Human rights activist Khadija Gbla shares insight into later-in-life autism diagnosis

Khadija Gbla is one of a rise in young females being diagnosed with autism in Australia. Here they share how that diagnosis has changed their life.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

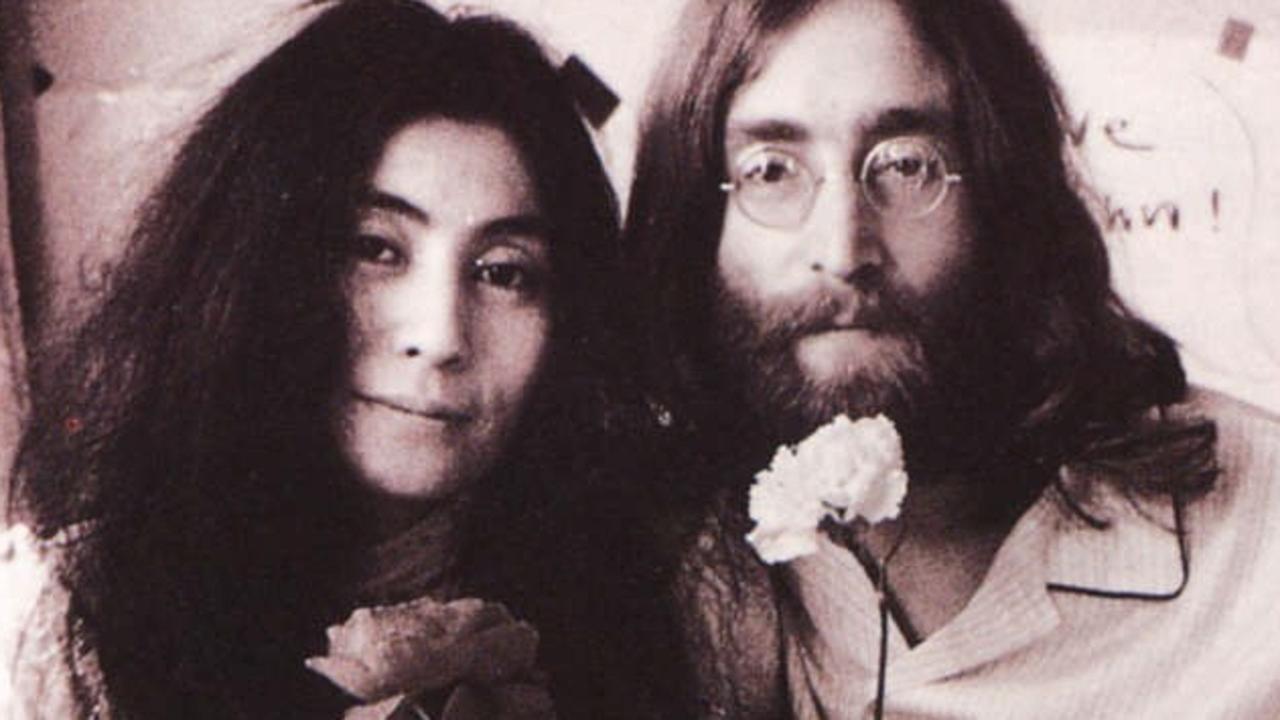

Khadija Gbla had spent their whole life wondering why they felt different. On the outside, Khadija appears to have this larger-than-life personality, unquestionably confident and has even built up a career as a human-rights activist who regularly presents big ideas to big rooms of people.

But inside, there was often a feeling of being totally overwhelmed, especially in social situations, a feeling of deflation when completing everyday tasks took much longer than others, and sensory and food issues.

It wasn’t until two years ago, when Khadija was 34, that things finally clicked. Their son, Sammy, was diagnosed with autism and ADHD and for the mum-of-one, it was like a mirror being held up and they saw themself for the first time. “I sat there and thought: if Sammy’s like me, and he had reminded me this whole time of myself, is it possible that I am like him?” Khadija tells SA Weekend.

Khadija, who was born in Sierra Leone but moved to Australia with their family as a refugee at 13, sat down and wrote a list of all the things they had in common with Sammy. When they looked at the list, they decided it was time to get a diagnosis.

“(With my diagnosis) I found out I was normal. There was nothing wrong with me, I just didn’t have the support I needed,” Khadija says. “It was always an uphill battle and now for the first time, I know who I am.”

Khadija, now 36, born female but identifying as non-binary and femme-presenting, is hardly alone in their later-in-life diagnosis. Globally, more and more women are being diagnosed with autism, a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by social and communication difficulties that has long been associated with boys.

There are two reasons why females have generally slipped through the cracks. Autism and ADHD often present differently in females than in boys and can often be more internalised and harder to spot. And females are also better at a coping mechanism called masking. Khadija admits that, growing up, topics like autism were considered taboo so they would “mask” to hide their autistic traits and appear “normal” to blend in and avoid discrimination, which is a common “survival method” for many autistic people.

“I wouldn’t have known I was autistic. Being a black, African, refugee settled in Adelaide, topics like autism and ADHD aren’t even spoken about,” Khadija says.

Khadija, who also has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome which causes severe pain and makes their joints prone to dislocation, adds that there’s a “stigma” in their community when it comes to both physical and mental conditions.

“I came here with a refugee mum who thought if bombs are not dropping everywhere, nobody’s trying to kill you – I have no time for you to be disabled, that’s what she said,” Khadija adds. “You’re a girl, you’re black, you don’t need to add anything else to that. So being raised that way I masked my whole life, I was taught how to mask.

“In part of my community there’s a stigma, the idea that you’re cursed. My mum wasn’t ashamed so much that I was disabled, she was afraid that others would judge her for having an imperfect child which to her would be a reflection that she did something wrong.”

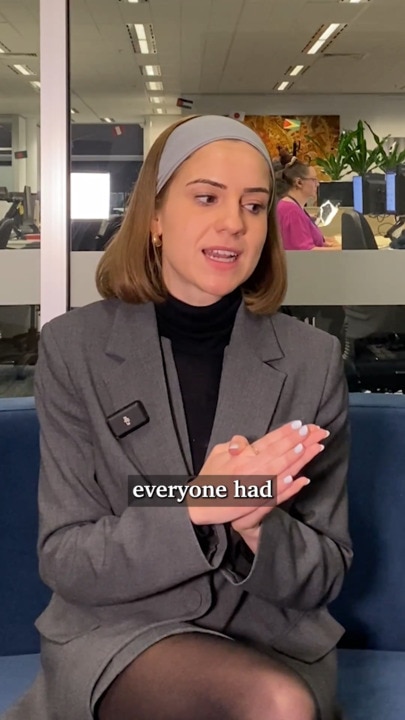

Like Khadija, many don’t realise they’re autistic until their kids are diagnosed, Adelaide-based speech pathologist and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnostician Amelia Griffin explains. Griffin works with clients of all ages and has diagnosed many adults that have come in after their children had been diagnosed, including a 72-year-old woman.

“Her child was diagnosed as a teenager, and it took years before she came in for a diagnostic, but she definitely started to see similar traits and challenges,” Griffin says.

She admits that being diagnosed was like finding a missing puzzle piece for her client who had spent her life feeling like an outsider.

“She felt like everyone had a rule book on life, and she missed out on a copy, so she didn’t understand how everyone else had all this information and knowledge about life and communication and friendships, and she didn’t have that,” Griffin says. “So for her, it was a validating experience, and she was just really elated to have been heard.”

Noticing a lack of age-appropriate therapy apps for adults, Griffin has gone on to create My Mind Matters Therapy, apps designed to enhance communication, memory, and attention skills that are “very common challenges with the autistic brain”.

“I have a lot of adult clients, and that’s something that’s very frustrating for them, because they either have to use apps or programs that are created for children, or they don’t use it at all.”

Launched in May, the augmentative and alternative communication (ACC) app’s features include predictive text to speech using emojis, text picture exchange communication, audio and voice recordings to “help people with complex and different needs communicate more effectively.”

While her language-based brain training app focuses on improving memory, attention, listening skills and comprehension through recall simulation exercises like job interviews, phone conversations and remembering people’s names and faces.

Autism diagnosis in Australia is increasing, and that’s largely down to a rise in women sharing their diagnosis on social media.

At last count, a little short of 140 million videos with the hashtag #girlswithautism had been posted on TikTok alone.

And in March 2024, Bruce Willis and Demi Moore’s daughter Tallulah, 30, recently shared her own diagnosis.

But there are still women falling through the cracks. An Australian-first study from Flinders University last year found that current diagnostic tools are designed to detect autism in males, who present differently to females, making it difficult to diagnose females with autism.

The study’s co-author Professor Robyn Young found that autistic girls and women typically aren’t diagnosed until adulthood, if at all, meaning they spend years without support.

“There’s two reasons why this might happen.

“Girls seem to have better pretend play and therefore learn the skills of mimicry quite early and girls are also often socialised differently,” Young says.

“So girls tend to mimic and camouflage, but also the autism presents differently.

“When the original diagnostic criteria was first introduced, the predominant sample we were looking at was young males. So we’ve got this male centric view of what autism looks like, and the criteria hasn’t been adjusted.

“And compounded with that is that people are often primed to think about autism in male conditions, and don’t often think about it in females, and then when they present with co-occurring conditions, such as an eating disorder or anxiety or depression, that might take centre stage, and the autism is overlooked.”

Young’s research has been instrumental in improving early detection methods, creating the Autism Detection in Early Childhood (ADEC) screening tool during the pandemic which is now used across the world.

“If the diagnosis is given earlier, children can be given the appropriate support that they might require,” she says. “So, for example, if they are unable to communicate or have language deficits, they might engage in speech therapy.

“If part of their condition is sensory sensitivities, they might engage with an occupational therapist to help them manage their environment better, or for other people to accommodate their needs better.”

There are three support levels indicated with an autism diagnosis, ranging from mild to severe. However this level is only a snapshot in time and can change multiple times throughout a person’s life.

Prior to being diagnosed, Khadija had never seen another autistic person of colour, highlighting the need for diverse, female representation.

“I stopped myself from accepting that I was (autistic) because I thought I don’t behave this way, I don’t behave that way because society shows us a very stereotypical type of autism,” they explain.

“It’s a white boy who was diagnosed, like a Sheldon Cooper(a character in TV series Big Bang Theory whose behaviour is consistent with autism), very amazing at maths and science and everyone then can love them but very socially not aware.

“I am outgoing, I like actual people, I am an extrovert – that’s part of my Africaness – so I thought maybe I’m not, I couldn’t be and that’s very common.”

In June, the state government launched SA’s first state Autism Strategy, a five-year “roadmap” to help improve the lives of autistic people and their families by improving access to diagnosis, essential support and services, and promoting inclusivity.

While there’s still a long way to go, Autism SA Clinical, Care and Community executive manager Becca Morton says it is a step in the right direction.

With more than 20,000 registered individuals on the autism spectrum, Autism SA is dedicated to supporting autistic South Australians through advocacy and education.

“As well as providing support we focus on advocacy, both at a structural and community level and lots of education around what autism is, and supporting businesses and organisations with being autism friendly and thinking about neurodiversity affirming practices, and helping people understand,” Morton says.

But most importantly, they work to challenge people’s misconceptions of autism and its limitations.

“One of the best things about what we do is that ‘aha moment’ of challenging people’s thinking when they say we can’t do this because they’re autistic,” she explains. “Years ago, I worked on our info line, and a school called up and were like: ‘We’re going to the Botanical Gardens, but we don’t think little Johnny can come because he really loves to put leaves in his mouth. He’s a sensory seeker, he’s always out there sticking leaves in his mouth and if he does that there, he’s going to put something in his mouth that’s poisonous.’

“Their risk assessment was that we have to exclude him from this trip, and I was like, there are ways around this. We’ve got to get creative. I asked if there were any particular leaves he liked.

“They said he likes them to be really green and soft, so I asked have we thought about mixed leaf lettuce? What if we had a bag of mixed leaf lettuce in his pocket for him when he feels the urge?

“I got a phone call back from them the next week to say he went, it worked, it was brilliant, he was happy with his bag of lettuce. Everyone’s happy and there was no exclusion, it was just a bit of an adjustment.

“There is a lot of focus on how do we stop this? But do we need to? No, we don’t unless it’s a danger for them or those around them. We just have to make sure they do it in a safe way.”

Khadija has dedicated their life to breaking down similar barriers, including harmful generational patterns, starting with Sammy, aged nine.

“His diagnosis was a chance to do things differently and I am proud and happy I chose the path of acceptance,” they say. “I am also hopeful (for the future) because we are raising a generation of kids who don’t have to mask. My son doesn’t know how to mask because his reality is being his authentic, unmasked self and I think that’s a gift. Everyday he sees a version of himself reflected back to him (through me) and he says it makes him feel normal, ‘because, mummy, you understand me’.

“I find myself sometimes being jealous of him. I go, ‘Oh, I’m so jealous, I wish I had the mummy you have.’ But I am mummying that part of me. I am reparenting little Khadija, so everything I give Sammy, I give myself.”