The Parwana story: How the Ayubi family fled Afghanistan and created an acclaimed restaurant in Adelaide

When a border official turned a blind eye to a young family fleeing Afghanistan 35 years ago, he set in motion a turn of events that would ultimately create an Adelaide culinary institution.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- From Afghan war crimes investigator to Captain Cricket

- More great reading in SAWeekend

- Brainwaves: Test your general knowledge

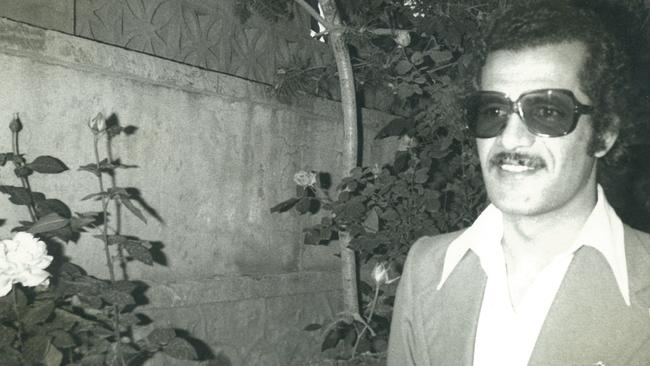

Farida and Zelmai Ayubi stood nervously with their four young children opposite the border official in Torkham, the major town crossing between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

It was 1985, and the family was fleeing their increasingly unsafe home of Afghanistan in the height of the Soviet-Afghan war.

Their way out was a crumpled piece of paper that stated they needed to enter Pakistan for a family wedding – a wedding that didn’t exist.

But there was a discrepancy with the dates on the paper, and the official noticed.

“My heart fell, and my legs started shaking,” says father Zelmai, then 38 and now 73.

“Not (that) I worry for myself, but my children. (My daughter) Durkhanai was nearly one-year-old …”

In what was either an incredible stroke of luck or divine mercy – perhaps both – the family was spared.

“He said, ‘Give me your hand’, and he marked my hand,” Zelmai says.

“He told me, ‘Go. I know you have no wedding; I know you are not coming back. Take your wife and your children and go, and I wish you a happy life’.”

That was the first step of a life-changing journey for the Ayubis, now a family of seven and the heart of award-winning and internationally recognised Adelaide suburban restaurant, Parwana.

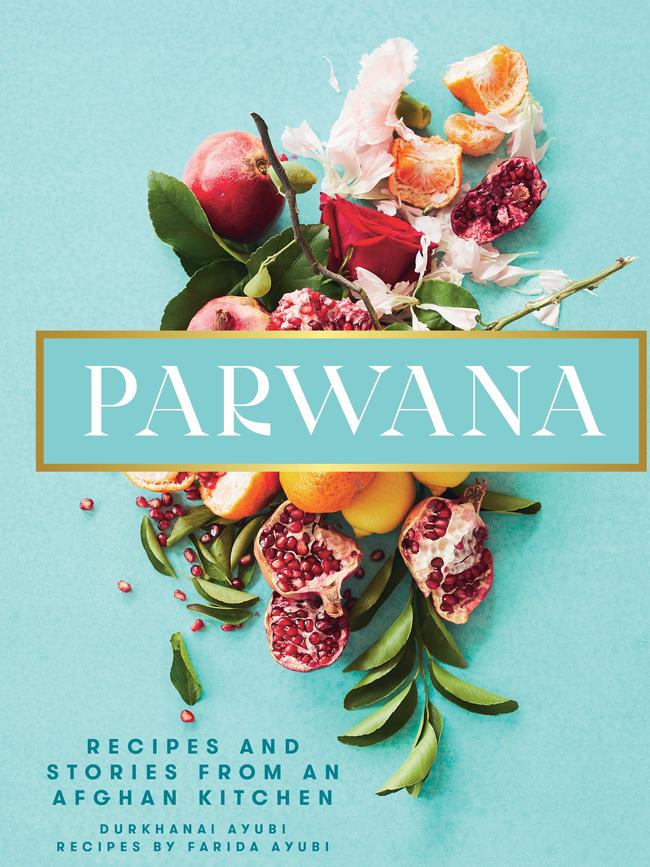

Their story is told in a new book, penned by Durkhanai Ayubi – the fourth daughter and the baby who was taken across the border. The book, also titled Parwana, meaning butterfly, bundles her mother’s prized recipes with a detailed history of Afghanistan. It’s a history that reaches far beyond the recent “war on terror”, one that Durkhanai deeply believes has been erased to the detriment of all civilisation.

“Our narratives about humans and different countries, and the way history has developed has been eclipsed by violence … and Islamophobia,” Durkhanai, 35, says. “But, to me, that history is the past 40-50 years – that’s like the blink of an eye.”

I’m speaking with Durkhanai and her parents in the eclectic dining room of Parwana, on Henley Beach Road in Torrensville. There is colour at every turn, from the walls painted pink and blue, to the mismatched geometric floor tiles and turquoise chairs. It’s a far cry from the barren landscapes and confronting visions of war in Afghanistan we see on TV.

“Nobody knows Afghanistan other than through a lens of violence and terrorism,” she says.

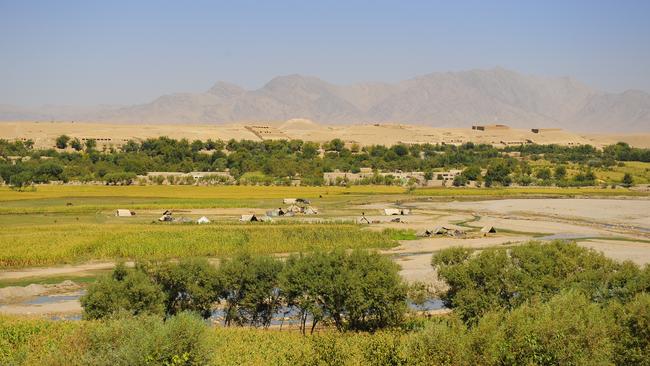

Yet Afghanistan wasn’t always synonymous with war. Google “Afghanistan landscapes” and you will likely be stunned by what you see. Mighty, snow-capped mountains. Lush, fertile valleys. Even Durkhanai was surprised by this when she returned to her birthplace with her sisters in 2012. Of course, by then, those picturesque views were juxtaposed with crumbling buildings, overcrowded living quarters and army tanks rolling through the streets.

“You’ve got this beautiful landscape that is pristine in many ways, then you see how humans can destroy that,” she says.

Family matriarch and the restaurant’s celebrated cook, Farida, now 64, likens Afghanistan’s beauty to that of Australia and Europe. But the atmosphere, the culture, the people, has all been displaced.

“Sometimes when I think about it, it makes me really, really sad, because everything gone,” says Farida.

“It is very hard, especially because I saw everything – I was in the golden time of Afghanistan when I was raised. How beautiful (it was).”

Farida is softly spoken but her smile, sometimes hidden in photographs, is infectious. Her husband Zelmai, on the other hand, is louder both in speech and dress. Today, he is sporting a vibrant patterned shirt, something of a trademark for the former lawyer. But the two of them radiate warmth and exude a sense of hospitality – and this is the cornerstone of Parwana.

The history of Afghanistan, a landlocked country in south-central Asia, is long and complex. In first century BC, it was at the centre of the ancient Silk Roads – an important network of trade routes that spanned key centres from China to Rome, India and Siberia, allowing the exchange of goods such as textiles, spices and precious metals, as well as ideas.

Afghanistan was wealthier for it. Various empires and political movements helped shape the country over time and the book delves deep into all that history, thanks to Durkhanai’s two year’s of research and writing. Contrary to recent events, it wasn’t long ago that things were looking promising for Afghanistan. The 1964 constitution looked to modernise the country, introducing women’s rights and open education.

“Then all sorts of twists and turns happened,” Durkhanai says. “Eventually what happened was a series of ideologies that is completely foreign to Afghanistan and its people – whether it was communism of the Soviet era, and then the fundamental Islam that emerges because of that … all of those things were so foreign to generations like my parents’.”

The Soviet invasion of 1979, which marked the start of a nine-year war between the two countries, was a major catalyst of Afghanistan’s downward spiral.

“The biggest thing … very early on is the intellectual and spiritual and cultural exile that happens because of war and violence,” Durkhanai says. “The culture and traditions of the nation collapse.”

Farida adds: “Good people, educated people – they (were) gone in two years.”

The Ayubis’ arrival in Pakistan in 1985 was not the end of their turmoil.

“The life for refugees, Afghan refugees, in Iran and Pakistan and Europe, they have very hard life,” Zelmai says. “In Pakistan we were not safe. We had no safety. The refugees have no freedom … everywhere we go there is fear.”

“Everywhere fear,” Farida adds. “In the middle of the night, like in Afghanistan, when you hear a car stop out there you’re thinking: ‘Somebody is coming to take him (Zelmai) to the jail, or take him to kill him’. All the time.” To say Zelmai was lucky to survive his later years in the Afghan capital of Kabul and then Pakistan is an understatement.

The family was Muslim, but not part of any Islamic party that had evolved in the fight against communism. Men who refused to join Islamic groups would either be killed, or go missing.

“We had more enemies than friends,” Zelmai says. “I was an easy target – they could say false things about me to make me in trouble. I was very, very lucky. Thank God, they didn’t capture me.”

The family’s lifesaving migration to Australia was made possible thanks to an old family friend, Dr Nouria Salehi, who moved to Australia in 1981 and, while working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, was helping resettle Afghan families in Australia.

It was by chance that Zelmai saw Salehi’s father in Pakistan’s capital Peshawar, just as he was preparing to leave for Australia. Zelmai was able to pass on his family’s names and dates of birth for Salehi, so that she could organise a sponsor for the family.

Plans to leave Pakistan had to be made quietly, Durkhanai explains in her book. “Once a week, in the early hours of the morning so he wouldn’t be seen, my father would make his way over to the (Australian) embassy quarter,” she writes. After some time, Zelmai finally received the news he’d prayed for. His family had been accepted as migrants to Australia.

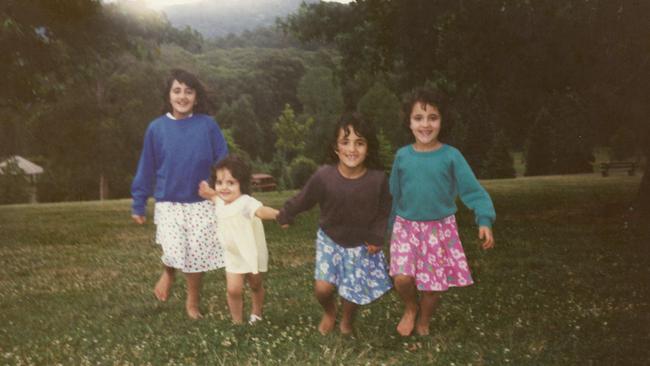

Zelmai, Farida and their four daughters – Fatema, who was now 11, Zelaikhah, 7, Zahra, 5, and Durkhanai, 2 – landed in Melbourne in 1987. “We got freedom!” Zelmai exclaims. “We got safe place for my children; for us. We had very hard life, but I pushed my children to study, to learn.”

The family spent their first two years finding their feet in a new country, but found Melbourne a little overwhelming.

A friend from Afghanistan was moving to Adelaide, and they decided to follow. Setting roots in Edwardstown, they truly began to feel at ease. The children enrolled in the local primary school, and Durkhanai would go to childcare while Farida and Zelmai caught the tram to English lessons. Zelmai’s law qualifications were invalid in Australia, so he took up odd jobs while Farida, a primary school teacher in Afghanistan, took care of the children. In 1994, the couple’s fifth daughter, Raihanah, was born.

While the family was relieved, and grateful, to be living in Australia, there was a yearning to preserve their culture.

“For us, living in Australia as a diaspora community, my mum’s intuition was really strong about holding onto those traditions, and, for Afghans, food and hospitality is a massive part of how we express the cultural identity,” Durkhanai says.

Farida always loved cooking, and everyone loved Farida’s food. “When God gives you food, you should share it,” Farida says. “That’s the important thing we learn from my dad and family: always share.”

The natural cook began catering local events and weddings, and soon word spread outside of the local community and demand picked up. Eventually, Farida thought a “little restaurant” might be worth a try – if nothing else, it would serve as a useful kitchen for her catering. In 2009, the family opened the doors to Parwana Afghan Kitchen.

“Of course in the beginning it was very hard,” Farida says. But those who chanced upon the restaurant embraced it. Then came the positive reviews – the first from local food writer Ann Oliver, just a month after the restaurant opened.

“Every now and again you stumble across an establishment that is really good, and virtually unknown,” she wrote. “Farida weaves something magical in her kitchen.

“The bolani, the wafer thin crispy leek filled bread and yoghurt dip, was divine, uncomplicated delicious perfection.” The ashak, a style of dumpling, were described as “scrumptious”, and the narenj palaw (orange rind rice) “gorgeous”.

Later in the piece, she predicts the Ayubis would become a celebrated food family, much like the Singhs, of Jasmin fame. How right she was.

Next came The Advertiser’s Simon Wilkinson, who would include the restaurant in The Advertiser Food Guide for years to come. In his reviews, he describes the mantu dumplings as “heavenly”, cloaked in “just the right amount” of lamb mince, yoghurt and paprika; the banjaan borani (eggplant) as an “unctuous sludge that even the avowed eggplant hater among us scrapes up with glee”, and the palaw (rice) as the “Ginger Rogers to the eggplant’s Fred Astaire, each grain so perfectly light and tender you could almost imagine them dancing across the plate”. “The Kabuli version is topped with threads of carrot, sultanas and almonds,” he writes. “If there is better rice anywhere, please let me know.”

“It just kind of took off,” Durkhanai says of the restaurant. “I noticed a shift after the five-year mark, and then it expanded on another level again.”

In 2014, the family opened city offshoot, Kutchi – meaning nomad – with an approachable lunch menu that reached a whole new demographic. Then, in 2018, the main restaurant expanded to offer an extra dining room. Parwana now accommodates 200 people over two sittings per night, six nights a week. And, still, it remains one of very few suburban restaurants to require an advance booking.

Parwana’s most recent achievement was an unexpected, glowing review from The New York Times two years ago. But food critic, Besha Rodell, almost didn’t make it, unaware this was a restaurant that booked out, night after night. “There aren’t many high-demand reservations in the South Australian capital. But Parwana excels at many things, and defying expectations is one of them,” she wrote, having later returned to the restaurant with a booking. “The small storefront space has a striking aesthetic, one that is worthy of a design magazine but stays true to the history and culture of the family.”

The rice, Rodell describes, is Farida’s “greatest gift to the universe”. “It is not often that a dish as common as rice will knock me off my dinner chair, but the aged, long-grain narenj palaw at Parwana left me agog.”

Praise also goes to the meats slow-cooked in yoghurt and spices, and served with a “deep green herb chutney that tastes like photosynthesis splashed with lemon”.

The NYT review spiked interest but above all, “it felt really special”, Durkhanai says. “There’s recognition outside of the country for something we’re doing so locally, and that was really rewarding.”

For local fans of Parwana, praise for the eggplant simmered in tomato, the mantu dumplings blanketed with lamb kofta sauce and decorative kabuli palaw are not surprising. The food is, in the simplest sense, delicious. It’s also incredibly generous – you’re best to go with a group to share. After all, dining at Parwana is a celebration – the colours, the cultural cues, a friendly Zelmai working the floor, and the beautiful patterned plates that make even a humble curry look pretty. It’s BYO only, and corkage is donated to local charity. It’s among many reasons why Parwana has been awarded, and is repeatedly nominated for, Best Community Restaurant in The Advertiser Food Awards.

Dig a bit deeper, and you’ll see these dishes aren’t just a harmonious blend of textures and flavours, but also a culmination and celebration of cultures that met on the ancient Silk Road. From the spices of India, to the aromatic rosewater of the Middle East. Like an artist to canvas, Farida applies her ingredients with a deft hand, creating something so comforting yet so full of flavour. And it’s all done in a modest-sized kitchen, where oversized pots of curry simmer on the stove while dumplings are hand-folded, and plated dishes are drizzled with seasoned yoghurt.

Farida has no hesitation in sharing her recipes (although writing them down in teaspoons and cups did not come easy). For her, and the family, the book is the next step in preserving their culture. Durkhanai also hopes the book will encourage people to think more deeply when it comes to Afghanistan and other war-torn countries, and their people. Fellow refugees.

“We all have stories and we all have ancestries and connections,” she says. “To be a foreigner in a different land to where you’re born usually comes with a lot of grief and loss and misfortune.

“If people had a choice to be safe where they are, where they’re connected to their own history and ancestry, of course people would choose that.”

Afghanis just like the Ayubis have continued to seek refuge since the Soviet-Afghan War. Civil wars in Afghanistan ensued after the Soviets withdrawal in 89, towards the end of the Cold War era. Then, unforgettably, came the United States’ “war on terror” in the wake of the attacks by al-Qaeda on Washington and New York in September, 2001.

A Brown University paper released in September states that since the post-911 wars, at least 5.3 million people have been displaced from Afghanistan. Across Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya and Syria, this number rises to 37 million – more than those displaced by any war or disaster since the start of the 20th century except for World War II. And it’s a conservative number. It could be as high as 59 million – more than twice Australia’s population.

The Afghan community in South Australia is relatively small compared with the Greeks and Italians, who migrated earlier, but it has grown over time because of the ongoing waves of displacement. Afghanis find each other, through family, friends and active members in the community. “There are people … who do arts things, film festivals, and it’s all based on Afghanistan and its history,” Durkhanai says. “There’s a network of awareness.”

And while the restaurant, and the five daughters’ vocations, are keeping the Ayubis busy these days, those connections are always there.

The restaurant’s slogan reads: “At Parwana, we believe that even loss and suffering can forge beauty and generosity”.

For the Ayubis, their triumph has manifested into much more than a successful restaurant. Oldest daughter Fatema, now 44, has pursued her creativity in a patisserie offshoot, Shirni Parwana, which pops up at Plant 4 Bowden twice weekly. Zelaikhah, 40, now with three children of her own, is a forensic scientist. Zahra, 39, works for the Department of Human Services. Durkhanai is involved in the operations of Parwana and Kutchi Deli, while also a writer. And 26-year-old Raihanah has completed her law degree and is pursuing further study.

Five lives, five individuals who have flourished thanks to an improbable sequence of events that started with one border official who was willing to turn a blind eye to a fictitious travel paper.

Farida doesn’t plan on hanging up her apron anytime soon (“I love cooking. If you are successful and people are happy, why wouldn’t you love it?”) and calls Australia home. But she has hope for her homeland.

“How beautiful it would be if everybody could go and enjoy Afghanistan,” she says.

“Always hope is there. Nobody can win this sort of thing. They have to give up and they have to go to peace.”

Parwana by Durkhanai Ayubi; recipes by Farida Ayubi with assistance from Fatema Ayubi. Photography by Alicia Taylor. (Murdoch Books, RRP $45).