Tembel of boom: Our productivity tsar’s blueprint for SA

Adrian Tembel is sick of mediocrity. Now is South Australia’s chance to light the fuse out of Covid, he says. And he knows how we can get there.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The TV factory whistle called out across Adrian Tembel’s working-class Adelaide suburb twice daily, a metronomic constant of an industrial heartland that sustained thousands of families.

Born to refugees who fled the Soviet bloc after World War II, Tembel grew up in the city’s manufacturing belt – in a post-war, cream brick house on a large block in Seaton – about 9km northwest of the city’s CBD.

Tembel’s is a story of the child of a carpet layer and secretary, who grew up in a migrant neighbourhood and went to tough public schools nearby, before rising to the top echelons of Australia’s law profession by leading a top-10 firm, living with his family in one of Adelaide’s finest homes and becoming a key state economic adviser.

It’s also a narrative that reflects South Australia’s post-war propulsion into an industrial powerhouse, the pain of its subsequent decline and the lingering damage from the catastrophic 1991 State Bank collapse.

But Tembel’s rise from Seaton, along with his challenging mission to advise the Premier on how to rebuild SA as an innovative, prosperous powerhouse, offers hope and inspiration at a crucial turning point in the state’s history.

The Philips TV factory, whose whistle was the timer for Tembel’s childhood, was little more than one kilometre from his Russ Ave home. More than 2000 workers, mostly women, made TVs at a former war munitions factory at Hendon. Thousands more worked nearby in other factories. GMH produced cars in neighbouring Woodville, Australian Cotton Textile Industries’ (ACTIL) workers made sheets, pillowcases and linen on the other side of the railway tracks in the same suburb. At Woodville North, fridges were manufactured at a Kelvinator factory and Simpson Pope made whitegoods at Dudley Park.

“One of my first memories as a little boy was the opening and closing whistle at the Philips factory, about 4pm and early in the morning, and all the factory workers flooding in. Many of the families where I grew up were working in those factories, of course, growing up in the late ’70s and early ’80s,” recalls Tembel, 52.

But tariff cuts – initiated in the early 1970s by Gough Whitlam’s government, but continued by the Hawke and Keating governments in the 1980s and into the 1990s – were already starting to bite.

“Whitlam started cutting tariffs because he wanted to get, quite rightly, cheaper products into people’s hands, in Sydney, for example,” Tembel recalls.

“But we copped it. And all those factories – Philips closed, GMH and ACTIL at Woodville closed later – they all started to reduce. So one of the biggest memories as a kid was just unemployment. And it was dads mainly. I just remember in primary school and high school as well families just being adversely affected.

“I mean the morale, when your dad loses his job in that era, it’s not good. There was the early ’80s recession and then SA was going through this serious decline. In the northwest of Adelaide, we were experiencing it. We took the brunt of it, actually, that neighbourhood.

“It was ethnic families, working-class families and I have a very strong memory of that.”

Many of Tembel’s schoolmates were hit hard. He attended Seaton North Primary – future Labor state treasurer Kevin Foley was a decade ahead of Tembel at the same school and the common background has been a bond between them. Then Tembel went to Seaton High at the northern end of his street. In the early 1980s, Seaton was transitioning from being a boys’ tech school.

“We were full of wood workshops, plastics, metalwork. Those tech schools were built throughout Adelaide in the ’60s as a place to train young kids to go off and become apprentices or factory workers at 15,” he says.

“So there was no academic culture. I remember even in my era, in the early ’80s, there was 120 of us who started in Year 8 and then 12 of us were in Year 12. I think it was down to five who were doing matriculation, which is where you might have gone to university. I think three or four of us ended up going to uni. So it wasn’t academic.”

One field in which a young Tembel excelled was athletics. In 1982, the young 400m runner captained the SA boys’ Little Athletics team at the Hobart championships. “The feeling to represent our state was marvellous and I’m sure this helped our performances,” he wrote in the state association’s 1981-82 yearbook. Tembel went on as a high school and university student to represent the state in various national championship 400m finals, mixing with Australia’s best.

His professional career was inspired by two key influences – a childhood visit with his carpet-laying father to Adelaide establishment figure Kym Bonython mansion in the Hills, and his mother’s relentless determination that he and his brother get an education.

His father worked for well-known Adelaide firm Miller Anderson, based at a warehouse at Hindmarsh, in the city’s inner west.

“In his day, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, they’d cut the carpets to size and he’d head off into the big homes of Medindie, Unley Park and the Adelaide Hills and lay the carpets,” Tembel says. “As a little boy, I used to carry his bags sometimes and I used to see all these magnificent Adelaide homes and really lovely, polite, middle-class families. That was my first taste of how lovely that upper middle class life in Adelaide was.”

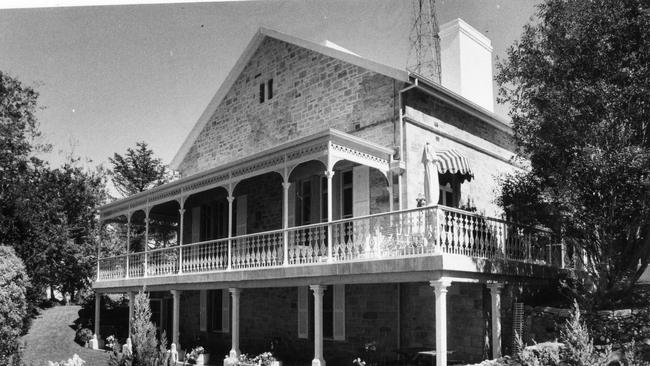

But the standout was visiting the Mount Lofty Summit Rd Bonython mansion, called Eurilla, before it was razed in the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires. “I remember as a little eight or nine year old, going there on a Saturday morning when my dad was laying the carpets. I looked at the lawn, the gardens and the home – there was this beautiful dog on the lawn with, I think it was Kym Bonython – I didn’t get to speak to him,” Tembel says. “And I thought – how amazing is that.”

While this provided something of an inspiration to get a strong education, it was not a matter of choice. His mother “drummed it into my brother and I” that it was “non-negotiable”.

“We had to get educated, which meant that we felt a bit weird in our environment because not many of the kids around us had those plans. So we felt a bit, you know, odd. The kids were messing around and not academic, but our mother was tough. And she wouldn’t compromise.”

Spurred to this path, Tembel studied economics and law at Adelaide University – drawn not by the prestige or earning capacity but because he craved a safe, comfortable existence.

Fresh out of university after graduating in 1993, though, Tembel’s fortunes were suddenly and inextricably entwined to the epoch of the State Bank collapse, a financial disaster that was publicly revealed in February, 1991. More than $3bn in government-guaranteed funds were lost. The fiscal cataclysm shattered and angered a state that, according to figures Tembel provides in his role as SA Productivity Commission chairman, remains saddled with the impact of a decade spent trying to restore its finances. But more of that later.

Back in 1993, the young graduate Tembel joined Thomson Simmons (as it was then known), a strong commercial law firm that had fallen on hard times. Its chairman, David Simmons, had been the State Bank chairman and was embroiled in a searching Royal Commission into its collapse. High interest rates and an early 1990s recession had been hammer blows to the economy and employment. A firm that had been strong in the 1980s was under severe pressure.

“I will always say, as will all my peers from law school who came out at the same time, it strengthened us, because coming out in such a deep recession where unemployment was high and getting a job was a privilege meant that when you joined the workforce, you were so happy if you got a job. Then you held on to that job with hard work. The firm I joined had a really strong work ethic. So, it was a double whammy of desperately trying to hold on to work, hold on to your job, and then a really strong work ethic,” Tembel recalls.

His rise to lead one of Australia’s top law firms, headquartered in Adelaide with over 130 partners and employing more than 560 people in all mainland state capitals, was catapulted forward by an early lucky break. Aged 24, Tembel connected with an Adelaide-based sports merchandising firm that was securing global Formula One Grand Prix contracts, particularly for the-then championship winning Williams team. “I got to deal intensely with some of the best entertainment lawyers in London, as a young Adelaide lawyer, and I copied them and learnt from them,” he says.

But while Tembel’s star was rising, having made partner in 1997, his firm’s continued to sink. By the time the Global Financial Crisis hit in 2008, the business was in deep trouble – profits sank, morale plunged and bank covenants were breached. Tembel was appointed chief executive partner in April, 2009 – his friend and colleague Loretta Reynolds had been appointed the firm’s chair in 2007.

The turnaround was nothing short of remarkable. Embarking on a continuing quest of mergers and acquisitions, they grew a business that is now Australia’s biggest law firm headquartered outside of Sydney or Melbourne. Revenues have grown from just under $40m annually to almost $200m.

“I think firms like ours are very important and the fact that all the big professional services firms in this town are run from elsewhere, I think is unfortunate. We’re quite proud that we have managed to build something professional here and do something substantial,” he says.

His own star has risen too. Tembel is in the upper echelons of Adelaide’s influencers. He is a confidant of senior politicians, including Premier Steven Marshall, who praised his “wealth of knowledge and experience” when appointing him last July as Productivity Commission chairman.

He also is well-regarded by Opposition Leader Peter Malinauskas, whose wife, Annabel West, is a partner in Thomson Geer’s corporate team. Tembel is a director of the Menzies Research Centre, a Canberra-based Liberal think tank, and the Hackett Foundation – a charity established by tech entrepreneur Simon Hackett and wife Anna.

Normandy Mining founder and former state Economic Development Board chairman Robert de Crespigny is a close friend and a

near-neighbour in their exclusive inner Adelaide suburb. Tembel lives among the upper middle classes whose homes he once admired – the family home was bought for $7m in 2016 – then setting a new record price for SA residential property.

The growth of Tembel’s career and the firm he leads defy a debilitating trend – the dramatic erosion of corporate Adelaide after the State Bank collapse – that galvanises Tembel’s role as South Australian Productivity Commission chairman (for which he doesn’t accept a fee).

The long-term historical figures the Productivity Commission produced are stark, alarming and debilitating for the entire state. Tembel stresses, though, that virtually all the data predates the Marshall government. “We focus on long-term trend data, so this is not about any particular government, this is about South Australia and its journey out of the State Bank disaster 30 years ago,” he says.

SA’s gross state product, which measures the state economy’s size, has been in decline relative to the rest of Australia since 1990/91.

SA’s growth has averaged 2.1 per cent since then, compared to the national average of 2.9 per cent. SA now represents 5.7 per cent of national output. If SA’s gross state product share had stayed at the 1990/91 level, the economy would be $29bn larger. That’s more than 10 times the $2.26bn announced on February 13 by Prime Minister Scott Morrison to complete the North-South Motorway. It’s about three times the total cost of the $9.9bn, 78km motorway.

But the GSP (gross state product) growth of 3.9 per cent in 20/21 was the nation’s highest. Have we finally turned the corner? Tembel is clear in his response: “Of course, it’s a great start following the external shock of the Covid recession and the previous decades of underperformance. Our job is to now maintain this performance with the best-possible economic management.”

It’s a long game; a stark 2020 Productivity Commission study found “growth in SA’s living standards came to a standstill, or flat spot, around the late 2000s”.

Some stark figures highlighting the challenges facing the state include:

SINCE 1990, SA’s average income has been persistently below that of NSW, Victoria and the national average.

FOR thesame period, SA had the second-lowest average living standards of any state or territory, above only Tasmania.

THE public sector has swollen since 2009-10, which equates to 6.4 per cent of government spending.

SA has the lowest national proportion of people aged 25 to 44 with a bachelor or postgraduate degree.

BUSINESS research and development spending has almost halved since 2008, leading to Tasmania overtaking SA for the first time.

THE state’s debt is projected to balloon to more than $33bn in 2024/25.

Productivity, Tembel explains, is measuring what someone is doing with their time and whether more is being produced over time. “Since the early 2000s, South Australian workers’ productivity has declined, while the rest of the world, including all the states, have gone up. It means we’re earning less and we’re continuing to earn less, because we’re just not improving and developing like the rest of the country. So we’re going backwards and we’ve become poorer than the rest of the country as we become smaller than the rest of the country.”

So how does South Australia turn this around?

“I use the word reform. “We have to continue to change and I think that change has begun with the Marshall government’s hi-tech and innovation agenda, but there is more to do. I am a huge believer that the state could allocate and prioritise more spending on research and development jobs – in other words, more people in laboratories, more well-paid scientists. If we could create more public sector jobs of that nature, we will do the right thing by our kids,” Tembel argues passionately.

“So, how do we do it? I think we should be very open to more change – not to cut government, but to redirect spending into even more productive activities. And that is so not easy. I’m not saying that insensitively, because change impacts on people’s lives.

“It’s no different to retraining factory workers who I watched being adversely impacted in the ’70s and their kids being affected. They were told, suddenly, ‘There is no job for you in the car factory. We’re going to retrain you and turn you into something else’.

“I’m not ignorant of that. We need to work hard and handle that transition, and maybe the federal government can help us along the way. But I think we have to face that reform opportunity. We all have to have the appetite for reform – employers, employees, public sector unions, and political leaders.”

These years of decline cannot be reversed by heaping pressure on political leaders for short-term fixes, Tembel argues, but by “a long-term reconstruction”. “I think our generation has to look at each other and say: ‘We have to do this over the next 20 years’,” he says.

“Old people like me need to play a role in helping the next generation and, in part, that is in ensuring kids get a better education. Then, when they’re out of school and university, they can maybe hook up with some entrepreneurial opportunities and do something major. A Lot Fourteen is very, very useful in creating the physical infrastructure. What I say we also need to prioritise now is human infrastructure, which is investing in the scientists, researchers and lab technicians who will generate the opportunities to create the next Google, Apple or major drug company.”

It’s an approach enthusiastically endorsed by Tembel’s mentor de Crespigny, a highly respected business identity who headed former Labor premier Mike Rann’s Economic Development Board from 2002 to 2006. De Crespigny says he has been “extremely impressed” by Tembel. “He’s a genuinely self-made person. He’s proud of his background but he doesn’t wear it on his sleeve, which I admire enormously,” de Crespigny says.

Describing their views on reviving SA’s economy as “very, very similar”, de Crespigny emphatically declares: “You should not pick winners and the job of government is to create an environment that encourages investment and entrepreneurship. We’re a state of small business. Picking winners, apart from being unfair, is not the way of small business.” The state, he says, has “massive net debt” and “the only way to come out of it, I think, is through development and discipline”. The governments that will change the state, he says, will have to deliver both.

Thomson Geer board member Brendon Cook, who in 1989 founded and then built Sydney-based oOH! media into a $1bn outdoor advertising giant, backs Tembel’s assessment.

“Having created a national business, one of the great challenges was finding talented people in Adelaide because the brain drain was enormous. I had many people who worked in our Sydney and Melbourne offices who had just got degrees in Adelaide and got in the car and driven out. I think South Australia doesn’t have a brain problem or a talent problem. It’s got to create the environment to keep professionals and executives coming back when they’ve got the skills or staying as they leave university because there’s opportunities for them to grow.”

This can be done, Cook says, by capitalising on the state’s attributes – talent, affordable housing, lifestyle to name a few – and creating “a future-led technology investment mindset”.

For Tembel, this future is the next wave of entrepreneurial business people. He says the decision announced on February 10 by global professional services firm PwC to create 2000 skilled jobs within five years at a Rundle Mall service hub demonstrates that Adelaide is becoming a destination for mid-level professional jobs. “It’s a wonderful story – just think about where the next wave of entrepreneur business person is going to come from. It’s going to be the young person at PwC, who is well-trained, smart and hungry. They connect up with a group of mathematicians at the University of Adelaide, or in a new research institute the state government might create. Then they come up with an idea and they’ve got the motivation and energy to take on the world,” he enthuses.

“It’s going to be a smart 25 year old, hopefully from a working-class area, who’s got a great university education and gets a skilled job at somewhere like PwC. Meanwhile, there’s some great engineer or mathematician who won a state government scholarship and did a PhD with his mates. That’s what kept him in Adelaide. They become friends at the pub. They hatch the idea. That’s what will take us to that national growth of 2.9 per cent and give us that extra $30bn. That’s our kids or maybe even our grandkids.”

It is an optimistic vision that will provoke scepticism and disbelief among some. But Tembel’s counter argument can always rest on his own life story – rising from a working-class migrant background to lead one of Australia’s top firms in the establishment profession of the law. A rise from adversity to prosperity – one that South Australians collectively can at least hope their state can emulate. ■