Shady operator: How a German gardener you’ve never heard of saved Adelaide’s park lands

He’s the forgotten German immigrant who transformed Adelaide’s Park Lands a century ago and who has now inspired a new environmental prize. Roy Eccleston looks back at the life and times of Adelaide’s shadiest operator.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If you look hard, you will find his name on a small plaque on North Terrace – although you may need to brush away leaves from the elms and plane trees nearby. Not that August Wilhelm Pelzer would have minded the litter, because Adelaide’s most influential city gardener loved these tough, shady giants. He planted truckloads of them.

And not only elms and planes. Walk through Adelaide’s Park Lands today, stroll the city streets and into the nearby suburbs, cross the city squares – and you can thank this man you have never heard of. Perhaps, if you find a shady spot on a bench beneath a big old tree, it might be one of the many thousands he had planted.

Turn back the clock a century, and the man on this plaque was part way through 33 years of work to create a more beautiful, calming and healthy city through an ambitious program to transform the park lands – unplanned and often neglected.

Yet the memory of the talented German immigrant who was city gardener from 1899-1932 has largely been swept away like those leaves on North Terrace. The most significant nod to him is the impressive Pelzer Park (Pityarilly, Park 19) bounded by Greenhill and Glen Osmond roads.

But more should be done, says Pelzer fan Professor Chris Daniels of the University of Adelaide and UniSA, and chairman of the Green Adelaide Landscape Board, a new state body charged with making Adelaide a more climate-resilient city.

“And you can’t do that without trees,” Daniels says of the urgent need to reduce the impact of rising temperatures that will make parts of Adelaide a 50C city.

Today The Advertiser announces a prize in honour of Pelzer, as part of a campaign for Adelaide to become the second place in the world after London to be designated a National Park City. The Pelzer Prize will honour an individual or group making a lasting difference to the environment, leaving a legacy for future generations.

Without Pelzer, says Daniels, the park lands and city laid out by Colonel William Light would never have been so green. When he applied for the job in 1899, the park lands were still suffering from a mixture of exploitation, neglect and incompetence that had stripped it of many trees since settlement in 1836, he says.

By the time Pelzer left in 1932, aged 70, he had transformed its 800ha, connecting the whole with 30ha of formal gardens, playgrounds and avenues of trees in the city’s inner suburbs. He’d also planted thousands of trees (by 1912 he’d already installed 5000 trees and 10,000 shrubs).

In the process he helped excite Adelaide about the park lands, burnishing the garden city image – in his case, in a European “Gardenesque” style – we still boast about.

Today this green moat helps define Adelaide to the world – a venue for the Fringe and Womad, a backdrop to Test cricket, the soft blur behind televised car and bicycle races, and another reason for The Economist to this month declare the city the world’s third most liveable.

But more than that, says Daniels, the trees drop the temperature in summer by several degrees and warm the city in winter by the same amount. We all need to be inspired by what Pelzer did, he says, and act ourselves because once again we are removing trees for “progress”.

We have become a city of increasing sprawl, urban infill, smaller backyards, and fewer trees. “We’re certainly losing nature,” he says, lamenting how large inner urban blocks are being transformed with multiple homes.

“We are losing backyards. The inner suburbs are under enormous pressure. So we lose the tree canopy.”

That has come as we have changed our outlook, he says. In the past, the home needed a good-sized backyard because there had to be room for a game of cricket, a chook pen, a Hills hoist, a rainwater tank, a vegie garden and often some fruit trees.

ADELAIDE THEN

ADELAIDE NOW

“So we had this green space,” he says. “But it’s been disappearing for decades. People didn’t really think they needed backyards, they didn’t have time, they were spending more time indoors.”

The consequences of smaller backyards and fewer trees has been to make climate change much worse, particularly locally, he says. “If you remove the trees and you have a very large, hard surface, you’ve got more water run-off – so more discharge to the Gulf, more death of sea grasses, loss of fish, pollution.

“And hard surfaces heat up, so the city is hotter. We have to run more airconditioners, we wind up being really, really in trouble when you get these 40-50C days. We also have increased winds, because you’ve got the chimney effect created by really hard, hot surfaces.”

In other words, says Daniels, we need to heed the lessons of the mid-1800s when the Adelaide Plains had been stripped of much of its timber. He says that in the 30 years after the colony was established in 1836, much of the open woodlands were cleared for homes or agriculture, including the park lands and banks of the Torrens. The extent of the damage is shown in a 360 degree panorama of photographs taken from the top of the new Town Hall tower by Townsend Duryea in 1865.

“And when you look at it, you can see the devastated landscape of the Adelaide Plains,” Daniels says. “And it was useful in that Adelaide was very, very productive in terms of wheat, sheep and early market gardens and so forth. But it also was a horrible place to live, and by the 1880s, 1890s, people were growing tired of baking in the heat and flooding in the winter.”

The Torrens lost all its natural vegetation after settlement, and, not then dammed, could divide the city in a wide muddy flood in winter and slow to a narrow, shallow trickle in summer. As Patricia Sumerling notes in her book The Adelaide Park Lands – A Social History, there were limestone, sand and gravel quarries, rubbish dumps, grazing animals and brick works. It was a quagmire in winter and a tinderbox in summer.

“Adelaide was really struggling,” says Daniels. “So the city council felt they had to do something.” By 1880 the council had a plan to revive the park lands. The detailed work by the state’s conservator of forests, John Ednie Brown, sought to make the park lands more beautiful and usable. Brown preferred exotic species such as elm and plane, ash and oak and less eucalypts. He also wanted to divide the expanses into separate parks and recreation grounds, delineated by borders of trees with clumps of plantings within each area.

It was not implemented at the time. The city gardener then – like all those before Pelzer – was not properly trained and did not support Brown’s ideas. But public interest in tree cultivation was growing.

There were reportedly 80,000 trees in the park lands by 1884 and Arbor Day, copied from the US, started in 1889 to encourage schoolchildren to plant trees. Before then, Sir Thomas Edwin Smith, the city’s mayor twice in the 1880s, had set about beautifying the park lands himself, supporting the creation of what is now Elder Park, and preparing the ground – actual and political – for someone like Pelzer. Crucially, the mayor for much of Pelzer’s time, Sir Lewis Cohen, also supported the city’s beautification.

Pelzer was born in Bremen in 1862 (not 1864 as stated on the plaque, which also cuts short his career by one year). He joined his Lutheran relatives in Adelaide in 1886, applying his talents to gardens in wealthy suburbs like Unley Park. In 1899, he won the job of city gardener.

His job application, in beautiful flowing script and perfect English, is held in the council archives. “Dear Sir!” it opens enthusiastically, “referring to the advertisement re city-gardener, I beg to offer myself as a candidate for the position and I beg to state that I have a thorough knowledge of horticulture and especially of landscape gardening, having followed my profession for over 20 years.”

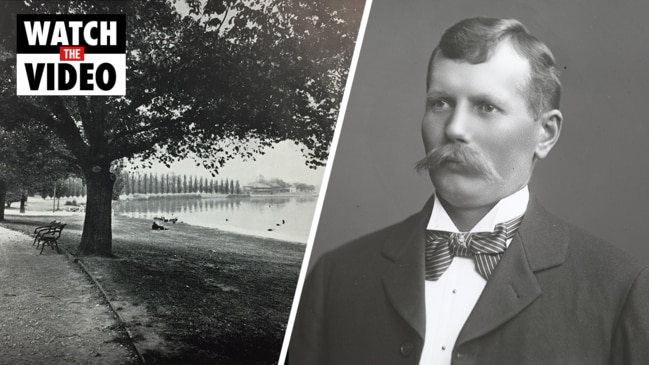

Pelzer was a coup. He had trained extensively in Germany and then London, where he had perfected his English and learned nursery techniques for growing stock of the kind he envisaged for Adelaide. A Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, he had also won prizes in SA. As historian Peter Morton writes in After Light: A History of the City of Adelaide & its Council 1878-1928, the 37 year-old Pelzer “was no country clodhopper”. Morton describes him as “a stern-featured, handsome man of military bearing”, but we really only have one photograph to go on, and little insight into his manner.

It is clear, though, that he was methodical, persistent, visionary and a very good communicator. He must have been personable and politically astute enough to forge strong and productive alliances with the councillors who supported him for more than three decades, including WWI when anti-German feeling was high.

From the start he realised he needed to make this his life’s project.

“We have a good 20 years’ work in front of us to bring the 2000 acres of parks under control up the standard of sightliness which the most favoured spots possess at present,” he told council in his first report in 1900. “It is a long time to look forward to, but good solid work is being accomplished each year.”

In for the long haul, Pelzer, who married Lucie Bothe in 1899, settled in a Federation villa in Rose Terrace, Wayville, and raised two children, Malcolm William and Largaretha (Greta) Lucie.

Landscape architecture and urban design expert David Jones believes Pelzer used Brown’s 1880 plan for much of his direction. Like Brown, he favoured exotic species. In a 2007 assessment for the city council on the cultural importance of the park lands, Jones wrote that Pelzer’s long tenure enabled a “visually coherent Gardenesque landscape to be designed, planted and created in the City including much of its roadside shelterbelts, that is underappreciated today”.

Initially Pelzer and his team of seven gardeners and 14 labourers focused on the city’s squares, which he lamented were being ruined by pedestrians. He invited council to run some roads through them – as with Victoria Square – the better to keep people off his newly planted grass.

“Since the tree-planting renaissance in 1899 it has not been possible with the labour at command to focus any sustained attention on the Park Lands,” he reported in 1900. “It has taken us all our time to attend to the public square, the gardens and the planting of the city’s roadways.

“In the future it may be possible to have a special staff for the Park Lands in order that they may be transformed from commons into beautiful recreation grounds as shown in the plans drawn by the late Mr Ednie Brown, which were specially prepared for the city council over a quarter of a century ago.”

Pelzer disliked natives trees, at least at the start. For streets he liked planes, golden ash and honey locust; for parks elm, white poplar, jacaranda, and Moreton Bay fig. Gums were “untidy, and unreliable, whereas some of the exotic trees had far more cooling impact, with broader and more dense canopies”, he wrote.

“In my opinion a tremendous mistake has been made in planting too many gum trees; the majority of trees about the park lands consist of gum trees, and most of them are decaying and dying. Gum trees about the plains of Adelaide will, in time to come, be trees of the past.

“The eucalypts will not submit to cultivation and civilisation, and it is my candid belief that with the progress of arboriculture gum trees will have to make room for Oriental, Mediterranean and South American species. The Australian climate is particular suitable for them, and they have come to stay.”

His set against gums upset some people; he wrote once that every time he stuck an axe into one, someone complained. But he mellowed: in 1915 he noted 140 wattles had been planted, and the following year recommended 500 gums go in.

By the 1920s there were seven gum species, 10 wattle species, as well as planes, palms, elms, white cedars, Norfolk Island pines and poplars in his Frome Rd nursery. He wanted them not only for new plantings, but replacing many trees that died in severe drought years when watering – by cart – could not keep up with need.

Pelzer saw his work as more than utilitarian. “A garden is a work of art, and every work of art should have a subject, theme, or motive,” he wrote.

“In certain types of gardening it may be possible to give a general – more or less vague – feeling of beauty, of festivity, or courtliness; but when one essays the larger flights of composition in formal landscape, it is positively necessary to artistic success that some definite, concrete motive be adopted and developed.”

He favoured the Gardenesque style, which emphasised the individual form of plants, displayed without obstruction by others, writes Jude Elton, of the History Trust of SA. “Plantings tended to be diverse and scattered rather than dense, with winding paths and island flower beds.” Morton adds that he grouped trees “so that fine vistas of the different parts of the park-land, of imposing buildings and of the surrounding Hills, may be obtained”.

His European approach won broad support. One admirer, Morton writes, likened Pelzer’s work to “an English nobleman’s estate”. Another ventured that someone seeing a panorama of Pelzer’s park lands “might have imagined themselves gazing on Parisian landscapes!”

The lands were certainly unrecognisable after he had finished. “Pelzer transformed the landscape into an extensive chain of gardens linked together by tree-lined streets,” Jones says in a 2006 paper on Pelzer’s role in the foundations of Adelaide’s “Gardenesque” parks and gardens.

“His major projects included extensive re-contouring and tree planting of the Adelaide Park Lands, the creation of Creswell, Pennington West, Pennington East, Angas, Kingston, South Terrace, Brougham, Palmer, Roberts Place and Prince Henry’s Gardens, Elder and the now Rymill Parks, the squares of Adelaide, most of the tree-lined residential streets of south and North Adelaide, and the landscape along North Terrace.”

Pelzer retired at 70, in 1932. Two years later he died of a heart attack after dinner. He was lauded by the council, in an obituary in The Advertiser, for his transformative work as one of the nation’s leading authorities on landscape gardening.

Daniels says Adelaide’s park lands continue to give the city a fine set of lungs but also remind us of the role of tree canopy in keeping us cooler. The mindset that produced them needs to be embraced again, to fight against climate change, he says.

The bushfires of early 2020 forced Australians to recognise the devastation climate change could wreak. “And then Covid changed the way we thought about how we should have our cities, if we’re forced to stay in the home for very long periods,” he says. “Nature, in terms of parks and streets and backyards, has become incredibly important.”

Adelaide must focus on urban infill and open space. “How are we planting up the streets? How are we using median strips and footpaths? Where are the remnant vegetation spots that we preserve?” Daniels says.

“It’s a no-brainer, really – trees are the way out of our dilemma. We can make a greener, more climate resilient city – and you can’t do that without trees.”

Pelzer, were he here today, would surely have agreed.

Do you know an champion of the SA environment? Nominate them for a Pelzer Prize today.