Inside the State Bank collapse of 1991 that crippled South Australia

FORMER premier John Bannon is being remembered as the man who brought the Grand Prix to Adelaide — but also for his role in the collapse of the State Bank. So what caused it? And who else was to blame?

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- ECONOMY: Is the State Bank collapse to blame for SA’s current state?

- MAIN REPORT: Stepson’s touching tribute to John Bannon

- SPEAKING OUT: ‘The best I could do was not good enough’

- FINAL DAYS: John Bannon’s last ‘superhuman effort’ for his father

- CASINO: The gamble that paid off

IN the summer of 1991, then premier John Bannon joined other South Australian powerbrokers at the launch of the fledgling Adelaide Crows at Football Park.

While the state’s first AFL team was about to hit the national stage, Mr Bannon was involved in a 13-day frenzy of secret meetings frantically trying to stave off a financial disaster that would wreck the state and trash his legacy as Labor’s longest-serving premier.

This was the State Bank collapse, publicly revealed on February 10, 1991, that a Royal Commission found lost $3.15 billion in government-guaranteed funds.

The scale of the disaster was just becoming apparent on January 29, when Mr Bannon and senior State Government officials were briefed at a private meeting by the bank’s board and top management. They were told about a J.P. Morgan report revealing the State Bank’s bad and doubtful debts could reach $2.5 billion.

The next day, January 30, Mr Bannon spent much of the day in a series of meetings with State Bank board members and Treasury officials. But, despite the gravity of the situation, the premier decided to maintain business as usual.

He kept his appointment at the Crows’ launch, then left for further meetings that night at his Prospect home.

Eleven days later, on Sunday, February 10, South Australians learned about the disaster for the first time, when Mr Bannon called a press conference designed to head off a run on the bank.

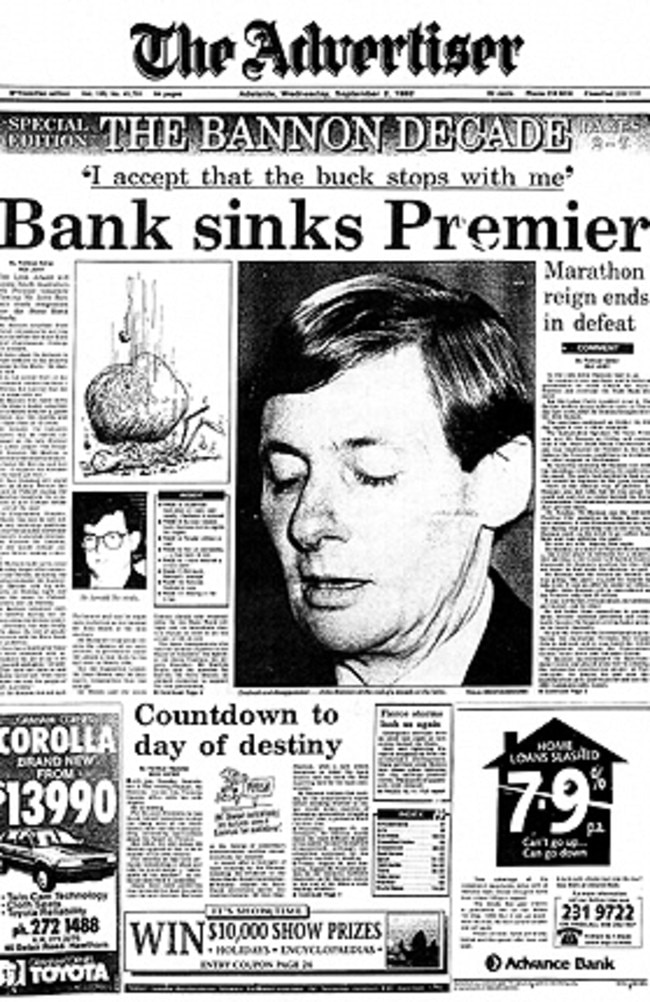

Taxpayers funded a $970 million lifeline and Mr Bannon, also the state treasurer, said he took full responsibility but would not take the “easy cop-out” of resigning, The Advertiser’s front-page story reported the next day.

The bank’s chief executive, Tim Marcus Clark, quit, as it was revealed the bank’s bad debts would cost the government $100 million a year to service.

The financial disaster shattered and angered the state, which arguably remains saddled with the impact of a decade spent trying to restore its finances.

Adelaide University political science Professor Greg McCarthy, whose 2002 book Things Fall Apart: A History of the State Bank of South Australia is the most recent in-depth analysis, charts management’s dangerous obsession with unrestrained and high-risk corporate lending.

Jory: The rare politician who cared little for self-interest

Penberthy: Bannon became a prisoner of the State Bank’s legacy

“The bank at its height had branches in London and New York and tax havens in the Cayman Islands, financing such ventures as the new (Rundle Mall) Myer complex, the renovation of (London’s) Wembley Stadium, mezzanine financing of apartments in New York, office blocks in Sydney and Melbourne, as well as holiday resorts on the Gold Coast,” Professor McCarthy writes.

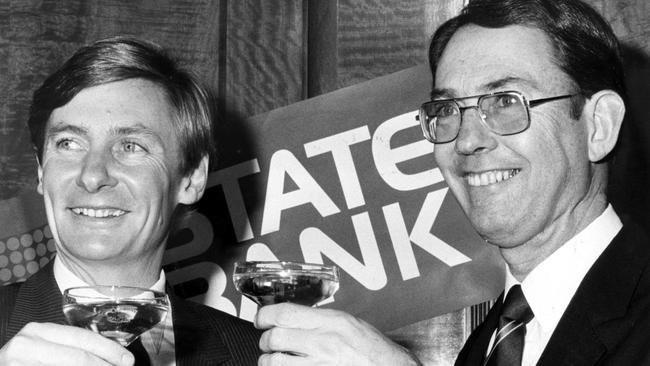

The State Bank of South Australia stemmed from a merger in 1984 with the Savings Bank of South Australia, with the now-infamous Marcus Clark as managing director.

The new bank, McCarthy says, was captured by a private sector entrepreneurial culture which destroyed public banking in SA. The merged banks had been renowned for their conservatism, lending to look after the rural sector and homeowners.

Marcus Clark “put a new broom” through the bank’s conservative retail culture and installed mostly men with limited banking experience — known as whiz kids within the bank. He promoted those loyal to his philosophy of “doing the deal”.

Beating competition to the deal was lauded, even if there was minimal security or promises against the sale of shares or property.

The loan-writing frenzy continued even after the 1987 stockmarket crash. In 1988, the bank grew by 39.5 per cent, its assets rising from $7.8 billion to $11 billion.

By 1990, the bank was dangerously overexposed to commercial property, in the mistaken belief this was safe.

In the final of three Royal Commission reports into the disaster, released in September, 1993, the then Mr John Mansfield, QC, found the losses were “largely the result of poor loans made to a vast spectrum of South Australian, national and overseas entities, through a variety of circumstances, not the least of which was the significant economic downturn in the national and international economy during 1989 and 1990”.

In the first Royal Commission report, retired Supreme Court judge Samuel Jacobs, QC, in November, 1992, said Mr Bannon, also the state treasurer, “failed to listen to the messages of doom” as the Bank headed toward disaster, branding his hands-off attitude “myopic”.

He says Mr Bannon was “dazzled” by Marcus Clark and a “plethora of signs of impending peril” in the 1989/90 financial year “failed to evoke an appropriate reaction” from Mr Bannon.

Mr Jacobs said the fact the Government guaranteed the bank’s business should, in itself, have prompted closer supervision of the bank’s activities. Mr Bannon told the commission he never considered the possibility the guarantee might be called upon.

“However, a new ocean liner does not put to sea without lifeboats because it is highly unlikely that they will be needed,” Mr Jacobs said, noting the “surprising failure of government” at an early stage “to assess and recognise its role and responsibilities as owner and guarantor”.

Sky News presenter and Australian and Sunday Mail columnist Chris Kenny — author of the 1993 book into the bank collapse State of Denial, says Mr Bannon was a clever politician and devoted South Australian who was clearly pained by what became of his premiership, yet remained determined to serve in other ways.

“We owe it to John Bannon, who was so dedicated to South Australia, not to rewrite history, cast him as a victim and fail to learn hard lessons,” Kenny told The Advertiser.

“The Bannon government’s high-risk creation, expansion and encouragement of the State Bank, Beneficial Finance and other entities such as SGIC, was a deliberate plan to claim the proceeds of capitalism for a Labor government and the state — it came unstuck badly because the financiers were effectively trading on their government guarantee.

“So Bannon was no victim — he failed badly and, along with Tim Marcus Clark and others, did the state enormous damage — yet it doesn’t eliminate the good things he did on Roxby Downs, the Grand Prix, defence industries, native vegetation retention and the like.”

Mr Bannon and other chief players in the State Bank disaster might have passed away, but the debate over the collapse that crippled a state will, doubtless, continue for years.

THE KEY PLAYERS

John Bannon: Premier and Treasurer 1982-92.

Royal Commission reports criticised him for failing to “listen to messages of doom” as State Bank headed toward disaster and a “myopic” hands-off attitude.

Tim Marcus Clark: State Bank managing director 1984-91.

Drove lax lending practices which triggered collapse, for which he has largely been blamed. Let down Mr Bannon by disguising or suppressing bad news and conveying only “euphoric views”. Went to extreme lengths to generate earnings.

HOW IT HAPPENED

JULY 1, 1984: State Bank formed, as a result of merger of old bank with the Savings Bank of South Australia.

FEBRUARY, 1989: After the collapse of Equiticorp, with debts to the bank of about $50 million, Opposition begins asking questions in Parliament.

JUNE, 1989: Bank reports “record” profit of $90 million, but $88.8 million is returned to the Government as dividend.

AUGUST, 1990: Bank reports before-tax loss of $400,000, only months after reporting to Government that it expected a surplus of $90 million.

DECEMBER, 1990: Mr Bannon says the bank chief, Tim Marcus Clark, and the bank, have his full confidence.

FEBRUARY, 1991: Mr Bannon reveals a $970 million bailout to cover expected

bank losses. He announces a royal commission. Mr Clark resigns.