIF) who saw action in the Middle East and Papua New Guinea during World War II, Edgar James Ebsary (SX9760) died earlier this year, aged 102.

Ed survived the diseases, dangers and hardships of jungle warfare, and was first wounded a few weeks before his 24th birthday at Mission Ridge on the Kokoda Track in the Owen Stanley Ranges in September 1942 and again a few months later at Gona during the Battle of the Beachheads on the northern coast of Papua. He died peacefully at Barunga Village, Port Broughton, in South Australia’s Mid North, on Thursday, January 13, 2022.

A self-made man, Ed left school aged 13 to workon his father’s farm. Dedicated and humble, his civilian life was focused on community and family. To those who knew him, he was truly a “gentle man”.

When he was in his 80s, he recounted his life in A Rough Rundown of The Life of Ed Ebsary. It was, he said, the “story of a very ordinary Australian”. But Ed was no ordinary bloke.

The fourth child, his birth followed sisters Ruth and Ila, and Mary who died in infancy. Another sister, Joy, was born a year after Ed and three years later his brother, Colin (Bob), was born. Ed remembered the tough times and his parents’ long hours working on the farm, often from before sun-up to after sundown, adding: “It certainly took real love of family (and each other) to endure the rugged conditions to start the kids on the best possible track (for life).”

Ed learnt those lessons well and applied them to his own life’s journey.

Ed gained his Qualifying Certificate at Barunga School at the age of 12½, but because he was considered too small to harness and manage draft horses, he spent another year in Grade 7. From the age of 10 until leaving school, he worked for his father as a tally boy at Barunga Gap during the Christmas holidays.

Ed’s father was a grain agent at the Barunga Gap wheat stacks and Ed’s job was to weigh each bag of grain, mark the weight on the bag with a piece of cane dipped in ink, enter the weight in a tally book and write out a cart note to enable the grower to claim his payment at the end of the season.

After leaving school, Ed worked on the farm, picking up pointers and skills from his father and hired farmhands, helping mend fences, feeding, grooming and handling the farm’s two teams of horses and, on wet days, trimming the horses’ hoofs and firing up the forge for blacksmithing jobs.

The good years produced quality fat lambs, which Ed drove to market at nearby Snowtown riding his pony, helped by a sheep dog.

When the Great Depression cut incomes, many farmers resorted to horse-drawn jinkers for local travel, putting their motor cars on wooden blocks in the implement shed to prevent the tyres from perishing.

Through the tough times Ed said there was a remarkable sense of humour, especially among the kids, who made the most of life. In his teenage years, Ed played tennis in summer and football in winter, thinking nothing of working in the paddocks on a Saturday morning, then riding kilometres to Wokurna to play football, staying for tea and a dance, then riding home.

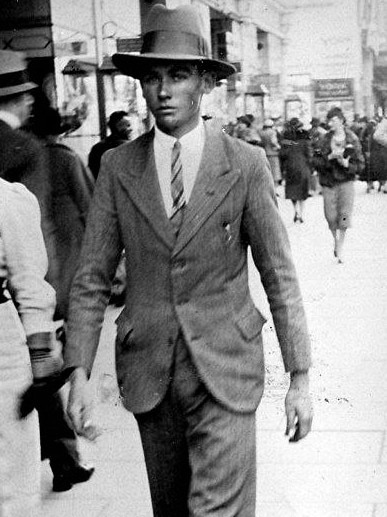

At the age of 19, Ed’s world changed forever when Australia became embroiled in World War II.

Fuelled by feelings of patriotism and duty, Ed said he had a strong urge to join up but resisted it for a while, until 10 of his footy mates from the surrounding districts of Mundoora, Wokurna and Port Broughton decided to catch the train to Adelaide to front up for enlistment at Wayville. During the medical, Ed’s inability to produce a urine sample on demand delayed his induction, which separated him from his mates.

As fate would have it, this delay later proved an advantage.

Most of his mates were drafted in the 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion which saw action in the Middle East and then was shipped to Java, where most were captured by the Japanese and endured atrocious conditions as prisoners of war for the remainder of the conflict.

After three months of intensive drill and weapons training, Ed found himself aboard the Mauritania, part of a convoy of troop ships carrying reinforcements sailing from Melbourne in November 1940, bound for the Middle East to join the South Australian 2/27th Infantry Battalion AIF.

It was a month before Ed’s 21st birthday. He would not see home again until March 1942.

On shore leave in Perth, Ed was struck by the comments of an old digger who had seen action in World War I: “You buggers are mad, I wouldn’t be in it again if they were using tennis balls.”

Back on board, the men were issued with British Army clothing and equipment, “some of which was strange and some quite hilarious”.

“The items of most interest were the dual-purpose trousers known as Bombay Bloomers, with wide legs long enough to tuck in socks and theoretically, protect our legs from mosquitoes and other insects,” Ed said.

“They could also be worn as shorts by folding up the leg of the pants and securing it with a button each side.”

The men had their heads shaved before crossing the Equator and were issued with steel helmets, the weight of which initially made it hard to balance them on their heads. But the value of the helmets became apparent when the shrapnel started flying, Ed said.

India was the next port of call, where the fresh troops were put through intensive military training for some weeks at Deolali Camp, located in the hills outside Bombay (Mumbai).

The convoy left Bombay and passed through the Suez Canal to El Qantara, from where they were taken to Julis Camp, one of the biggest Australian army camps in Palestine, to join up with their battalion.

“We were told that we would have to get fit quickly as the battalion was capable of marching 25 miles (40km) a day in battle kit,” Ed said.

The men were posted to various companies. Ed’s platoon commander was Lieutenant A.J. Lee, who later won the Military Cross (and Bar), rose to the rank of Brigadier and, at war’s end, was elected as national president of the RSL.

Young and fit, Ed was made a runner – a critical and responsible job. Despite the advent of radio, a runner was often the only effective means of communication in the field between platoons and Battalion Headquarters.

When the company was on the move, laying phone wire was impractical and the few radio sets available, which were heavy, were only used for communication between companies and HQ.

Enduring sandstorms and flea-infested dugouts, being strafed by enemy aircraft while travelling in a 10-mile-long (16km) convoy during the invasion of Syria, and fighting French Foreign Legion infantry led by Vichy French officers, the 2/27th Battalion served with distinction, fighting over rocky, mountainous country, paving the way for the Allied occupation of Beirut.

The Syria Campaign only took six weeks, but Ed, like so many of his comrades, began it as a virgin soldier and ended it as an experienced campaigner. The men had tasted victory, but it would not prepare them for the deprivations and torments of the Kokoda Track in New Guinea.

In January 1942, the 2/27th Battalion was on the move again, first taken by truck to Suez and after much “organised delay” finding themselves on board the cruise liner Ile de France which sailed on January 30, 1942, bound for Bombay, where they were transferred to an ageing rust bucket, The City of London, which sailed in convoy with eight other ramshackle ships, bound for parts unknown.

The destination was first thought to be Burma (Myanmar), then Java, but when the Japanese took Java and Singapore, the convoy was diverted to Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

There they were greeted with the best news of all – they would sail for Australia to help defend the homeland.

Ed and the rest of the 2/27th Battalion arrived at Port Adelaide on March 25, 1942, but their stay in South Australia was short.

Transferred to Springbank Camp opposite the Repat Hospital on Dawes Rd, the men were issued a week’s leave, not long after which they were first transferred to Glen Innes in northern NSW and then to Caloundra in Queensland to train for jungle warfare in the rainforest.

But nothing could prepare them for the energy-sapping humidity, the impossibly steep, muddy tracks and the tangled wall of rampant rainforest with which they would be confronted in the Owen Stanley Ranges of New Guinea.

Nor had they faced a suicidal, desperate enemy.

Five months after setting foot back on home soil, Ed and his comrades in the 2/27th Battalion were again bound for parts unknown.

In August 1942, the battalion sailed from Brisbane to New Guinea. As the troop ship moved through the listless, oily waters of Port Moresby, the horizon was filled with rugged, jungle-clad mountains.

The Japanese Imperial Army had landed on the north coast of Papua and were advancing across the Owen Stanley Range down a little-known native trail in a bid to take Port Moresby, from where it could stage air attacks on Allied shipping and mainland Australia.

The 2/27th Battalion and its 7th Division sister battalions, the 2/14th Battalion from Victoria and Western Australia’s 2/16th Battalion, were sent to help stop the advance and turn the Japanese back in what would become known as the Kokoda Campaign.

The only route of advance was up the 96km-long Kokoda Track on foot.

The men’s kit was limited to half a blanket and a change of clothesso they could carry more rations and ammunition and as they scrambled up and down impossibly steep slopes, hour after hour in the heat and suffocating humidity, many a country lad must have rued the day they caught the train to Adelaide to sign up.

Slipping and sliding in the mud, they often made slow, agonising progress, sometimes alleviated by the advance work of army engineers who had laboured ahead of them, chopping out footholds on some of the steep inclines and bracing them with small logs held in place with wooden stakes to create stairs.

It was tough going and any soldier aged over 35 who was not fully fit was left out of the initial advance up the track.

The campaign was beset with problems. The supply of food and ammunition was sporadic, with US DC3 cargo planes flying in low through the valleys and over razorback ridges in attempts to accurately drop cargoes of bully beef and biscuits through the jungle canopy to the troops.

On the ground, the cry went up to take cover behind trees whenever the soldiers heard the engine drone of looming aircraft, to avoid being hit by bales of rations and ammunition wrapped up in blankets, some of which burst open on impact, spreading their contents over a wide area. The soldiers had to hunt, first for the impact site which might be more than a kilometre away, and then through the wreckage to find intact food and equipment.

One poor young bloke, one of the battalion’s first casualties on the Kokoda Track, was killed when a tin of falling biscuits hit him on the head.

Soldiers also died when they tried to fire mortar bombs which had been made faulty by the impact of cargo drops. In the heat of battle, as the soldiers attempted to launch a mortar attack, damaged detonators in the bombs made them explode in their faces.

Communication also was a major problem. With the track often only wide enough for one soldier at a time, in some places made a muddy wallow by the tramping of thousands of boots, the advancing battalions were strung out over kilometres. With the men on the move, laying phone line was pointless and the rugged terrain limited any radio use.

“Any message to go forward was passed orally from man to man, each puffing and gasping as he climbed,” Ed said.

The 39th Battalion, made up of young, inexperienced militia men, had bravely delayed the advancing Japanese for some weeks, sustaining heavy casualties.

The 7th Division’s 2/14th and 2/16th Battalions were sent up the track to support and relieve the 39th Battalion. Badly mauled, they pulled back to make another stand at the village of Efogi while simultaneously, the 2/27th Battalion, held in reserve, was rushed forward.

On September 6, 1942, bolstered by the arrival of the 2/27th Battalion troops, who had desperately scrambled up the track in the preceding 48 hours to support their mates, they made another stand.

The soldiers of the battle-weary 39th and 2/14th Battalions moved through the 2/27th Battalion as its men frantically hacked out trenches from the rocky ground with whatever they could find – tin hats and bayonets – digging in on a razorback mountain spine overlooking Efogi which would come to be known as Mission Ridge. Little more than a kilometre up the ridge, headquarters was established at a knoll called Brigade Hill, later known as “Butcher’s Hill” where the tired men of the 2/16th assumed positions as reserve for the 2/27th Battalion, while the bedraggled soldiers of the 39th and 2/14th Battalions moved on down the track to relative safety.

“Our position was part way down a long forward slope which fell away more steeply in front of us,” Ed said.

“A Company was on the right of the track and B Company (my company) was on the left.”

Air support was called in and the men waiting in the trenches as dawn broke watched as low-flying American Airforce P-39 Airacobra fighters roared down the valley towards Efogi, strafing and bombing the Japanese placements.

For a few minutes the heavy, humid air was saturated with the reek of hot engines and aviation fuel.

To the soldiers on the ridge waiting tensely in the trenches, the smell was sweet.

Then the Japanese opened fire with their mountain guns, the disassembled parts of which they had hauled down the track from the coast.

“The Japs hammered at us all day from first light, a very long day without relief in the very hot sun,” Ed said.

“We were out of food and water and had little chance of replenishment.”

The effect of the mountain guns on the Australian soldiers was devastating.

When forward patrols passed through Mission Ridge a few weeks later as they chased the Japanese back to the north coast, they found bodies blown up into tree branches.

The Japanese had ranged their artillery shells to explode on impact as they hit the tree canopy, sending waves of shrapnel scything through the undergrowth.

Bodies of men who had dug in amid tree roots were found with their skulls cracked open like eggshells, the result of the percussion of the blast being carried to the ground through the trunk.

“The attacks eased off as night fell but resumed at first light the next day,” Ed said.

The events of that day were etched in Ed’s memory.

A fellow soldier in a nearby forward trench stood up quickly to throw a grenade but dropped it as he pulled the pin.

The impact of the explosion on the three men in the confines of the trench was horrific.

Two soldiers died outright, but one, in the last minutes of his life as his blood seeped into the soil, called out to Ed by name to come and “finish me off”.

Pinned down and the last man left in his section, Ed furtively watched the jungle for signs of enemy movement as he listened to the soldier’s plaintive cries weaken and then fall silent.

A little later, Ed saw Japanese riflemen move past a gap in the undergrowth and fired off a few rounds. Now they knew his position.

“I heard movement in the grass in front of, but out of sight of, my position so I took a grenade out of my utility pouch and was about to pull the pin when a bullet came through the top of the mound of earth in front of me and struck the fingers of my left hand, which held the grenade,” Ed said.

“The fact that the bullet had lost velocity by passing through the earth mound obviously saved me, as the grenade, which at the time was just in front of my navel, did not explode.

“I have only told that story to a few people, as I feel they would probably consider it a tall story without any proof.”

The ricocheting bullet took off the top of Ed’s finger. He picked up the grenade and managed to pull the pin and throw it.

Then he slipped out in the long grass “like a goanna” and made his way back to platoon headquarters where he had the wound dressed and was ordered to move out with the walking wounded.

“I offered to stay but was told I would be a liability …” Ed said.

To add insult to injury, an officer asked if the missing finger top was an SIW (self-inflicted wound).

SIWs were used by soldiers to get out of the firing line. But anybody who knew Ed knew that it was not something he would do.

That evening, the remainder of the 2/27th Battalion,300-odd men, retreated off the Kokoda Track and, carrying their wounded, began a two-week trek through the jungle to make it back to the safety of the Australian lines.

Ed spent a week at base hospital, where he lost the end of one mangled finger and had another stitched up, before returning to active duty.

A few months later, he was back in action at Gona on the north coast of then Papua, where the Japanese, hidden in bunkers, were desperately holding on for reinforcements that never came.

“The attack went in at first light,” Ed said.

“We were held up by enemy in heavily fortified positions. We were stopped and losing chaps right and left and I made the mistake of picking up a dead soldier’s Bren light machine gun that was lying on the ground.

“It was a sticky position and just a matter of time before I copped something as I could see bullet holes appearing in the leaves of the pandanus palm behind which I was concealed.

“I was firing through the foliage in a standing position. The Japs must have thought I would have had enough sense to be in a lying position, because when I did stop one (a bullet) it went through my left foot, just below the ankle, splitting the heel bone on exit.

“I gave the game away then and slithered back through the undergrowth, got bandaged up and put on a stretcher, then carried several miles by native carriers before being placed on a transport plane and evacuated to Port Moresby.”

With his leg and foot in plaster, Ed was taken by hospital ship to Brisbane, then to a hospital in Baulkam Hills in NSW where, within 24 hours he fell ill with malaria. By the time he recovered, his foot was out of plaster, but he took some time to learn to walk again without a limp.

Ed was back in New Guinea in August 1943, marching north through the Markham and Ramu Valleys in the campaign to take Lae, and engaged in the attacks on Shaggy Ridge in the Finisterre Ranges.

By this time Ed was a Sergeant and, after falling sick and being moved to Port Moresby to recuperate, was told by his commanding officer that he had been recommended to attend the Officer Cadet Training Unit at Woodside in South Australia.

He passed and was made a Lieutenant, then sent to the Jungle Warfare Training Centre at Canungra in Queensland where he instructed platoons of 30-odd young recruits.

Ed was posted to the 31/51st Infantry Battalion and in late 1944 found himself again in the jungle fighting the Japanese, this time on the island of Bougainville.

He was discharged two weeks before his 26th birthday and, given that he had served in the army for nearly six years, admitted that he “found camp life almost enjoyable, with regular meals and exercise and plenty of activity, being fully occupied with the tasks in hand”.

He also enjoyed the camaraderie and humour.

Ed remembered one incident in which a larrikin sent a burning wad of newspaper floating down the water trough of a latrine block.

There were ten toilets in a row and as the burning paper passed below each occupied seat “the incumbents rose rapidly from their throne in succession, their placid expressions changing to one of consternation as they turned, clutching their trousers at half-mast to peer into the latrine to ascertain the cause of the heat”.

The larrikin got away.

Ed applied the same enthusiasm he was noted for in the army on his return to civilian life, first joining the RSL in Port Broughton and, in 1948, transferring his membership to Bute.

He held various positions at the Bute RSL including President (1953, ’78, ’79, ’87, ’90, ’91, ’92, ’93); Secretary (1982, ’83, ’95); Treasurer (1961, ’62, ’97), Vice President, Assistant Secretary and was elected a State Councillor in 1964.

Ed was appointed Local Controller of Civil Defence in 1963 by the District Council and for his service, was awarded the National Medal in 1989.

He was the last President of the Wokurna Football Club and the first president for the merged Mundoora/Wokurna club in 1966, and in 1972 was elected President of the Broughton Football League following three years’ service as Vice President.

In 1989, at the age of 69, he received the Australia Day Citizen Award, and in 1990 was awarded the Order of Australia Medal (OAM) for his service to community, and made a Life Member of the RSL.

South Australian soldier Ed Ebsary – October 15, 1919-January 13, 2022 – is survived by four children, two stepchildren, 16 grandchildren and 24 great-grandchildren.

“In retrospect, I believe I have had an interesting life, during which I have naturally made mistakes, but I have done nothing of which I should be ashamed,” Ed once said.

“Embarrassed yes, but not ashamed.” ■

Edgar James Ebsary OAM / 1919–2022